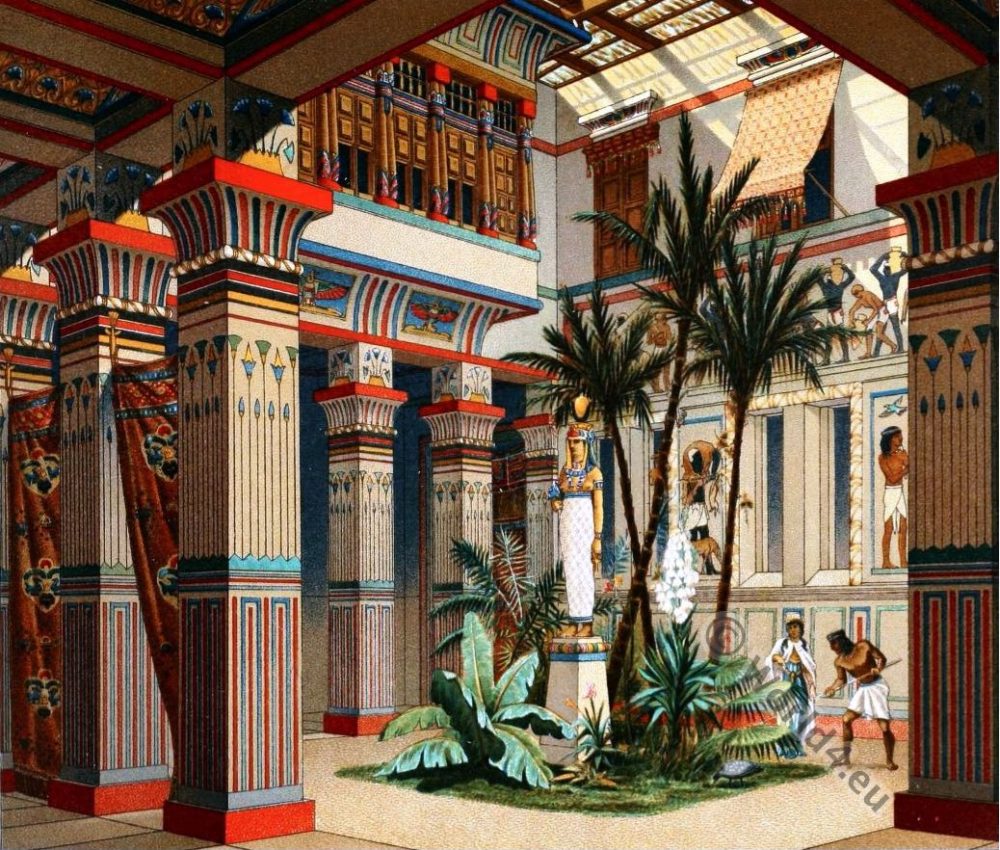

Ancient Egypt, one of the world’s oldest and most fascinating civilizations, traces its origins to around 3100 B.C. This era marked the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first Pharaoh, Narmer. The civilization flourished along the fertile banks of the Nile River as one of the world’s oldest and most fascinating societies.

Ancient Egyptian costumes hold a significant place in the history of fashion. Known for their intricate designs and symbolic meanings, these garments were more than mere clothing; they were an expression of status, identity, and beliefs.

Ancient Egyptians primarily used linen to create their costumes, owing to the abundance of flax in the region. Linen was highly valued for its lightweight and breathable properties, making it ideal for Egypt’s hot climate. The fabric was often bleached to achieve a white color, which was considered pure and elegant. Wealthier individuals adorned their garments with intricate beadwork, embroidery, and even gold thread, showcasing their social status and wealth.

