Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, dame Le Normant d’Étiolles, marquise de Pompadour, duchesse de Menars (born December 29, 1721 Paris; † April 15, 1764 in Versailles), short Madame de Pompadour, was a mistress of the French King Louis XV.

WHEN we turn our minds to the Rococo period we seem to see a magic land of dazzling, exquisite beauty. We who live in this bustling, mechanical, machine-ridden age cannot but be seized with a feeling of envy for those who lived in that pleasant period, a period which seems to have been devoted entirely to the enjoyment of life.

Charming, coquettish women, elegant, gallant men lived (or so we imagine) in this paradise, without any cares but those of the body, and without any troubles but those of the heart. Happy people perpetually gathered on smooth, cultivated lawns, as in the pictures of Watteau, and making ready to embark for Cythera. Indeed, the wealthy classes, in France at least, did live on a kind of enchanted island, where the only employment was the pursuit of pleasure and the only goddess the Goddess of Love. And their island was not far away in some uncharted sea, but at hand, at home—the Ile de France!

The mere phrase dix-huitième siècle conjures up a vision of a veritable paradise on earth; and no matter how far such a picture may be from reality, it has imposed itself ineffaceably upon the imagination of the world.

Those courtly gallants, their velvet and silk clothes bedecked with diamonds, feathers, and gold, and those ethereal ladies, in mythological costumes, in charmingly seductive negligés, in piquant deshabille’s, seem to have lived solely for enjoyment and sensuality. They are themselves mythological, and for them life had no burdens, no pains, no sorrows, but was one perpetual fairy-tale of pastoral pleasures, of voluptuous dances, of country picnics, of brilliant balls, and of gallant adventures.

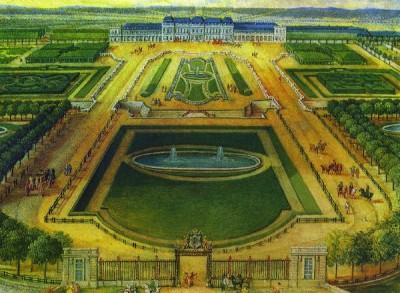

The Rococo men and women lived in rich palaces with boudoirs built for coquetry; they walked in splendid parks with alleys planned for assignation; they slept in soft, silk beds that had been made for love. In short, they had but one aim — to enjoy life, and, in retrospect at least, they seem to have succeeded.

The Rococo period, which stretches from the death of Louis XIV to the accession of Louis XVI, was one long hymn of praise to pagan love, an endless glorification of the pleasures of the senses, an unceasing incense offered at the shrine of woman. And women themselves were as eager as men to take advantage of the prevailing laxity of morals.

The most typical representative of the elegant and gallant women of the period was Mme de Pompadour, whose name is inalienably associated with the epithet Rococo. The long reign of this extremely clever courtesan was the Golden Age of elegance, fashion, frivolity, and light-heartedness, but no less of the fine arts.

No other mistress of a king, and indeed very few of her sex at all, has possessed the Pompadour’s fine creative taste, coupled as it was with a fertile imagination and no mean talents. Her whole personality bore the stamp of the elegance of the period.

She was a born voluptuary who shrank from no gratification of her desires; and when she became the mistress of the pleasure-seeking King, and could dip at will into the State coffers and the private purse of Louis XV, her passion for spending knew no bounds. But so creative was the mind of the Pompadour that she has left her mark on everything she touched.

Before the king left Versailles for his army in Flanders, the keen eye of Madame de Chateauroux had noticed a singularly beautiful woman who always placed herself in the path of Louis XV. whenever he hunted in the forest of Senart. The instinct of jealousy led her to suspect in this unknown lady (for she did not belong to the court) a future rival.

Her surmise was correct; and, when the king’s grief for her loss was somewhat abated, Madame de Chateauroux was succeeded in the post of royal favourite by the intriguing Madame le Normand d’Etiolles, better known as Madame de Pompadour. It is astonishing how often in the surviving literature of the period the name of Pompadour recurs, associated with some work of art or some product of the age.

Even to-day a small lady’s bag is known by the name of Louis XV’s favorite. It is true that no small part of her influence was due to the flunkyism and snobbery of the Court, which delighted to use the name of the different mistresses of the King to add glamour and attraction to every object of luxury. Parisians, more than the citizens of any other capital, are prone to make an idol of the hew and fashionable; Casanova observed this characteristic on his first visit to Paris. He expressed his surprise to a friend that one particular snuff- shop was besieged, and that everybody insisted on buying snuff there and there only.

It was not because the snuff there was better than anywhere else, but because a woman of fashion, the Duchesse de Chartres, had made the shop fashionable, by the simple process of ordering her carriage to be pulled up there once or twice to have her snuff-box filled.

Every snuff-taker in Paris crowded into the shop to follow her example, and the lucky tradesman made a fortune. But it was not mere snobbery which brought everything the Pompadour adopted into fashion. This woman possessed a gift which is to be found not only among ladies of high rank or of any particular culture, but as often among women and girls in a very simple station—the gift of choosing her own clothing and furniture with singularly good taste.

In her hands a mere nothing became a work of art. A little piece of material or a ribbon was sufficient to make a ravishing bow, placed in the very spot where it would be most attractive. This enchantress of good taste laid a spell on all her contemporaries. The time came when everything the Marquise approved of was designated à la Pompadour.

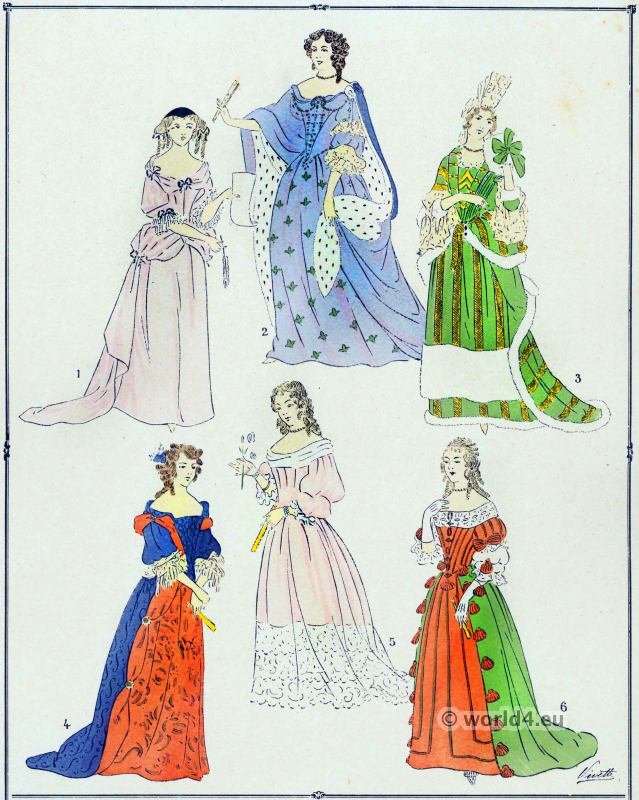

She was, herself, not the slave of fashion, but its queen. Her clothes were not mere fashionable caprices, but the very patterns of real elegance and good taste. Every toilette she wore was her own creation; and it was not only by the splendor and extravagance of her costumes that she commanded admiration, but by her ability to adapt any fashion to her own individuality. She seldom allowed vanity to carry her away, and never strove to make an effect by wearing some dress which might be the fashion but which did not suit her.

