Content:

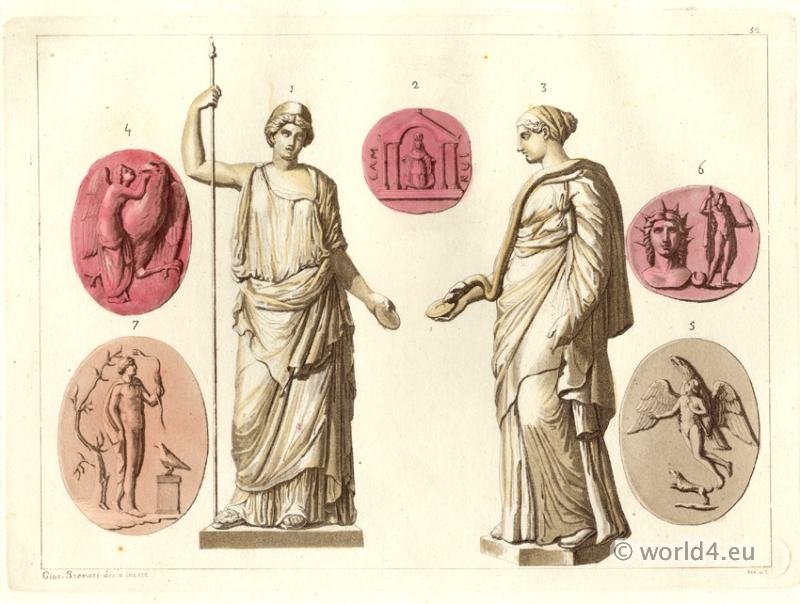

- The Toga and the Tunic of the Romans.

- The Roman head-dress.

- Materials used by the Romans for their ordinary clothing.

- Roman Head coverings. The petasus. The pileus. The infula, or mitre.

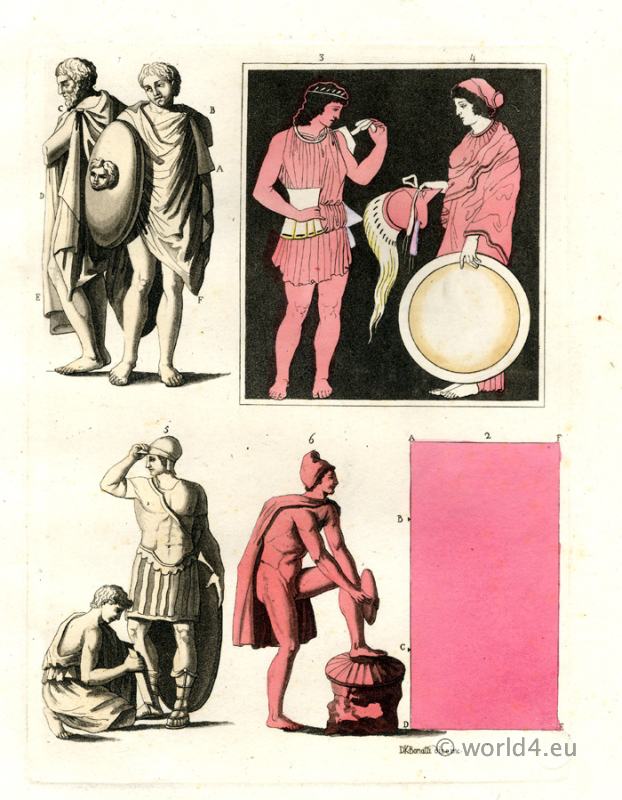

- The armor of the Romans.

- Dress of the Roman priests.

The necessary garments of mankind were never many: one adjusted to the body, reaching to the knee or mid-leg, for the men, and to the ankle for the women; another, ample enough to cover the whole person in inclement weather. These two, with or without some protection for the feet, comprised the whole of the clothing of many millions of human beings in pre-historic times, and under innumerable names have, with very few additions, descended, however altered in form or material, to the present day.

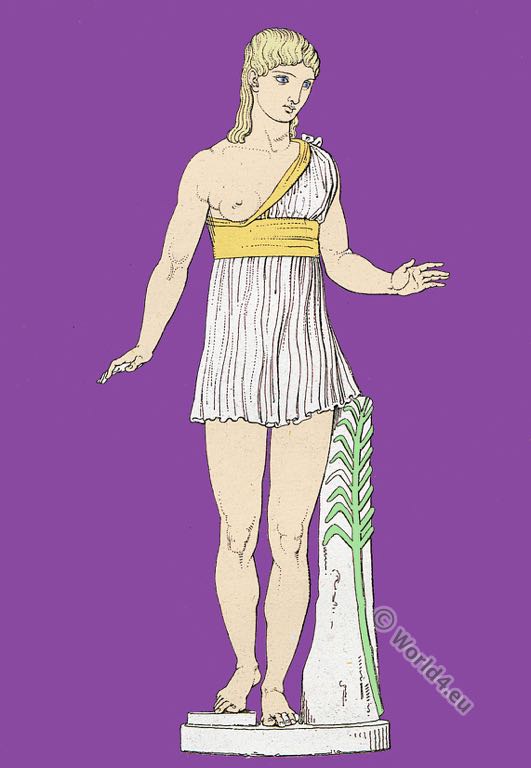

The first of these two garments was adopted by the Romans from the Greeks, who called it kitten*. The Latin name for it was tunica (a tuendo corpore), familiarized to us as tunic, which has within some few past years reappeared in the nomenclature of English costume, both civil and military. It was woollen or linen, according to the season, and originally had sleeves reaching scarcely to the elbow; but, in the time of the Emperors, to the wrist.

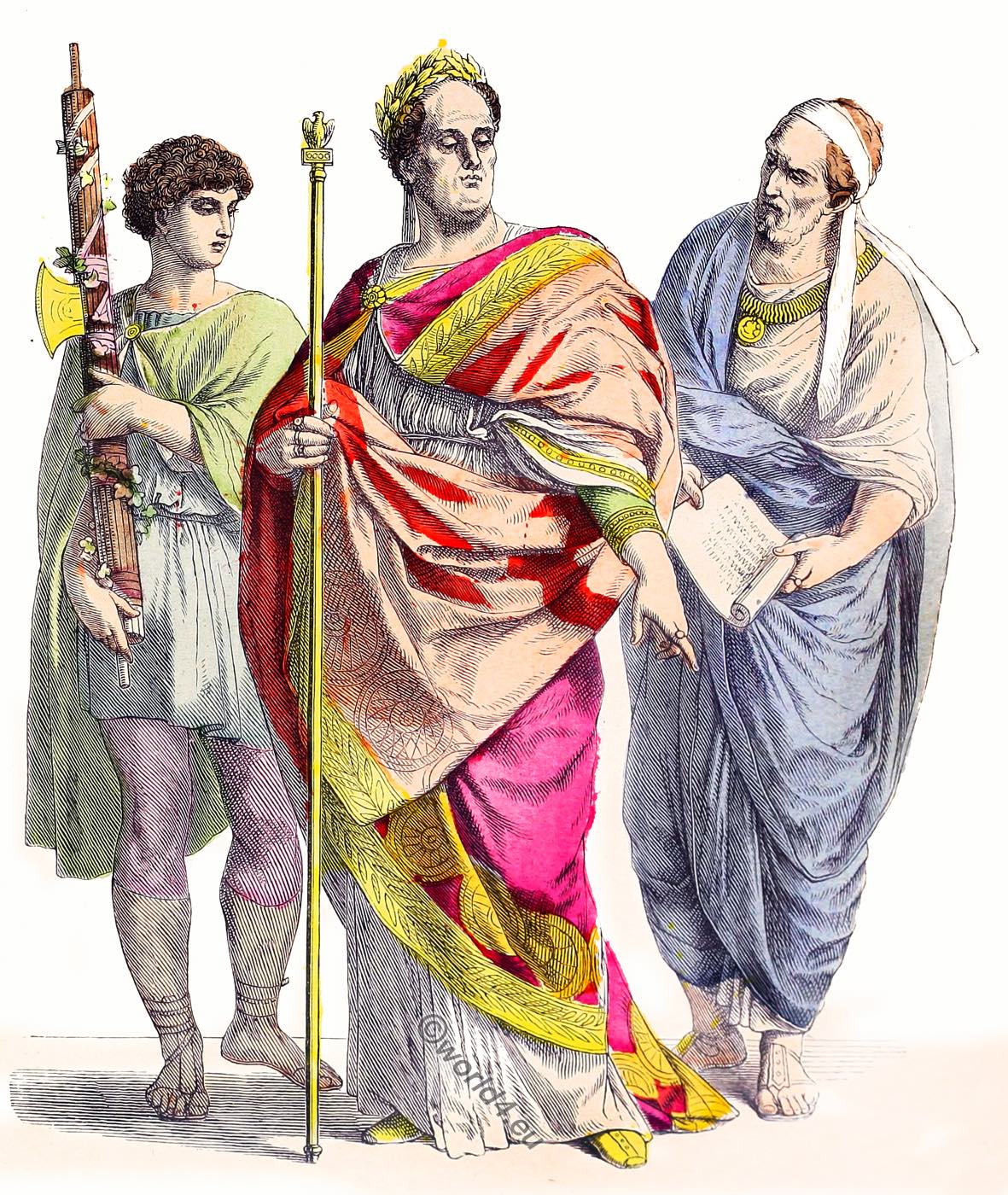

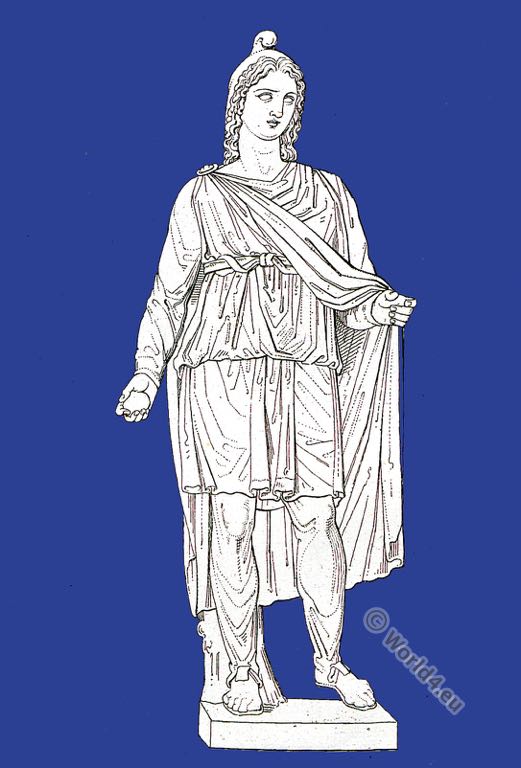

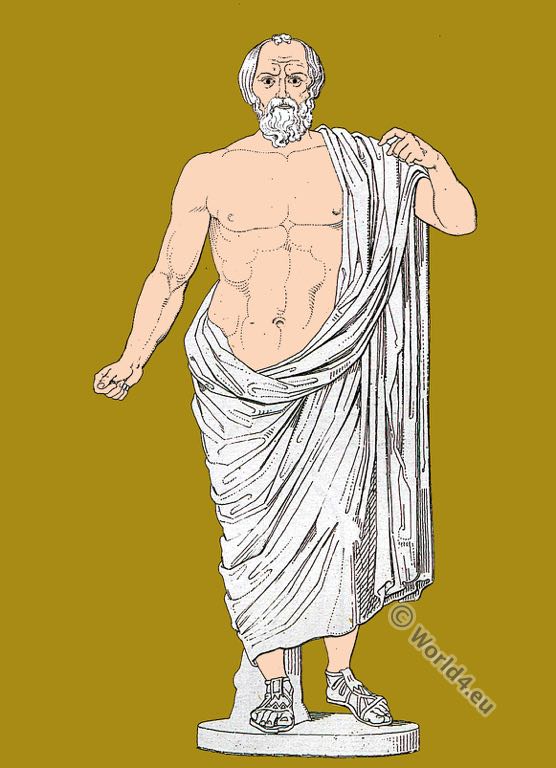

Over the tunic patricians wore that specially Roman garment, the toga (from togo, to cover), the exact form of which has been an endless subject of controversy. It was sufficiently ample to envelope the whole person when necessary, and to allow a portion to be pulled over the head for protection from the weather.