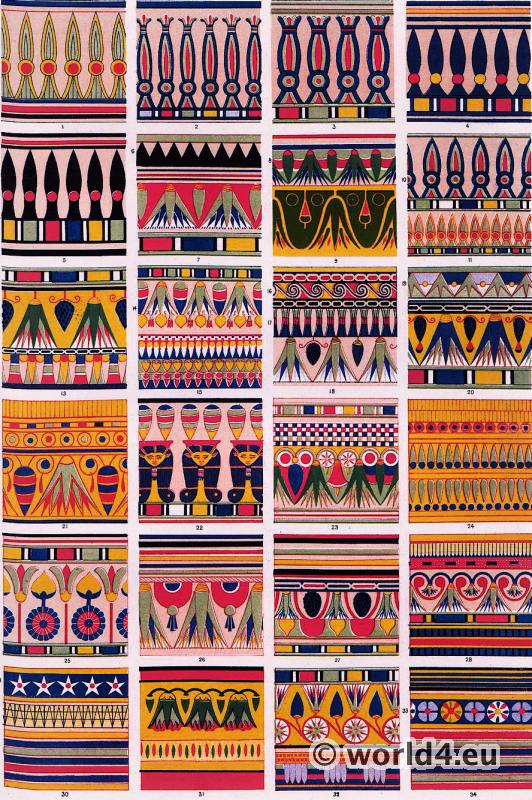

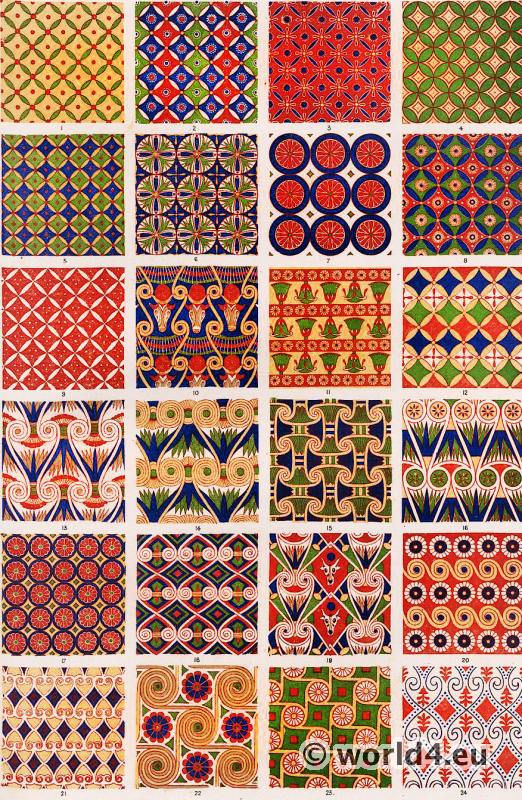

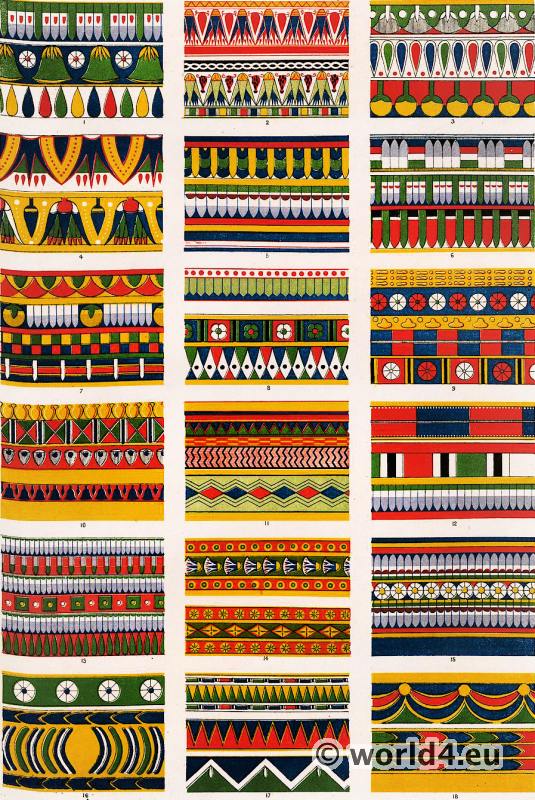

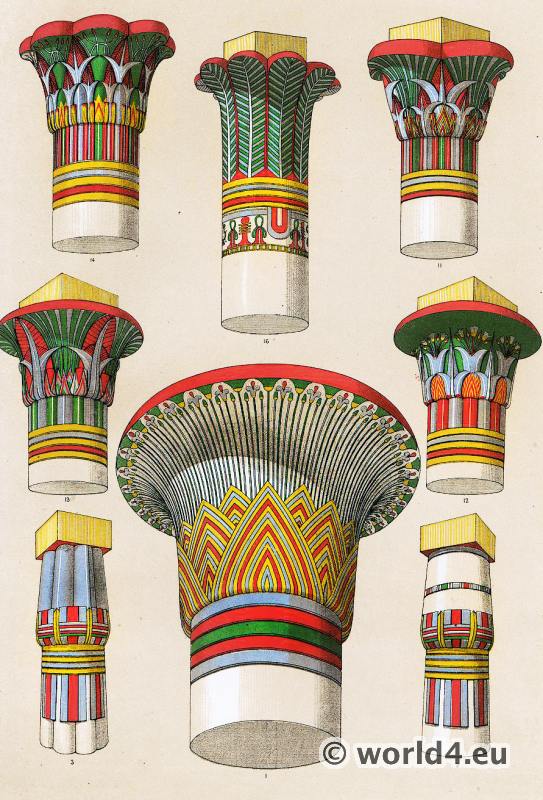

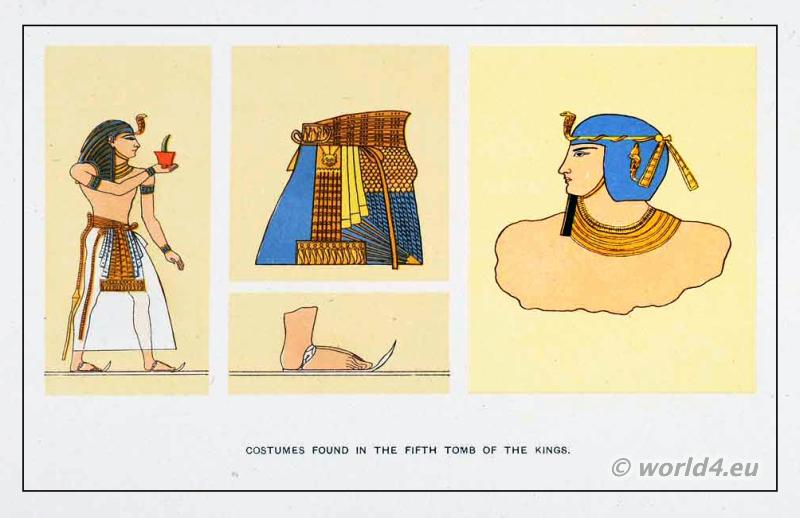

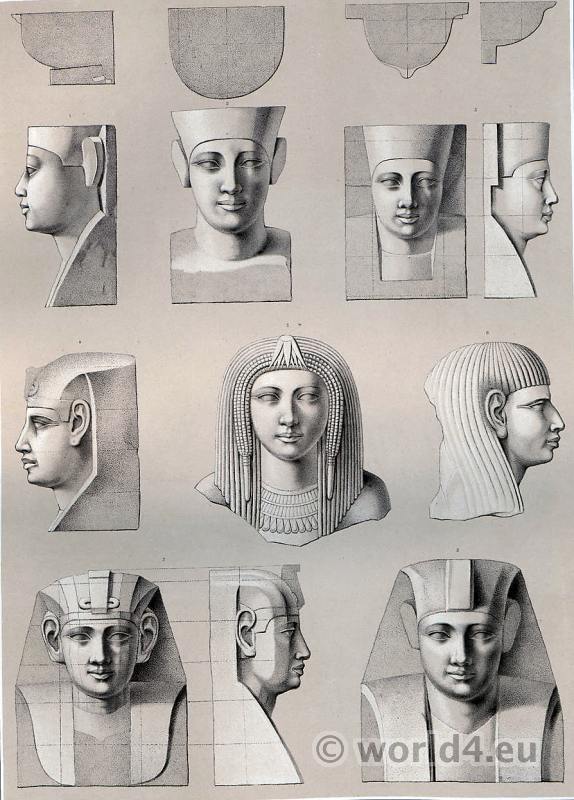

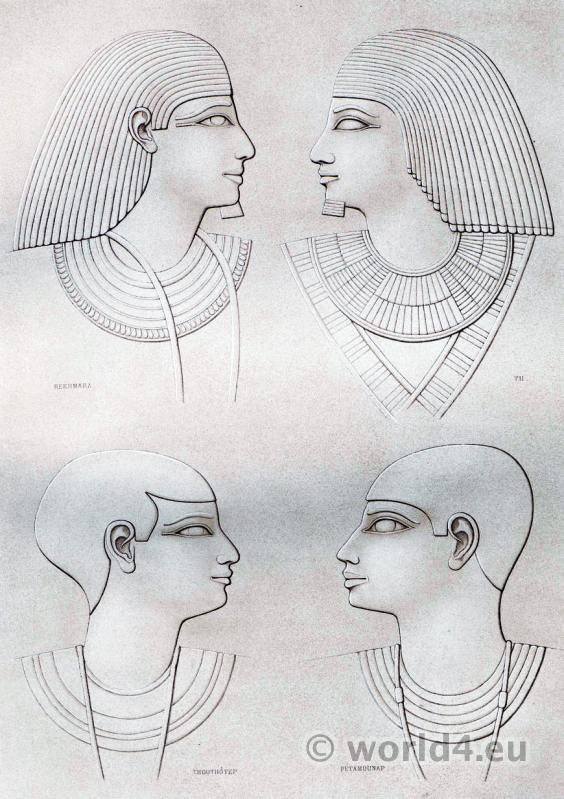

Though we find Egyptian costume in many instances decorated all over with woven or printed patterns, decoration in the main was confined to accessories such as the head-dress, collar, and girdle, these being often painted, embroidered, beaded, or jewelled. See various examples given.

The colouring which was usually, though not invariably, confined to the decorations consisted of simple schemes, variations of the hues of red, blue, green, yellow, and deep purple described on p. 6.

MATERIAL

The material used in the costumes was chiefly linen. In the most ancient types it was of a fairly thick, coarse weave; but in the later examples a fine thin linen, loosely woven so as to appear almost transparent, was used. The linen has often a stiffened appearance, and also gives the idea of having been goffered or pleated.

STYLES & SYMBOLISM

The styles of ancient Egyptian costumes varied according to social class, gender, and occasion. Men typically wore kilts known as ‘schenti,’ while women donned tight-fitting dresses called ‘kalasiris.’ Both garments were often complemented with cloaks and shawls for added elegance. The colors and designs were not merely aesthetic choices but also held symbolic meanings. For example, the color white symbolized purity, while green represented fertility and life.

RELIGIOUS AND CEREMONIAL ATTIRE

Religious and ceremonial attire in ancient Egypt was particularly elaborate. Priests and priestesses wore special garments that were believed to have protective and divine properties. These costumes were often decorated with religious symbols and hieroglyphs to invoke the favor of the gods. During important ceremonies and festivals, the Pharaoh and other high-ranking officials would don elaborate costumes to signify their divine authority and connection to the gods.

DATES

The earliest types of costume were the tunics; midway come the robes and skirts, and the draped or shawl type of costume appears the latest. However, the older types of costume did not disappear as the new ones were introduced, but all continued to be worn contemporaneously.

The dates of most of the costumes in this volume are given with their description, and have been verified at the British Museum.

SEE ALSO:

Clothing in Egyptian Old Kingdom. The Golden Age. The Ancient Egyptians themselves regarded the era as the Golden Age and the pinnacle of their culture.

Costumes of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt 2040 to 1782 BC. The Egyptian Middle Kingdom is often referred to as the feudal era. Most usually associated with the Pyramids, the Sphinx, and the Pharaohs.

Egyptian Costumes of the New Kingdom from c. 1550 to 1070 BC. Costumes of the Egyptian New Kingdom from approximately 1550 to 1070 BC.

Ancient Egyptian Costume History.

Decoration & coloring.

EGYPTIAN MEN AND WOMEN: THE DIFFERENCE IN THEIR DRESS

It can easily be gathered from the illustrations that the types of costume worn by both sexes were very similar. The high waist-line prevails in feminine dress, while the male costume, if girded, was generally confined about the hips.