She was always herself, always new, always creative. She appeared at the King’s levees, to which all the courtiers were admitted, in a fascinating morning robe of her own invention, which set off to perfection the lines of her charming figure—and soon everybody wore déshabillé à la Pompadour, Negligés were, in the eighteenth century, adopted frankly as instruments of seduction, and Mme de Pompadour and her elegant contemporaries expended the utmost care on these seemingly careless toilettes.

The delicacy and care which went to the making of these negligés can be gathered from the many descriptions which have come down to us of the levees of aristocratic ladies and of famous courtesans.

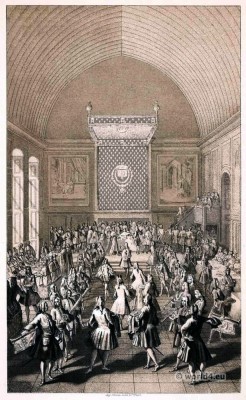

The toilet of a woman of fashion was an elaborate business, occupying the greater part of her day. But as women wanted to see something of their friends, they invited them to be present at their levees, and by their company help to while away the long hours at the dressing-table.

Moreover, the custom gave the elegant woman an excellent opportunity for displaying her charms, one by one, to her admirers; and this public toilet of the eighteenth century was fashionable in high society even in comparatively prudish England. At the levees of a great number of the influential ladies of the Court and of famous courtesans, such as the Pompadour and her predecessors, the talk was often political.

They were attended by ministers, councillors, and foreign ambassadors. The young General Wolfe visited the King’s mistress at her toilet-table and discussed the situation in Canada. At other times the conversation would be of the latest products of literature and art. But as a rule the levees were given over to gallantry and love-making.

Frequent flirtations took place, not always confined to words and glances. The tone of the levee varied with the temperament of the lady and her friends, and while some were merely frivolous, others were frankly sensual. The Pompadour was one of the cleverest women of her time, and readily produced whatever atmosphere she desired.

At her levees she was capable of advising ministers, disposing of high diplomatic posts, and sending out lettres de cachet from her boudoir, while all the time inflaming the senses of the King and her other admirers. She loved to prolong her levees as much as possible, trying on every imaginable negligé, Court dress, shoe, slipper, stocking, and garter.

Every physical charm was brought into play in turn, for she was a true child of her period, and professed the cult of her own beauty. Her shoulders, her arms— she had beautifully shaped arms, which even drew comment from Marie Leszczynska— her neck, her enchanting little foot, her slim legs— each physical perfection added to the desired effect. Powder made her skin like marble, robbing it of the warm, bright colors of life; so she wore very little.

To have her hair dressed she would sit in a cloud of fragrant lace; then, with a sudden gesture, she would throw everything on one side, and swathe her limbs in some new enhancement of her beauty.

The eyes of the men rested in admiration, and those of the few women present in curiosity, on this capricious ruler of elegance; but every woman observed carefully all the details of her clothes in order to copy them, until at last there was scarcely a single object, not a garment, not a piece of furniture, that was not à la Pompadour.

Toilet requisites, ribbons, fans, bags, dresses, cloaks, carriages, tables, chairs, beds, cupboards, table utensils, even tooth-picks, bore her name. A woman could have no pretensions to chic unless her clothes were à la Pompadour, her furniture à la Pompadour, unless she drove, rode, conversed, and occupied herself à la Pompadour.

François-Hubert Drouais (1727-75)

It was not only the furniture of her salon, her boudoir, and her bedroom which set the fashion—the tone that prevailed in her rooms was imitated too. For to the ladies of the Rococo period the most important rooms in the house were the intimate rooms: the bedroom and the dressing-room.

At that time, when marriage in the higher classes of society was often a mere pretense, when the whole life of the woman of fashion was given up to flirtation and sensuality, the bedrooms of married couples were naturally placed as far apart as possible, not in order to preserve the freshness of married life, but to allow the partners freedom to pursue their adventures. A husband who asked to share his wife’s bedroom would have been laughed at. He was not even present at his wife’s levee.

In the first place, he was usually engaged elsewhere; in the second place, his presence would have been a disturbing element. The taste of the period did not require that one should be home-loving and respectable—still less was it desirable to seem so. Even the privileges of a lover were strictly limited by his mistress, for eighteenth-century ladies liked variety. Even the gallant Duc de Lauzun, who was a great favorite with ladies, did not succeed in establishing a monopoly.

He was deeply hurt when the beautiful Lady Barrymore, who lived for a time at the French Court, persisted in sharing her favors with him and with the young Comte d’Artois.

When Lauzun found he had been betrayed and began to upbraid her she replied in the real Rococo spirit: “You are wrong to give me up, Lauzun. I like you. You appeal to my taste. I love you very much, but I love my freedom more dearly even than you. I will not sacrifice myself to your ill-temper, nor allow my lover to be as jealous, peevish, and obstinate as a husband. . . . Do not let us quarrel about so unimportant a matter, Lauzun.” And as he kissed her she whispered: “I will not make any sacrifices. I shall keep both the Comte d’Artois and you.”

Such was the eighteenth-century woman’s attitude to love. It goes without saying that these women furnished their bedrooms, in which they spent most of the day, with the utmost artistry and luxury.

Their first concern was the bed. It occupied the greatest space in the room, and the greatest care was lavished upon it as the veritable temple of love. In the words of Curt Moreck *), it was “the spirit of voluptuousness which, as though by magic, created in the bedroom of the eighteenth-century lady, out of delicate woodwork and a cloud of silk, lace, and ostrich feathers, the shell-like bed of love, placing a mirror in the draperies at the back and in the ceiling of the canopy,” so that the beauty of the sleeper might be multiplied.

Of all the painters of the period it was Fragonard who depicted most successfully the seductive grace of the woman in bed, and from the vogue of his pictures we can guess the leading part that was played in the love life of the eighteenth century by this most intimate of all articles of furniture, and the personal charm which the women even of the bourgeoisie were able to give to their bed- rooms. How much more important it must have been for the declared courtesans and the frivolous ladies of the Court and of high society to make of their bedrooms a seductive frame for their half-naked beauty. Mme de Pompadour was past mistress in this art.

*) Konrad Haemmerling was a German writer. (1888-1957). Pseudonyms: Arbiter Novus, Konrad von Köln, Konrad Merling, Curt Moreck, Kurt Moreck, Beatus Rhein, Kurt Romer, Sigbert Romer. In 1933 his works fell victim to National Socialist bans; his publication possibilities were severely restricted during the Third Reich.

To her great disappointment, however, she had early to experience the growing indifference of the King. In spite of everything, when scarcely a year had passed, he ceased to find with her any physical pleasure.

The rumour began to spread at Court that she would soon be sent away, that the King was bored even with her. She trembled at the thought that she would have to forfeit, so early in her career, her position, so hardly won, of maîtresse en titre, and all the glamour and wealth that accompanied it.

