Dictionary of Dress BY JAMES ROBINSON PLANCHÉ. CYCLOPAEDIA OF COSTUME.

BACK AND BREAST.

The usual form of expression employed in official documents, orders, inventories, &c., of the seventeenth century, to designate the body armour of that period, which consisted chiefly of a back and breast plate, and some sort of defense for the head. In the ‘Militarie Instructions for the Cavalrie,’ dated 1632, the harquebusier, “by the late orders rendered by the Council of War,” is directed to wear, besides a good buff coat, “a back and breast like the cuirassier, more than pistol-proof,” &c. (See under BREAST-PLATE and CUIRASS.) “The arms, offensive and defensive,” says the Statute of the 13th and 14th of Charles II., “are to be as follows: the defensive arms (of the cavalry), a back, breast, and pot, and the breast and pot to be pistol-proof. “Pikemen are to be armed, in addition to the pike, “with a back, breast, head-piece, and sword.”

BADGE.

The earliest personal distinction of the Middle Ages, and the origin of armorial insignia. Wace tells us that at the Battle of Hastings all the Normans had made or adopted cognizances, that one Norman might know another by, and that none others bore; but we fail to distinguish any such signs in the Bayeux Tapestry. Upon the general adoption of regular and hereditary armorial bearings, the badge was transferred from the chief to his retainer, and from the banner to the standard. It was likewise used for the decoration of tents, caparisons of horses, and household furniture. Modern writers have frequently confounded it with the crest and the device, but it was perfectly distinct from both. It was never borne on a wreath, like the former, and it differed from the latter by becoming hereditary with the arms, while the device, properly so called, was only assumed on some particular occasion, to which it usually bore a special reference. (See CREST and DEVICE.)

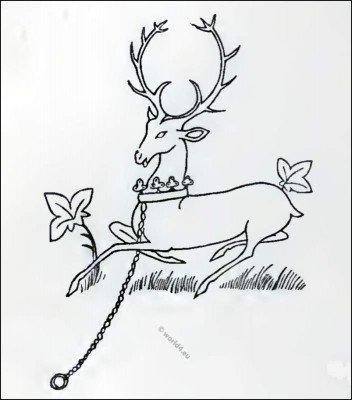

The etymology of the word “badge” is uncertain. Johnson derives it from the Italian bajulo, to carry. Mr. Albert Way more probably suggests from the Anglo-Saxon beag, a bracelet. (Note to ‘Prompt. Parvulorum,’ tom. i. p. 21.) The Norman term cognoissance, anglicised cognizance, is more explicit, and was the one in use during the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. In the fifteenth the word “badge” appears incorporated with the English language, and one of the earliest lists of badges is of the reign of Edward IV. The badge was at that period embroidered on the breast, back, or sleeve of the soldier or servant, and in the sixteenth century engraved or embossed on a metal plate affixed to the sleeve, such as we still see on the jackets of watermen, postillions, &c., although they now improperly display the crest or entire coat of arms of the person or company employing them. When worn by the sovereign, noble, or knight himself, it was not on the sleeve or any particular part of his attire, but introduced as a portion of the ornamental pattern with which his robe, tunic, or other vestment was embroidered. The effigies of Richard II. and his queen, Anne of Bohemia, in Westminster

Abbey, affort us a fine example of this fashion. The king’s tunic is covered with his badges of the white hart, crowned and chained, the sun issuing from a cloud, and the open broom-pod; the queen displays her family badge of the ostrich with a nail in his beak, amidst a profusion of knots, crowned initials, &c.

The Duke of Bedford, temp. Henry VI., is represented in a robe embroidered with his badge, a tree root (called by the French le racine du Bedfort), in the Bedford Missal, a MS. of the fifteenth century, and the examples might be multiplied ad infinitum.

In the Orders of the Duke of Norfolk, 36th of Henry VII!., we find “no gentleman or yeoman to were [wear] any manner of badge.” (MS. ColI. Arm., marked W. S.)

The portraits of Richard II., at Wilton House and in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster, furnish us with other interesting proofs of this gorgeous style of decoration, and in the Metrical History of his deposition (Harleian MS. No. 1319) the caparisons of his horse are powdered with golden ostrich feathers. The shields worn at the girdles by inferior officers of arms, and the small metal escutcheons occasionally found, and which appear to have been ornaments of horse furniture, are not badges, as they have been incorrectly termed by some antiquaries, except in the modern and general sense of the word, a mark or sign, as it is now applied to the plate carried by the cabmen, or when employed metaphorically, as in the well-known line of Shylock: “Sufferance is the badge of all our tribe.”