In fact, during the Republic it was the only garment, and may be likened in that particular to the plaid of the Scotch Highlanders, which was wrapped round the body much after a similar fashion.

The plebeians, wore as their outer garment a cloak of rough or coarse material, and of which there were three kinds viz., the lacerna, the byrrhus, and the penula each of which had a cowl attached to it to cover the head when required, and nearly resembled each other.

Montfaucon, speaking of the byrrhus, describes it as nearly the same thing as the lacerna, and adds, “It is also thought that the lacerna took the name of byrrhus from a Greek word signifying something reddish (Trvppos), it being usually of a red colour.” The name of byrrhus was subsequently given to a cowl, or other head-covering, whence the Italian term for a cap, berretta, French birette.

To these must be added a military mantle, the sagum or paludamentum, which the Romans had borrowed from the Gauls. It was a large open woollen cloak, and originally had sleeves, which were taken from it when it was brought into Italy. In dangerous times it was worn in the city of Rome by all ranks of persons except those of consular dignity. When worn by the general or the chief officers of an army, it was of a scarlet colour with a purple border. It has been sometimes confounded with the chlamys, which was principally worn by travelers.

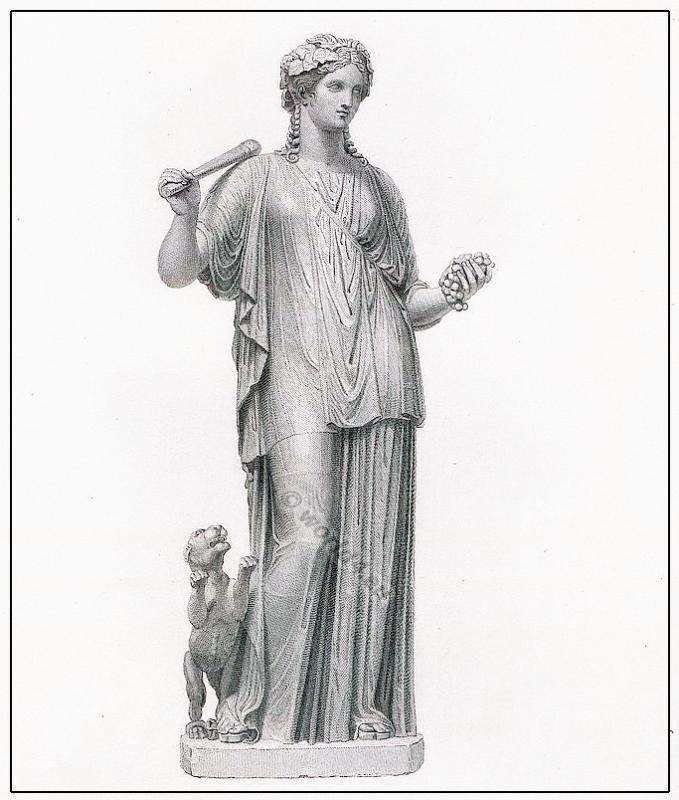

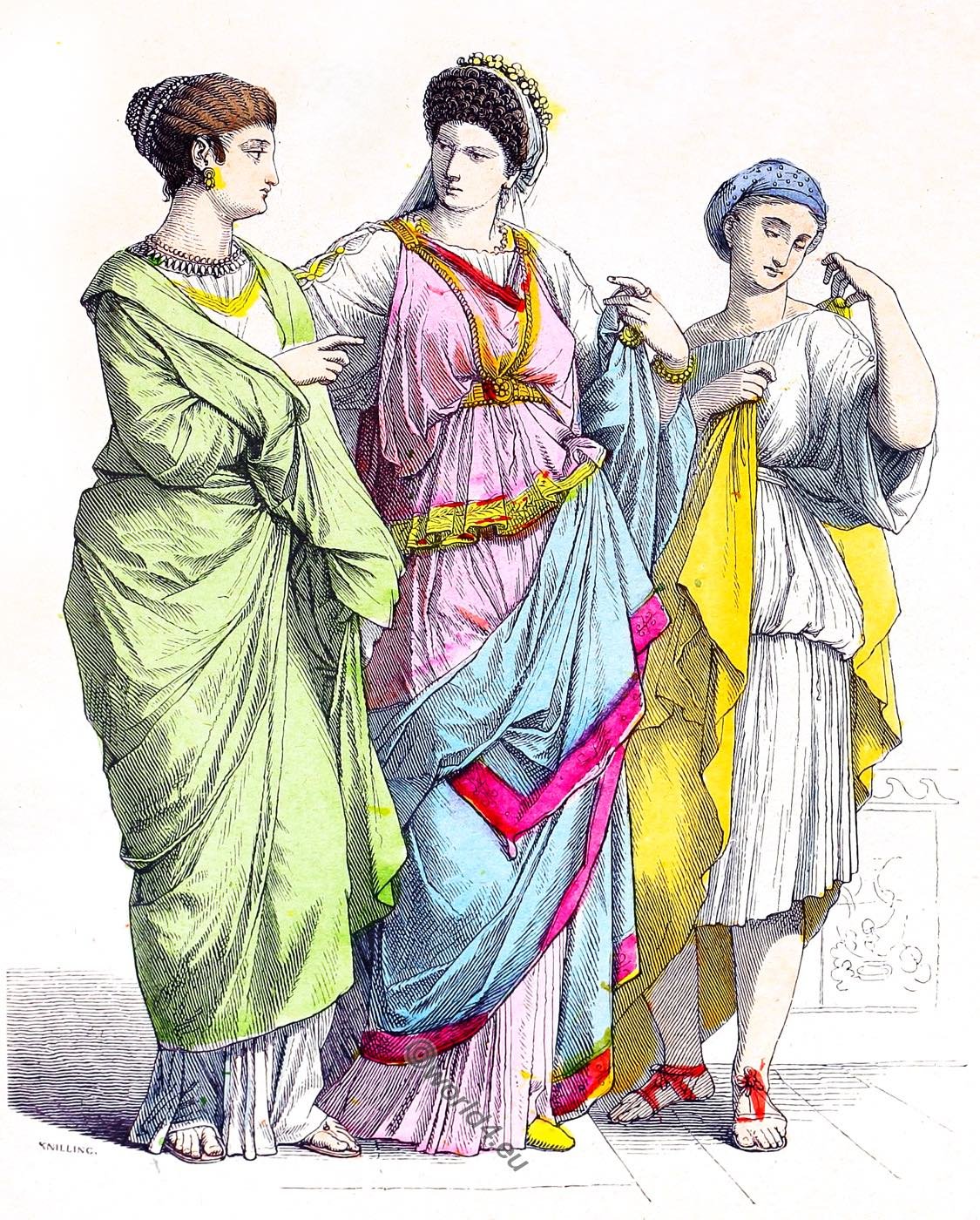

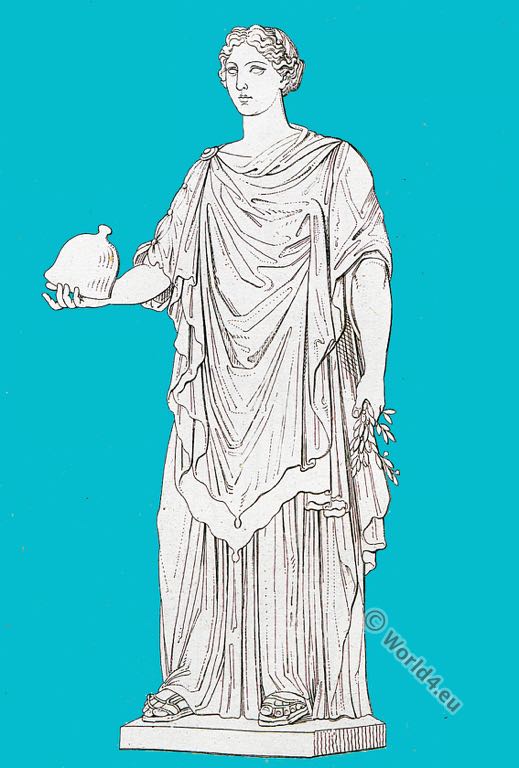

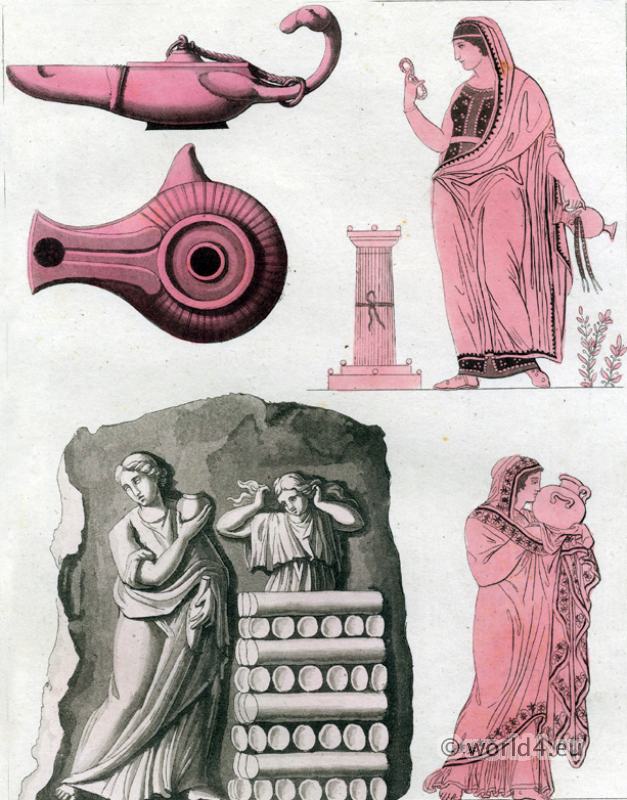

The women were clad in the long tunic, or the stola, a similar vestment, reaching to the feet, having a broad fringe or border at the bottom. Of outer garments they had a variety, all borrowed from the Greeks, the peplus or eanos (called by them also the palla or amiculum); the palliolum, a small cloak or veil; the theristrion, an exceedingly thin summer mantle; the chlamys and the penula, which they wore in common with the men; and several others of which we have the names but no definite description: and still be it remembered, whichsoever was worn, according to season, fashion, or convenience, it formed only one additional article of attire to the tunic or to the stola.

