The “Hardwick Hall” portrait of Elizabeth I of England circa 1599 by the Workshop of Nicholas Hilliard

A cyclopedia of costume. Dictionary of dress.

ABACOT, ABOCOCKE, ABOCOCKED, ABOCOCKET, BYCOCKET.

(French, bicoquc.)

A cap worn during the fourteenth, fifteenth, and commencement of the sixteenth century by royal and noble personages.

Spelman has, “Abacot, Pileus augustalis Regum Anglorum duabus coroniis insignatus. Vide Chronica, ann. 1463, Edw. IV. pag. 666, col. ii. lib. 27.” He has been followed literally by Ducange, and without further explanation by the recent editors of the latter. Abacot is also inserted in Bailey’s and other English dictionaries, the former erroneously describing it as “a royal cap of state made in the shape of two crowns, anciently worn by the kings of England.” Insignatus signifies ensigned or distinguished, and in Hall’s Chronicle we find the cap mentioned thus: “King Henry was this day the beste horseman of his company, for he fled so faste that no man could overtake hym, and he was so nere pursued that certain of his henxmen or followers were taken, their horses being trapped in blew velvet, whereof one of them had on his hed the said Kyng Henries healmet, some say his high cap of state, called Abococked, garnished with two riche crownes, which was presented to Kyng Edward at Yorke the fourth daie of May.” (Union, sub reg. Edward IV. f. 2.)

Grafton and Holinshed have the same account, but the former spells the word Abococket, and the latter Abacot and Abococke. At the coronation of Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV. and queen of Henry VII., A.D. 1487, we read that “the Earl of Derby, Constable of England, entered Westminster Hall, mounted on a courser richly trapped and enamed-that is to say, quarterly golde, in the first quarter a lion gowles, having a man’s hede in a bycocket of silver, and in the ijde a lyon of sable. This trapper was right curiously wrought with the needell, for the mannes visage in the bycockett shewed veryly well favoured.” (Leland’s’ Collectanea,’ vol. iv. p. 225.)

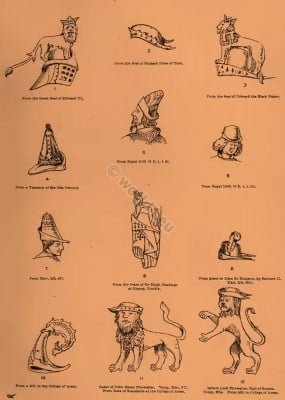

Why the trappings of the Earl of Derby’s horse should have been emblazoned with these charges or badges, was a question difficult to answer; such a device as a lion with a man’s head in a bycocket not appearing to have been borne by the Stanleys. It is to be seen, however, in the standard of John Ratcliff, Baron Fitzwalter (Book of Standards, Coll. Arms; vide Plate I. fig. II); and on referring to the notice of that nobleman in Dugdale, we find that on the 3rd of Henry VII. he was associated with Jasper, Duke of Bedford, and others, for exercising the office of High Steward of England at the coronation of the said Queen Elizabeth. It is therefore clear that it was Lord Fitzwalter as High Steward, and not the Earl of Derby as Constable, who rode the courser so “trapped and enamed.”

That the abacock or bycocket was not peculiarly “a royal cap of state” appears from an entry in a MS. of the close of the fifteenth century, in the College of Arms, marked L. 8, fol. 54b, entitled ‘The Apparel for the Field of a Baron in his Sovereign’s Company.’ “Item, another pe. of hostynge harness [to] ryde daily with all, with a bycocket and alle other apparell longing thereto.”

It is, I think, evident that the abocock or bycocket was the cap so frequently seen in illuminations of the fifteenth century, turned up behind, coming to a peak in front, varying and gradually decreasing in height, encircled with a crown when worn by regal personages (vide Plate 1. fig. 4), and similar to, if not identical with, what is now called the knight’s chapeau, first appearing in the reign of Edward III., and on which the crest is placed (Plate I. figs. I, 3, and 8); as we may fairly conclude from the badge of Robert Fitzwalter (One of the twenty-five sureties of Magna Carta), Earl of Sussex (temp. Queen Elizabeth), the descendant of John, Lord Fitzwalter, before mentioned, in which it is depicted with the two peaks worn behind as in achievements of the present day. (MS. College of Arms, Vincent, No. 172. Vide Plate I. fig. 12.)

In the list of articles ordered for the coronation of Richard III. “two hats of estate” are directed to be prepared, and worn “with the round rolls behind and the beeks before:” (Book of Piers Courtenay, the King’s Wardrober.) As these hats were provided for the two persons representing the Dukes of Normandy and Aquitaine, I take it that they were ordered to be so worn in accordance with some ancient fashion, as at this period and subsequently the knight’s chapeau is always represented with the peaks or beaks behind. The two crowns that are said to have garnished the cap of Henry VI. might have betokened the kingdoms of France and England. M. Viollet le Duc, on the authority of an anonymous writer, gives examples of a closed helmet as a bicocquet. That it was not a helmet is perfectly clear from the contemporary documents I have quoted, with which M. VioJlet Ie Due was evidently not acquainted. The name, however, might have been capriciously applied to a steel head-piece, as it is at the present day to small dwelling-houses.

ACTON, AKETON, HACKETON.

(French, aqueton, auction, hoqueton.)

A tunic or cassock made of buckram or buckskin, stuffed with cotton, and sometimes covered with silk and quilted with gold thread, worn under the hauberk or coat-of-mail, used occasionally as a defensive military garment without the hauberk.

In a wardrobe account, dated 1212, twelve pence is entered as the price of a pound of cotton required for stuffing an aketon belonging to King John. (Harleian M/S. 4573·)

Chaucer, describing the dress of a knight, says:

“Next his sherte a haketon,

And over that a habergeon

For peircing of his heart,

And over that a fine hauberk

Was all ywrought of Jewe’s work.

Full strong it was of plate.”

Rhyme of Sir Topas.

This passage has been a sad puzzle to commentators, but it is curiously illustrated by a miniature in a fine copy of Boccaccio’s ‘ Livre des nobles Femmes’ in the Royal Library, Paris. (See under HAUBERGEON.)

