1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

6, 7, 8, 9,

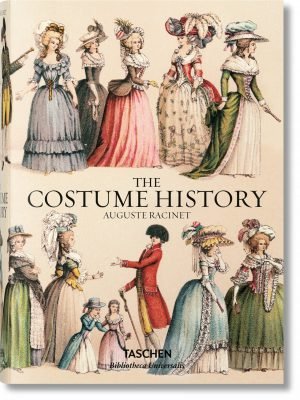

The Hoop skirt, the Panniers, the Justaucorps.

Around 1710, the men’s skirt appears with bell-shaped puffed up lapels (à pans bouillonés), which were modelled on the female costume. The latter was closer to the waist than had previously been the case and was stiffened from the hips downwards by whalebones. It also became lighter, narrower and shorter. In order to make the parts of the lap bulgy, five or six round folds were made on the sides, starting from a button sewn to the hips, which widened downwards, thus strongly accentuating the curve of the waist.

Around 1719 the folds were stiffened by paper or horsehair inlays. Later the pleats were moved to the back of the lap to the right and left of the slit. The luxury dress, consisting of the men’s frock (justaucorps), the waistcoat and the leg dresses, whereby three pieces of wealth or simplicity harmonized with each other, caused extremely considerable expenditure, since certain distinguished gentlemen regarded the daily change of clothes as a matter of etiquette.

Suit No. 7 is the gala dress of a Knight of the White Eagle, whose Order was founded by August II, King of Poland, in 1705. The order is embroidered in coloured silk with the motto “pro fide, rege et lege” (Loyalty to King and Law). The coat has cuffs on the chest and sleeves, which are provided with buttons and buttonholes. On the left side of the lap there is an opening to put the dagger through, as you can see at no. 4. The vest, whose sleeves have no cuffs, rises up to the neck. The buttons and buttonholes do not go down to the bottom, as can be seen in the other skirts. The leg dress was fastened under the stocking and has neither buckle nor trouser band. The dress is in the historical museum of Dresden.

The bourgeois classes dressed in cloth, ratiné (roughened wool fabric) and coarse Camelot. Depending on the season, full- or half-wool fabrics were chosen. Almost always the skirt, waistcoat and trousers were of the same or similar colour, with nuances ranging from dark red to light brown. Black did not begin to become the colour of the ceremonial dress until around 1750. Nos. 3 and 4 are the oldest of our table. The skirt is very wide and the lapels are not bulged. Nos. 6, 8 and 9 are from the period 1730-1740, No. 8 with closed and belted waistcoat, with leather gaiters in the style of cavalrymen (dragoons) and spurs, wears travelling clothes. The stockings kept so little warm in those days that in very cold weather it was necessary to put on several pairs over each other. In 1729, when the winter was extremely severe, leather riding boots were also worn in the city.

At nos. 3 and 9, the waistcoat can be seen open to the stomach area, so that the herade and the long falling ends of the linon or muslin cravat are visible. The jabot with its frolicsome folds was not yet common at that time. One used to carry the hat, to protect the wig, in the hand or under the arm. The citizens wore stockings of black, grey or mottled wool according to the old fashion, which prevailed until 1730, i.e. the stockings went as far over the trousers as the riding boot would reach. Nos. 6, 8 and 9 are taken from engravings by Leclerq, who began to try out the talent in them that he later developed in the Galerie des modes et costumes française.

Nos. 1, 2 and 5 represent women with paniers. The origin of these skirts, which imitate the shape of a chicken basket, is dark. According to some, this fashion came to France from England, according to others from Germany; a third view traces its origin back to the stage. The heroines of tragedy, who clung to the bulges from the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century, had always given their skirts a wide girth by artificial methods. In 1711, hoop skirts, the hoop petticoat, could be seen on the streets of London, and English journalists poured the flood of their mockery on this fashion.

In France it spread from 1718 through two English ladies who appeared in the Tuileries wearing such skirts. Those on our table belong to the first period of this fashion. The depicted skirts are not the large dresses, falling down like a wide dressing gown, folded at the back like an abbé coat, which were the usual ladies’ dress of the 18th century. The robe with its long, tightly fitting waist still retains the stiffness sought after at the beginning of the century. It was only gradually, from the first years of Louis XV’s reign, that women began to wear the loose, negligee-like dress that was one of the greatest attractions of the female costume.