BAINBERGS. (German, Bein-bergen)

Shin-guards of leather or iron, strapped over the chausses of mail, as an additional defence to the front ofthe leg; the precursors of the steel greaves or jambs of the fourteenth century. It is probable that the term was used by the Teutonic races to designate any sort of protection for the legs. “Bainborgas bonas vi. sol tribuat.” (Lex Ripuar. cap. 36, s. II.) “Bembergas 2.” (Testamentum Everardi Ducis Forojiil.)

BAIZE, BAYS.

A well-known woollen manufacture, first made in England at Sandwich, Colchester, and Norwich, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. It was still considered a novelty in the following reign; for in Hilary Term, 2nd of James I., there was a question, whether certain Woollen cloths were subject to the duty of alnage, referred to the judges, who made a certificate, which is set out verbatim by Lord Coke in his 4th Institute, p. 31. They say, “We are resolved that all new-made drapery, made wholly of wool, as frizadors, bays, northern dozens, northern cottons, cloth wash, and other like drapery, of what new name soever, for the use of man’s body, are to yield subsidy and alnage.” (Certificate, dated 24th June, 1605.)

“Hops, reformation, bays, and beer, Came into England all in a year.” Old English Rhymes.

Those of the Walloon “strangers” who came over to England, and were workers in serges, baize, and flannel, fixed themselves at Sandwich at the mouth of a haven, where they could have an easy communication with the metropolis and other parts of the kingdom. The queen, in her third year, 1561, caused letters to be passed under her great seal, directed to the mayor, &c., of Sandwich, to give liberty to certain of them to inhabit that town, for the purpose of exercising their manufactures, which had not been used before in England. (Hasted’s Kent, iv. p. 252.)

“The strangers” of Sandwich were the most ancient, for from them proceeded those of Norwich and Colchester; and the English which dwelt at Coxhall, Braintree, Hastings, and other places, that make baizes now in great abundance, did learn the same of the strangers. (Cotton MS. Titus, B v.)

BALANDRANA. (French, balandrus, balandran.)

A mantle or cloak, similar, if not identical, with the supertotus, or surtout, worn by travellers in the thirteenth century. (See SUPERTOTUS.) In the statutes of the Order of St. Benedict, A.D. 1226, it is thus mentioned: “Illas quidem vestes quæ vulgo Balandrava et Supertoti vocantur, et sellas rubeas et fræna,… penitus amputamus.” It was prohibited to the clergy with other laical garments. “Prohibemus quoque districtim ut nulli regulares cum Balandranis seu Garmasiis vel aliis vestibus laicorum equitent vel incedant.”

(Concil. Albiense, anno 1254.)

BALAS. (Baleis, Latin ; balais, French.)

A species of ruby of a rosy colour. When engraved or incised, called “balais of entail,” “balay d’entail.” “Cum rubetis et balesiis.” (Rymer’s Feed. i. 370.) In what was called “the Harry crown,” broken up and distributed amongst several people by Henry V., was “a great fleur de lys, garnished with one great balays, and one other baleys, one ruby three great saphires, and two great pearls,” and a pinnacle of the aforesaid crown, “was garnished with two saphires, one square balays, and six pearls.”

BALDEKIN. Cloth of Baldekins. (French, baudekin.)

A costly stuff of silk and gold, so called from being originally manufactured at Baldech, or Baldach, one of the names of Babylon or Bagdad. (Ducange, in voce.) Baldekinus. “Pallas preciosus quos Baldekinus vocant.” (Mathew of Paris, 1254)

Wachter derives the word “a cambrico, pali, sericum, et German, Dach, tectum;” and the authors of the ‘Glossarii Bremensis’ from “boll, caput, and dech, tegumentum.” It was used for robes of state curtains, canopies, &c. Mathew Paris speaks of it under the date of 1247, as forming a portion of the royal vestments of Henry III., when he conferred the honour of knighthood on William de Valence: “Dominus Rex vesta deaurata facta de preciocissimo Baldekino …. sedens.” (* Mathew Paris, 1247.)

There is a town called Boldeck in Lower Germany, but it hasn`t any connection with this subject. It is constantly mentioned in mediaeval romances:

“She took a rich baudekine That her lord brought from Constantino And lapped the little maiden therein.” Lay le Freine.

“All the city was by-hong Of rich baudekyns.“ Romance of King Alexander.

“With samites and baudekyns Were curtained the gardens.” Ibid.

In the inventory of the wardrobe of Henry V. occur “a piece of baudekyn of purple silk, valued at 33 shillings,” “a piece of white baudekyn of gold at 20 shillings the yard.” In another, of Edward IV., we read of “baudekyns of silk,” and in that of Henry VIII. (Harleian MS. 2284) are entries of “green baudekins of Venice gold,” and “blue, white, green, and crimson baudekyns with flowers of gold.”