That the colour of the aketon was generally white appears from the old French proverb, “Plus blanc qu’un auketon.” “But this was not invariably the case,” remarks Sir S. R. Meyrick,”“for Matthew de Couci in his’ History of Charles VII.’ says, ‘ Portoient auctons rouges recoupez dessous sans croix.'” (Archæologia, vol. xix.); and in the ‘Romance of Sir Carline’ we have, “His acton it was all of black.” (Halliwell’s’ Dictionary of Archaic Words,’ in voce.) I infer, therefore, it was usually coloured when intended to be worn, as in these instances, without or in lieu of the hauberk. In an inventory of John Fitz Marmaduke, Lord of Horden, we find mention of an aketon covered with green samite, and a red aketon with sleeves of whalebone, “cum manicis de balyn.” (Vide Glossary to Meyrick’s ‘Critical Inquiry’ under” Gaynepayne,” vol. iii. 2nd ed.) Camden describes it, however, as “a jacket without sleeves, called a haketon.” (Remaines, p. 196, ed. 1657.) In process of time the word was applied to a defence of plate. In a letter of the year 1478, quoted by Sir S. R. Meyrick, we read of a silver aketon, “Lequel Perrin bailla à celui mace ung coup de la fourche en la poitrine, dont il le navra, et l’eust tué n’eust este son hauqueton d’argent.” (Archælogia, ut supra.) And a writer of the reign of Elizabeth says, “Haketon is a sleeveless jacket of plate for the warre covered with any other stuffe; at this day also called a jacket of plate.” (Animadversions on Chaucer, by Francis Thynne, 1598. His note is only valuable as an authority for his own time.) The “haketon” of Chaucer was not of plate. M. le Duc actually represents the heraldic tabard as a hoqueton!

The etymology of the word is much disputed. Sir S. R. Meyrick derives the French word hoqueton from the German hauen, to hew, and Quittung, a quittance. “Hence,” he observes, “it would imply an obstacle to wounds.” This, I think, is rather far-fetched. After all, it may be simply a corruption of the French à cotton or au cotton the material with which the garment was stuffed, or of the original Arabic word alkoton, from which the ‘Italians derived their cotone, the French cotton, the English “cotton,” and the Spaniards, retaining the article, algodon. The “auqueton qui d’or fu pointurez” is well displayed in the figure on p. 2, from Royal MS. xiv. E. 5, where a knight is depicted as being wounded while he is putting on or taking off the hauberk which was worn over it.

AGGRAPES.

(French, agrafe)

A clasp or buckle. Also, hooks and eyes.

AGLET, ANGLET, AIGLET, AIGUILLETTE.

(French, aiguillette.)

The metal tag to a lace, or point, as it was called; sometimes used to signify the lace or point itself, as in the military costume of the present day. Also the ornament of a cap or bonnet of the sixteenth century.

“A doblet of white tylsent cut upon cloth of gold embraudered, with hose to the same and clasps and anglets of golde, delivered to the Duke of Buckingham.” (Harleian MS. No. 2284: Wardrobe Inventory, 8th Henry VIII. 1517.) “Item, a millen bonnet dressed with agletts, I IS.” (Roll of Provisions for the Marriage of the daughter of Sir John Nevil, temp. Henry VIII.: Archæol. vol. xxvii. p. 87.) “Aglet of a lace or point fer.” (Palsgrave,’Eclaircissements.’) “Aglet, Aygulet: a little plate of any metal was called an aglet.”-Halliwell in voce. “A spangle: the gold or silver tinsel ornamenting the dress of a showman or rope dancer.” (Hartshorne, Salop. Antiq., p. 300.)

Aygulet “Which all above besprinkled was throughout

With golden aygulets that glistend bright.” Spenser’s Faery Quem, ii. 3, 16.

Aglottes. “Two dozen poyntys of cheverelle

The aglottes of sylver fyne.” Council of the Jews – Coventry Mysteries, p. 241•

The aglets or tags were sometimes cut into the shape of little images, whence the term “agletbaby” is applied to a very diminutive person by Shakespeare: ‘Taming of the Shrew,’ act i. s. 2.

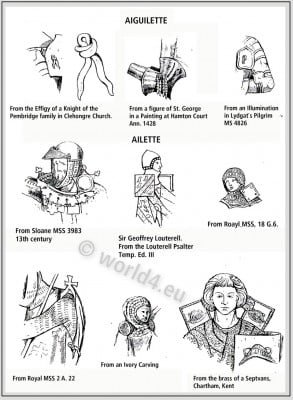

Aiguillette. A lace, strap, thong, or point, used during the Middle Ages for fastening pieces of plate armour, and also for connecting various portions of the civil dress, such as sleeves, hose, doublets, &c. “Pour six livres de soye de plusieurs couleurs pour faire les tissus et aiguillettes ausdits harnois.” (Account of Etienne de la Fontaine, Argentier du Roi, fait en 1352.) “Item. Store of dozen of armynge poyntes, sum w’. gylt naighletts,” i.e. aglets or tags. (The Apparel for the Field, MS. Coll. Arms, L. 8, p. 86b.)

In the ‘History of Charles VI.,’ by Jean le Fevre, Seigneur de St. Remy, the English men-at-arms are described preparing for the battle of Agincourt by replacing their “aiguillettes”; and in a note on that passage by Sir S. R. Meyrick, he says, ” In the time of Henry V. the fronts of the shoulders, a wound received in which renders a man hors de combat, were protected by circular plates called ‘palettes,’ and these were attached by straps or points as they were called, with tags or aiguillettes at the end. The word here implies the whole fastening. The elbows were sometimes similarly protected. An illumination in Lydgate’s ‘Pilgrim’ (Harleian MS., Brit Mus., No. 4826) exhibits the Earl of Salisbury with palettes in which the aiguillettes are very conspicuous.” (Nicolas, ‘Hist, of the Battle of Agincourt,’ notes, p. 114. See Plate II. fig. 4 of this work for the example alluded to, and fig. 3 for a specimen of the fastening of the elbow-pieces, from a curious painting of the fifteenth century at Hampton Court ; see also under AlLETTES.) The accompanying woodcut, from a print, 1650, exhibits their application in the civil costume of that period. The term aiguillette is also applied to a shoulder-knot worn during the last two centuries by soldiers and livery servants. In the English army an aiguillette is the distinction of field-marshals, aides-de-camp to the sovereign, and the officers of the Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards, Blue. It is of gold and worn on the right shoulder under the epauietta Non-commissioned officers of the Household Brigade of Cavalry wear an aiguillette on the left shoulder, not by regulation order, but by permission of Gold Stick.

AILETTES, ALETES.

(French, ailettes.)

Defensive ornaments of various shapes and materials, worn by armed knights on their shoulders (whence their names, ailettes, little wings), and introduced towards the close of the thirteenth century. They continued in fashion till about the middle of the reign of Edward III. They were generally emblazoned with the armorial bearings of the wearer, or simply with the cross of St. George, and therefore sometimes called gonfanons, from their resemblance to a small flag or banner. They are to be seen square, round, pentagonal, and shield shaped, and in one instance they appear as small crosses patée.

Their use appears to have been the protection of the neck, like the later pass-guard; and in the specimens presented to us in paintings and sculptures, “We see them,” remarks Sir S. R. Meyrick, “placed sometimes in front of the shoulders, sometimes behind, and others on the sides; whether, therefore, they were fixed in these positions or made to traverse I cannot pretend to determine, though from one appearing in front while the other is worn behind, in the pair worn by the knight in the ‘Liber Astronomire,’ a MS. in the Sloane Library, marked No. 3983, I am inclined to the latter opinion. (Archæeologia, vol. xix.) ” Autre divers garnementz des armes le dit pieres avesc les alettes garniz et freitez de perles.”- (Inventory of the effects of Piers de Gaveston, taken A.D. 1313: Rymer’s Fcedera, vol. ii. p. 31.) “iii paire de Alettes des armes le Comte de Hereford.” (Inventory of the Effects of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, A.D. 1319 : Duchy of Lancaster Office.)