She blamed her temperament, for she was by nature cold, and had always had to force her- self to fulfill the duties of a lover. She had never been sensual she had always been ambitious.

She would have preferred to do as Marie Leszczynska did, and bolt her door when the King came and knocked at night; but she was no queen by right, and every day she pondered all possible means of adapting her physical temperament to that of the King.

The fear of losing him altogether drove her to the use of aphrodisiacs. At first she only had her food very highly seasoned. At breakfast she drank several cups of vanilla chocolate, flavored with ambergris.

At midday she ate highly seasoned soups and a quantity of truffles, and finally, in despair, she took a so called love-potion prescribed by some quack. In this respect also she was a true child of her period, and believed, as did every one else, in magic cures and secret medicines, unmindful of the bad effect on her health which they were bound to have.

The taking of love-potions and love-pills was an almost universal practice among these creatures of pleasure, for their chief object was to keep themselves as long as possible in a state of erotic excitement. Particularly favoured were the very dangerous aphrodisiac poisons, such as cantharides (Spanish fly), which was mixed in food or eaten in the form of sweetmeats. The perpetual round of new adventures, the endless nights devoted to passion, the little time which their life left them in which to recuperate, made recourse to such drugs almost inevitable.

It follows naturally that stimulating dainties of all kinds were among the favorite dishes at an eighteenth-century dinner-table, particularly oysters, fish, crabs, artichokes, truffles, turtles, and highly spiced ragouts, and there was no lack of these dainties at the banquets of Louis XIV and Louis XV. As many as eighty courses were sometimes served at a single meal, and these were prepared with all the delicacy of the finest culinary art. Yet even the addition of the choicest wines did not supply the necessary stimulus for the senses, and the unfortunate creatures of pleasure were compelled to resort to secret medicines and to love-potions.

It is hardly necessary to remark that the chief benefit from these elixirs was reaped by their inventors and retailers. Certainly Mme de Pompadour’s passion was not enhanced thereby. She remained passive and cold, and the King consoled himself— with the complaisant assistance of his favorite—with young girls brought to a house in the deer park.

The Pompadour was as superstitious as all the other ladies of the eighteenth century, and as ready as they to fall into the hands of quacks. Casanova has left an entertaining account of the frauds he practiced both in Venice and in Paris, and of how he imposed not only on the ignorant, but on the equally credulous grand ladies of the Court who came to him for assistance. And Casanova was an amateur in quackery compared with Cagliostro and others like him.

But neither magic cures, nor elixirs, nor the skill of Casanova availed the Pompadour, and the most charming, the most beautiful, and the most accomplished woman in France had very early to learn the lesson of the transitoriness of all beauty.

At the age of thirty-five her complexion, once so dazzling, was pale and faded. Her charming figure, the tender curves of her breasts and shoulders, had fallen away and become angular, and she had to use the strongest cosmetics in order to hide the wrinkles and blemishes with which premature age was disfiguring her face.

The common French practice of using rouge and powder was very convenient for her, but she seems to have carried its use too far, for contemporary chronicles say that it was almost impossible to recognize her features under the thick layer of rouge.

One keen observer of the manners of the period wrote that at the Court of Louis XV, when Mme Pompadour was the leader of fashion, the “stupid habit of rouging” had produced such a ridiculous similarity between the ladies that it was difficult to distinguish one from another. So bright was the red on their cheeks that they might have been taken for furies on the point of executing a wild dance. “And,” continues this severe critic, “they did not only obliterate their features by this means, but they quenched every feeling of desire in men, whose one wish was to flee from them.”

This opinion, however, does not seem to have been shared by all men, for most of these painted ladies had the greatest success, and certainly could not complain that their admirers avoided them. Casanova too was of opinion that at the time of Louis XV the ladies of the Court used rather too much rouge, but he liked it. He writes: The charm of these painted faces lies in the carelessness with which the ladies redden their cheeks. They have no wish that the color should seem natural. It is put on to please the eye, for it gives an illusion of sensual excitement which promises unusual pleasure amid positive orgies of love.

In violent contrast to the flaming red cheeks was the dead white of the rest of the face, enhanced by the blackness of the patches worn by women through out the century. The passion for ‘make-up’ was universal, and in no century was so much powder and rouge used as in the eighteenth.

Men, as well as women and children, applied it to their faces, as if by its use they might put a check on advancing years. Women had succeeded in abolishing time, for the powdering of the hair by young and old alike obliterated the differences of age. Many a woman was more successful than the Pompadour in reducing her apparent age at least ten years by means of cosmetics, but perhaps the Marquise, in her anxiety to keep her fading youth, overdid her applications of rouge.

Yet this woman, who even in her heyday possessed only a hothouse beauty, had something throughout her life which was infinitely more important. Her personality was unconquerable, her zest for life unextinguished. When she appeared, during the last period of her reign, in the King’s salon or at Court festivities, where many young, beautiful, and elegant women were present, and where she might well have feared competition, all eyes centred on her, although she was young and beautiful no longer.

It is true that, in spite of all her despairing efforts, the decline of her charms was obvious enough, but her general appearance and bearing seemed to command: “Look at me! Here I am!” It was her confidence in her own personality and authority which gave her such self-possession. She had never in her life been shy or diffident, and her unconquerable spirit alone had guided her through all the storms of life. At the outset youth and beauty had assisted her, and, when the time came, she was able to replace these two gifts of nature not only by art and cosmetics, but by intelligence, influence, and power. She was no ordinary woman, and no commonplace courtesan.

She fought to the end, and would never surrender an inch of what she had won. Even on her death-bed her chief thought was for her beauty. She hoped, even then, that the world might not be allowed to see her decline.

As her last hour approached and the priest, who had given her the last sacrament, was about to take leave of her and go, she called to him, smiling: “Wait a moment. Father—we will go together!” Then she quickly put a little rouge on her cheeks, to hide the deathly pallor of her face, and fell asleep. A few hours later she was dead.

The court of Louis XV. and Madame de Pompadour. Her political power and general influence.

Louis XV. also indulged in another amusement. He always affected to separate the king from Louis of Bourbon; and whilst he allowed his mistresses and ministers to give their instructions to the ambassadors he sent to foreign courts, he employed secret agents of his own to counteract their designs by pretty artifices; the pleasure of teasing those to whom he had yielded up his power being the sole object of this contemptible conduct.

The truth was that the king had grown profoundly ennuie and selfish. Life had lost its illusions for him, and he was annoyed by the sight of pleasure or happiness in others. A sardonic smile disfigured his still handsome features; to inflict pain or annoyance had become a real pleasure for him. If a courtier affected a youthful tone no longer in accordance with his years, the king, whose memory was unerring in this respect, never failed to remind him of his age: he was the first to detect in others wrinkles and all the signs of declining years.

To those who were afflicted with illness, the king spoke of their end as inevitable, or at least as approaching. Often, when he travelled with Madame de Pompadour, he caused the carriage to stop near a churchyard, in order to learn if it contained any newly-made grave. Notwithstanding the horror such subjects gave her, the king delighted to speak to his mistress of death. Like many voluptuaries, he was of a melancholy, and even morbid disposition.