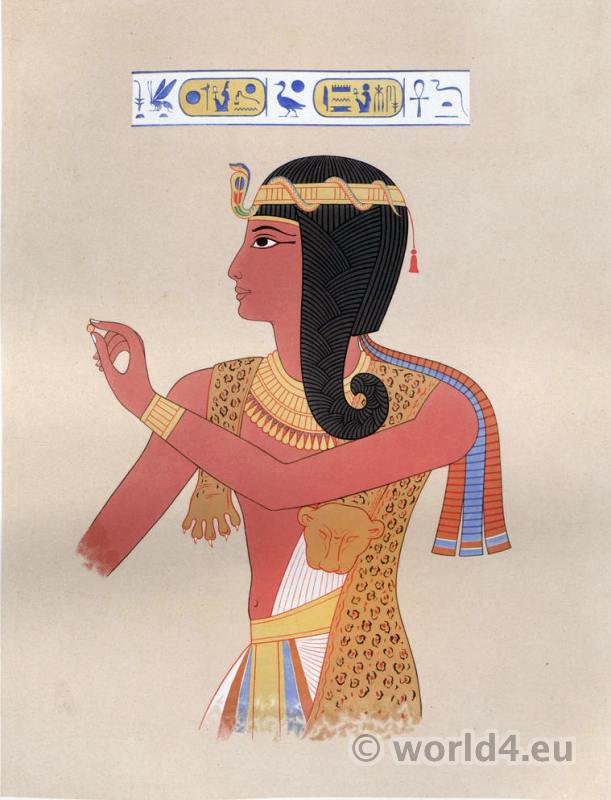

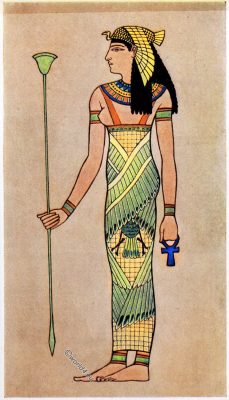

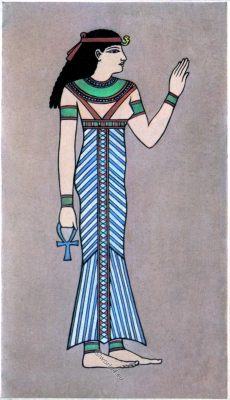

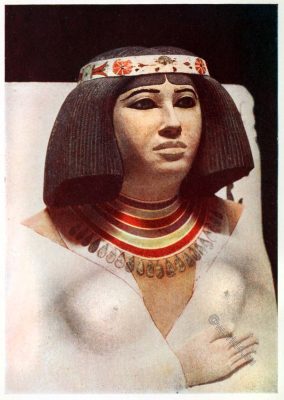

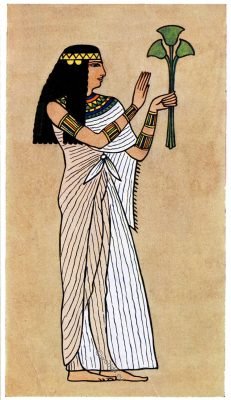

Plate 1. Ancient Egyptian Goddess

Plate I., which dates 700 B.C., is an exact copy of an Egyptian drawing. It will be noticed that the Egyptian method of representing the figure is a peculiar one.

A moderm representation of the same type of dress is shown in Fig. 2, and the plan of cutting in Fig. 2a. It should be noted that this plan—namely, a tunic with braces—is in some instances shown with the braces buttoned on each shoulder at the narrowest part.

This illustration is given as a type of Egyptian dress decoration, which would be either printed, painted, or embroidered on the garment. It might be considered that this type of dress more nearly approaches the skirt than the tunic; but reaching, as it does, to the breastbone and comparing various examples which, as it were, gradually merge into the sleeveless tunic which again merges into the tunic with short sleeves, the present classification will be found to be the most convenient.

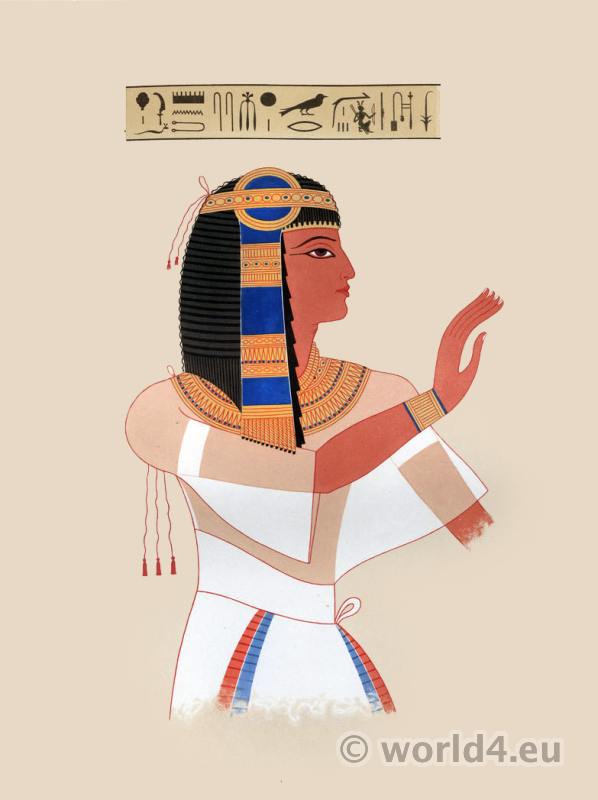

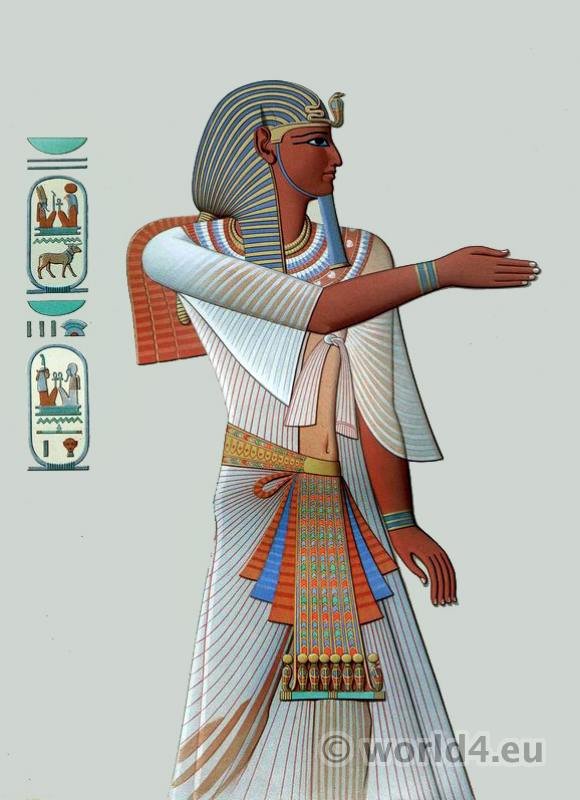

Plate II. Egyptian Queen

Plate II. which dates 1700 B.C. also first century b.c., is an exact copy of an Egyptian drawing of a woman wearing a species of tunic with braces (plan. Fig. 1).

The striped decoration upon this tunic is suggested by the lines of another type of Egyptian dress— namely, the drawn-up skirt.

The origin of the decoration can be easily understood by a reference to the drapery on Plate IX. In the original of this drawing the figure is represented with a lofty head-dress in addition to the fillet of ribbon and the golden asp here shown, but for the sake of getting the figure on a scale large enough to show clear details the head-dress is omitted. The person represented is said to be Cleopatra dressed as a goddess.

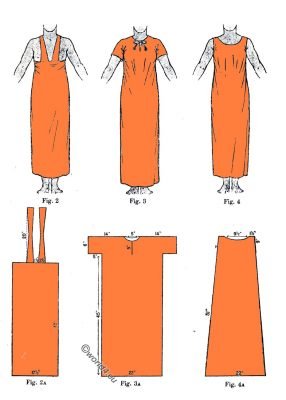

Figs. 2, 3, and 4, dating 1700, 1500, and 3700 B.C. respectively, are wearing dresses of the first great type of Egypt costume—namely, the tunic type. They were made of fairly thick linen. Fig. 2 is put on by stepping into it and pulling it up. Figs. 3 and 4 are put on over the head; the measurements given will fit a slim figure without underclothing.