In a roll of purchases made for a tournament at Windsor, 6th of Edward 1., A.D. 1278, we find “I. par Alett,” and ” XXXVIII. par Alettañ” (Archæeologia, vol. xvii. p.217.)

These were formed of leather lined and covered with cloth, called carda, and attached to the shoulders by laces of silk. Mr. T. H. Turner, who alludes to this in the eighth number of the ‘Archæeological Journal of the Institute,’ seems to have overlooked the fact that the whole of the armour for this tournament was made of gilt leather, being a mere May game, and, therefore, no authority for the ailettes worn with real armor. It is unfortunate that the Inventory of the Earl of Hereford’s effects, quoted above, has not supplied us with the desired information. While left to conjecture, it appears to me most probable that the ailettes worn in battle were made either of steel plates, the intermixture of which with mail was then commencing, or of cuir bouilli, that celebrated preparation of leather so variously used in the composition of defensive armor. An effigy of one of the Pembridge family, in Clehongre Church, Herefordshire, presents us with ailettes fastened by arming points. The means by which they were generally affixed to the shoulders cannot be ascertained from the other examples.

ALAMODE.

(French, à la mode.)

A silk resembling lutestring, mentioned in the fourth year of the reign of Philip and Mary. (Act for the Better Encouragement of the Silk Trade in England. Ruffhead, vol. ii. p. 567.)

ALBE, AWBE.

(Latin, alba)

A shirt or white linen garment reaching to the heels (whence its names, alba, telaris, &c.), and folded round the loins by a girdle, formerly the common dress of the Roman Catholic clergy ; but now used only in sacred functions. The second vestment put on by the priest when preparing for the celebration of mass. The choristers were called ” albae infantes,” from their wearing this dress, ” quorum vestes propriae alba est.” (Ducange in voce.)

“The Albe,” says Mr. Pugin, “is the origin of all surplices, and even rochets, as worn by the bishops, the use of which is by no means so ancient as that of the former.” It was sometimes richly embroidered, and even jewelled round the bottom edge and the wrists, from the tenth to the sixteenth century. Another mode of decoration is observed, consisting of oblong or quadrangular pieces of embroidery, varying from twenty inches by nine to nine inches by six from the bottom of the Albe, and from six inches by four to three inches for the wrist. These pieces were called the “apparel ” or ” parure ” of the albe, and were taken off when it required washing. “For washing of awbe and amyce partying [appertaining] to the vestments of the garters and flour de lice, and in sewing on the parells of the same, (St. Peter’s Sandwich: St. Boy’s Collection,’ p. 364.) The albe used by St. Thomas à Becket, when an exile from England, is still preserved, with his mitre and other portions of his episcopal robes, in the cathedral church of Sens. It is ornamented with purple and gold apparels of a quadrangular form.

In the English Church albes of various colours were introduced, although the vestment still retained its original name. Silk albes were also worn in the Middle Ages. In Gunton’s ‘ History of the Church of St. John the Baptist, Peterborough,’ there is a list of albes in which mention is made of twenty-seven red albes for Passion Week, forty blue albes of different sorts, fourteen green albes with counterfeit cloth of gold, four albes called “yerial white,” seven albes called “yerial black.“ Mr. Pugin observes, “This is the most curious list of albes I have met with, and is one of the many proofs of coloured albes in the English Church, but I have not found any document which mentions the practice on the Continent.” (Glossary of Ecclesiastical Costume and Ornament, p. 3.) In Picart’s Cérémonies Religeuses,’ Vol.II plate of the ‘ Processions des Rameaux,’ the clergy are represented in apparelled albes and the acolytes in plain; and in his ‘ Procession of the Fete Dieu ‘ is shown the fashion introduced about that period, 1723, of edging the albe with narrow lace. (Vide Pugin, ut supra, for an elaborate article on the albe; Ducange in Alba, Alba parata, &c.

ALCATO.

A collar or gorget, mentioned by Matthew Paris as worn by the Crusaders in the thirteenth century.

ALLECRET, HALECRET, HALLECRET.

A name given to a particular sort of plate armour worn by the French light cavalry and the German and Swiss infantry, circa 1535. Sir S. R. Meyrick says the term signified ” all strength,” and he applies it to a particular breast and backplate in the armoury at Goodrich Court with the Nuremberg stamp on it, and engraved in Skelton’s

‘ Illustrations,’ vol. i. p. xxv. For this opinion there is, however, no foundation, and it is apparently contradicted by the allusions to it in contemporary documents. Pere Daniel gives a different description of it : ” Le halecret étoit une espèce de corselet de deux pièces, une devant et une derrière. II étoit plus leger que la cuirasse.” And in the ‘ Ordonnances’ of Francis I., the French chevaux legers are required to be “armez de hausecou, de hallecret avec les tassettes jusque au dessous du genoul,” &c. (Histoire de la Milice Francoise, tome v. p. 397, ed. 1721 ; Guillaume de Bellay, Discipline Militaire, liv. i. f. 29.).

I consider Daniel’s description to be most correct, and that it was a species of gorget with a back-piece deriving its name from the German word ” Hals,” the neck or throat, which it specially protected. Mr. Hewitt (‘ Ancient Armour and Weapons in Europe,’ vol. iii. p. 599) simply calls it a corslet without further observation. Demmin, ‘ History of Arms and Armour,’ calls it decidedly a gorget, but gives also Halberkrebs as the German name for the lower part of plate armour with the long cuisses of the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth century, which appears to answer to the ” Hallecret avec les tassettes jusque au dessous du genoul” of the time of Francis I. “Hallecret” is suspiciously like a French corruption of ” Halberkrebs.”

ALLEJAH.

In an advertisement of clothes for sale in 1712 appears, amongst other articles of ladies’ dress, an ” Allejah petticoat, striped with green, gold, and white.” No conjecture can be indulged in as to the origin of the name, which, as I have not met with it in any other document, may be a typographical error. Another unexplained name is given in the same advertisement to both gowns and petticoats of very costly materials.

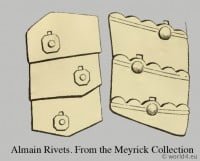

ALMAIN RIVETS.

Sliding or movable rivets, invented about the middle of the fifteenth century by the Germans, and giving their name to the complete suits of armour, ” so called because they be rivetted or buckled after the old Alman fashion.” (Minshew.)

Grose quotes an indenture between Master Thomas Wooley and John Dance, Gent, in the fourth year of Henry VIII., on the one part, and Guido Portavarii, merchant of Florence, on the other part, whereby he covenants to furnish two thousand complete harnesses, ” called Alemain Rivetts, accounting always among them a salet, a gorget, a breastplate, a back-plate, and a payre of splints, for every complete harness.” (Military Antiquities, vol. ii. p. 51.)