The term “baldaquin” is still in use to signify the state canopy borne over the head of the Pope, and other similar canopies suspended in churches, from the rich material of which they were generally composed.

* Matthew Paris was a Benedictine monk, English chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire.

BAZANE.

“Sheep’s leather dressed like Spanish leather.” (Cotgrave) „Red bazan“ is mentioned in wardrobe accounts of Henry VIII. (‘Archaeologia,’ vol. xxxi.)

BEAD.

Beads of various materials have been used for personal decoration, by nearly all nations, from their earliest savage state to the period of their highest civilisation. Beads of glass, jet, and amber, appear to have been much worn by the Belgic and Southern Britons, as necklaces and ornaments for the hair. Amber beads are constantly found in the graves of the Anglo-Saxons, and coloured beads are presumed to have been attached as ornaments to their swords.

Mr. Neville, in his ‘Saxon Obsequies,‘ Plate xxi., has figured two beads discovered with swords at Wilbraham, and says, “An immense blue and white perforated bead accompanied three out of the four swords, probably as an appendage to the hilt, or some point of the scabbard.” The Anglo-Normans do not appear to have affected them, at least we do not discover it, either in their paintings or writings, and it is not until the sixteenth century that the fashion seems to have raged again. Since that period, beads have ever been more or less used for necklaces, bracelets, trimming of dresses, and decoration of the hair; and the varieties of material in which they are made at the present day require no description.

BEAD-CUFFS.

Small ruffles.

BEARERS.

Randle Holmes, in his ‘Academy of Armoury,’ 1688, classes “bearers” amongst other “things made purposely to put under the skirts of gowns at their setting on at the bodies which raise up the skirt at that place to what breadth the wearer pleaseth, and as the fashion is.”

The “bustle,” therefore, so constantly the object of satire some few years ago, may claim descent from the bearer of the seventeenth century.

BODICE.

“A pair of bodies” is mentioned in the fifteenth century, and the modern word “bodice” is evidently derived from it. It occurs in the latter form in a list of the articles of a lady’s wardrobe in a play called ‘Lingua; or, the Combat of the Tongue and the Five Senses for Superiority,’ published in 1607. A “buttoned bodice skirted doubletwise” is mentioned in Goddard’s ‘Mastiff Whelp,’ a collection of satires of the time of Elizabeth, as forming part of a lady’s riding habit. The coxcombs of the seventeenth century wore bodices, as the dandies now wear stays: “He’ll have an attractive lace, And whalebone bodies, for the better grace.” Notes from Black Fryers, 1617.

BLIAUS.

(French, bliaud.) A loose upper garment, or surcoat, worn by both sexes of all classes in the twelfth century, and familiarized to us by the modern blouse, which has so nearly preserved the name.

It was worn by knights over their armour, and is frequently mentioned as lined with fur for the winter. In a close roll of the reign of King John, there is an order for a bliaus lined with fur for the use of the queen.

For the lower orders the bliaus was made of canvas and fustian. (Vide Ducange in voce for quotations.) M. Viollet-le-Duc has a long article, profusely illustrated, respecting the bliaus, which he represents as resembling in form almost every sort of surcoat, robe, or gown, of which we possess an example in sculpture or painting.

BLUE-COAT.

A blue-coat was the usual habit of a serving-man in the sixteenth, and early part of the seventeenth, century. The dramatists of those periods constantly allude to it.

“Where’s your blue-coat, your sword and buckler, sir?

Get you such like habit for a serving-man?” Two Angry Wives of Abingdon, 1599.

“A country blue-coat serving-man.” – Rowland’s Knave of Clubs, 1611.

“Blue-coats and badges to follow at her heels.” – Patient Guzzle.

It is unnecessary to multiply quotations.

The blue-coat appears also to have been the dress of a beadle as early as the days of Shakespeare. Doll Tearsheet calls the beadle a “blue-bottle rogue” in the ‘Second Part of King Henry IV.’; also in Nabbes’s ‘Microcosmos,’ 1637: “The whips of furies are not half so terrible as a blue-coat;” and the custom has continued to this day. The blue-coat laced with gold, and sometimes with a red cape, are additions of the last century. The form of the blue-coat worn in the time of Edward VI. has been preserved in the dress of the scholars of Christchurch School, London, founded by him. “Blue-coat school” and “blue-coat boys” are appellations familiar to all Englishmen. Howe, the continuator of Stowe’s ‘Annals’ tells us that many years before the reign of Queen Mary (and therefore as early as that of Henry VIII., at least), all the apprentices in London wore blue cloaks in the summer and blue gowns in the winter.