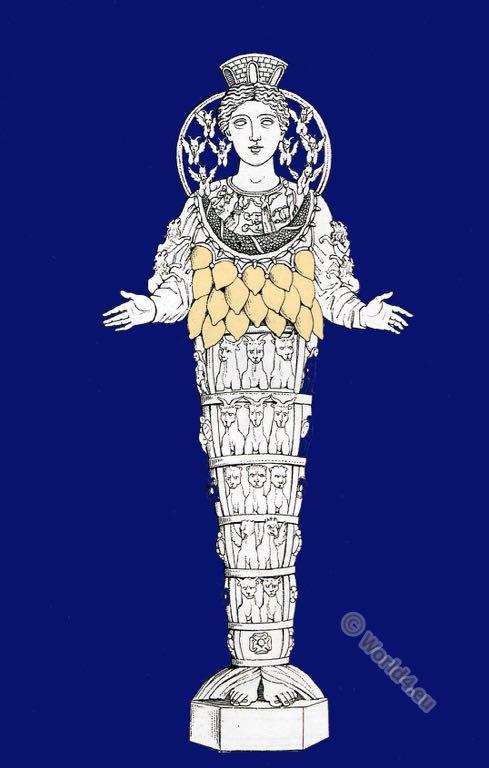

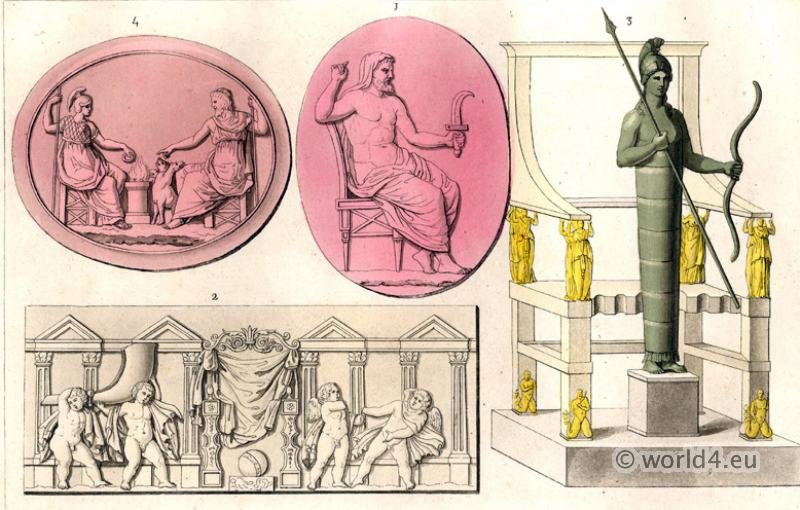

Dress of the Roman priests; of the vestals

The Romans, like all other nations, had peculiar dresses appropriated to peculiar offices and dignities. The Flamens or priests of Jupiter wore a cap or helmet, from its conical form called apex, with a ball of cotton wound round the spike. The Salii or priests of Mars, on solemn occasions, danced through the city of Rome clothed in an embroidered tunic, girt with a brazen belt, and over it they wore the toga pretexta, or the trabea, having on their heads a very high cap, a sword by their side, in their right hand a spear or a rod, and in their left, or depending from the neck, the ancilia, one of the shields of Mars.

The Luperci, or priests of Pan at the Lupercal, wore only a girdle of goat-skin about their waist. The vestal virgins wore a long white robe, bordered with purple; their heads were bound with fillets (the infulæ and vittæ). At their initiation their hair was cut off and buried, but it was permitted to grow again and be worn afterwards. Wreaths or crowns were given as rewards of military achievements or other noble deeds.

The corona castrensis, wrought in imitation of a palisade, was presented to whoever had been the first to penetrate into an enemy’s camp; the corona murialis, shaped in the semblance of battlements, to whoever had been the first to scale the walls of a besieged city; the civic crown, formed of oak leaves, to whoever had saved the life of a citizen; and the naval crown, composed of the rostra or beaks of galleys, to whoever had been the first to board an enemy’s vessel.

The Roman head-dress.

The Romans, like the Greeks, commonly wore their hair short, but combed it with great care, and perfumed it. The professors of philosophy let their hair and beards grow, to give themselves an air of gravity. The head-dress of the women in the days of the Republic was exceedingly simple; but as riches and luxury increased, the ladies’ toilet was proportionately extended, and obtained the name of “the woman’s world,” mundus muliebris; a title adopted by John Evelyn in the reign of Charles II. for a satirical poem on the female fashions of that period.

Above: Ancient Roman crowns and wreaths. Corona triumphalis, obsidimalis, civica, muralis, castrensis, navalis.

Julius Caesar is said to have worn a wreath of laurel to conceal his lack of hair, baldness being accounted a deformity amongst the Romans. In the time of his successors, such as were bald used a kind of peruke, made with false hair upon a skin, and called capillamentum or galericulum “crines ficte vel supposite.”

The ladies of the Roman Empire frizzled and curled their hair in the most elaborate manner, adorning it with ornaments of gold, pearls, and precious stones, garlands of flowers, fillets, and ribbons of various colours.

The back-hair was enclosed in a net or caul after the Grecian fashion, enriched sometimes with embroidery, and made so thin that Martial sarcastically called them bladders.

Slaves, for distinction sake, wore long hair and beards, but when anyone was manumitted he shaved both head and chin, and assumed the woolen cap called the pileus.

The ancient Romans permitted their beards to grow, until Publius Ticinius Maenas, about 450 years after the building of Rome, brought barbers from Sicily, and first introduced the custom of shaving which prevailed till the time of Hadrian, who, to conceal certain excrescences on his chin, revived the fashion of wearing beards; but after his decease it was neglected, and shaving was resumed.

Habits of Roman slaves. Origin of the bulla.

The slaves in Rome wore habits nearly resembling the poor people. Their dress, which was always of a darkish colour, consisted of the exomis or sleeveless tunic, or the lacerna, with a hood of coarse cloth, and the shoes called crepidæ.

The Roman boys who were sons of noblemen wore a hollow ball of gold, called bulla, which hung from the neck upon the breast. The origin of this practice amongst the Romans was, according to Macrobius, the gift of a bulla by Tarquinius Priscus, the conqueror of the Sabines, to his son, who, at fourteen years of age, had killed an enemy with his own hand. The bulla was made hollow for the reception of amulets against envy. A beautiful one was in the exquisite collection of the late Mr. Samuel Rogers. Our engraving is from one in the British Museum. Sons of freedmen or of poor citizens wore the bulla made of leather.

Materials used by the Romans for their ordinary clothing

Respecting the materials known to the Romans for their ordinary clothing, they appear to have been limited to woollen, linen, and silk. Linen, we learn from Herodotus, was imported to Greece from Colchis and Egypt.

The women used it earlier than the men, and at all times in much greater quantities. Pliny, citing a passage from Varro, says it had long been a custom in the family of the Serrani for the women not to wear robes of linen, “which being mentioned as a thing extraordinary,” observes Mr. Strutt, “proves that linen garments were used by the Roman ladies in times remote.” A vestment of this kind, called supparum, was worn by the unmarried Roman females as early as the time of Plautus.

Silk unknown to them during the Roman Republic

Silk appears to have been unknown to the Romans during the Republic. It is mentioned shortly afterwards, but the use of it was forbidden to the men. Vespasian and his son Titus are said to have worn robes of silk at the time of their triumph, but it is thought that the garments were only embroidered with silk, or that they were made of some stuff with which silk was interwoven; for Heliogabalus, A.D. 218-222, is described as being the first Emperor who wore a robe of pure silk; and we learn from Pliny that the silk manufactured in India was esteemed at Rome too thick and close for use. It was therefore unravelled and wrought over again, in the island of Cos, with linen or wool, and made so thin as to be transparent.

In the time of the Emperor Aurelian, A.D. 161-180, a vestment of pure silk was estimated at so high a price that he refused to allow his Empress one on that account.8 The Emperor Justinian, by the agency of two Persian monks, introduced silkworms at Constantinople in the sixth century, and in the following reign the Sogdoite ambassadors acknowledged that the Romans were not inferior to the natives of China in the education of the insects and the manufacture of silk.

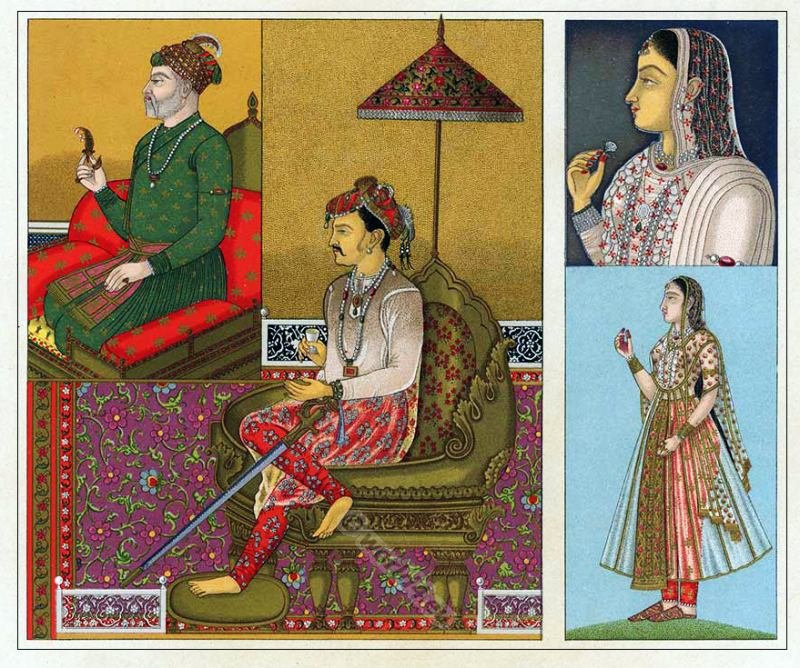

When the arts fell into a total decline, glitter of materials became the sole substitute for beauty of form, and Oriental splendour characteristically denoted the gradual extinction of the Roman Empire in the West.

Corybantian Dance.

Korybantes (Corybants). The warriors depicted on the neoattic relief perform a weapon dance. This dance consisted of rhythmically striking the shield of the next warrior with the sword. The work dates from the first half of the 1st century BC and is a copy of an older Athenian relief. Exhibited in the Vatican Museums.

Korybantes (Greek Κορύβαντες) are vegetation demons and orgiastic ritual dancers accompanying the goddess Cybele (in the Roman Empire and Magna Mater). They come from Greek mythology and are on the Anatolian kingdom of Indo-European Phrygians (there Berekyndai) be attributed. Korybantian dances were danced among others in the Gymnopaedien.