“Almane belett” evidently a mistake of the copyist or the printer, is mentioned as armour in an account of Norham Castle, temp. Henry VIII. (Archaeologia, vol. xvii. p. 204.)

Almond (for Almaine) rivett. In an inventory taken in 1603, at Hargrave Hall, Suffolk: “Item, one odd back for an almond rievett.

AMESS, AMMIS, AUMUSES.

(Latin, almecia, alimiciitm ; German, Mutze, a cap; old French, musser ; Provencal and Catal., almuser: Ducange, edit. 1840.)

A canonical vestment lined with fur, that served to cover the head and shoulders, perfectly distinct from the amice. (Way, in Prompt. Parv.) Also a cowl or capuchon worn by the laity of both sexes. ” Ammys for a Channon, Aumusse.” (Palsgrave.) ” Grey fur was generally used.” (Halliwell.)

” Those words his grace did say

Of an ammus gray.” Skelton’s Works, vol. xi. p. 84.

So also Milton has : ” Morning fair Came forth with pilgrim steps in amice grey.” Paradise Regained, book iv. line 426.

It was worn by the monks ” ut almutiis de panno nigro vel pelibus caputiorum loco uterentur ” (Clemens V. P. P. in Concilio Viennensi statuit) and formed a portion of the Royal, Imperial,and Pontifical habit.

“Or issirent-ils de Paris et encontra le Roy, l’Empereur son oncle assez pres de la Chapelle. A leur assemblée l’Empereur osta I’aumusse et chaperon tout juz.“ (Chron.Hand.,cap.103.) ” Ubi Imperator sedens deposita almucia” (Ceremon. Romanum, lib. i. sec. 5.) ” Pour 24 dos de Gris a fourrer aumuces pour le Roy” (Comptes d’Etienne de la Fontaine, Argentier du Roi. Anno 1351. Cap des Pennes.) Little aumuses, almucelles, are mentioned in the will of Ramirez, King of Aragon, A.D. 1099.

The aumuse was likewise worn by females, as in the accounts of Etienne de la Fontaine before quoted there is the entry following: ” Pour fourrer une bracerole et une aumuse pour la dite Madame Ysabel.” In Bonnard’s ‘ Collection of Costumes,’ Pope Sixtus IV. is represented wearing a scarlet ” aumusse doublee de hermines que les Papes portent encore de nos jours.” (Plate I. vol. i. p. 10.) Plate 83 in the same volume presents us with a canon wearing the Aumuse, from an effigy of the date 1368. It is of black cloth, lined with fur, and so coloured on the authority of Père Bonami, corresponding with the ” almutiis de panno nigro,” mentioned above. (See wood-cut). Though peculiarly a canonical vest- ment, it is evident therefore from the above quotations that it was worn by both sexes and all classes.

Mr. Pugin defines it as ” a hood of fur worn by canons, intended as a defence against the cold whilst reciting the divine office,” and adds, ” it is found in brasses, the points coming down in front, something like a stole. In this respect it was worn somewhat differently from the present mode of wearing it on the Continent. The usual colour was grey; but for the cathedral chapter, white ermine; in some few cases, where the bishop was a temporal prince, spotted, the tails of the ermine being sewn round the edge.” (Glossary of Ecclesiastical Costume.)

I believe the points that are seen hanging in front, like a stole, are portions of a distinct article of attire, called the tippet, and worn under the aumuse.

AMICE, AMYCE, AMYTE.

(Latin, amictus.)

The first of the sacerdotal vestments. “Primum ex sex indumentis Episcopo et Presbyteris communibus sunt autem illa Amictus, Alba, Cingulum, Stola, Manipulus, et Planeta.” (Ducange, Innoc. III. P. P. lib. i. de Myster. : Missæ, cap. 10.)

” A fine piece of linen of an oblong-square form, which was formerly worn on the head until the priest arrived before the altar, and then thrown back upon the shoulders.” (Way, in Prompt. Parv. p. 11.) It was sometimes richly ornamented as well as the Albe, ” and in ancient representations appears,” says Mr. Way, ” like a standing collar round the neck of the priest.” ” Une aube et une amit parés de vi ymages en champagne d’or.” (Invent. MS. Reliquar. etc. Eccles. Camerac. sub anno 1371.)

” Upon his hede the amyte first he laieth.” Lydgate, MS. Lambeth Lib. Vide Halliwell in voce.

Embroidered or apparelled amices were generally used in the English Church previous to the reign of Edward VI. The apparels were sewed on to the amices, and, when there, were fastened round the neck; they formed the collar which is invariably represented on the effigies of ecclesiastics. When the amice was pulled up over the head, the apparel appeared like a phylactery. (Pugin’s ‘ Glossary of Ecclesastical Costume.’)

In the plate representing the Procession of Palms, in Picart’s ‘ Ceremonies Religieuses,’vol.ii., the officiating clergy are figured wearing apparelled amices on their heads.

ANADEME.

A diadem or fillet, wreath, chaplet, or garland. ” Upon his head, An anademe of laurel fronted well The sign Aquarius.” Ben Jonson`s Masque of Beauty.

“And for their nymphals, building amorous bowers, Oft dressed this tree with Anademes of flowers.” Drayton’s Owl.

“A band to tie up wounds” is called by Minshew an “anadesm.”

ANAPES, FUSTIAN ANAPES.

” Mock velvet, or fustian anapes.” (Cotgrave.) A species of fine fustian, probably made at Naples, à Naples, as we have now a silk called ” gros de Naples.” Fustian anapes is mentioned in ‘The strange Man telling Fortunes to Englishmen,’ 1662. “This,” remarks Mr. Halliwell, ” is, of course, the proper reading in Middleton’s Work, iv. 425: ‘Set a fire my fustian an ape`s breeches.’ “

ANELACE.

(Also in French, alenas, alinlas, analassc, anlace.)

A broad knife or dagger worn at the girdle. ” Genus cultelli quod vulgariter Anelacius dicitur.” (Matthew Paris, p. 274, and in many other passages.)

” An anelace and a gipeciere all of silke Hung at his girdle white as morwe milke.”

Chaucer, Canterbury Tales. ” Or alnilaz and god long knif.” Havelock the Dane, line 2554.

The termination laz is said to signify latus, a side, the waist. ” Germanis laz olim latus significabat; hinc Anelacius, Schiltero, est telum ad laterale: Seitengunches. Adel. (Ducange, ed. 1840.) Sir S.R. Meyrick says, ” An anelace or anelacio, probably so called from having originally been worn in a ring;” or rather, appended to one at the girdle, as the form of the blade would not admit its being worn in a ring.