The panier was in fashion until the last years of kingship. Even old women could not part with this fashion, as can be seen in the book by Jules and Edmond de Goncourt La Femme au XVIIIe siècle (1882), which speaks of the death of a hundred-year-old old woman caused by the fitting of a panier. In 1765, only half paniers (demi-paniers), also called jansénistes, were still visible.

Under Marie Antoinette, they once again took on an immense size in court costumes, but without reaching the former conditions which had made it necessary for the princesses to have an empty tabouret (stool) beside them. There were paniers à l’anglaise, à la française, à l’espagnole, à l’italienne, in all sizes and shapes, up to the small morning paniers called considérations. They were inseparable from all the city toilets, even the simplest negligee, called casaquin or pet-eun-l’air, where the laps fell on the panier.

The panier was constructed on the pattern of chicken baskets from hoops of whalebone, rushes or light wood, which were attached to each other with bands or twisted yarn. After 1725, this construction was covered with unbleached canvas, coarse taffeta or even knitted silk, thus becoming a real skirt, replacing the skirts that were common in the past. The paniers became commonplace in all classes of society ever since Mlle Margot had found the way to supply paniers at a cheap price, regardless of their princely size, by simply sewing whalebone hoops onto a canvas that formed the petticoat.

Although the Church initially took offence at this fashion, considering the banner as an encouragement to debauchery because it was capable of concealing the consequences of the same, it eventually had to let the fashion prevail. The same was extremely uncomfortable in the theatre, in the salons, on walks and especially in the carriage – two paniers filled the coach.

Nevertheless it was still in its full bloom in 1745. In that year, as the lawyer Barber testified, no woman would have dared to emancipate herself from the same. One did not fear the indiscretions that the same one had in her wake, although wearing trousers was considered a sign of loose morals in those days. In the encyclopedia of 1765 one reads: “This fashion is in decline; today one goes to the street and the theatre without a panier; one no longer wears it on stage either.” But this reform was not long in coming.

No. 2, which still carries the long falling throw (volant en queue), is the oldest of our three women’s costumes. The panier, which has the shape of an upturned funnel, is the first stage in the development of the stiffened skirt, the criarde, which it replaced. Number 1, whose upper skirt part is rounded, is called Panier à Guéridon, number 2 Panier à la Coupole. But soon one came to the Panier à Coudes (No. 5), which was called so because it had assumed such a width at the sides that one could support the elbows on it. This panier had five hoops above each other, the top of which was called Traquenard.

After dropping the fontange, one fell into the opposite, making the head quite low. The hair was only slightly coiffed and only reached up to the temples at the sides. A light lace bonnet with fluttering ribbons was worn, which was attached with needles. This headdress was preserved until 1760, when people wore small shoes with 3-4 inch high wooden heels that were advanced to the integration of the sole. The falbel skirts, the heavy brocade fabrics with large arabesques had to be abandoned, as skirts had to be worn, for which 10-12 cubits of fabric were needed. The heaviest fabric was silk with a large leaf and twig pattern. For the summer one chose light silk, Indian cotton, muslin, gauze or a twill fabric made of linen and cotton (basin).

The inclination of the century for the country life, which at that time was only at its beginning, was nevertheless already noticeable in the character of No. 5. The wide-brimmed straw hat with a flat head, the bouquets of flowers painted on the dress and the apron, which was brought out again with great success, all point to the rural taste. The apron was, however, in contrast to the custom of ladies at the end of the 17th century, worn without bib, which now became the distinguishing sign for the aprons of chambermaids. The stiffness of the open bodice was still reminiscent of the old Gourgandine; the neckline remains the same.

Before the coat or flounce that fell from the pieces at the back of the skirt was completely suppressed and the bodice with laps and the casaquin became out of it, the flounce was worn, as number one shows, gathered into a package at the back. In the front neckline of the bodice there were still ribbons and loops attached above each other like the rungs of a ladder. In winter, people wore the palatine, a collar made of marten fur or grey work, in summer blondes, coloured ribbons, chenille or serrated taffeta stripes around the neck (No. 5). Fashion thus presents itself as a compromise between the last times of Louis XIV and the first of the regency.

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.