The Gymnopaidia was “the festival of the unarmed boys”. The Gymnopaidien were the so-called “naked games”, it consisted mainly of choral competitions of three age groups of men (boys, youth, adult men to 30 years). It was held at the Agora in Sparta, the line was probably in the hands of the ephors, the entire male population of Sparta took part. The Gymnopaedie was one of the three most important festivals of Sparta in honor of Apollo beside the Hyacinthia and Karneen.

Roman Head coverings. The petasus. The pileus. The infula, or mitre.

Both Greeks and Romans generally went bare-headed, but they had several sorts of head-coverings for special circumstances, the two best known being the petasus and the pileus.

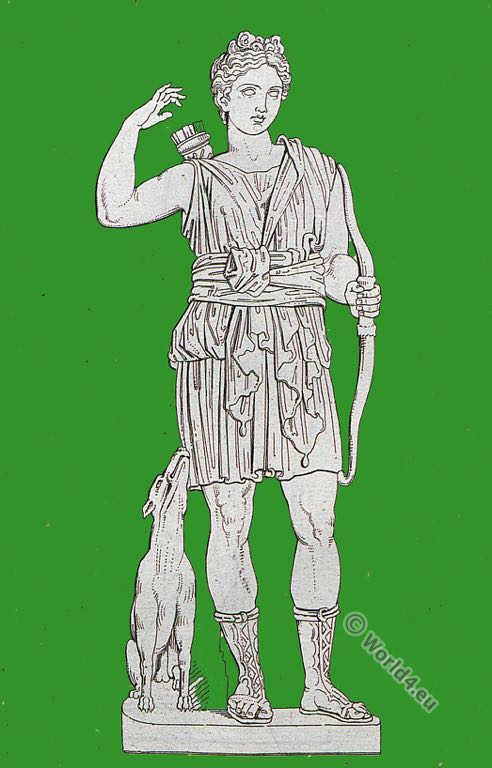

The petasus was a low-crowned hat with a broad brim, which might be profanely likened to the celebrated mambrino of Don Quixote, originally a barber’s basin. It was worn chiefly by travellers, and for that reason it is usually accorded to the figure of Mercury, with the addition of wings. Caligula permitted the people of Rome to wear the petasus at the theatre, to shade their faces from the sun.

The pileus was a woollen cap, worn by the Romans at the public games and at festivals, and by such as had been slaves, after they had obtained their freedom. It was also generally worn by sailors.

There was a head-dress called infula, or mitre, which was a white woollen fascia or riband, or, as some say, white and yellow which was tied round the head from one temple to the other, and fastened with a knot behind, so that the two ends of the bandage might hang down, one on each side. It appears to have been a ceremonial ornament, and worn only by those persons who sacrificed. The girdle was called mitra by the Greeks.

Amongst the most favourite ornaments of the Roman ladies we find ear-rings, necklaces, and bracelets. Their extravagance in the purchase of these articles is commented upon by contemporary writers with a severity not exceeded in after-ages by the censors of the fashions of their time.

Pliny says, “They seek for pearls at the bottom of the Red Sea, and search the bowels of the earth for emeralds to decorate their ears.” And Seneca tells us that “a single pair was worth the revenue of a large estate,” and that some women would wear at their ears “the price of two or three patrimonies,” almost the very words of Taylor the Water-poet, in his condemnation of the fashions of the reign of James I. Ear-rings and bracelets were also worn by some effeminate young men, and finger-rings by both sexes.

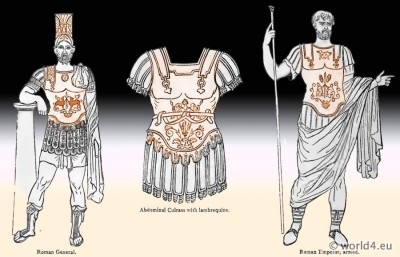

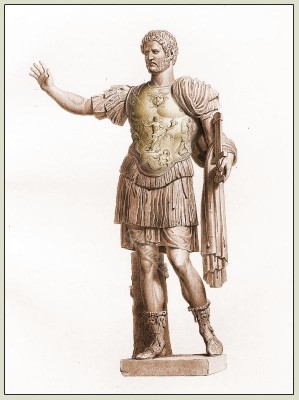

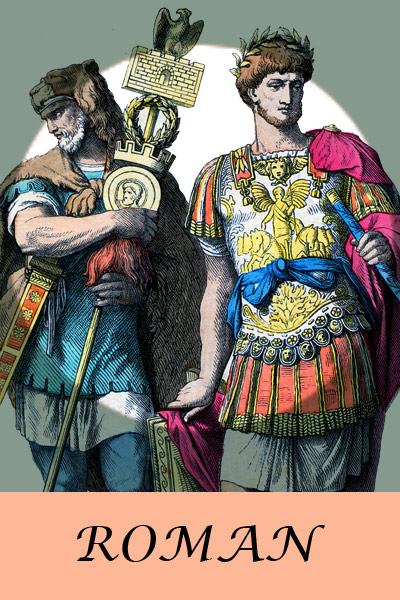

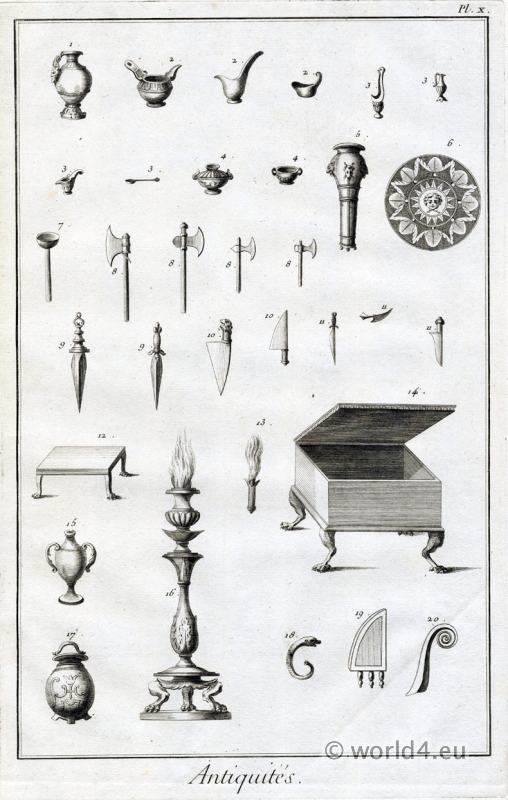

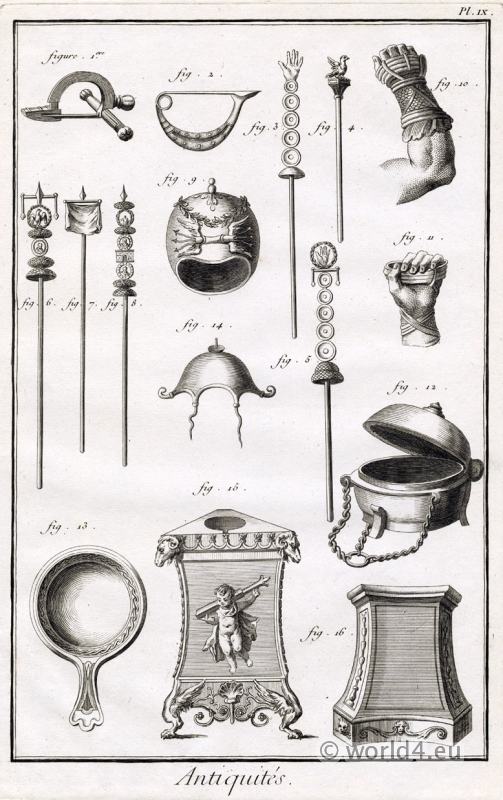

The armor of the Romans.

Roman armor derived from the Greeks and the Etruscans.