In Skelton’s ‘ Engraved Specimens,’ Plate LXI I., are five anelaces, the earliest in point of date being of the time of Edward IV. Its mention by Matthew Paris, however, shows that it was a well-known weapon in the thirteenth century, and we have examples in monumental brasses and sculpture of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries of what are supposed to be anelaces, though differing in form from those of later date. Our examples are from a brass in Northleach Church, of the fourteenth century, and specimens from Demmin and Skelton, temp. Edward IV. and Henry VII.

ANLET.

“An annulet or small ring.” (Yorkshire: Halliwell, in voce.)

In ‘ The Device for the Coronation of Henry VII.,’ published by the Camden Society, in the volume of ‘ Rutland the Papers,’ the queen is directed to wear ” a kirtell of white damask daie (raie ?) cloth of gold, furred with mynever, pure, garnished with anletts of gold,” which the editor considers to mean agletts or tags. (See under AGLET.)

APPAREL.

This word is used not only for general dress, but to specify the embroidered borders of ecclesiastical vestments. (See under ALBE and AMICE.)

APRON, APORNE, NAPRON.

(From nappe, cloth, French ; or, according to some, from Saxon sepopaen.)

The barm-raegl or barm- cloth of the Anglo-Saxons, from barm, the lap or bosom.

The leathern apron worn by smiths, &c., is seen in an illumination of the time of Edward II., Sloane MS. 3983. It is called barm-skin in Northumberland, and in Lincolnshire they have a proverb, ” As dirty and greasy as a barm-skin.” The term barmfeleys for the same article occurs in a curious poem in ‘ Reliq. Antiq.’ i. 240; Halliwell. “A barm cloth as white as morrow milke, Upon her lendes, full of many a gore.” Chaucer, Canterbury Tales. Waiters, from wearing an apron, were called apron-men and aperners. ” It was our pleasure, as we answered the apron-man.” Rowley’s Search for Money, 1609. “Where’s this aperner?” Chapman’s May Day, 1611.

From the useful garment of the housewife, domestic, and artisan, the apron became, towards the end of the sixteenth century, a portion of the dress of a fashionable lady.

” These aprons white of finest thrid, So choicely tide, so dearly bought, So finely fringed, so nicely spred, So quaintlie cut, so richlie wrought ; Were they in worke to save their cotes, They need not cost so many grotes.” Stephen Gosson’s Pleasant Quippes for upstart new-fangled Gentlewomen, 1596.

In Massinger’s ‘City Madam,’ 1659, we hear of young ladies wearing “green aprons,” which they are ordered to ” tear off,” being no longer fashionable. In 1753 the lady is directed to “pull off” her ” lawn apron with flounces in rows.” (‘ Receipt for Modern Dress.’)

In 1744 aprons were worn so long that they almost touched the ground. They were next shortened, and lengthened again before 1752, as a lady is made to exclaim, in the ‘Gray’s Inn Journal’ of that date (No. 7), that “Short aprons are coming into fashion again.”

ARBALEST, ARBLAST, ALBLAST.

(Arcubalista, Latin; arbaleste, ballestre, French; Armbrust, Hebelarmbrust, German). A cross-bow.

“Shoot to them with arblast, The tailed dogs for to aghast.” Richard Coeur de Lion, 1. 1867. ” Both alblast and many a bow, War redy railed upon a row.” Minot’s Poems, p. 16.

” The cross-bow,” says Sir S. R. Meyrick, ” was an invention of the Roman Empire in the East, suggested by the more ancient military engines used in besieging fortresses: hence its name Arcubalist or Arbalist, compounded of Latin and Greek words. It was introduced into England at the Norman Conquest, but Richard Cœur de Lion is said first to have brought it into general fashion.” (Skelton’s Engraved Specimens,’ vol. ii.)

Guiart says the French received them from Richard I., about the year 1191, and remarks:

“Nul ne savoit riens d’arbalaste, Et temps dont je faiz remembrance, En tout le Royaume de France.” Branches des Royanx, Chron. Nat. vii. 49, 1. 616.

Guillaume le Breton supports this assertion by stating, that in the early part of the reign of Philip Augustus there was not a person in the French army who knew how to use an arblast :

” Francigenis nostris illis ignota diebus, Res erat omnino quid ballistarius arcus, Quid ballista foret, nee habebat in agmine toto Rex, quemquam sciret armis qui talibus uti.” Philip, 1. 2.

And, speaking of the death of Richard Coeur de Lion, who was mortally wounded by a shot from a cross-bow, he says: ” Hac volo non alia Richardum morte perire, Ut qui Francigenis ballistas primitus usum, Tradidit ipse sui rem primitus experiatur, Quamque alios docuit, in se visu sentiat artis.”

The Sieur de Caseneuve and Père Daniel have shown, however, that Richard and Philip Augustus only revived the use of the arblast, which had been prohibited by the Twenty-ninth Canon of the Second Council of Lateran, held in 1139, during the reign of Louis le Jeune in France and Stephen in England.

“Artem illam mortiferam et Deo odibilem Ballistariorum et Sagittariorum adversus Christianos et Catholicos exerceri de caetero sub anathemate prohibemus „ – a curious fact in the history of arms, and which caused the death of Richard by the weapon he had re-introduced in defiance of the injunction to be considered as an especial judgment of God. (Vide’ Histoirc de la Milice tome Françoise,’ i. liv. iv. p. 425.)

That the cross-bow was used for the chase in Normandy and England in the eleventh century has been stated on the authority of Wace, who tells us that William (the Conqueror) was in his park at Rouen when he received the news of the death of Edward the Confessor, and that he had just strung his bow and charged it, and given it to a varlet to hold for him. But Wace uses the word arc, and not arbalète or arblast :

” Entre ses mainz teneit un arc Encordé l’aveit é tendu Et entésé é desentu; ” and it is open to the doubt whether this was a long-bow. Certainly no cross-bow is seen in the Bayeux Tapestry. Also, on the day William Rufus was slain in the New Forest, his brother Henry, who was hunting in a different part of it, found the string of his bow broken, and, taking it to a ” vilain ” to be mended, met with an old woman there, who told him he would soon be king. Wace, who relates this anecdote, says : ” Mais de son arc quant fu tenduz Fu un cordon de l’arc rompu. ” ” But when his bow was bent, a string of it was broken,” which would imply that the bow had more than one string, and, therefore, prove it to be a cross-bow, of the kind used for hunting, and called prodd, which had two.

In Domesday Book mention is made of Odo the Arbalister, as a tenant in capite of the king of land in Yorkshire ; and the manor of Worstead, Norfolk, was, at the time of the Survey, held of the Abbot of St. Benet at Holme by Robert the Cross-bowman. The arblast had what is called a ” stirrup ” at the end of the stock, into which the foot was put in the act of stretching it. ” Balista duplici tensa pede missa sagitta.” – Guillaume le Breton. (Balista grossa ad Stephani Twini Balasterii or Arbalete a tour.) It was wound up by a portable apparatus called a moulinet, cranequin, or windlass (” balista grossa de molinelles “) carried at the girdle. This form of arblast was used in battle to the middle of the fifteenth century, by the Genoese especially.