BLUNDERBUSS.

A short fire-arm with a wide bore, and sometimes bell-mouthed, carried by mail-guards as late as 1840. One of that date is in the Tower Armoury. Sir J. Turner, writing in the time of Charles I., says, “I do believe the word is corrupted, for I guess it is a German term, and should be ‘Donderbucks’; and that is,’thundering gun,’ Dander signifying thunder and Bucks a gun.” This was shortly after its introduction, and if we read “Dutch” for “German,” the derivation may possibly be correct. The barrel was commonly of brass. It does not appear to have been much used as a military weapon in England, but as a defence against housebreakers and highwaymen, and for the latter purpose carried by the guards of the royal mail coaches.

BOB-TAIL

Was the name given to “a kind of short arrow-head.” The steel of a shaft or arrow that is small breasted, and big towards the head.” (Halliwell apud Kersey.)

BOBBIN.

“A cord or twist of cotton, used to fasten portions of female attire.“ (‘Ladies’ Dictionary.’)

BODKIN.

A hair-pin. This well-known article of a ladies hair-dress has been used from the earliest times in England. Bodkins of bone and bronze have been found in early interments, and were used also for fastening the mantles of the Britons; but it is principally as an ornament for the hair that we find it in the catalogue of female attire. By the Saxons it was called a hairneedle: hæp-næol.

A bronze pin, supposed to be used for the hair, was discovered in a Saxon barrow on Breach Downs, near Canterbury. We subjoin an engraving the size of the original.

“He pulls her bodkin, that is tied in a piece of black bobbin.” (‘Parson’s Wedding,’ 1663.)

“A sapphire bodkin for the hair.” (J. Evelyn, ‘Mundus Muliebris; or, the Ladies’ Dressing room unlocked and her Toilet spread,’ 1690.)

“A silver bodkin in my head, And a dainty plume of feather.” D’Urfey’s Song of the Poor Man’s Portion.

The name was also given to a small dagger.

BOMBACE, BOMBASE, or BOMBIX.

Under which name it appears to have been known as early as the thirteenth century. Cotton from Bombay.

“Here shrubs of Malta for my meaner use,

The fine white ball of bombace to produce.”

(Halliwell, apud Du Bartas, p. 27.)

BOMBAST.

Stuffing for clothes, made of wool, flax, or hair, much used in the reign of Elizabeth and James.

“Thy bodies bolstered out With bombast and with bagges.” Gascoigne’s Fable of Jeronimo.

BOMBAZINE.

A stuff composed of silk and cotton, so-called from “bombax” or “bombix,” the ancient name for cotton. (See BOMBACE.) Bombazine was first manufactured in England in the reign of Elizabeth. “In 1575, the Dutch elders presented in court (at Norwich) a specimen of a novel work, called ‘bombazines,’ for the manufacturing of which elegant stuff this city has ever since been famed.” (Burns’s ‘History of the Protestant Refugees in England.’)

BONGRACE. (French.)

This article of female attire is described by Mr. Fairholt in his ‘Costume of England,’ p. 441, as “a frontlet attached to the hood, and standing up round the forehead, as worn by Anne Boleyn” in the engraving of her at page 243 of his work; and he quotes in support of this opinion, “Here is of our lady a relic full good: Her bongrace, which she wore with her French hood,” from Heywood’s ‘Merry Play between the Pardoner and the Frere,’ 1538; also from John Heywood’s ‘Dialogue of Proverbs’: “For a bongrace, Some well-favored vizor on her ill-favored race.“

The word “vizor” in the latter quotation is certainly in favour of his opinion, otherwise there is nothing positively to identify the bongrace with the stand-up border of the well-known headdress which antiquaries have, for want of reliable information, described as “the diamond-shaped head-dress.” It is at any rate clear from the first quotation, that whatever the bongrace was it was worn with the French hood, under which article we shall further inquire into the subject. In 1694 it is described as “a certain cover which children used to wear on their heads to keep them from sunburning, so called because it preserves their good grace and beauty.”

(‘Ladies’ Dictionary.’See CORNETTE.)

BONNET.

The word, from the French, bonnet, is now, except in Scotland, applied by us only to the well-known article of female attire, the introduction of which is of too recent a date to demand further notice in this work, beyond the record of the fact, that it was first made of straw, and succeeded the flat Gipsy hat towards the close of the last century. Straw bonnets were in full fashion in the year 1798.

Dictionary of Dress BY JAMES ROBINSON PLANCHÉ. THE DICTIONARY. Published by CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY, London 1876.