The court over which Louis XV. and Madame de Pompadour presided was fully worthy of them. That confusion which is inseparable from a great convulsion reigned there, as well as in every other portion of society. The old noblesse were cast into the shade by a new and more wealthy aristocracy, sprung from the bourgeoisie, and which bought lands, vassals, and feudal titles.

When ranks are thus displaced in a nation, owing to the decay of one class and the rise of another, it is a proof that the institutions are no longer fitted to the age; and from that moment they necessarily become despised and unjust. A greater feeling of equality sprang from this state of things; though, as it did not result from the natural tone of society, but, on the contrary, from its corruption, it only proved another sign of evil.

Both the new and the old nobility joined in the common pursuit of pleasure before their final fall. Bad taste and frivolousness marked their amusements. Titled ladies, who eagerly sought the favour of being allowed a seat in the presence of Madame de Pompadour, visited in secret the popular ball of the Porcherons-, or amused themselves by breaking plates and glasses in obscure cabarets, assuming the free and reckless tone of men.

Their husbands in the mean while embroidered at home, or paced the stately galleries of Louis XIV. at Versailles—a little painted figure of cardboard in one hand, whilst with the other they drew the string which put it in motion. This preposterous amusement even spread throughout the whole nation, and grave magistrates were to be met in the streets playing, like the rest, with their pantins. This childish folly was satirized in the following epigram: “D’un peuple frivole et volage, Pantin fut la divinite. Faut-il être s’il cherissait l’image Dont il est la réalité ?”

The general degeneracy of the times was acknowledged even by those who shared in it. The old nobles ascribed it to that fatal evil — the want of female chastity. Never, indeed, had this social stain been so universal or so great. “Had our race remained pure from the intermixture of plebeian blood,” they argued, in their pride, “we could not have fallen so low.”

With all this profligacy, there was mingled a strong philosophic tone. Towards the close of Louis XV`s reign, and to the king’s infinite displeasure, the Anglomania assumed a marked popularity. The ingenious possessors of “pantins” visited England, in order, as they said, “to learn how to think.” The progress of this spirit was visible even in those whose position bound them most to resist it.

Madame Louise, the daughter of Louis XV., when she had determined on embracing a monastic life, chose the Carmelite order, because, in this order, there is no perpetual abbess, but a superior elected every three years: a custom which the daughter of an absolute king thought more in accordance with the spirit of equality.

Her brother, the dauphin, and who was considered the foe of the philosophers, whilst he approved the condemnation of Rousseau’s “Emile,” observed of the Contrat Social,” — “The case is different with this work; it only treats of the rights of kings, and these can be discussed.“ When institutions begin to know their own weakness, is not their hour nigh ? The royal and aristocratic element was declining, whilst the popular and philosophic power rose in the ascendant; and both parties felt that it was so.

Whilst monarchy was thus swiftly and surely undermined by society itself, the weak and vacillating power seemed anxious to hasten its own ruin. The mass of “the nation had become more intellectually enlightened, and more immoral than it had ever yet been; and yet the court persisted in its weak, despotic course of conduct.

Government alternately yielded to the spirit of the age, or vainly sought to control it. Scepticism was abroad, and practical intolerance was still exercised by the clergy. State prisons were filled with untried captives, the victims of favourites and royal mistresses, at the very time when democratic philosophy was most popular.

The right of a nation to govern itself was already discussed, yet Choiseul ministered to the extravagance of the king and his mistress, as though the wealth of the kingdom were their own private property.

At the same time, no one was unconscious that a great crisis was inevitable. The subject was even discussed in the drawing-room of Madame de Pompadour, and in the hearing of her confidential attendant, Madame du Hausset, who thus alludes to this remarkable fact: – “This kingdom” said Mirabeau (the father of the celebrated tribune), “is in a deplorable state. There is neither national energy nor the only substitute for it — money.” ‘It can only be regenerated,’ said La Riviere, ‘by a conquest like that of China, or by some great internal convulsion: but woe to those who live to see that! The French people do not do things by halves.’ These words made me tremble, and I hastened out of the room.”

Madame de Pompadour herself was aware that the actual system was doomed to perish, but satisfied with her favourite exclamation, — “Apres nous, le déluge” — Let the flood come when we are gone, she did nothing to effect a radical change. Her caprices increased the evils which were ruining the State: favourites and ministers succeeded one another under her sway ) they knew the unstable tenure of their power, and hastened with their creatures to drain the resources of the country before their day was past. But if Madame de Pompadour’s guilt was great, so was the retribution by which it was attended.

The most rigid moralist could not have desired a severer punishment for the king’s mistress than that brought down upon her by her own vices. The last years of this woman who governed France —who received more than queenly honours from the courtiers, and who lived surrounded by all the pleasures boundless wealth can give — were literally poisoned and abridged by a soul-devouring ennui. The death of her daughter by her husband, and whom she had destined to marry one of the first nobles in the land, filled her with grief.

The loss of her beauty, and the increasing indifference of the king, added to her melancholy. She often declared that, for a handsome woman, death itself was better than to see her charms fading away.

With all her vices, Madame de Pompadour was not insensible to the unhappy state of France. She saw and lamented that very degeneracy of the times which she had aided, and to which she owed her elevation. She had imbibed enough of the philosophic spirit to perceive that the country was on the brink of ruin; and not even her selfish exclamation, “After us, the flood,”—could always stifle the voice of her conscience.

It was no slight addition to her grief, that the general hatred of the nation ascribed to her all the misery of France. Every unpopular measure of the cabinet; every reverse in war, was laid to the detested name of Pompadour. If to these causes of melancholy be added general ill-health, and the consciousness that habit and pity were the only feelings the king now felt for her, it need scarcely be wondered that Madame de Pompadour should term the life she led “a continual death.”

At the same time, she had not enough courage or principle to leave the scene of her splendid misery. Pride kept her chained to her throne, and made her reign to the last. It is, however, probable that if Madame de Pompadour had lived longer, she might have edified the world with the sight of her conversion. The unaffected piety of the injured queen inspired her with involuntary admiration and respect for religion.

Very different, indeed, were the declining years of Maria Leszczyńska and those of the Marchioness of Pompadour. The patient and pious queen laid her sufferings at the foot of the Cross: insulted by her husband and his mistresses; neglected by the courtiers; deeply afflicted by the loss of her children, whom she had loved most tenderly, she still found in religion the courage necessary to support her grief, and effectual consolations in the practice of a boundless benevolence.

Ennui, shame, and remorse, marked the last days of Madame de Pompadour. The king, indeed, was induced by compassion to pay her the greatest attention during her last illness. She was, contrary to the usual etiquette in such cases, allowed to die in Versailles — the exclusive privilege of royalty. Her will remained, to the last, the law of France, and she issued forth orders even from her deathbed.

But scarcely had she ceased to exist when her remains were unceremoniously hurried out of the palace, and the king, looking from his window, coolly remarked that the marquise had rainy weather for this her last journey. It was to be thus honoured and thus loved that Madame de Pompadour had sacrificed all that woman should hold most dear and revered.