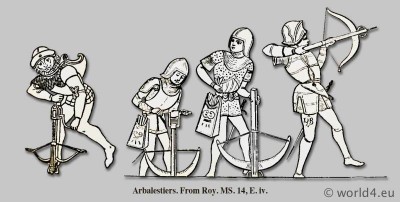

In our illustration from a MS. of the reign of Edward IV., the two first archers are represented winding the bow. The third is drawing an arrow from his quiver, his foot being still in the stirrup, and the fourth is shooting. The smaller cross-bow was bent by means of an instrument called a ” goat`s food ” lever (Geisfuss, German).

ARISAD, AIRISARD.

A long robe or tunic girdled round the waist, worn by females in Scotland as late as 1740. (‘ Poems,’ by Alexander McDonald.) Martin describes it as a white plaid, having a few small stripes of black, blue, and red, plaited all round, and fastened beneath the breast with a belt of leather and silver mixed like a chain.

ARMESIN TAFFETA.

“A kind of taffeta mentioned by Howel in his 25th section.” (Halliwell, in voce) “Armoisin ou armosin: sorte de taffetas faible et peu lustre.”

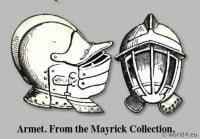

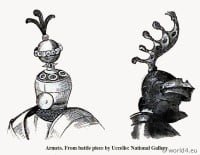

ARMET.

A form of helmet worn in the latter half of the fifteenth century. In the ‘Memoires de J. Duclercq,’ it is stated that, at the entry of Charles VII. of France into Rouen, the Count de St. Pol had a page, ” qui portoit un armet en sa teste de fin or richement ouvré.” (Tome i. p. 349 ; Bruxelles, 1823.)

Claude Fauchet and La Colombierre use the terms armet and salade indifferently ; but Guillaume de Bellay, or, at least, the author of the work attributed to him, makes a remarkable distinction between them in his description of the men-at-arms, who, according to the ‘ Ordonnances’ of Francis I., he says, should wear the “armet avec ses bavières,” whilst the chevaux legers should be armed “d’une salade forte et bien coupee a vue coupée.” (Discipl. Militaire, 1. i, fol. 29. Vide also Père Daniel, Hist, de la Milice Franc, vol. i. p. 397, edit. 1721 ; and Allou, ‘Etudes sur les Casques du Moyen Age,’ p. 48.)

Palsgrave has merely, “Armet, a head pese of harnesse,” (f. 18.) In Sir S. R. Meyrick’s Collection was a helmet, dated 1558, brought from the Château de Brie, which belonged to the Dukes of Longueville. It is thus described in Skelton’s ‘Engraved Specimens of Arms and Armour,’ Plate XXIX.: “Fig. 1. The armet grand et petit, so called from being

capable of assuming either character, seen in profile. The wire which appears above the umbril is to hold the triple-barred face guard.” ” Fig. 2. -The same viewed in front with the oreillettes closed ; but the beaver removed so as to render it an ‘armet petit.’

I give these figures here, as I am by no means prepared to deny that this helmet may be of the kind included in the word “armet,” though others are of opinion that the distinguishing feature of the armet was its opening at the back.

Demmin calls it the most complete form of helmet, and classes it with the casque. It is almost impossible to decide from mere description, but I believe the term ” armet ” to have been given to the earliest kind of close helmet which began to be adopted towards the end of the fifteenth century; indeed, to be the French and Italian word for helmet itself, which is but the diminutive of helm, and is not met with before that period.

The ponderous helm (heaume) had been for some time past only used for the tournament, and the visored bascinet, only worn in battle. The next improvement was a combina- tion of these, and the production of a complete head-piece, which received from the Italians the name of elmetto or armetto, the little helm; Anglicè, helmet, or armet; “Armet, petit heaume,” French. The word eventually was applied generally to ‘any head-piece. One armet in the Meyrick Collection had a round plate at the back ; and in the curious painting by Uccello in the National Gallery, said (but incorrectly, as I believe,) to represent the battle of St. Egidio, in 1417, several of the knights are depicted with head-pieces exhibiting this peculiarity. Another painting, at Hampton Court, ‘ The meeting of Francis I. and Henry VIII. of England in the Vale of Ardres,’ presents us with several instances, but none that illustrates its use. It is presumed, however, its object was to prevent the point of a lance entering where the helmet opened behind.

ARMILAUSA, ARMIL, ARMYLL.

“A body garment, the prototype of the surcoat.” (Meyrick.) The Emperor Maurice in his ‘‚Strategies ‘‚ tells us the short tunics which reached military only to the Knees, they were put on over the armour. Isidorus derives the word from armiclausa : ” Armelausa vulgo vocata quod ante et retro divisa, atque aperta est ; in armos tantum clausa quasi armiclausa.” (Origin, liber xix. cap. 22.) Wachter and other German authorities derive it from words expressive of a tunic without sleeves ” Non manicata, absque manicis, a los, destitutus “Tunica serica sine manicis;” “Armel-laus significare potuit sine brachiis;” while, the other hand, Schiller suggests, “Aermellatz: ein latz mit aermeln,” a waist coat with sleeves!

In ‘The Device of the Coronacion of King Henry VII.,’ we read: “The King then, gird with his sword and standing, shall take the armyll of the Cardinall, saying these words: ‘Accipe armillam’ ( ‘Accipite armulam’ in the MS.); and it is to wete that armyll is made in maner of a stole, wovyn with gold and set with stones, to be putt by the Cardinall aboute the Kinges necke, and commyng from both shudres to the Kinges both elbowes, wher it shall be fastened by the said Abbot with laces of silke on evry elbowe, in twoo places, that is to saye, above the elbowes and bynath.” (‘ Rutland Papers,’Camden Society, page 18.) Camden says,quoting the ‘ Book of Worcester,’ that in 1372 they first began “ to wanton it in a new round curtail weed, which they called a cloak, and in Latin, armilausa, as only covering the shoulders.” (Remaines, p. 195.) This description corresponds with that of the armyll which came ” from both shoulders to the king’s both elbows,” and a cloak so formed may be seen in illuminations about that date ; but it certainly cannot be

said to be made ” in manner of a stole.” Nor could it be conveniently fastened with laces of silk both above and beneath the elbows. It is very probable that in this, as in many other instances, the same name has been at various periods bestowed on widely differing garments. Mr. Taylor, in his ‘Glory of Regality,’ p. 81, uses some very ingenious arguments to prove that the armyll in our coronation ceremony is an error arising from a confusion of the stole with the bracelets armilla. The word, at all events, occurs in English costume as early as the time of the Anglo-Saxons. In a deed of Ethelbert we find, ” Armilasia oloserica camisiames ornatam prædicto Monasterio garanter obtuli.” (Dugdale, ‘Monasticon.’) And as it is expressly said to have been put on after the king has been girt with the sword, it must have been open at each side, and resembled not the stole but the dalmatic or the tabard, the latter of which, particularly, might be described as having and not having sleeves in the usual acceptation of the word. The accompanying figure, from an illumination in a MS. in the Royal Collection, is supposed to represent one form of the armilausa as described by Camden, but not “ante et retro divisa,” according to Isidorus.