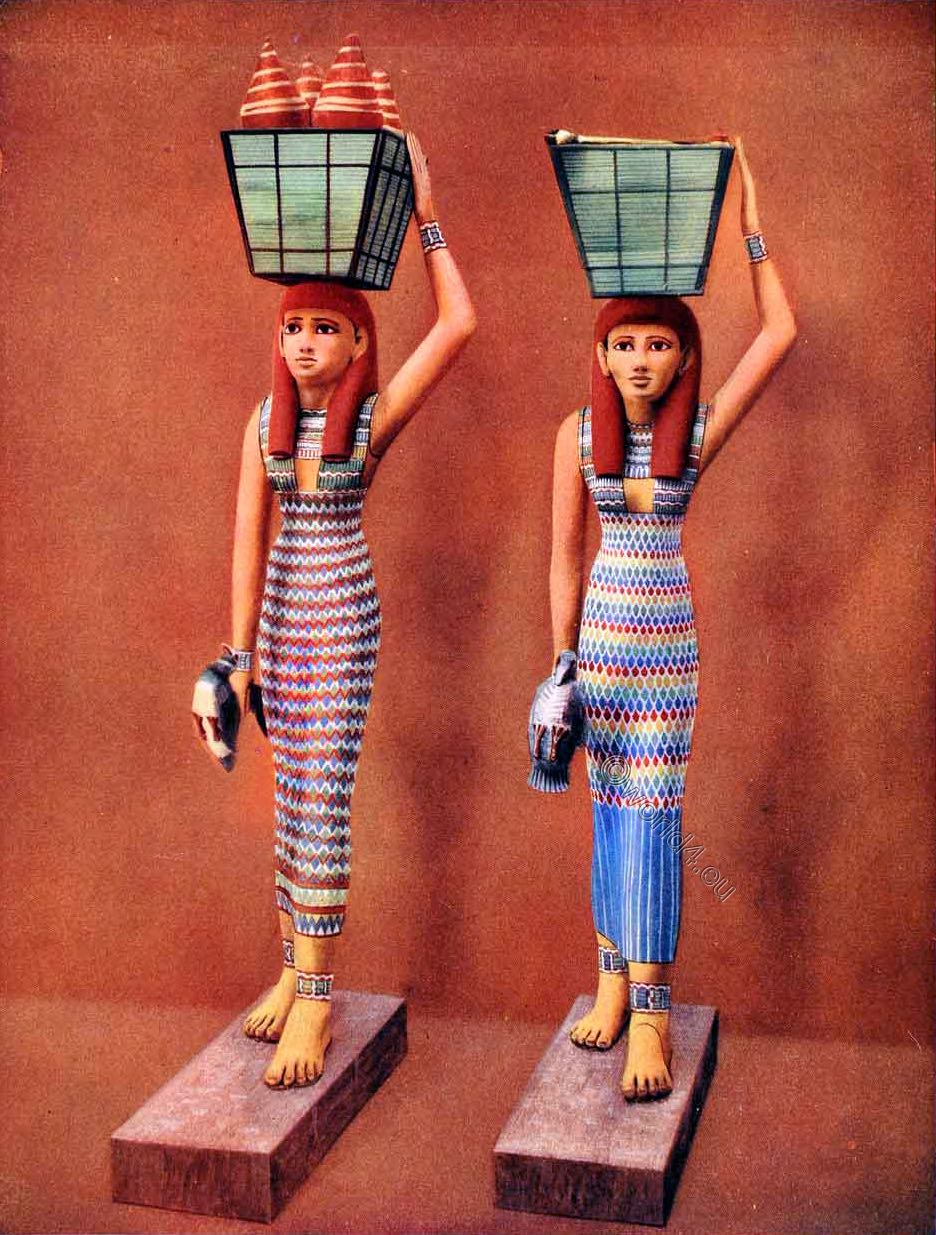

The origin of Fig. 2 was most probably a piece of linen of the same length as this garment but wide enough to lap about half round the figure and have a piece tucked in at the top to keep it closed. This sort of tight drapery is quite commonly worn by negresses in Africa to-day. We also find it on some ancient Egyptian wooden statuettes, the drapery being of linen while the figure only is in wood.

Plate III. Egyptian dress decoration

Plate III., It will be noticed that the Egyptian dress decoration is chiefly confined to the collar, which will be seen in wear on Plates V., VI., VIII., and X.

The patterns were either embroidered, painted, beaded, or jewelled; the favorite lotus flower is almost always in evidence in the designs (see a, b, c, and d on Plate III.)

On this plate also will be seen several other characteristic borders (f, g, h, i), and two all-over patterns (k, e), which were probably either stamped or tapestry-woven on the dress fabric.

The coloring of these patterns is chiefly taken from painted representations of persons and ornaments.

To arrive at the exact coloring used if the garments were decorated with dyed materials the description of the types of colors used in dyeing ancient Assyrian and Persian costumes, see p. 66, witch give a more exact notion of what was worn.

We have, in the British Museum, actual examples of dyed wools and colored beads used in dress decoration.

Plate IV. The God Osiris

Plate IV. belongs to the next great division of Egyptian costume, which may be called the “Type of the Robe.” This illustration shows it in its simplest form—namely, ungirded.

To understand the quaint Egyptian drawing of Plate IV. a reference to Fig. 5 is necessary, which is a modern drawing of the same costume. As will be seen from the plan.

Fig. 5a, this garment consists of a piece of material twice the height of the figure and folded over in the middle; a hole is here cut for the neck and, in addition, a short slit down the front to allow of the garment being pulled over the head.

The material is sewn up the sides from the bottom, leaving a space at the top for the passage of the arms. A garment similar in type to this is worn at the present day in Egypt and Syria, and also, strange to say, by the natives of Brazil.

This robe should be compared with that worn by Darius, King of Persia, later in this volume.

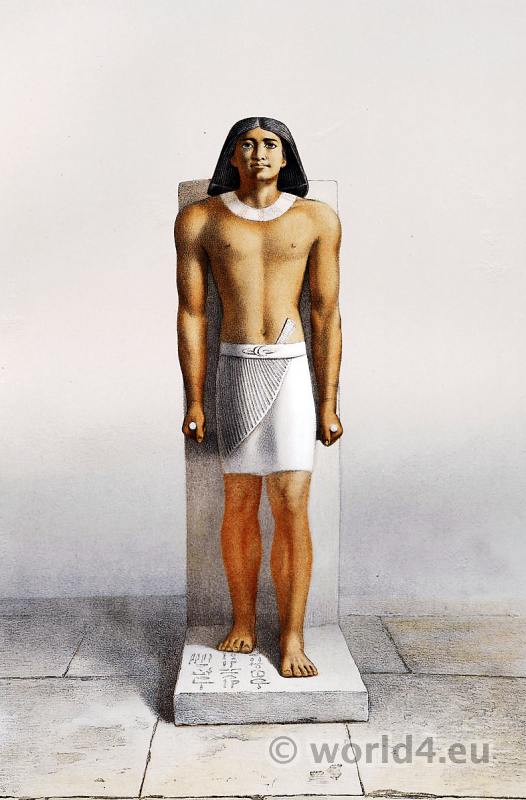

Plate V. Ani, A Scribe.

Plate V.,dating 1450 B.C., shows the same robe as Plate IV. worn in a different manner. In this case the garment is left open down the sides, the front half is taken and pinned at the back of the waist, and the back half is drawn towards the front and girded with a wide sash measuring 32″ x 120″, as shown in Plate V. and Figs. 6, 7, 8, and 9.

It should be noted that Fig. 6 is a modern drawing of Plate V. which dates 2500 B.C., gives three different views of the same dress Fig. 7-9, a costume which emphasizes the love of the Egyptians for drawing up the dress tightly so as to define the limbs at the back and allowing great masses of drapery to fall in front to the feet.

To adjust the sash or girdle on Plate V., commence at the right side of waist drawing the sash downwards to the left and round the hips at back, next draw upwards across the front from right to left and round waist at back and tuck the remaining length of sash in front as shown in Fig. 6.

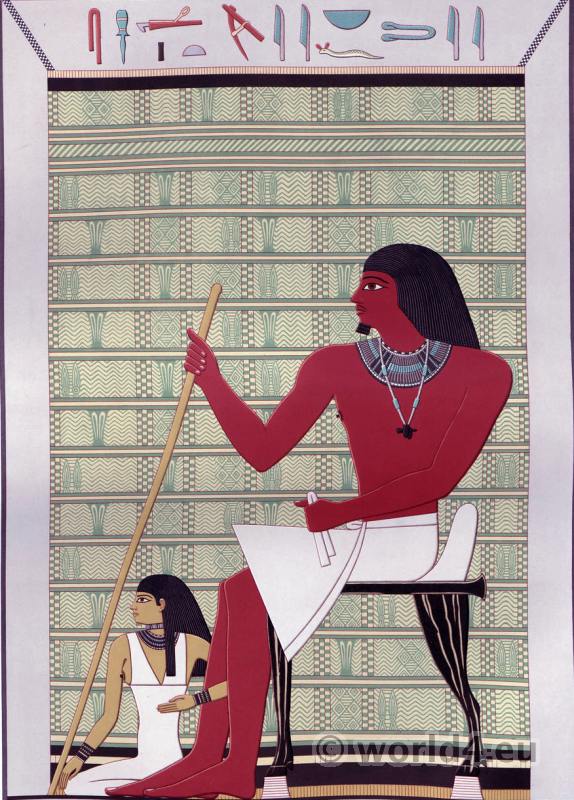

Plate VI. Thuthu, Wife of Ani

Plate VI. is an illustration of a robe worn by a woman 1450 B.C., and Fig. 10 is a modern representation of the same robe. It will be noted in this case that the front half is not pinned behind the back, but is kept quite full in front, and that the back half, instead of being girded by a sash, is drawn round and tied in a knot just under the breast.

