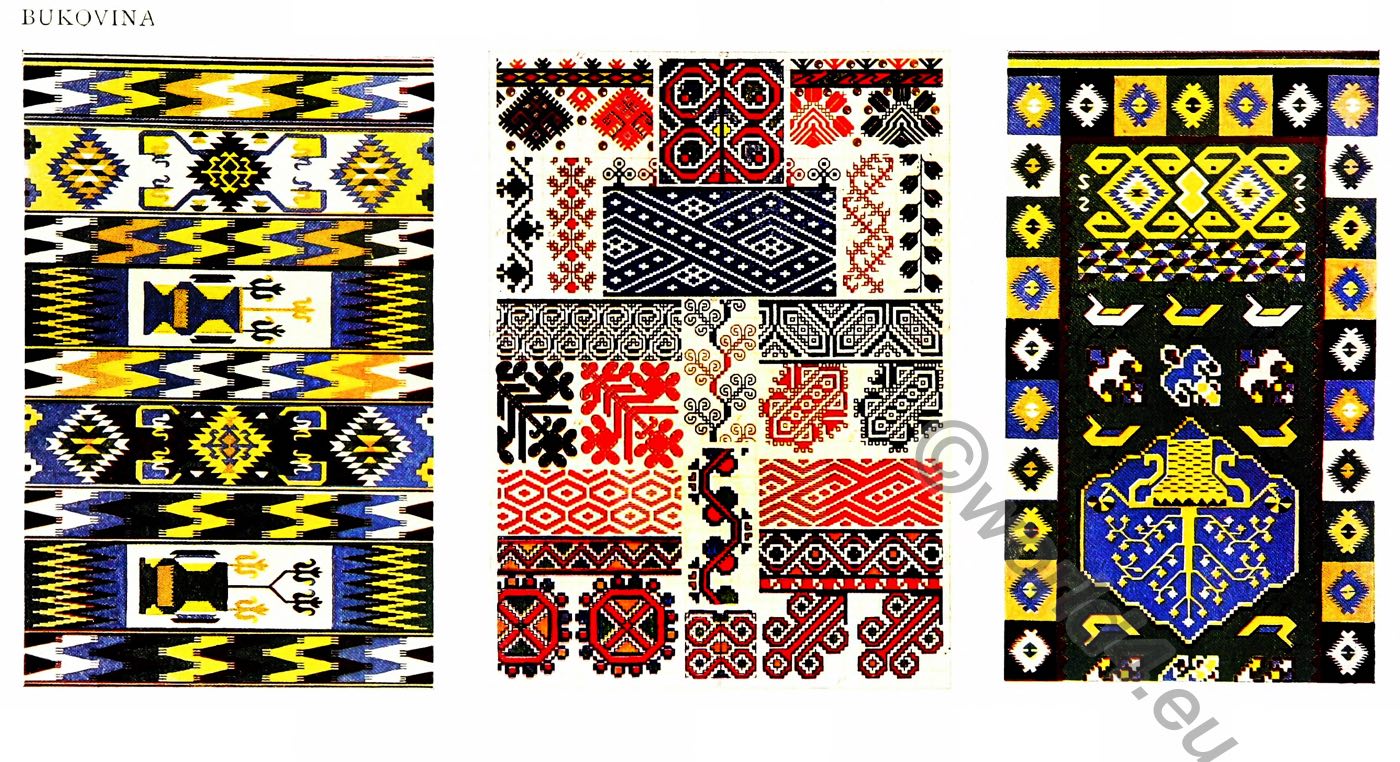

CARPETS FROM TÜRKEY.

TÜRKEY forwarded to the Exhibition of 1862 a large contribution of carpets of every description, which, whether for richness and harmony of colour, good design, and excellent make, fully sustained the reputation which that country has so long held for woven fabrics. There were upwards of forty-six exhibitors in this class (22); and prize medals were awarded collectively to the manufacturers of Phillipopoli, Salonica, Saroukhan, and Ushak.