Though the social influence of Madame de Pompadour was far from being great or extended, it is worthy of consideration. The mistresses of Louis XV. had more direct political action than those of his predecessor, but their general power on society was infinitely less. Notwithstanding her talents and the good education she had received, Madame de Pompadour never lost the tone of a bourgeoise.

She gave evident proofs of vulgarity in the coarse nicknames which she bestowed on her female friends. She was imitated in this by the king, who called his daughters by appellations little remarkable for either delicacy or euphony.

The taste of Madame de Pompadour was essentially bad: as her admiration of Bernis’ verses would suffice to show, did not the school of art she encouraged prove it more clearly still.

The shepherdess in hoops of Watteau and Boucher, and the corrupt style which distinguished the fashions in dress and furniture of the period, owe much to her patronage. She exaggerated the defects of her contemporaries, and never endeavoured to substitute for them anything of pure artistic beauty. She had, however, the merit of having led to the establishment of the manufactory of Sèvres porcelain.

Madame de Pompadour was desirous of securing a literary influence; which, vith her power of giving places and pensions, would have been an easy matter, had she known how to act. She, indeed pensioned such second-rate authors as Marmontel, Duclos, and Bernis; but though Voltaire unblushingly protested that he was devoted to her, because it was his duty, as a good citizen, to be so—apparently considering the existence and position of a royal mistress as a sort of national institution—she did not care to influence the king in his favour.

Louis XV. always disliked that intellectual monarch, whose reign, he felt, eclipsed his own. Both he and Madame de Pompadour were so blind to their real interests as to neglect the power they might have secured, until it was beyond their grasp, and fell into the hands of Parisian ladies and farmers-general. Madame de Pompadour did, indeed, attempt to tame, as she said, Rousseau, and accordingly sent a hundred louis to the proud and irritable author.

He declined her present in a letter of such haughtiness that she was wounded to the quick, and protested she would have nothing more to do with that owl. The truth was, that the literary and philosophic party expected more than pensions from Madame de Pompadour; the time was gone when they could be so easily satisfied: they aimed at receiving from her no less than the same degree of flattery and consideration awarded to them in every Parisian circle.

But, though she could venture to direct the destinies of France, Madame de Pompadour shrank from the responsibility of encouraging, too openly, the formidable philosophic power: at the same time, she committed the great error of bestowing on that power, the sort of encouragement which entitles the receiver to expect more.

Through her favourite medical attendant, Quesnay, she often communicated with Diderot, D’Alembert, Duclos, Helvétius, Turgot, and Buffon — freely mingling with them when they visited Quesnay’s entresol in Versailles, but never asking them up into her own drawing-room.

The men whom Frederick and Catharine had accustomed to the praise of crowned heads, were not likely to be highly flattered by the indirect notice of Madame de Pompadour. Another error which she committed, was to endeavour to place Crébillon, the tragic poet, above Voltaire (Prosper Jolyot Crébillon 1674-1762, was a French author. He was considered around 1710 in France as the greatest dramatist of his generation.).

Crébillon was poor; she wanted a poet to patronize and exalt; she chose him. Voltaire, deeply irritated, never forgave her this offence. Madame du Maine, who, in matters of taste, was still influential, zealously defended her former protege; and Madame de Pompadour had the mortification of perceiving that, though no one denied Crebillon’s tragic power, Voltaire, in spite of all she might do, was still the great idol of the age.

Madame de Pompadour was more successful when, entering into the views of the philosophers, she aided them in the expulsion of the Jesuits. Notwithstanding the disinclination of the king, and the opposition of the whole royal family, she succeeded, with the aid of her creature, Choiseul, in banishing the Jesuits from France, ten years before their order was expelled from the other European states.

It has been said that she was actuated in this by a motive of personal animosity; and, though the assertion is not, perhaps, sufficiently proved, there is nothing in the life and character of Madame de Pompadour, to justify the belief that she acted from a feeling of principle.

The expulsion of the Jesuits was a very serious blow given to religion in France. Choiseul, the philosophers, and the Parliament, united their efforts to those of Madame de Pompadour, in order to carry a measure they all desired, though through widely different motives. The Parliament unwisely yielded to their old prejudices, as Jansenists, and eagerly aided the philosophers; for whom, on other occasions, their only feeling was one of bitter hostility.

Whatever opinion may be held of the Jesuits — and it is not our intention to discuss here the merits of this celebrated order — their expulsion was certainly not justified then. They had possessed no real power in France since Louis XIV. and Madame de Maintenon; they were, indeed, protected by the Queen, Marie Lecsinska; but she was utterly without influence.

It was precisely because they were so weak, that they were attacked. Institutions perish when the strength against which violence would have been of no avail has long been spent. It is not when they stand in the evil pride of their power; but it is when they grow feeble and decayed, that the memory of past hatred rises up against them, and their fall seems then less an act of justice than one of vengeance.

Madame de Pompadour was less successful when she attempted to exercise her power in favour of the parliaments, who were then openly protected by Choiseul. “Do not mention them!” once hastily observed Louis XV., starting up from the apathy with which he usually acceded to the plans of his mistress, “I tell you they are an assembly of republicans.”

Madame de Pompadour interfered with more success when she encouraged the doctrines of political economy: one of the results of the new philosophy. She did not, indeed, modify these doctrines by any original views of her own, but she did much by favoring their free development.

Madame de Pompadour and the death of Louis XV.

Clever, though too light and volatile—haughty, and yet supple — the Duke of Choiseul had early learned the art of ingratiating himself in famale favour; thus carrying into practice the advice of Madame de Montmorin to her son: ” If you wish to succeed in France, fall in love with all the women.” His light, caustic wit, and skilful flattery, compensated for the insignificance of his personal appearance. The universal, and not very disinterested desire, which then existed, of making gallantry a means of success in ambition, had reacted on the character of the men by whom it was employed.

Women are excellent judges of a certain species of individual merit. An elegant address, natural manners, taste, wit, and eloquence, generally find favour with them. The superficial nature of their education renders them less capable of appreciating gravity of thought and solidity of judgment. The men whose task and interest it was to please women, naturally adopted the manners most likely to accomplish this purpose.

But, though female influence thus gave an undue importance to mere externals, the frivolous tone of society, and the tendency which therefore existed to govern it by the laws of ridicule, were not exclusively the work of women: these characteristics of the last century may more fairly be attributed to the want of political rights, which induced men to win by favour and intrigue what they might have sought openly in a free country.

Whilst Madame de Pompadour governed the State, Louis XV. continued his life of indolence and shameless profligacy. He was by far too clear-sighted not to perceive that monarchy was declining, and that a great change must necessarily take place in the condition of the nation; but not even this knowledge could rouse him from his selfish apathy. He felt tolerably certain that no serious disturbance would occur during his lifetime: “the rest concerns my successor he often observed. It did, indeed, concern the hapless Louis XVI. The prestige which had so long environed Louis XV. vanished; for his people saw what sort of a king was on the throne.