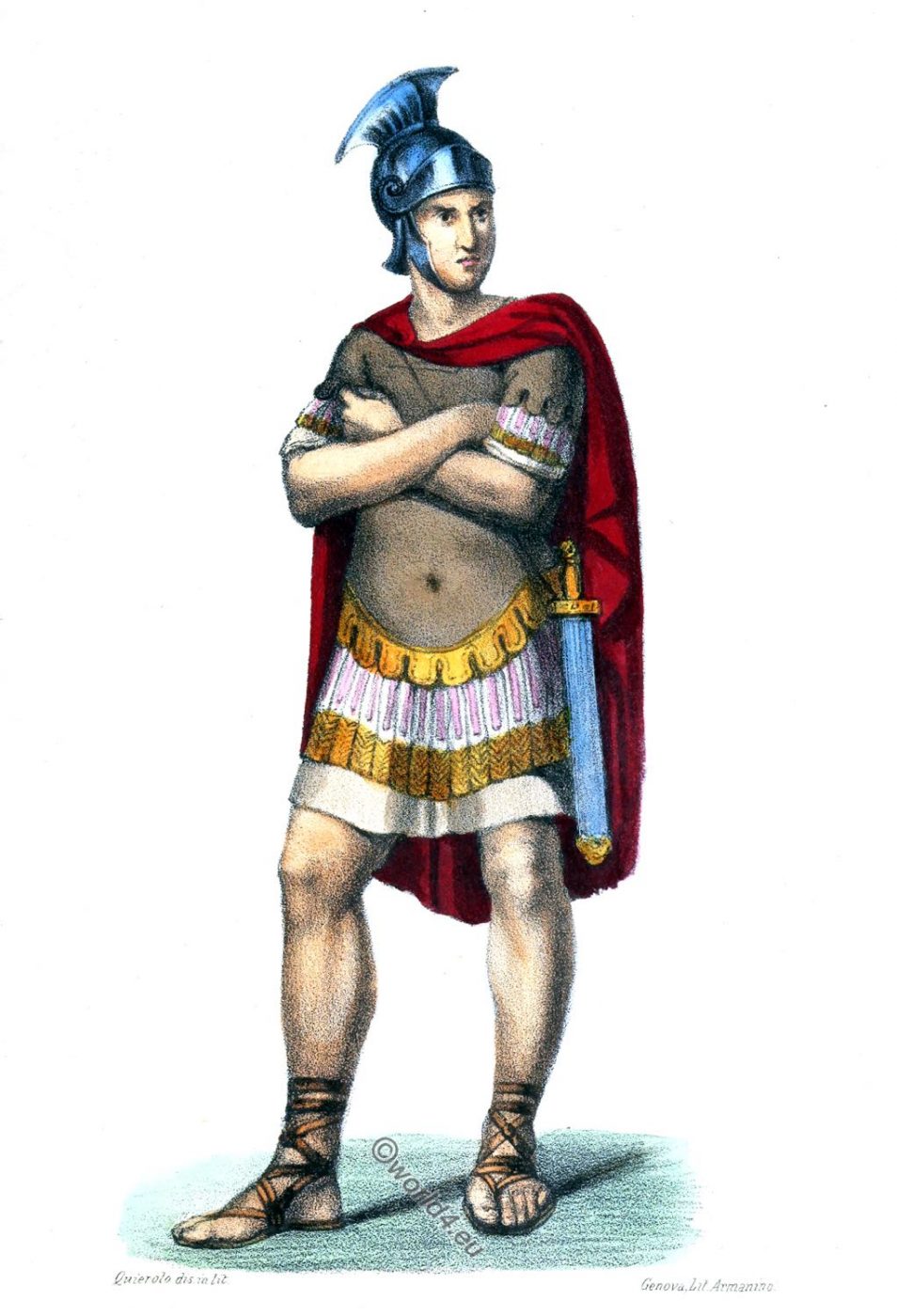

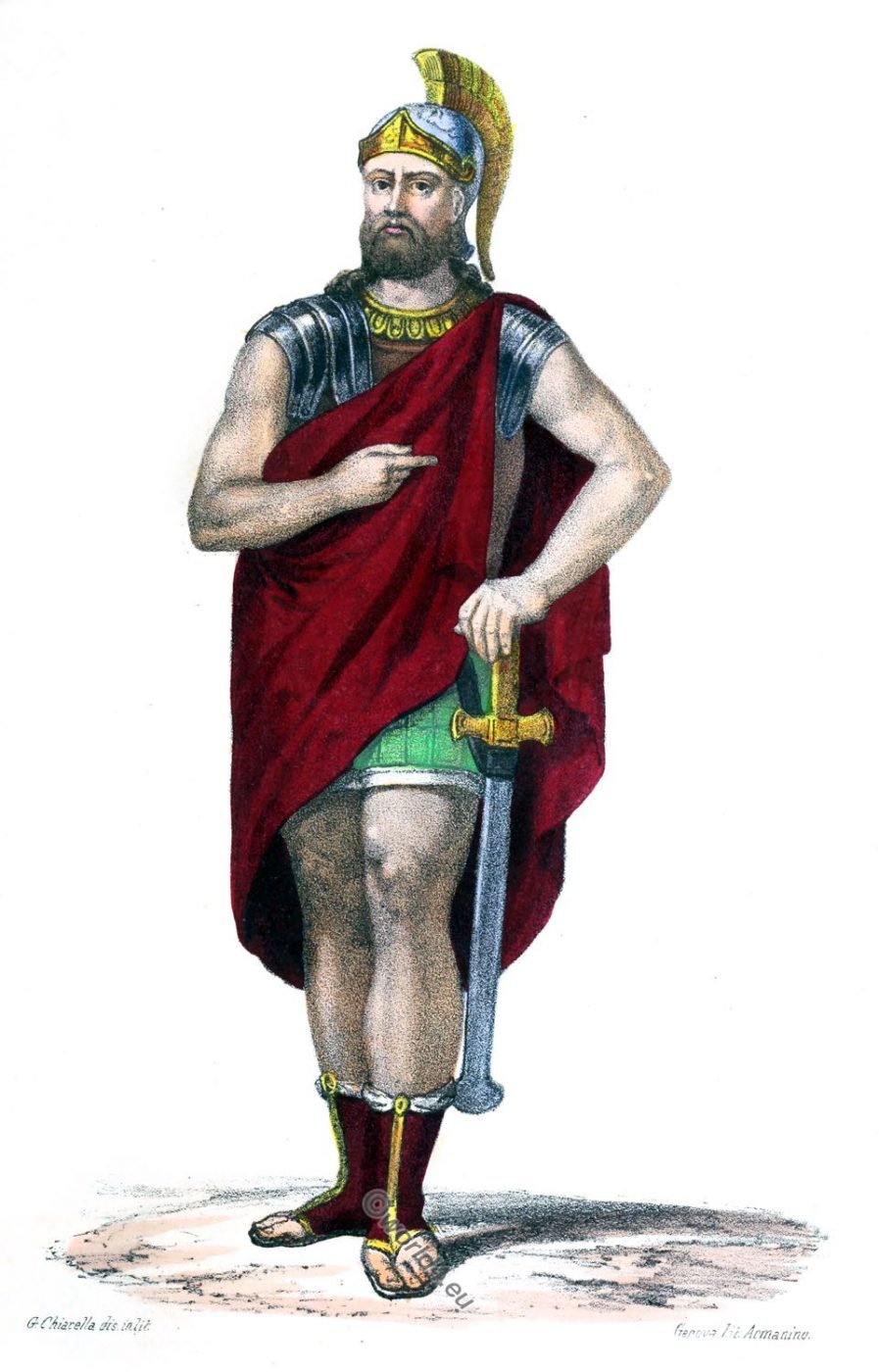

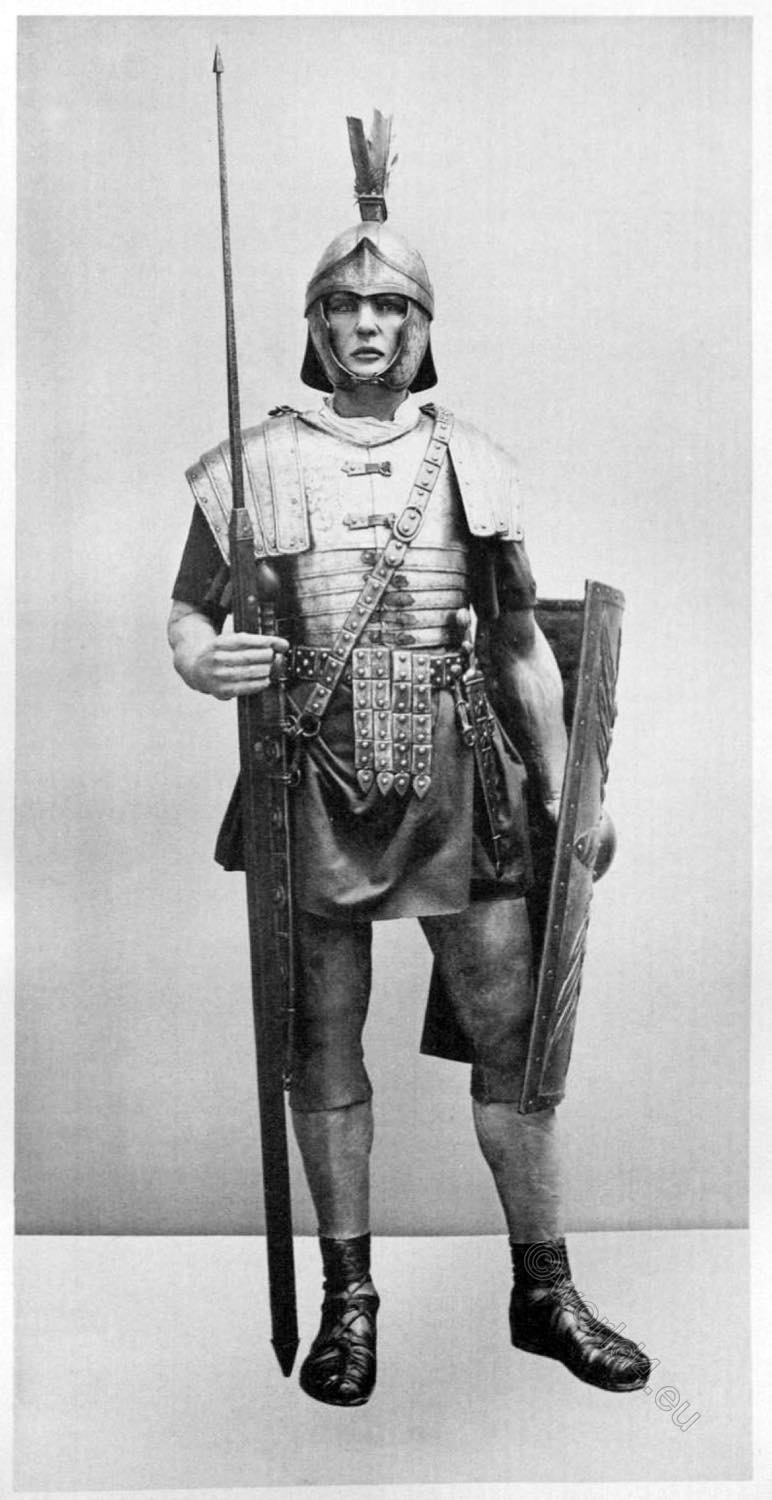

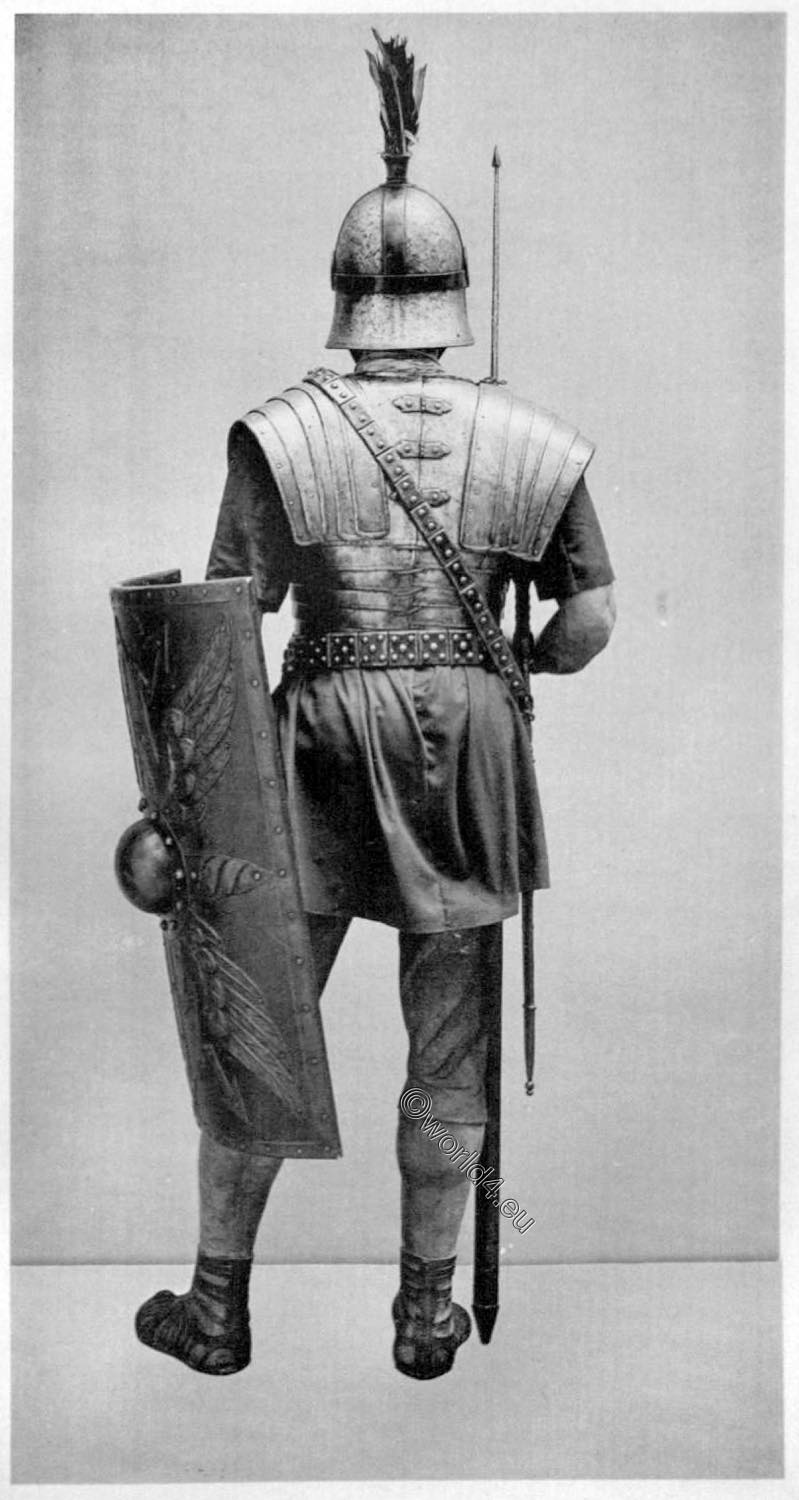

We must now turn to the armor of the Romans, derived from the Greeks and the Etruscans. Livy, speaking of Servius Tullius, tells us that “he armed the Romans with the galea, the clypeus, the ocreæ or greaves, and the lorica, all of brass” (“omnia ex ære”). This was the Etruscan armour, but in later times they substituted steel; for Silius Italicus says, “ferro circumdare pectus.”