The large woolen carpets, which have been in such repute for centuries, known generally as Smyrna carpets, are not made in that city, but exported thence only, from the principal seats of the manufacture, Saroukhan and Ushak.

These more nearly resemble the best Indian carpets, and formed the models on which our own Axminster and other carpets in the 18th century were made: rich and deep in colour, the pattern being mostly lost in the general effect, they differ materially in style from those which we have selected for illustration, which are characterized by more thoroughly national patterns, in which the zigzag designs, and bold yet well-arranged colours, are very striking.

They are made by nomad tribes throughout the empire, the women mostly working on them in winter, when not occupied in their agricultural or pastoral pursuits. M. Gadben, who was indefatigable in his duties as superintendent of the Turkish court, and to whom we are indebted for much useful information, states that a carpet 18 feet by 4 feet 6 inches would sell on the spot at about £8. They are generally made of wool, or sometimes of wool and cotton mixed. However much the carpets of India, Turkey, Persia, and North Africa may differ in quality, they are all produced by the same simple and ancient method, forming work which for beauty, durability, and even mechanical perfection, has never been surpassed. The loom in which these carpets are made consists of two wooden standards, or planks, placed at some distance apart, which support a roller at the top, upon which the warp is wound; and about two feet from the floor is placed another roller, round which the carpet is turned as it is made.

The work is done entirely by hand, and each tie passes across the face of two warp-threads round the back, and has the ends drawn up between them. When a row of ties has been completed, a shed is formed in the warp, and the shoot is then passed from right to left, and returned, binding the whole together, and is then beaten down to a horizontal level by hand-beaters. Plain carpets are thus made in one piece of the largest dimensions. The number of colours that can be used is unlimited, and any design can be copied with great accuracy. The most costly and magnificent carpets of Europe are made upon the same principle as the above; such as the splendid productions of the Gobelins; those of Tournay, in Belgium; Deventer, in the Netherlands; Aubusson, France; Wilton, and the old Axminster carpets. (Official Report, Class 19, 1851.)

The introduction of Turkey carpets in Europe is of very early date. In De Barente’s “Dukes of Burgundy” mention is made, A.D. 1898, of “twelve velvety carpets of the country of Turkey, ten of which are small, and two of medium size.” In the inventory of the Queen Clémence, A.D. 1328, the “tapis velu d’outremer,” and “tapis velu de Rommenie” (Roumelia), are doubtless Turkey carpets. M. De Laborde states that “oultremer” means always the Levant; and in Rommenie, or Roumelia, are included all those provinces wrested by the Turks from the Western empire, where the Roman language had been in vogue. Archbishop Parker, A.D. 1575, possessed a Turkey carpet for the presence-chamber, five yards long by 2f yards broad, valued at £3. In the inventory of Hengrave Hall, A.D. 1603, carpets of Turkey-work occur frequently.

Turkey carpets placed before the communion-table are frequently mentioned in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. It is stated in the second volume of Hakluyt’s Voyages, that Morgan Hubbelthorne, a dyer, was sent to Persia, at the expense of the city of London, to learn the arts of dyeing and making carpets, as practiced there. In Beaumont and Fletcher’s comedy of the “Coxcomb,” written about this period, we find: “Take care my house be handsome, flowers for the window; and the Turkey carpet.” Barnaby Goodge, in his English version of Naogeorgus, writes, “and upon Turkey carpets lay him downe full tenderly.” In 1660 Turkey carpets are advertised for sale; and at this period our commerce with the East had become so extended as to render them much less rare.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the Levant or Turkey Company, which was incorporated in the year 1581, traded in these carpets. The East-India Company also imported “rich carpets of Persia and Cambaya;” and Oriental carpets formed the models of all the earliest manufactures in this country (England).

Source: Masterpieces of industrial art & sculpture at the International exhibition, 1862 by John Burley Waring. London, Day & son, 1863.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.