ARMING DOUBLET.

A loose doublet with sleeves, worn over the armour in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Sir John Paston, 3rd June, 1473, I3th of Edward IV., writes: “Item, I pray you to sende me a new vestment off wyght damaske for a dekyn (deacon), which is among myn other geer at Norwich. I will make an armyng doublet of it.” (Paston Letters.) In explanation of this curious message, it is to be observed, that white was the field of the Paston arms, and that the word “arming” was used in the sense of coat armour is apparent from the lines of Drayton : “When the Lord Beaumont, who their armings knew, Their present peril to brave Suffolk shewe.” Poems, p. 63. “First. 2 Armynge Doublets.” (Th’ Apparell for the Feld, &c., MS. L. 8, Coll. of Arms, fol. 85.) ” An Armyng Doublet of crimson and yellow satin, embroidered with scallop shells, and formed down with threads of Venice gold.” (Inventory, 33rd of Henry VIII. 1542; Harleian MS. No. 1419.) “Item, That every man have an Arming Doublette of fustian or chanvas.” (Order of the Duke of Norfolk, 36th Henry VIII. ; MS. Coll. Arms, W. S.)

ARMING GIRDLE.

The belt which carried the arming sword or estoc. (Vide ARMING SWORD.) Cotgrave renders ” Ceinture à crouppière : a belt, arming girdle, or sword girdle of the old fashion.” ( Vide also Florio in Balteo.)

ARMING HOSE.

In the Inventory of Henry VIII.’s Wardrobe, taken in 1542, before quoted, we find, ” a paire of arming hoze of purple and white satten, formed down with threads of Venice silver.” (Harleian MS. No. 1419.) I presume these to have been trunk hose, worn only under tassets which would not entirely conceal them. (See ARMOUR.)

ARMlNG SPURS.

“Item, 2 peer of Armyng Spores.” (‘ Th’ Apparell for the Feld.’)

ARMING SWORD.

A small sword, called in French estoc, It was worn naked, passed through a ring suspended from the belt on the left side, when a man was armed to fight on foot; but when on horseback the weapon hung on the left side of the saddle-bow. (S. R. Meyrick, ‘ Archæologia,’ vol. xx.) “Item, an arming sword.” (Th’ Apparell for the Feld, ut supra.) ” Some had their armynge swordes freshly burnished.” (Hall’s’ Chronicles,’ Henry IV. f. I I.) Sir John Paston, under date, 30th April, 1466, writes to his brother: “Sir John of Parr is your friend and mine, and I gave him a fine arming sword within this three days.” “Armynge swordes with vellet (velvet) skaberdes, xi.” (Brander’s MS. ‘ Inventory of Royal Stores,’ 1st Edward VI., 1546.)

ARlMINS.

Cloth or velvet coverings of the staves of halberds, pikes, &c., sometimes ornamented with fringes and gilt-headed nails. “You had then armins for your pikes, which have a graceful shew, for many of them were of velvet embroidered with gold, and served for fastness when the hand sweat: now I see none, and some inconveniences are found by them.” (Art of Training, 12mo. 1622.)

ARMOUR.

ARROW.

The arrows used by the early inhabitants of the British Islands were formed of reeds headed with flint or bone. The Welsh Triads celebrate Gurneth the Sharp-shooter as shooting with reed arrows; and Abaris, the Hyperborean priest, is said by Herodotus to have carried a reed arrow with him: and though the Triads are not of the age to which they have been attributed, and the story of Abaris is apocryphal, these allusions show that reed arrows had been used in very ancient times by the Britons. The arrows of the Saxons and the Danes were headed with iron; but both these nations appear to have used the bow for hunting or for pastime, more than for battle. Henry of Huntingdon reports William, Duke of Normandy, to have spoken of the Anglo Saxons as a nation not having even arrows. With the Northmen archery was considered “an essential part of the education of a young man who wished to make a figure in life” (Strutt), and the shafts used by them are distinguished by the various names of arrows, bolts, bosons, piles, quarrels, standards, and vires. The arrow was the shaft of the long-bow, although occasionally shot from the arblast, or or cross-bow; but the other descriptions were appropriated to the latter alone.

The old English arrow, “the cloth-yard shaft,” or standard arrow, made famous by our gallant yeomanry of the Middle Ages, was formed of ash, asp, oak, hardbeam, or birch, headed with burnished steel, and winged with the feathers of the grey goose or the peacock, and sometimes of the swan, as well as other birds.

Roger Ascham tells us there are three essential points in the composition of an arrow: “A shaft hath three principal parts – the stell (or wand), the fethers, and the head. Stells be made of divers woodes, as brasell, Turkie woode, fustiche, sugarcheste, hardbeame, byrche, asshe, dake, servis tree, h ulder, blackthorne, beeche, elder, aspe, salowe. Birche, hardbeame, dake, and ash are best, though this depends on the shooter. Sheaffe arrowes should be of ashe, and not of aspe, as they be now adayes.”

The length of the arrow depended on the height of the archer. “In the true proportion of the human figure,” remarks Sir S. R. Meyrick, “it is found that the distance from the tip of the middle finger of one hand to that of the other, when at the utmost extension, equals that from the crown of the head to the soles of the feet. Now, if such be the length of the bow-string, and the shaft half that size, a man of six feet high would use a cloth-yard arrow. Probably this rule was seldom, if ever, attended to; yet, as the arrow was drawn to the ear, leaving as much beyond the bow as would reach the middle finger end, if not clasped, and the ear was brought over the centre of the chest, the result was precisely the same.”

Ascham says it is better to have them “a little too short than over long; no one fashion of steele can be fit for every shooter.” English arrows had forked heads and broad heads; but Ascham accounted those with round pointed heads resembling a bodkin as the best. Sheaf arrows had flat heads for short lengths, and he recommends they should have a shoulder to warn the archer when he has drawn them far enough. “The nocke of the shaft is diversely made, for some be great and full, some hansome and litle, some wyde, some rounde, some longe, some with double nocke, whereof every one hath his propertye.”

In the old ballad of’ Robin Hood’ the nockes of the arrows are said to have been bound with white silk:

“An hundred shefe of arrowes good, With hedes burnished full bryght, And every arrowe an ell longe, With peacocke well ydight; And nocked they were with white silk. It was a semely sight.” Geste of Robyn Hode.

Chaucer’s Squire’s yeoman bore ” A shefe of peacocke arwes bryght and kene.”

Prologue to Canterbury Tales.

In the ancient ballad of ‘Chevy Chase,’ we read: “The swan’s feathers that were thereon ;” which in the more modern version is altered to “The grey-goose winge that was thereon.”