Louis XV. the beloved, was now named thus only in the almanacks, published every year: the endearing epithet had long been erased from every heart in France. When he appeared, in public, he was received with ominous silence,— contempt and hatred were the secret feelings of those who gazed on him. A life of voluptuous indulgence soon bred satiety: ennui, as well as a feeling of inquisitiveness natural to unoccupied minds, made Louis XV. seek for amusement in an acquaintance with all the scandalous news of the day.

To know the minutest details of the private life of his courtiers and ministers, as well as to be informed of all the intrigues that took place in Paris, was one of the greatest pleasures and most earnest occupations of the king. For this purpose he kept a private police of his own; being too suspicious to trust entirely to the lieutenant of police.

This functionary was, however, summoned every Sunday to the presence of the king, with whom he spent several hours. He then laid before his majesty every fact of importance or interest which numerous spies, of every rank, had discovered in the course of the week. It was also his task to read to him the extracts from letters which had been unsealed and read by the post-office authorities,— an infamous custom, first introduced under Louis XIV. by the minister Louvois.

Louis XV. sometimes communicated to his ministers these extracts from the private correspondence of his subjects. The Duke of Choiseul was often favoured thus; but, being naturally indiscreet, he divulged amongst his acquaintances matters affecting the honour of individuals, or exposing them to scorn and ridicule. The king, besides the information he thus gained, also heard every morning five classes of police reports, concerning the princes of the blood, the courtiers, bishops, ministers, clergymen, women of dissolute life, &c.

The deep, heart-rending misery of the working classes had at length forced itself on public attention. Persons of every rank began to consider the best means of alleviating a wretchedness to which even the king and Madame de Pompadour could not remain wholly insensible.

Quesnay, their favourite surgeon, was one of the most popular economists: his views were inserted in the ” Encyclopédie,“ with the chief writers of which he was on intimate terms. He had also many influential friends among men of rank: one of his adherents was Mirabeau the elder, that “friend of man” who wrote twenty volumes of philanthropic works, and behaved like a fierce tyrant to all those over whom he had power.

Louis XV. took some interest in his physician’s system, and indulged in the novel amusement of causing his essays to be printed, revising the proofs with his own royal hand. Gournay (Jean Claude Marie Vincent, Marquis de Gournay 1712-1759, was a French economist.

Gournay came from a family of Breton ship chandlers and was the son of a rich merchant) opposed the views of Quesnay ( François Quesnay 1694-1774 was a French physician and economist. He is considered the founder of the school of economics physiocratic and encyclopedist.) by a system based on wholly different principles. This difference of opinion led to a bitter controversy between their respective partisans.

The women took an active share in the matter: most of them imperiously proscribed in their circle any views but those they had chosen to adopt; those who would willingly have remained indifferent on such subjects were not allowed to do so; so deeply and universally felt was the necessity of some radical change.

None showed more zeal in the cause of political economy than the pretty and agreeable Madame du Marchais, a relative of Madame de Pompadour’s, and the wife of the dauphin’s valet de chambre.

Though this lady held a somewhat subordinate position, her connection with Madame de Pompadour, and the great charm of her conversation, drew around her the most eminent men of the day, and rendered her little apartment in the palace of Versailles the rendezvous of the most intellectual society of those times. There was much in Madame du Marchais, afterwards Madame d’Angivilliers, to fascinate and attract. She was diminutive in person, but pretty and graceful as a fairy. Her mind was remarkable for two high and rare qualities; an extreme clearness of understanding and a complete impartiality, even with regard to those subjects which interested her most.

Madame du Marchais was thus admirably adapted to the part she had taken on herself as expounder of the rival systems of the day. The elegant perspicuity of her language, the precision with which she conveyed, in a few words, the substance of whatever treatise or discourse she wished to condense for the benefit of her hearers, were invaluable to her friends, at an epoch when the fate of the most important questions often hung on the manner in which they were discussed.

The comprehensiveness of her intellect enabled Madame du Marchais to abstract herself whenever she pleased from ordinary cares, without neglecting them in the main. Her mind was stored with all that had been written for or against the science she favoured; she was an authority to be consulted with perfect safety, for no party spirit ever disfigured the clearness and calmness of her statements.

The letters of Turgot to Terrai, Necker’s treatises, the dialogues of Galiani, and Morellet’s refutations were alike read and consulted by the dispassionate Madame du Marchais.

Though she saw persons of every class, Madame du Marchais chiefly received academicians and political economists. La Harpe, Diderot, Marmontel, D’Alembert, Duclos, Thomas, and Quesnay constantly met at her house. Such was her influence that she not only named academicians whenever vacant seats occurred in the academy, but she had even the occult power of directing the motions of that body; whom she once caused to propose an eulogy of Sully for the “concours” of eloquence.

The essay of Thomas had the prize; but the triumph he obtained was less his own than that of Madame du Marchais’s friend, Quesnay, whose principles he had developed under the name of Sully. Never, indeed, was literature less free and independent than in those times, when even the fairy tales of Duclos took a philosophic turn.

Death of Dauphin

The inclinations and great talents of Madame du Marchais entitled her to do for political economy in France what Madame du Chatelet had effected for Leibnitz and Newton before her such, indeed, was her aim, and she devoted her whole energies and attention to the purpose of aiding the progress of doctrines she believed calculated to rescue her country from its unhappy condition.

Time showed that deeper changes than those it was in the power of political economy to effect for France were needful; but the aim of Madame du Marchais was not the less noble or pure. Madame du Deffand, incapable of appreciating anything elevated or unselfish, sought to chase her ever-renewing ennui by attacking all the economists with the utmost coarseness and vehemence.

She partook, however, of Madame du Marehais’s excellent suppers, in company with the hated tribe, but did not fail to turn her friend into ridicule on every favourable occasion. Undeterred by her satirical remarks, Madame du Marchais steadily persevered in her object. Many women of those times shone more than she did by the exercise of frivolous talents, but none had an aim so disinterested and so useful.

Disgrace of Choiseul.

The favour, and consequently the power of the Duke of Choiseul (Étienne-François de Choiseul d’Amboise 1719-1785) continued even after the death of Madame de Pompadour. His light frivolous manner of treating the most important state matters amused without ever wearying the king.

As long as Choiseul remained minister, the philosophic party—especially that worldly epicurian portion which met at the house of Madame du Deffand (Marie de Vichy-Chamrond (ou Champrond), marquise du Deffand 1697-1780, was a famous French salonière in the Age of Enlightenment. Her culturally and historically interesting letters were received not only in the history of literature, but they have also found to be one of the most astute minds of her century.) — raised their patron to the skies, and enjoyed a considerable degree of his countenance. Thus encouraged, they expressed their opinions with still greater freedom than they had been in the habit of manifesting.

The death of Louis XV.’s only son was also a great subject of triumph to the philosophers. They supposed the dauphin, as a moral and religious prince, to be their natural foe: he was, indeed, the foe of their errors; but he had a virtue of which they knew nothing, and that was a singular tolerance for opinions the most opposed to his own.