This robe on women is also sometimes tied with a narrow girdle under the breast instead of the edges being knotted.

Plate VII. EGYPTIAN DECORATION

Plate VII. The decoration on this plate shows the detail of the characteristic Egyptian winged globe (a), hawk (b), and beetle (scarabaeus). Plates I. and VIII. are examples of the application of winged decoration upon Egyptian costume.

Three other geometrical borders (d, e, and f) and two all-over patterns (g and h) are given; g shows an example of the well-known feather or scale pattern; h (which is similar to e, Plate III.) is a favorite geometric motif, and was often printed or painted on garments.

A very charming effect also of this pattern was a tunic entirely composed of beads, or beads and reeds, and worn over the garment shown on Fig. 2. Several beaded networks of this type may be seen on the mummies in the British Museum.

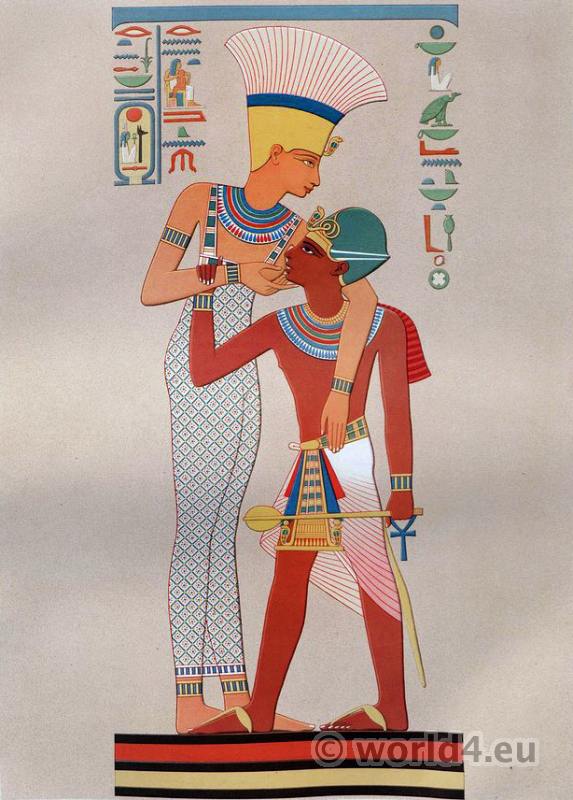

Plate VIII. Ancient Egyptian Queen

The third outstanding type of Egyptian costume may be described as the “Type of the Petticoat and Cape,” (the petticoat was sometimes worn without the cape).

Now this petticoat or skirt, as shown in Plate VIII. and Fig. 11, consists of a straight cut piece of material threaded through at the waist with a narrow strip which is knotted round the figure to keep the garment in position; the cape-like shoulder drapery is an oblong piece of stuff, to drape which take the corners d and e of Fig. 11a, in your hands and twist them till the triangles a, b, c, and d, e, f, have become cords, and then knot as shown in the diagram.

In the skirt piece, Fig. 11b, sew together the two short sides. As will be seen in the illustration, a long knotted girdle about 100 inches in length is worn over the skirt. It passes twice round the waist, and is knotted at the back as well as the front. In Plate VIII. the deep ornamental collar is worn over the cape.

The collar, which was fastened down the back, is shown in plan (Fig. 11c). Fig. 12 shows another method of wearing a similarly cut but rather longer skirt; in this case there is no waist cord; two pieces of the upper edge about half a yard apart are taken in the hands and twisted, one is crossed over the other and tucked inside, the other is pulled up and forms an ear, as shown in sketch. This particular draping is the inspiration of the decoration on Plate II.

Similar drapings without the twisting were worn both by men and women. It is interesting to note that a practically similar garment is worn in Burma at the present day by both men and women.

Plate IX. Egyptian Decoration

The noteworthy details of the decorations on this plate are those illustrated at a. and b. These are appendages from girdles such as worn by male figures; an example is Fig. 21.The material of this appendage may be possibly of painted leather, wool Embroidered linen, or linen with metal mounts. Many beautiful painted illustrations of this girdle appendage are to be found in the British Museum; e is from a feather fan.

Read more:

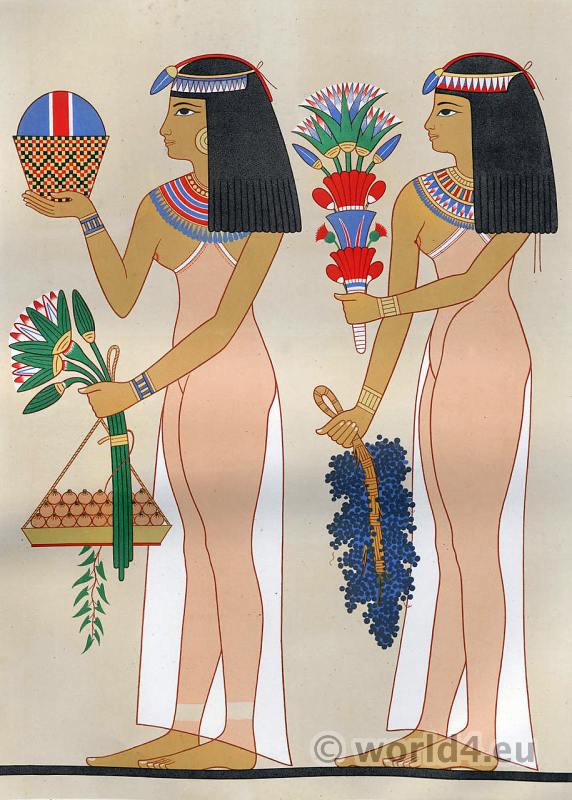

Fig. 13 is an Egyptian woman’s costume dating 1450 B.C.; she is wearing two garments—namely, a skirt and cloak. This skirt, which is frequently worn alone without the cloak, as shown in Fig. 12, is cut to exactly the same width top and bottom. It is wide for the figure, and the superfluous fullness is caught up in each hand in the act of putting on.

The upper edge of garment is drawn tightly round the figure just under the breasts; the portions held in each hand are then tied together in a knot. In Fig. 13 the cloak is knotted in with the skirt; this cloak is simply a rectangular piece of material.

It will be noted that Figs. 13, 14, and 15 all show the popular Egyptian effect of drapery drawn tightly round the back of the limbs and falling full in front.

Fig. 14, which dates a.d. 200, shows a Roman adaptation of the same costume. The figure wears underneath a long tunic, and over this, tightening it in at the waist, an Egyptian skirt; a small Egyptian scarf is knotted to the skirt in similar fashion to the costume in Fig. 15.

All the garments worn by Fig. 14 are rectangular pieces of material; the tunic is two straight pieces of stuff sewn up the sides; the top edge is divided into three parts by pinning; these openings form the neck and arm-holes.

Fig. 15 is a Greek costume of the fourth century b.c. in which the Egyptian influence is equally strongly marked; in this case, again, the garments are all rectangular pieces of material, the sleeves in one with the tunic.

To knot the cloak to the over-skirt, as shown in this figure, the fullness of the over-skirt should be bunched up in one hand; the two corners of the cloak are taken in the other hand and twisted together round the skirt in a knot.