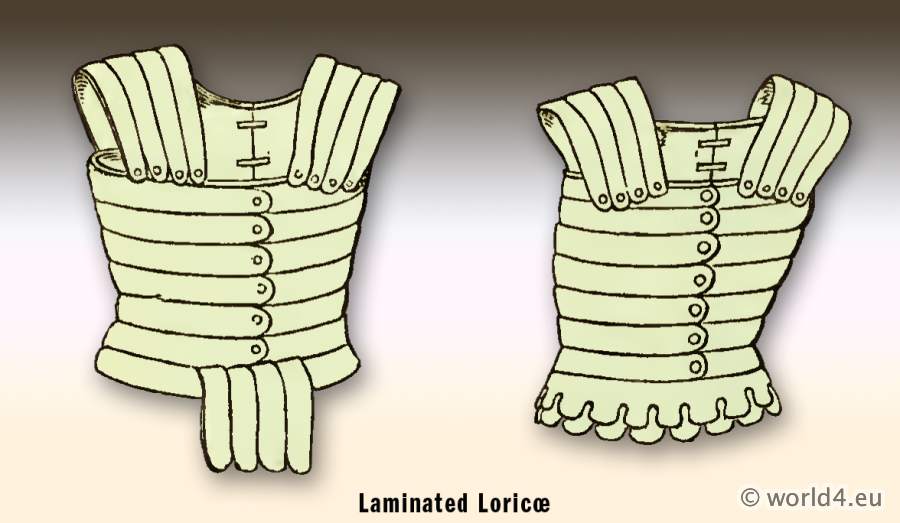

The lorica was a breast-plate, deriving its name, as did the modern cuirass, from its having been originally of leather, and in like manner retaining it when made of metal. It followed the line of the abdomen at the bottom, and seems to have been moulded to the human body. The square aperture for the throat was defended by a pectoral, also of brass; and the shoulders by pieces of the same metal, made to slip over each other.

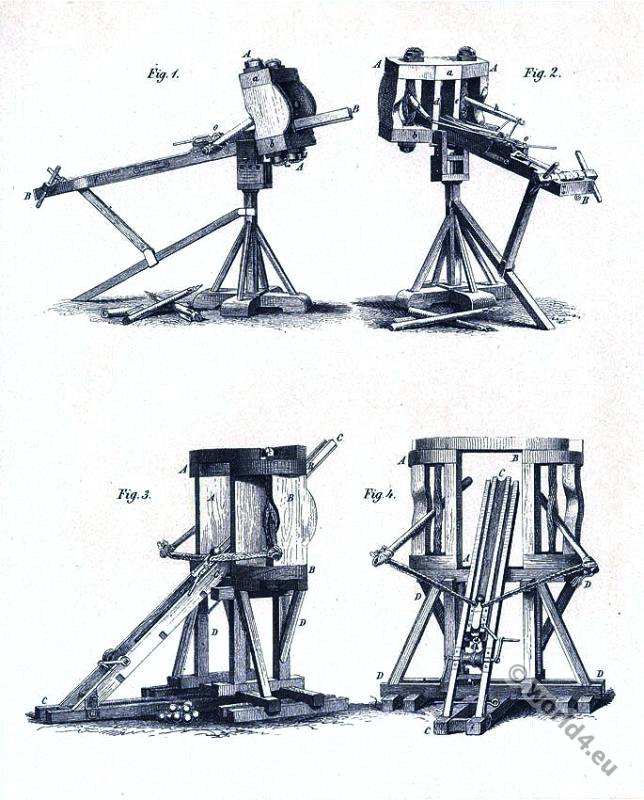

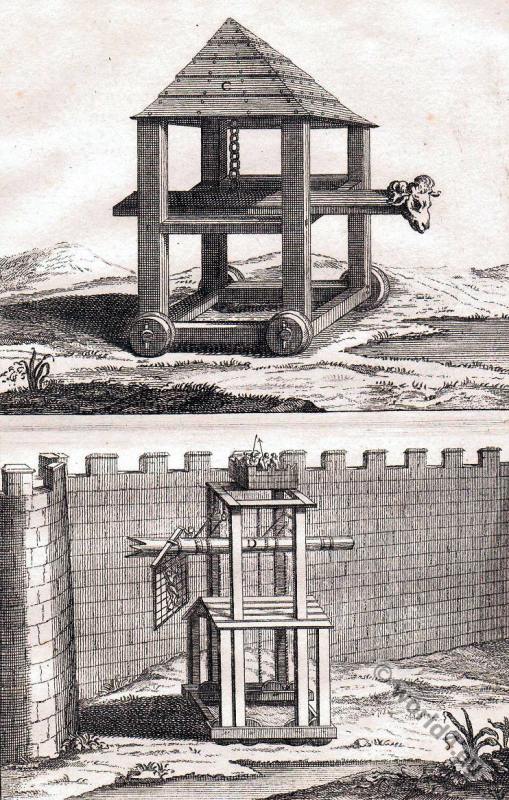

Above pictures – Roman Battering Ram, may relate to the campaigns of the Roman General Marcellus who led the siege of Syracuse between 214-212 BC. Original inscription: (C) BELIER COUVERT D’UN TOIT ET PORTE SUR DES ROULETTES (D) BELIER QU’ON ELEVOIT ET QU’ON ABBAISSOIT SELON LE BESOIN PAR LES FORCES MOUVANTES, OU PAR LE MOYEN DES CORDES ET DES POULES CONFORMEMENTA A LA ADESCRIPTION QUI EN A ESTE FAITTE PAR HERON. (Assaulting the walls of a fortification successfully is the key to taking any fortified position. This can be done using one or more of the following methods; battering through, scaling over the walls, or sapping to weaken the walls very foundation. A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare).

The earliest siege engine in Europe was the battering ram, followed by the catapult in ancient Greece. The first Mediterranean people to use advanced siege machinery were the Carthaginians, who used siege towers and battering rams against the Greek colonies of Sicily. These engines influenced the ruler of Syracuse, Dionisius I, who developed a large siege train. The Romans preferred to assault enemy walls building earthen ramps (agger) or simply escalading the walls, as in the early siege of the Samnite city of Silvium (306 BC). Soldiers working at the ramps were protected by shelters called vinea, that were arranged to form a long corridor. Wicker shields (plutei) were used to protect the front of the corridor during its construction. Sometimes the Romans used another engine resembling the Greek ditch-filling tortoise, called musculus (“Little mouse”). Battering rams were also widespread. Siege towers began to be used by the Roman legions from around 200 BC.

Some of these abdominal cuirasses were made of gold. One is said to be in the possession of the Count of Erbach, but I could not obtain any information about it when I visited the collection at Erbach. They were also enriched with embossed figures, Gorgons’ heads, thunderbolts, &c., and appended to them were several straps or flaps of leather, to which the French have given the name of lambrequins. They were fringed at the ends, and sometimes highly ornamented. In the time of Trajan the lorica was shortened and cut straight round above the hips, and, to supply the deficiency in length, two or three overlapping sets of lambrequins, as may be seen by the figures of generals on the Trajan Column.

Another sort of lorica was composed of several bands of brass, each wrapping half round the body, and being fastened before and behind, on a leathern or quilted tunic. In the British Museum, some of these brazen bands are preserved, and are about three inches wide. It is to this class of armour, when subsequently made of steel, that the above words of Silius Italicus allude.

These laminated loricæ were very heavy, and their weight was complained of by the soldiery in the time of the Emperor Galba.

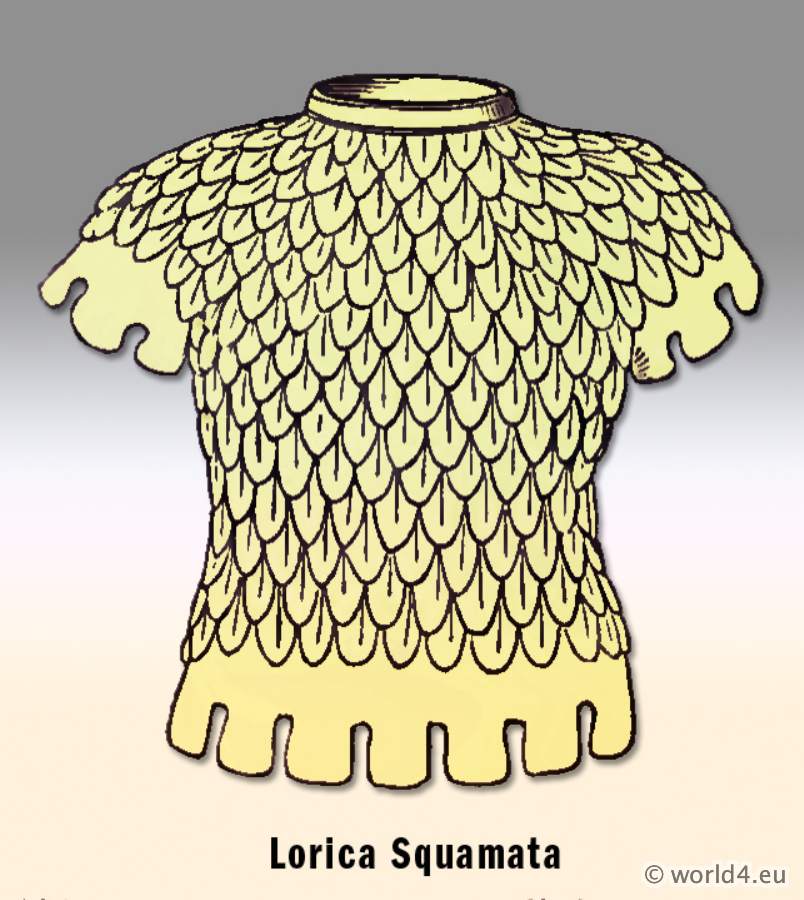

Other loricæ were composed of scales or leaves of brass or iron overlapping each other, and called squamata. This sort of armor had been adopted by the Romans from the Dacians or Sarmatians by the Emperor Domitian, who, according to Martial, had a lorica made of slices of boars’ hoofs stitched together; and Plutarch tells us that Lucullus wore a lorica made with pieces of iron, shaped like the scales of a fish.