But he was the partisan of the Jesuits, and very much opposed to the power of Choiseul: these were the real causes of the dislike of the philosophers. He died at Compiègne, where the court was delayed until his decease, which was hourly expected, should have taken place. The prince, who remained sensible to the last, could see from the window of his room the preparations which all the courtiers were making for their approaching departure. “They are getting impatient; it is time for me to be gone,” he observed to his doctor, with a bitter smile. The agony of this last hour was, however, soothed by the devotedness of the dauphiness: a pure, noble-minded woman, who waited on her husband, through his long and painful illness, with unwearied love, and who died of grief for his loss.

The death of his son was announced to the king by his eldest grandson, the Duke of Berri (Louis XVI.), being introduced into his presence as Monseigneur le Dauphin. This event appeared to rouse the sovereign from his usual apathy. “Poor France!” said he, with a deep sigh, “thou hast now got a king of fifty, and a dauphin of eleven!”

And as he cast a sad and troubled look on the child before him, the future woes of his posterity seemed for a while to be revealed to, and to appal, the guilty soul of Louis XV. Choiseul thought himself fairly consolidated in his power by the death of the dauphin. The king was getting old, and it seemed scarcely probable that he would take another acknowledged mistress.

Such was not the wish of the handsome and unprincipled court ladies; who, on the death of Madame de Pompadour, strove to succeed her in the favour of the monarch. Their blandishments were, however, lavished in vain: a common courtesan was destined to succeed the bourgeoise, and to rule over the court of France.

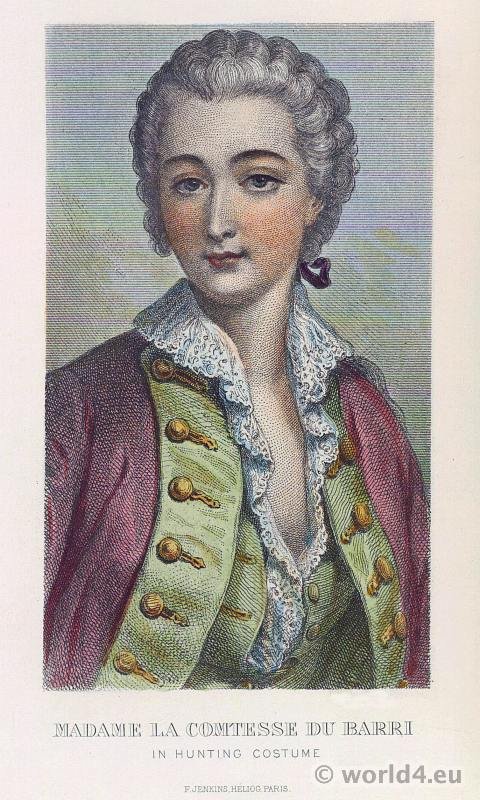

The beauty of Madame du Barry

All the sermons that could be preached on the increasing immorality and shamelessness of the times, would never speak so eloquently as the love of Louis XV. for Madame du Barry.

The first mistresses of the king had been comparatively modest women: they were highly born, clever, and educated ladies, who knew how to sin with a proper regard for the bienseances: some of them even possessed high qualities, and strove to make a worthy use of a corrupt power.

Madame de Pompadour, a bourgeoise and a parvenue, though she served the passions of the king in an infamous manner, and was deservedly hated for her insolence and tyranny, was still an immaculate woman, if compared to her successor.

To the pure and modest beauty of a Madonna, Madame du Barry united the language and manners of a common courtesan. It was this contrast and this licentiousness that fascinated the corrupt heart of Louis XV.

Even in the choice of royal mistresses may be traced the descending tendency so characteristic of the times. From the daughters of nobles to the wife of a bourgeoise, and from her again to a woman of the people, the differences were sufficiently striking.

When Madame du Barry was declared the mistress “en titre” of Louis XV., all the high-born ladies—who construed it into an open insult that none of them should have been thought worthy of the place bestowed on her—opposed her favour with violent and bitter hostility. At the head of this party were the Duchess de Grammont (Béatrix de Choiseul-Stainville, duchesse de Gramont 1730-1794) and the Princess of Beauveau (Marie Charlotte de La Tour d’Auvergne 1729-1763).

Both were former favourites of Madame de Pompadour. Madame de Grammont, a reckless, despotic woman, the sister of Choiseul—over whose mind she possessed great influence—had vainly attempted to succeed Madame de Pompadour in the favour of the king. Exasperated and blinded by her wounded pride, she prevented her brother from accepting the protection Madame du Barry was at first willing to offer.

Not satisfied with being, through Choiseul, the arbiter of every important state affair, and the distributor of places and favours, Madame de Grammont urged her brother to use his ascendancy over the mind of the king, in order to banish Madame du Barry. As it long remained doubtful which, of the minister or the mistress, would retire vanquished from the contest, Madame de Grammont and the Princess of Beauveau enlisted almost the whole court in their cause.

Whilst the saloons of the Duke of Choiseul and his sister were daily thronged with courtiers, Madame du Barry saw herself almost wholly deserted. The vindictive Madame de Grammont even caused libels to be circulated and songs to be sung against her rival, wherever the royal favourite might go: even at Marly, and in the presence of the king, she was followed with insults.

The nobles, through a spirit of caste; the philosophers, because they were protected and encouraged by Choiseul and his sister; the people, from hatred to the royal profligacy,— all took up the cry against Madame du Barry whose only crime was, that she was fit for the degrading position to which the love of the king had called her.

She patiently endured these insults; and Louis XV., with still greater patience, put no stop to the insolence of M. de Choiseul. The minister became convinced that the king could not dispense with his services. In order to render himself still more necessary to him, he married the young dauphin (Louis XVI.) to Marie Antoinette, the favourite daughter of Maria Theresa: he also hoped, by this alliance, to give himself a hold on the future sovereigns of France.

The chief consideration which kept Louis XV. faithful to his minister so long, was, in fact, his own extreme indolence. Madame du Barry, seeing at last that the warfare waged against her was a deadly one, took up the struggle in good earnest, by attacking the philosophers and the parliaments, and protecting the religious party. Selfpreservation rendered her active: she teazed the king incessantly to send away Choiseul. Louis XV. still hesitated between his love for his mistress and his value for his minister: the imprudence of Madame de Graminont precipitated the catastrophe.

With the secret connivance of her brother, the duchess travelled through France, entering into communications with the chief agitators of the provincial parliaments. Her design, and that of Choiseul, was to establish a powerful link between all the parliaments and that of Paris, and thus, in case of necessity, to renew the times of the league and the Fronde. This was enough to doom both Madame de Grammont and her brother in the mind of the king.

When he saw that, not satisfied with interfering with his pleasure, Choiseul and his audacious sister sought even to rouse the nation against him, Louis XV., yielding to the representations of Madame du Barry, suddenly dismissed the daring minister. M. de Choiseul was sent into exile; in consideration of his amiable wife, the king allowed him to retire to Chanteloup, where he possessed a magnificent residence. Madame de Grammont, banished from the court, became a provincial canoness, and lived in a state of mediocrity, until she ascended the scaffold, in the time of the Revolution.