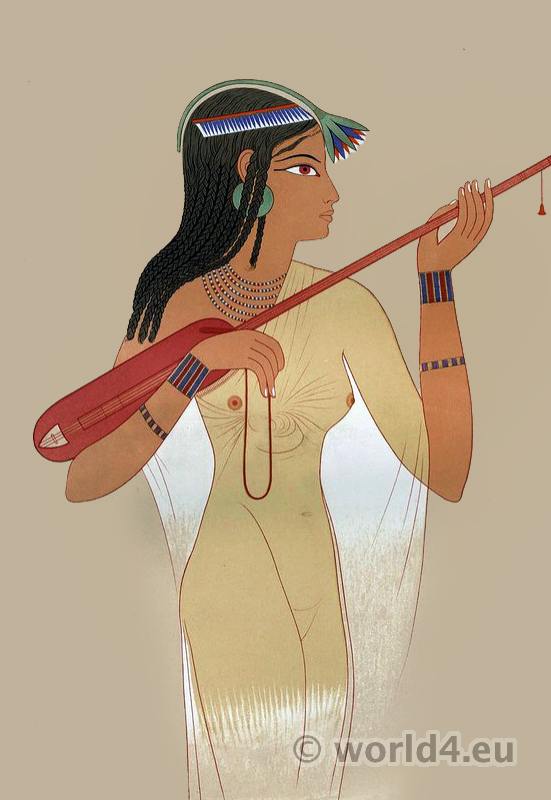

Plate X. Ancient Egyptian Priestess

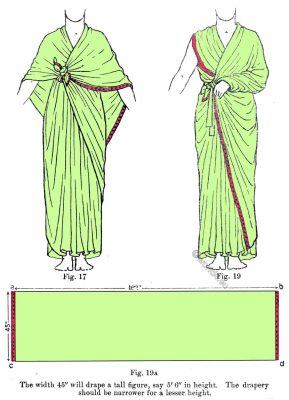

Plate 10. shows the fourth division of Egyptian costume — namely, the “Type of the Shawl or Drapery.” Several varieties of this type are illustrated. The fourth division of Egyptian costume is shown in the examples on Plate X. and Figures below. These are the draped or shawl type of costume.

Different types of Draping

They have many resemblances to the draping of the well-known Indian sari of modern times. Compare these with illustration of sari. The ingenuity displayed in the draping of these costumes can only be realized when they are actually done upon a model. It should be noted with regard to all Egyptian costumes of the more fully draped type that the entire draperies seem to radiate from one point, usually a knot at the waist, with very beautiful effect.

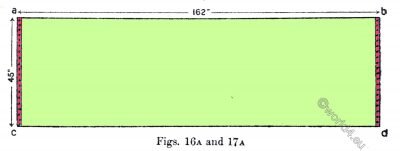

To drape Fig. 16 which is a modern drawing of Plate 10., tie a cord round the waist, tuck in comer b (see plan. Fig. 16a) at left side of waist, pass round the back and round the right side to front again; make some pleats and tuck them in in centre front of waist, then pass round back again to right side; catch up the whole drapery and throw it upwards from right-hand side of waist under left arm-pit, pass on round the back and over the right shoulder towards front, then throw the remaining portion of garment across the chest and backwards over the left shoulder; take corner a and bring it round under right arm-pit, release corner b which you first tucked in, and tie it to “corner a.

The corner c will hang down in a point at the back.

To drape the costume on Fig, 17, which dates 1300 B.C., take the corner a of Fig. 17a and hold it at right side of waist in front, pass round the back and round the left side to front again, tuck in some pleats in centre front, and pass on round the back to left side of waist under left arm towards the front; ‘catch up the entire garment and throw over the right shoulder, pass the upper edge of the garment round the back of the neck and over the left shoulder and downwards across the breast to right, where the corner b should be tied to corner a. Corner d hangs down in a point at the back.

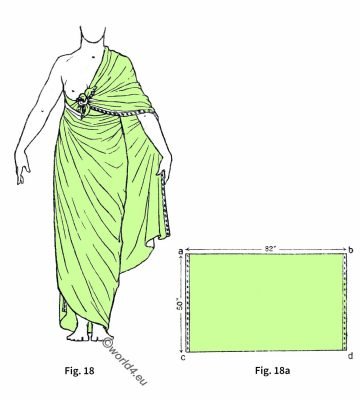

For Fig. 18, which dates 1600 B.C., take the corner a of Fig. 18a and hold it at right side of waist in front, pass the edge a-b round back of waist to the left side and across the front of waist, pass it round the right side again under the right arm towards the back and upwards over the left shoulder; tie the corner a to corner b in front.

For Fig. 19, which dates 550 B.C., tie a waist cord, hold corner a of Fig. 19a at left side of waist in front, and throw the whole garment upwards over the right shoulder to the back; take the comer c, bring it round under the right arm, and hold it along with the comer a; draw the edge a-b, which still hangs over the right shoulder, downwards across the back to left side of waist.

Bring it round to front of waist and pin it to the corners a and c at the left side of waist in front, passing the garment on round the front; tuck in a few pleats in centre front into the waist cord, then pass it round right side of waist and upwards across the back over the left shoulder, downwards across the breast to right side of waist; here pass a loop of material over the left wrist as shown in diagram; now pass a girdle round the waist over the entire drapery, knot it at right side of waist, confining the drapery as illustrated in Fig. 19.

Draping of a Cloak

Here are three other varieties of Egyptian costume. Fig. 20, which dates sixth century B.C., is an arrangement of a cloak worn by a man (Plan 20a).