There appears to have been some difference between ” the flight ” or ” roving arrow, ” and” the sheaf arrow;“ but in what particular is not quite clear. “A sheaf” consisted of twenty-four arrows. “Pro duodecim flecchis cum pennis de pavonæ emptis pro rege, de 12 den.” (Lib. Comput. Garderobæ, sub an. 4 Ed. II. A.D. 1311. MS. Cotto Nero, G. viii.) An English bowman was, therefore, vauntingly said to bear four-and-twenty Scots in his girdle.

Matthew Paris mentions arrows headed with combustible matter, which were shot from bows into towns and castles, and also arrows headed with phials full of quicklime: “Missimus igitur cum spicula ignita” (p. 1090). “Et phialas plenas calce, arcubus per parva hostilia sagittarum super hostes jaculandas” (p. 1091). Mr. Demmin has given us a specimen of these, at a later period, from a drawing in the Hauslaub Library, Vienna. Arrows with wild fire and arrows for fireworks are mentioned amongst the stores at Newhaven and Berwick in the 1st of Edward VI. (Grose, Mil. Antiq. vol. ii. p. 270.) A curious particular respecting arrow-heads occurs in Swinden’s ‘History of Great Yarmouth: where the sheriff of Edward III, being ordered to provide a certain number of garbs (sheaves) of arrows headed with steel for the king’s use, is directed to seize, for the heading of them, all the flukes of anchors (” omnes alas ancarum “) necessary for that purpose, (Ibid. vol. ii. p. 269, note i.). In the 7th of Henry IV. (A.D. 1406) it was enacted that every arrow-head, or quarrel, should have the mark of the maker, under penalty of fine and imprisonment of the offending workman (ibid.), the making of arrow-heads constituting formerly a separate trade: ” Lanterners, stryngers, grynders, Arow-heders, maltemen, and corne-mongers.“ Cocke Lorell’s Boat, p. ro.

Throughout the fifteenth century the orders for making and providing arrows are numerous, the sheaf still consisting of twenty-four. In 1543 the King’s letter to the mayor and sheriffs of Norwich orders them to provide forty able footmen, “whereoff viii to be archers, evry oon to be furnyshed with a gode bowe and a case to carye it inne, Wt xxiiii. goode arrowes “ In 1559 the price of a sheaf of arrows was twenty-two pence.

In the reign of Elizabeth, when fire-arms were beginning to supersede the bow, arrows were made for shooting out of cannon and muskets. “Item, for a dozen arowheds for musketts.” “To William Fforde, ffletcher, for a dozen arrowes feathered, and heds for musketts, and a case for them, xxd“ (‘ Accounts of Robert Goldman, Chamberlayne of the Citie of Norwich,’ 1587.)

In 1595 there were in the Tower of London “Musket arrowes, 892 shefe,” and “one case full for a demi-culvering”; and at Rochester, “Musket arrowes with fier works, 109 shefe.” These were for use at sea, and are called by Lord Verulam “sprights.”

ASSASSIN, or VENGEMOY

“Signifies a breast-knot, or may serve for the two leading strings that hang down before, to pull a lady to her sweet-heart.” (Ladies’ Dictionary. London, 1694·)

ATLAS.

A name given to gowns and petticoats in the reign of Queen Anne – derivation uncertain. In 1712 was advertised for sale- “a purple and gold atlas gown,” “a scarlet and gold atlas petticoat edged with silver,” and “a blue and gold atlas gown and petticoat.” (Malcolm’s’ Anecdotes,’ vol. ii. p. 319.)

AVENTAILE.

(Aventaille, French.) The movable front to a helmet, or to the hood of the hauberk, through which the wearer breathed, and which, succeeding the nasal of the eleventh, preceded the visor of the fourteenth century. It was applied to all defences of the face, whether a continuation of the mail-hood, or a plate attached to the front of the helmet. One sort of aventaile may be seen in an illumination of a Latin Psalter of the thirteenth century, marked A. xxii. Royal MS., British Museum.

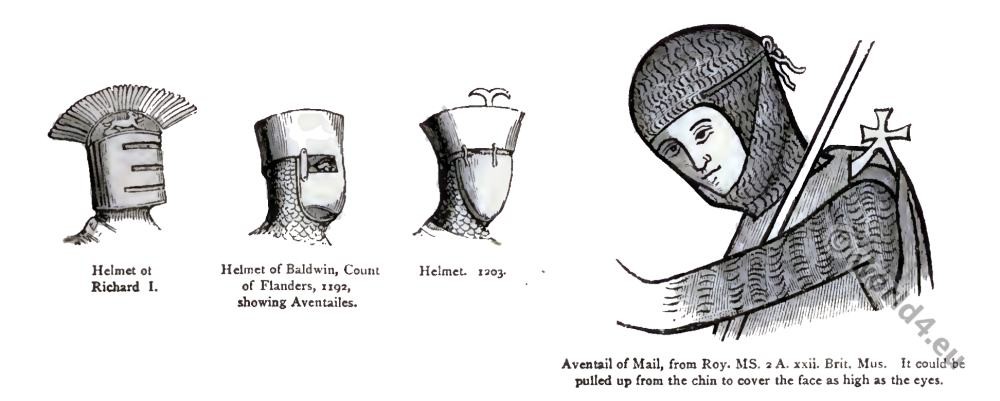

Helmet of Richard I. Helmet of Baldwin, Count of Flanders, 1192, showing Aventailes. Aventail of Mail, from Roy. MS. 2 A. xxii. Brit. Mus. It could be pulled up from the chin to cover the face as high as the eyes.

It is tied to the mail-hood, and forms a kind of chin-piece, thereby illustrating the following passages in the ‘Romance of Lancelot de Lac,’ quoted by Strutt, ‘Dress and Habits,’ vol. ii. p. 64, edit. 1842: “Le abat l’avantaille sur les espaules.” “Ote son escu et son hiaume, et si li abat l’aventaille tant ke la tieste remest toute nue.” “Ostes nos hiaumes et nos ventailles abatues.”

AULMONIÈRE.

The Norman name for the bag, pouch, or purse appended to the girdle of noble persons, and derived from the same root as “alms” and” almoner.” It was more or less ornamented, and hung from long laces of silk or gold. It was sometimes call cd alner:

“I will give thee an alner, Made of silk and gold clear.” Lay of Sir Launfal.

AUREATE SATIN.

A rich stuff thus mentioned by Hall, ‘Union of Honour,’ fol. 83, temp. Henry VIII.: “Their hosen being of riche gold satten called aureate satten, overauled to the knees with scarlet”

AVOWYRE.

Cognizance, badge, or. distinction. “Also a pensel to bere in his hand of his avowyre.” (Lansdowne MS .• British Museum, printed in ‘Archæologia,’ vol. xvii. p. 295.)

A General Chronological History of the Costumes of the principal Countries of Europe, from the Commencement of the Christian Era to the Accession of George the Third. BY JAMES ROBINSON PLANCHÉ, ESQ., SOMERSET HERALD. London: CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY. 1876.

Pingback: URL