The disgrace of Choiseul was a real triumph, and showed not only the weakness of royal authority, but the immense progress the philosophic party had made. All that the land held of noble and distinguished flocked around the minister in his exile; and, as though to brave the monarch more openly still, there was erected at Chanteloup a column, on which all the names of the visitors were inscribed, in order to perpetuate the memory of this protest against the personal will of the sovereign. Never was the powerlessness of absolute monarchy more clearly manifested.

Madame du Barry made a moderate use of her triumph. Though so much hated and reviled, she was indifferent to revenge. If she had caused Choiseul to be dismissed, it was because his ruin or hers was necessary.

This natural kindness of heart, and the perfect good humour which she always displayed, greatly contributed to fascinate the king. “We must shut up the bastille; you will send no one to it,” he often observed to her. One of Madame du Barry’s first acts was to make her lover, the Duke of Aiguillon (Emmanuel Armand de Vignerot du Plessis de Richelieu 1720-1782), minister.

It is asserted—on somewhat doubtful authority, indeed, but the temper of Louis XV. renders the fact probable that Madame du Barry ordered D’Aiguillon to go and thank the king for the foreign ministry, though it had never been given to him; and that, with his usual apathy, Louis XV. submitted to the will of his mistress, and allowed D’Aiguillon to enter on the duties of the office she had thus bestowed on him of her own authority.

The political power of Madame du Barry led to what had been the constant aim of monarchy since Louis XIV., the suppression of the parliaments. This coup d’etat, the work of a capricious favourite and of her lover,—for it was D’Aiguillon, who, whilst governor of Brittany, had rendered himself so notorious in the affairs of La Chalotais,— did not produce a very deep or real effect on the philosophic power of society.

The parliaments represented Jansenism: there was no real sympathy between them and the philosophers ; who looked upon them as an old and worn-out form of opposition, and whose aim was far more bold and destructive. The influence of Madame Du Barry was extremely slight. On society at large she had no power: nor, indeed lid she seek to exercise any. Her own conversation was free from wit or delicacy: it was bold, and even licentious.

At court, Madame du Barry exercised, however, some power. The opposition, which had been raised as long as Choiseul was in authority, ceased when the power of the royal favourite was fully consolidated. The most noble names in the land were, ultimately, inscribed at the door of Madame du Barry, as they had formerly been inscribed on the column of Chanteloup.

It was on these persons that the freedom of speech of Madame du Barry — a freedom in which the king evidently took pleasure—reacted. In order to win a few favours, and pay their court to the monarch, Richelieu and other old courtiers entered, as they said themselves, on the ways of perdition, and relinquished that elegant phraseology, for which they had been remarkable so long, in order to adopt the language which Madame du Barry had picked up among abandoned women and chevaliers d’industrie, the companions of her youth.

DEATH OF LOUIS XV.

Though the necessity of her position had made Madame du Barry enter into the views of the devout party since she opposed the philosophic supporters of Choiseul, whom they naturally disliked — there existed no real sympathy between her and the religious portion of the nation.

Never, perhaps, was there so uncompromising a reproof administered, as that which Louis XV. received, in the presence of his favourite and of the whole court, from the Bishop of Senez; who, when preaching before him, reproached him with the numerous errors of his life, and with that last scandal of all, the favour of Madame du Barry, in terms which might well have made the monarch blush with shame, if shame had not long since ceased to colour that withered cheek.*

Notwithstanding the audacity of his reproofs, or perhaps on that very account, the same Bishop of Senez was called upon to preach before the king during the Lent of the year 1774. He chose for one of his texts the words of the Prophet: “Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!“ and when the forty days were past, Louis XV. was lying dead in the royal abbey of Saint-Denis.

* “Qu’il avait été ramasser dans le ruisseau les vestes de la corruption publique,” was the expression used by the Bishop of Senez.

A sudden attack of the smallpox carried off the guilty king in the sixty-fourth year of his age. As long as there seemed any chance of his recovery, the death-bed of the sick monarch witnessed a struggle as disgraceful as that of Metz. The set of devotees, who had submitted to the degrading protection of Madame du Barry, delayed, as long as decency would allow, the religious rites which must necessarily have caused her removal from court; whilst, on the contrary, the atheistical and philosophic friends of the ex-minister Choiseul, sought by their intrigues to terrify the dying king, and hasten the ceremony that was to ruin Madame du Barry. Religious terror at length prevailed once more over the mind of Louis XV.

He ordered D’Aiguillon to take away Madame du Barry; and, after a tender and final adieu to his mistress, he delivered himself over to his confessor. As it was not yet quite certain whether the king would recover or not, several persons of the court thought fit to call on Madame du Barry in her retirement; and, in consequence of this were, for several years afterwards, looked upon with disfavour under the reign of Louis XVI.

When doubt no longer existed with regard to the approaching death of the king, the event was expected with general apathy. Prayers were offered up for him by the clergy in the churches; but few of his subjects joined in these petitions.

The poissardes kept their vow: Louis XV. had neither a “pater” nor an “ave” from them. With the exception of the partisans of Madame du Barry, none of the courtiers cared to conceal their entire indiiference on the subject of the life or death of their sovereign. The neglected daughters of Louis XV. alone had sufficient courage and devotedness to attend on their father; whose loathsome disease, aggravated by a dissolute life, filled all who approached him with horror.

On the 10th of May, 1774, the whole court was hourly expecting, in the “oeil de boeuf” of the palace of Versailles, the dissolution of the king. The dauphin, and the rest of the royal family, were to leave the palace as soon as Louis XV. should have breathed his last. Everything was in readiness, and one of the few attendants who lingered in the chamber of the dying monarch had placed a lighted taper behind one of the windows, to act as a signal. It was known beforehand, that when that feeble light vanished, Louis XV. would have ceased to exist.

The taper was extinguished. The dauphin was then with his young wife in a remote part of the palace. A sound, like that of loud thunder, was heard: it was the rush of innumerable courtiers, eagerly pressing forward to do homage to the new king. Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette trembled and turned pale.

An instinctive and irresistible impulse made them both fall down on their knees: a feeling of dread seemed to usher in for them their most inauspicious reign. With heads humbly bowed, clasped hands, and gushing tears, they exclaimed, in a faltering tone, “Guide us, oh Grod! Protect us! we are called to reign too young.”

How often, yet, whilst reading the history of that fatal reign, will human wisdom ask, Oh, why did not Heaven hear that prayer?

The Countess of Noailles entered the apartment, and was the first to salute the new sovereigns. All the grand officers of the crown followed in succession. When this duty was over, Marie Antoinette, leaning on her husband’s arm, entered the carriage in waiting, and rode off with the rest of the royal suite.

As soon as it was known that the young king and queen were gone, the courtiers deserted the royal palace. Every one now dreaded to stay any longer near the deceased monarch, whose decaying remains exhaled a contagion as foul as the foul corruption of his reign.

A few attendants watched by the corpse, which was placed in a coffin without being embalmed, and conveyed as speedily and privately as possible to Saint-Denis. There it rested; until the people, maddened with hatred, caused by ages of misery, rose in their wrath, and, after immolating the living, spent the last efforts of their vengeance on the senseless dead.

Continuing