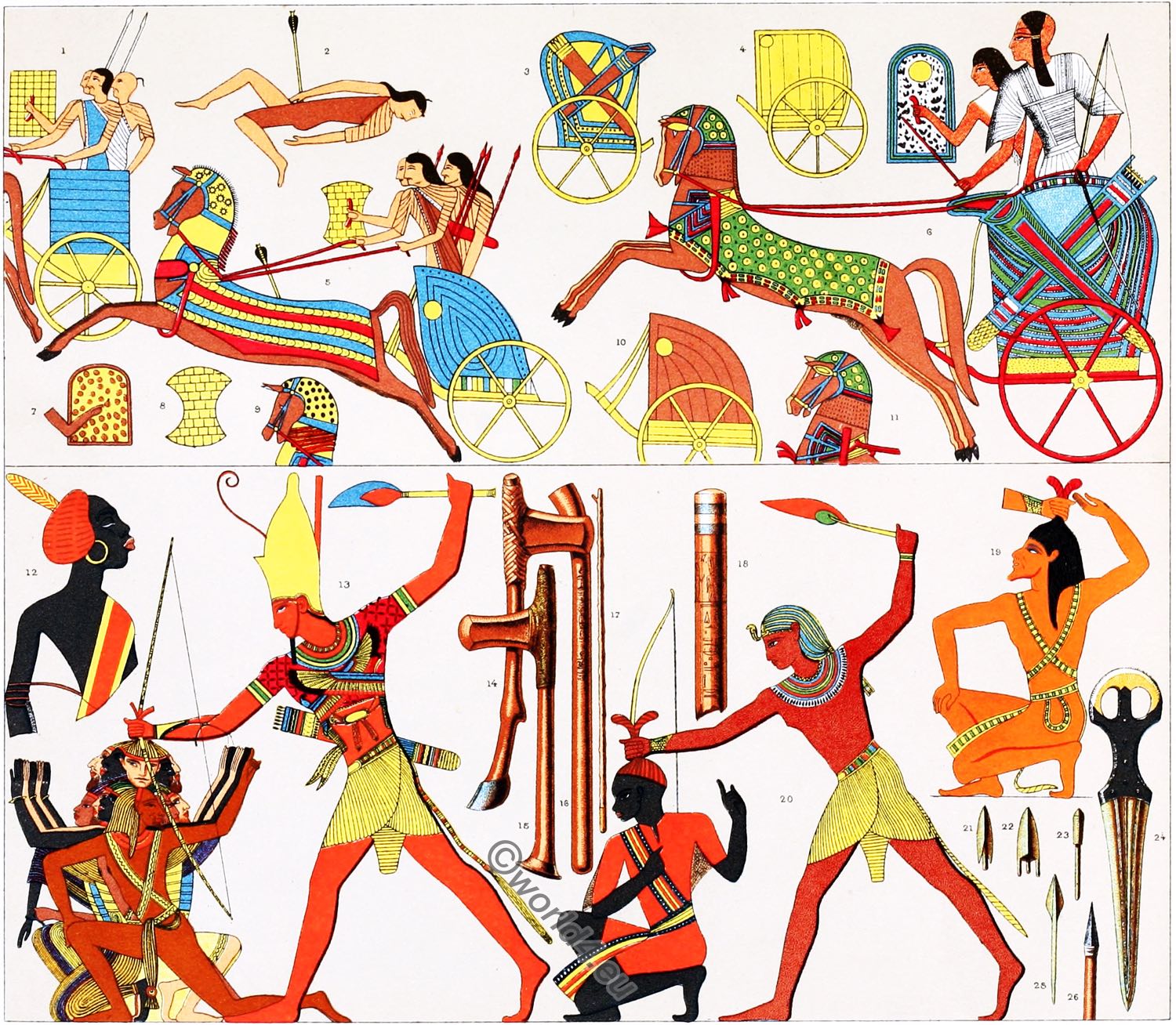

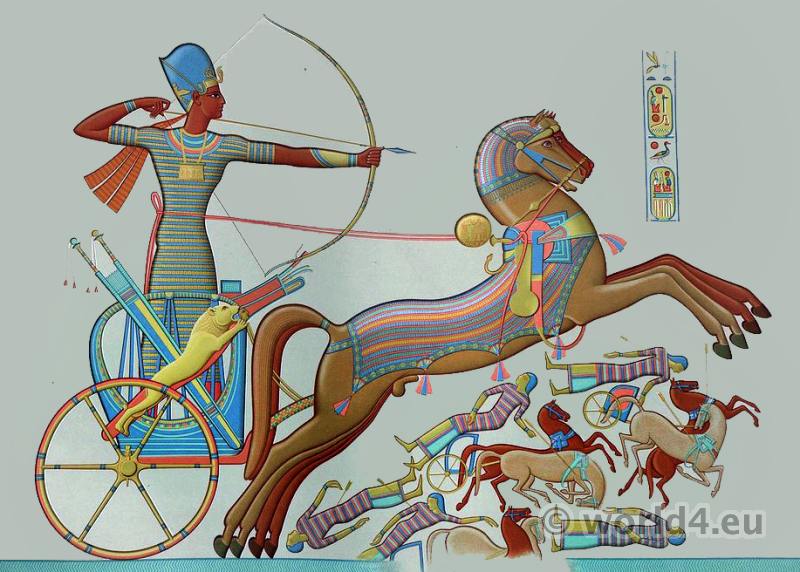

Fig. 21 shows an interesting cross – over garment sheathing the upper part of the body, worn by a Warrior King, 1200 b.c. It was probably made of leather or quilted linen (plan, Fig. 21a).

This figure is also wearing one of the characteristic belts with appendages (for detail see Plate IX., a and b). Fig. 22, which dates 1300 B.C., is wearing a robe, as previously described on Fig. 6, but in addition has a stiff corselet (Plan 22a) of leather or quilted linen which is fastened at the side; the date of this figure is 1300 B.C..

THE KALASIRIS

To judge from the most ancient representation that we possess, the Egyptians of the Old Kingdom (c. 3000 B.C.) wore a loincloth made of woven material, which was wrapped several times round the body and kept in place by a girdle. In addition to this a wrap or a speckled skin was hung over the shoulders.

This costume continued right up to the time when the so-called Old Kingdom reached its highest brilliance, and the beauty and costliness of material and draping were the only marks that distinguished monarch and nobles from the lower classes.

By and by another item of dress was added-a somewhat close-fitting, one-piece skirt of expensive material, which was similarly fastened by means of a girdle.

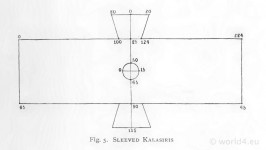

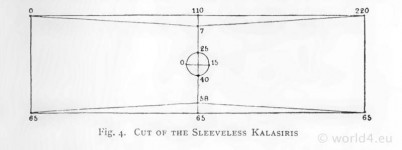

The so-called kalasiris (Figs. 4-5), a garment for both sexes, which was introduced shortly after the establishment of the New Kingdom (c. 1000 B.C.), was a long robe quite unlike those just mentioned, differing from them both in cut and in the materials of which it was made.

There was apparently more than one style of this garment. It was either a coat covering the body from the hips or the procardium to the abdomen, supported by a band passing over one shoulder, or it even reached as far up as the neck. Some forms of it were sleeveless while others had short and narrow or long and fairly wide sleeves.

This garment also varied in width. Sometimes it was wide and full, sometimes so close-fitting that it is difficult to understand how the wearer could walk.

Most probably, therefore, there were two ways of making the kalasiris. Either it was woven or knitted in one piece so as to impart to it some elasticity and cause it to cling closely to the lower limbs of the wearer even when he moved; or it was made of pieces cut separately and sewn together at the sides. In the former case it resembled a narrow bag of the same width throughout its whole length, sometimes with sleeves fitted to it or knitted in it.

This elastic type of kalasiris seems to have been made of material which was in most cases of close texture, but occasionally very loose and transparent. It is of course possible that the transparency was due to the stretching of material that was originally close in texture and to the consequent tearingof the threads or stitches.