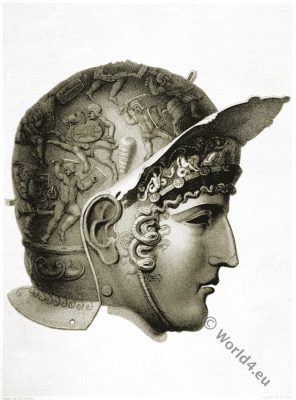

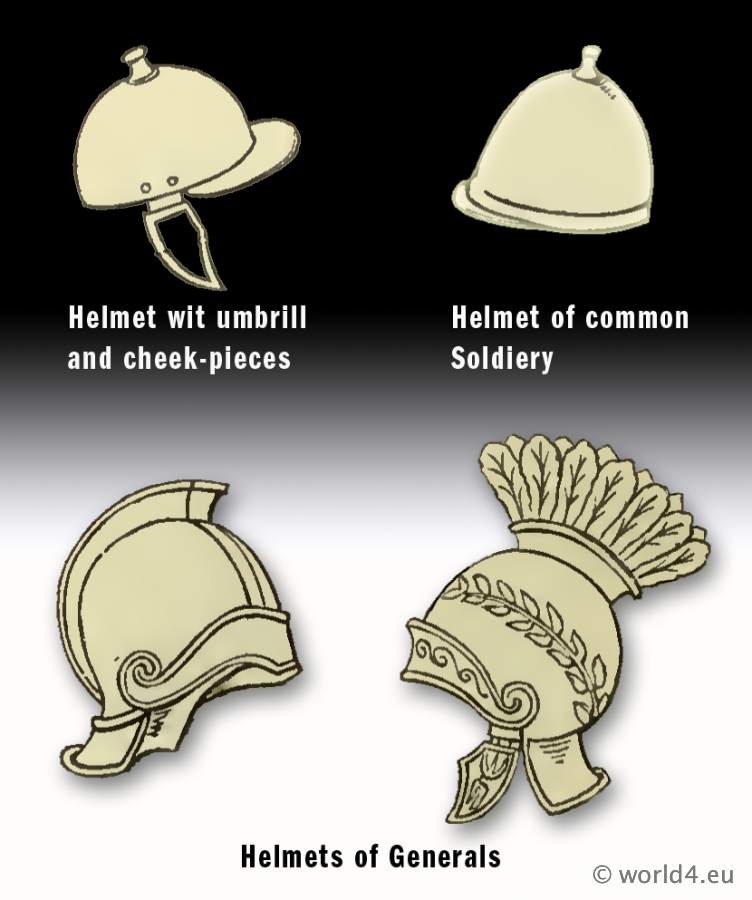

Roman helmets. The galea and the cassis

The Romans had two helmets, the galea and the cassis, the former being originally of leather, and the latter of metal; but the leathern head-piece seems to have fallen into disrepute in the days of Camillus, who, according to Polynæus, caused his soldiers to wear light helmets of brass, as a defence against the swords of the Gauls. After this time the terms galea and cassis were used indifferently. On the top of the helmets of the common soldiery is generally seen a round knot, and those of the infantry were furnished with umbrills and movable cheek-pieces, called bucculæ.

“Fracta de casside buccula pendens.” Juvenal, Sat. x., v. 134.

The helmets of the generals were of gold, surmounted by crests ornamented with feathers of various colours: “Cristaque tegit galea aurea rubra.” Virgil, Æ. ix., v. 49.

“The Roman shield,” Mr. Hope remarks, “seems never to have resembled the large, round buckler used by the Greeks, nor the crescent-shaped one peculiar to the Asiatics.” Its form was either an oblong square or an oval, a hexagon or an octagon, The cavalry alone wore a circular shield, but of small dimensions, called parma.

As offensive weapons, the Romans had a sword of somewhat greater length than that of the Greeks, in the earlier ages they were of bronze, but at the time of their invasion of Britain they were of steel; a long spear, of which they never quitted their hold; and a short javelin, which they used to throw to a distance. They had also in their armies archers and slingers.

The Roman foot gear

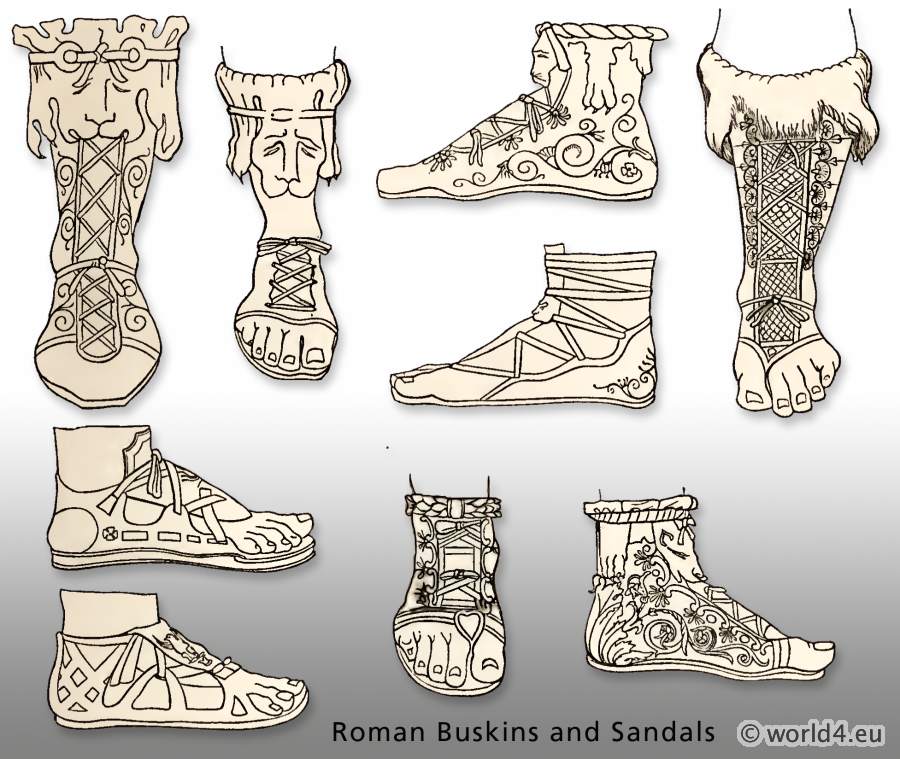

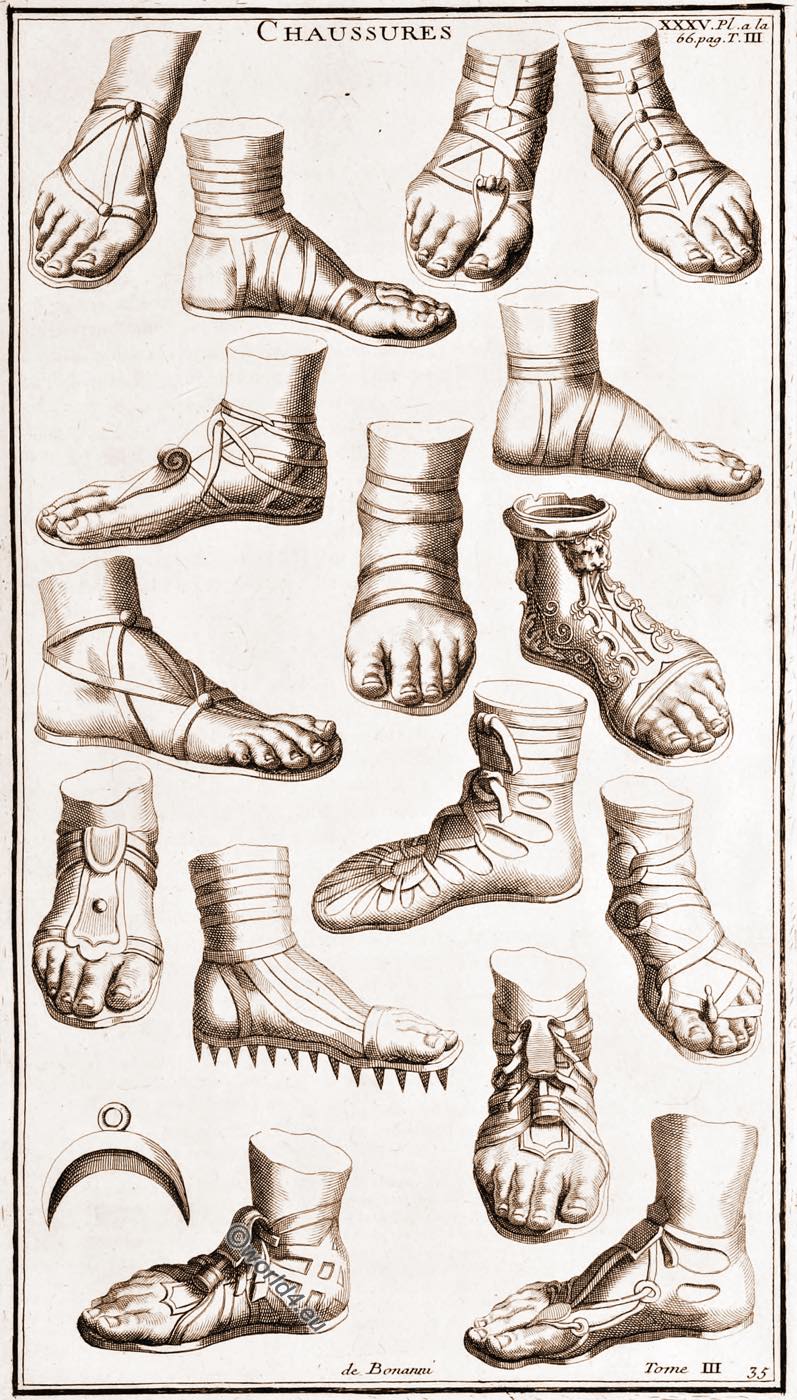

Of sandals and shoes the Romans had a variety, the greater portion copied from the Greeks; one sort covering the whole of the foot, and sometimes reaching to the middle of the leg, called ypodemata in the Greek, and in the Latin by several names, viz., calceus, mulleus, pero, and phæcasium.

Another kind covered the sole of the foot only, and were made fast to it by thongs of leather or of other materials. These were called by the Greeks pedita generally; but were variously denominated by the Romans caliga, campagus, solea, baxea, crepida, sandalium, and sicyonia. Occasionally the term calceus was applied to all. The mulleus was a shoe forbidden to be worn by the common people. Its colour was usually scarlet; but sometimes it was purple.

The phæcasium was a thin light shoe worn by the priests at Athens, and also used by the Romans. It was commonly made of white leather, and covered the whole of the foot. The pero, a shoe worn by the people of ancient Latium, was made of untanned leather, and in later times worn only by rustics and people of the lowest classes. The caliga and the campagus were sandals worn by the military. The sole of the former was large, sometimes strengthened with nails, and chiefly appropriated to the common soldiers, while the campagus was the sandal worn by the Emperors and generals of the army. It differed little in form from the caliga; but the ligatures were more often crossed over the foot and more closely interwoven with each other, producing a resemblance to network. The Emperor Gallienus wore the caligæ ornamented with jewels in preference to the campaign, which he contemptuously described as nothing but nets.

The solea, the crepida, and of course the sandalium, were all of them species of sandals fastened about the feet and ankles by fillets or thongs; but though probably each had its peculiarities, it is, as Mr. Strutt remarks, impossible at this distance of time to ascertain them.

The soleæ, we are told, might not in strict decorum be worn with the toga, and it was considered effeminate to appear with them in the streets of Rome. The Emperor Caligula, however, regardless of this rule, not only wore the solese in public, but permitted all who pleased to follow his example.

The baxea was also of the sandal kind, worn originally, according to Arnobius and Tertullian, by the Grecian philosophers, and, as it appears from the former author, manufactured from the leaves of the palm-tree. The baxeæ are noticed by Plautus, but nothing respecting their form is specified. The sicyonia, Cicero tells us, was used in races, and must therefore have been a very light kind of sandal. Lucian speaks of it as worn with white socks. There was a shoe or sandal called the gallica, being adopted from the Gauls, which was forbidden to be worn with the toga, and to these may be added the sanlponeæ worn by the country people, and the shoes with soles of wood (soleæ lignæ) used by the poor.

Two names, “familiar in our mouths as household words,” occur in the catalogue of Roman foot gear the sock and the buskin. The sock (soccus) is stated to have been a plain kind of shoe, sufficiently large to receive the foot with the caliga, crepida, or any other sort of shoe upon it.

The buskin (cothurnus) was anciently worn by the Phrygians and the Greeks, and derived its reputation from being introduced to the stage by Sophocles in his Tragedies. It was a boot laced up the front of the leg, in some instances covering the toes entirely; in others a strap passed between the great toe and the toe next to it connected the sole with the upper portion, which met together over the instep, and were from thence laced up the front like the half-boots worn at present.

Virgil thus alludes to them as worn by the Tyrian huntresses: “Virginibus Tyriis mos est gestare pharetrum Purpureoque alte suras vincire cothurno.” Æneid, lib. i. v. 336.

In Rome, as in Phrygia, the cothurnus was worn by both sexes; but, from the circumstance above mentioned, it has been specially associated with Tragedy. The soccus being worn by the comic actors, in like manner became typical of Comedy.

Socks or feet-coverings made of wool or goat’s hair, called udones, were used by the Romans, but it was considered effeminate for men to wear them. The shoes of the wealthy were not only painted with various colours, but often sumptuously adorned with gold, silver, and precious stones.

The Emperor Heliogabalus had his shoes set with diamonds interspersed with other jewels. The Emperor Aurelian disapproved of the painted shoes, which he considered too effeminate for men, and therefore he prohibited the use by them of the mullæi (which were red), and of white, yellow, and green shoes.

The latter he called “ivy-leaf coloured,” calcei hederacei. Sometimes the shoes had turned-up, pointed toes, which were called “bowed shoes,” calcei repandi, a fashion evidently derived from the East, and which was subsequently carried to such an extravagance in the Middle Ages. The senators, from the time of Caius Marius, are said to have worn black leathern boots reaching to the middle of the leg, a custom to which Horace is supposed to allude by the words: “Nam ut quisque insanus nigris medium impediit crus Pellibus.” Lib. i. Sat. 6, v. 27, 28.

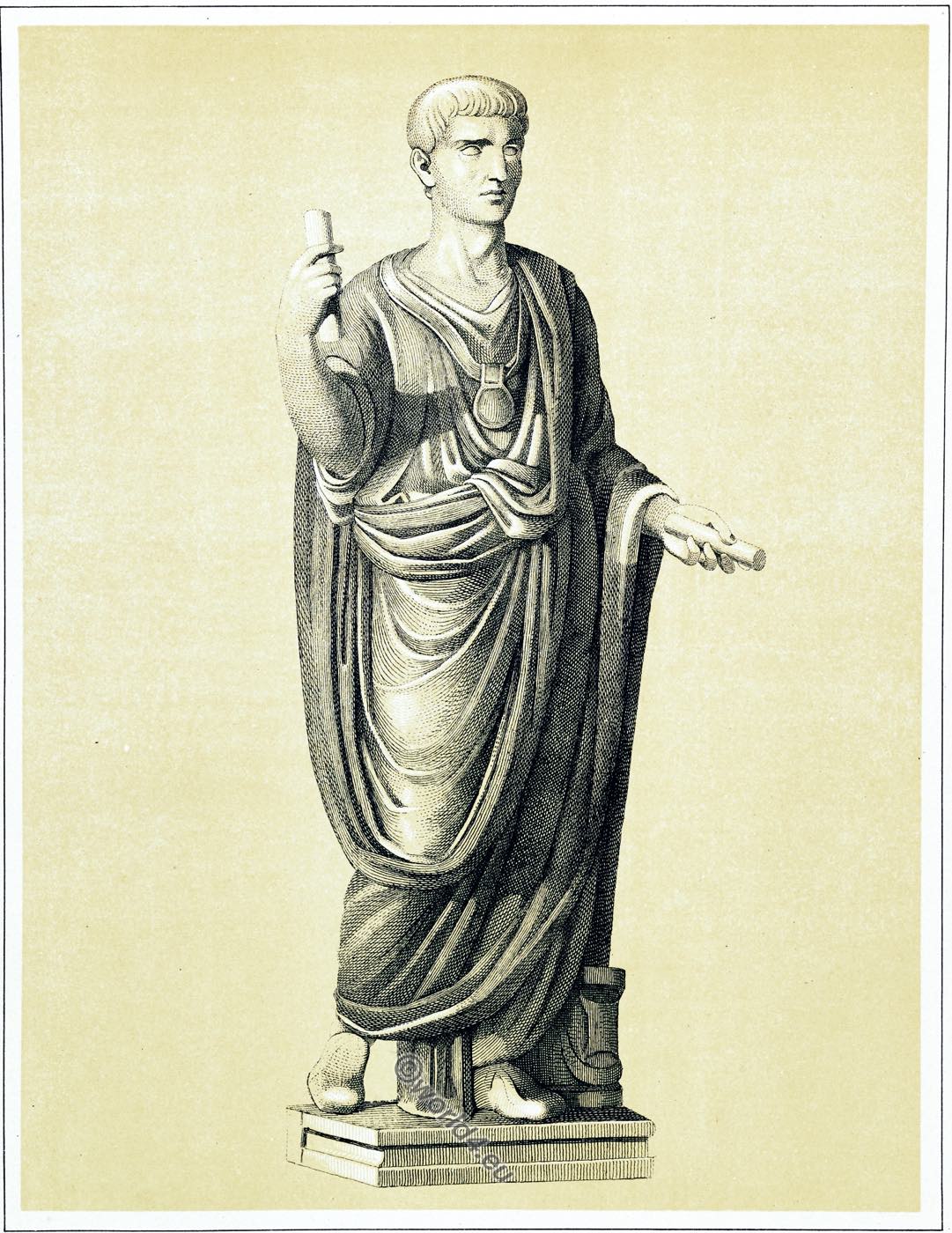

The Toga and the Tunic of the Romans.

The material of the toga was wool, the colour in early ages its own natural hue, a yellowish white, but later the undyed toga was retained by the higher orders; only inferior persons wearing them of different colours, while candidates for public offices bleached them by an artificial process. In times of mourning, a dark-coloured or black toga was worn, or it was left off altogether. Young men of noble birth wore a white toga edged with a purple border, and called the toga pretexta? until they attained the age of fifteen, when they assumed the toga pura, without a border. A toga striped with purple throughout, and called the trabea, was worn by the knights, and victorious generals in their triumphs were attired in togæ entirely of purple, which were in process of time made of silk and elaborately embroidered with gold. Such were denominated the toga picta or toga palmata. Varro in Nonius speaks of certain togaæ being so transparent that the tunics might be seen through them. There were also watered togæ, called by Pliny undulatæ vestes.

Among the ancient Romans the tunic was made of white woollen cloth and without sleeves, which were added to it afterwards, when it was called chiridota or tunica manicata. In general, the sleeves were loose and short, reaching only to the elbow, but their length and fashion seem to have depended on the fancy of their wearers, and in the time of the Emperors they were lengthened to the wrists and terminated with fringes or borders.

After the Romans had, in imitation of the later Greeks, introduced the wearing of two tunics, they used the words subuculum and indusium to designate the inner one, which, though the prototype of the modern shirt, was also woollen. Augustus is said to have worn in winter no less than four tunics beside the subucula or under-tunic, and all of them woollen. Montfaucon is of opinion that the interior garments of men were rarely if ever made of linen until a late period of the Roman Empire. Young men when they assumed the toga virilis, and women when they were married, received from their parents a tunic wrought in a particular manner, called tunica recta or regilla.

The tunic worn by the senators was distinguished by a broad stripe of purple sewed on the breast, and called latus clavus. Those who had not arrived at patrician honours wore a narrow stripe of the same colour, and therefore denominated angst clavus. Roman citizens whose means were insufficient to enable them to procure a toga, wore the tunic only, as did also foreigners, slaves, and gladiators.

The Roman women had several kinds of tunics, which are mentioned by Plautus, but unfortunately without any description. The impluviata and the mendicula were tunics, but their colour, form, and texture are totally unknown. The ralla (which is thought to be the same as the rara) and the spissa differed much from each other in texture, the first being of a thinner and looser texture than the latter. They had also a tunic called crocotula, the diminutive of crocota, which was an upper garment in use amongst the Grecian females, and received its name, Montfaucon says, from crocus, saffron colour, or from croce, the woof of any texture.

The belt or girdle was a necessary appendage to the tunic, and was made of various materials and ornaments, according to the rank or circumstances of the owner. It was not customary with the Romans to wear it at home, but no person appeared abroad without it, and it was thought effeminate and indecorous to appear uncinctured in the streets. The Roman women, married as well as unmarried, used girdles, which are occasionally concealed by the upper portion of the tunic falling over them.

Source:

- A cyclopedia of costume, or, dictionary of dress, including notices of contemporaneous fashions on the continent; a general chronological history of the costumes of the principal countries of Europe, from the commencement of the Christian era to the accession of George the Third, by James Robinson Planché. London Chatto and Windus 1876-79.

- L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures by Bernard de Montfaucon. Paris: Chez Florentin Delaulne, 1719.

- History of Costume in Chronological Development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Published by Firmin-Didot et cie. Paris, 1888.

Continuing