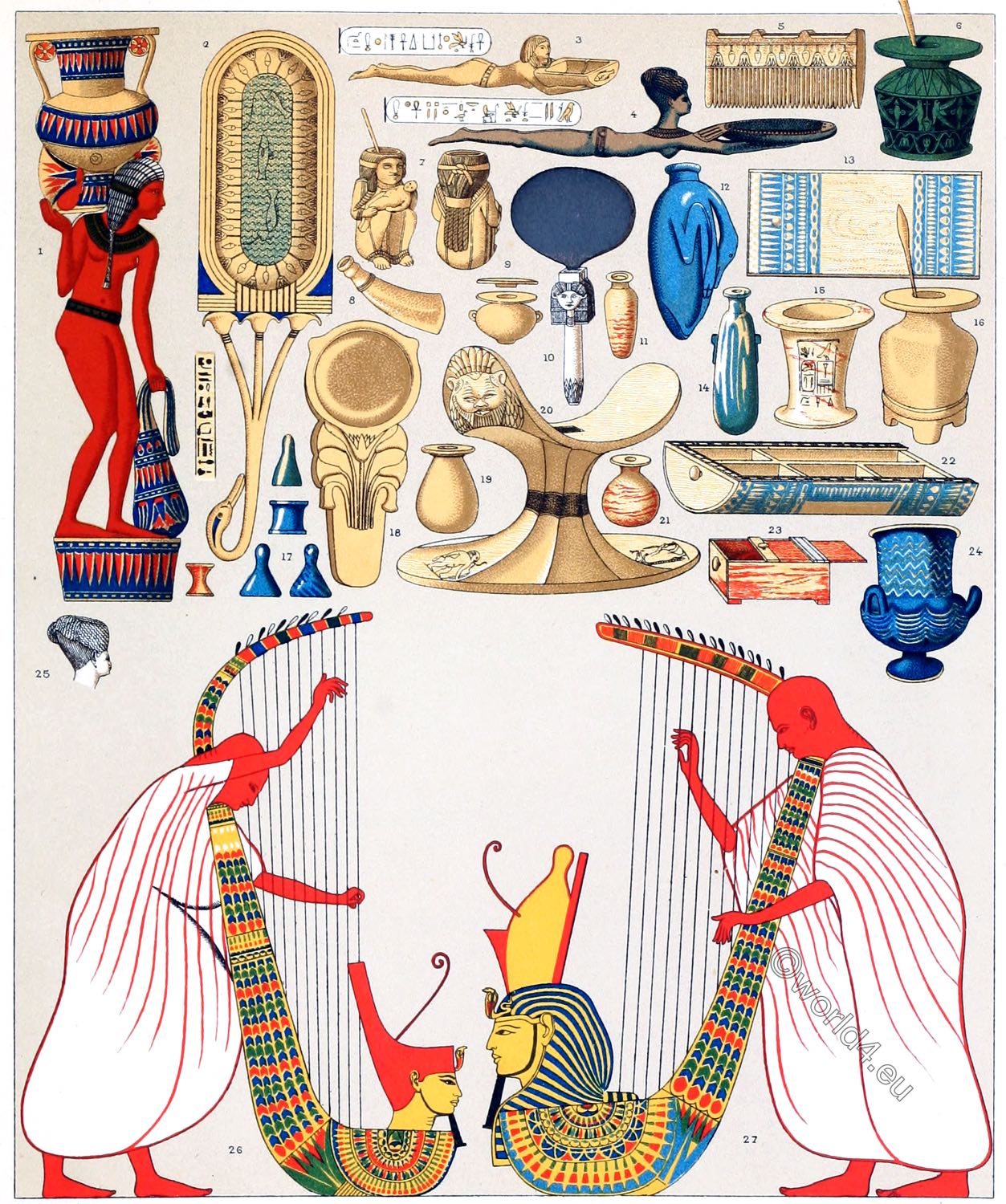

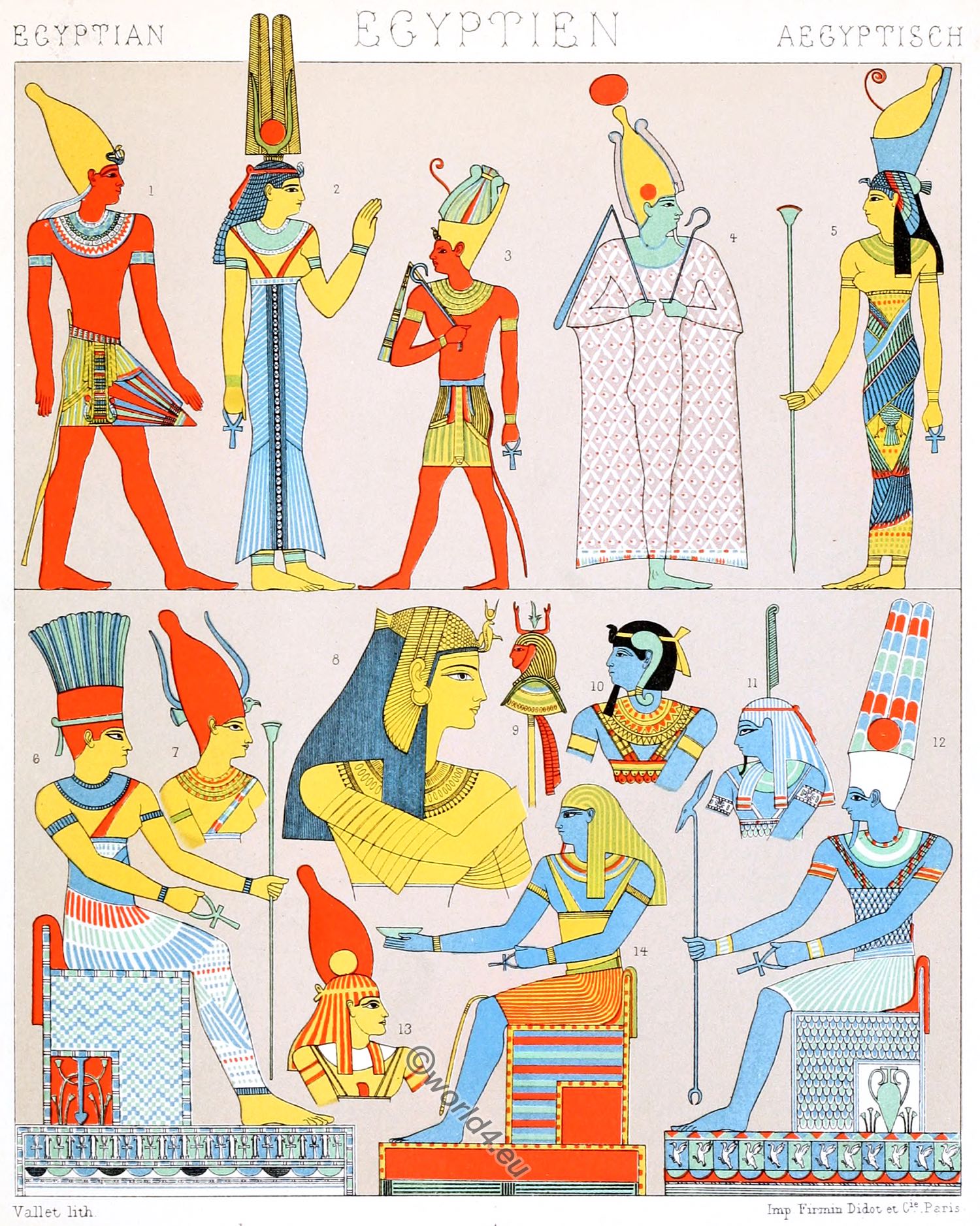

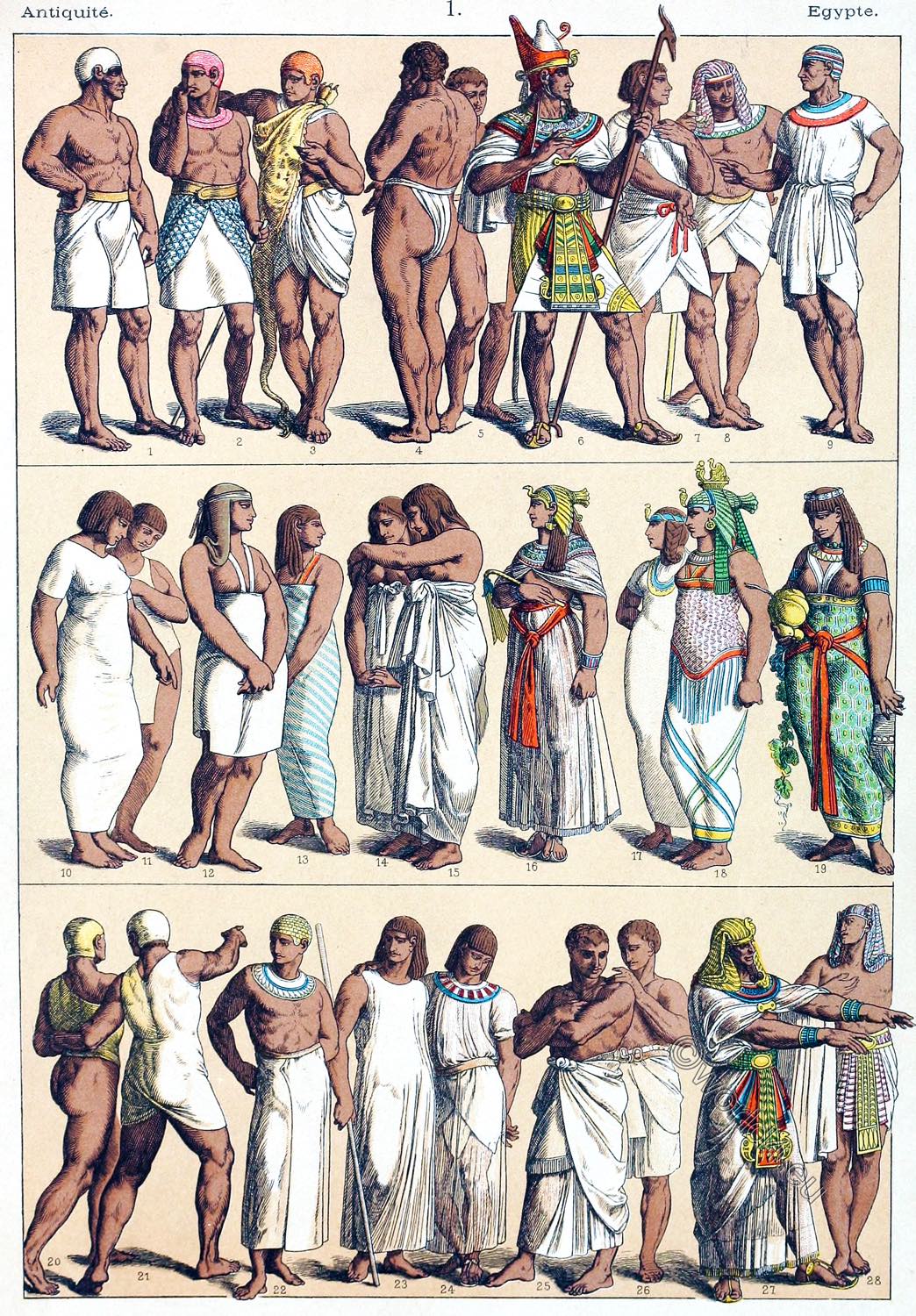

Costume plates: The ancient Egyptians by Friedrich Hottenroth.

- The Old Kingdom (3rd to 6th dynasty) lasted from about 2700 to 2200 BC and is the oldest of the three classical periods of ancient Egypt.

- The Middle Kingdom (11th to 12th dynasty) is defined as the state in Ancient Egypt that existed from around 2137 to 1781 BC and marks the second peak of the centralised Egyptian state.

- The New Kingdom (18th to 20th dynasty) covers the period from 1550 to 1070 B.C. and is, along with the Old Kingdom, probably the most famous epoch of the Pharaonic period. One also speaks of the age of the Egyptian empire or the imperial phase. According to the sources, the history of this epoch is particularly well documented.

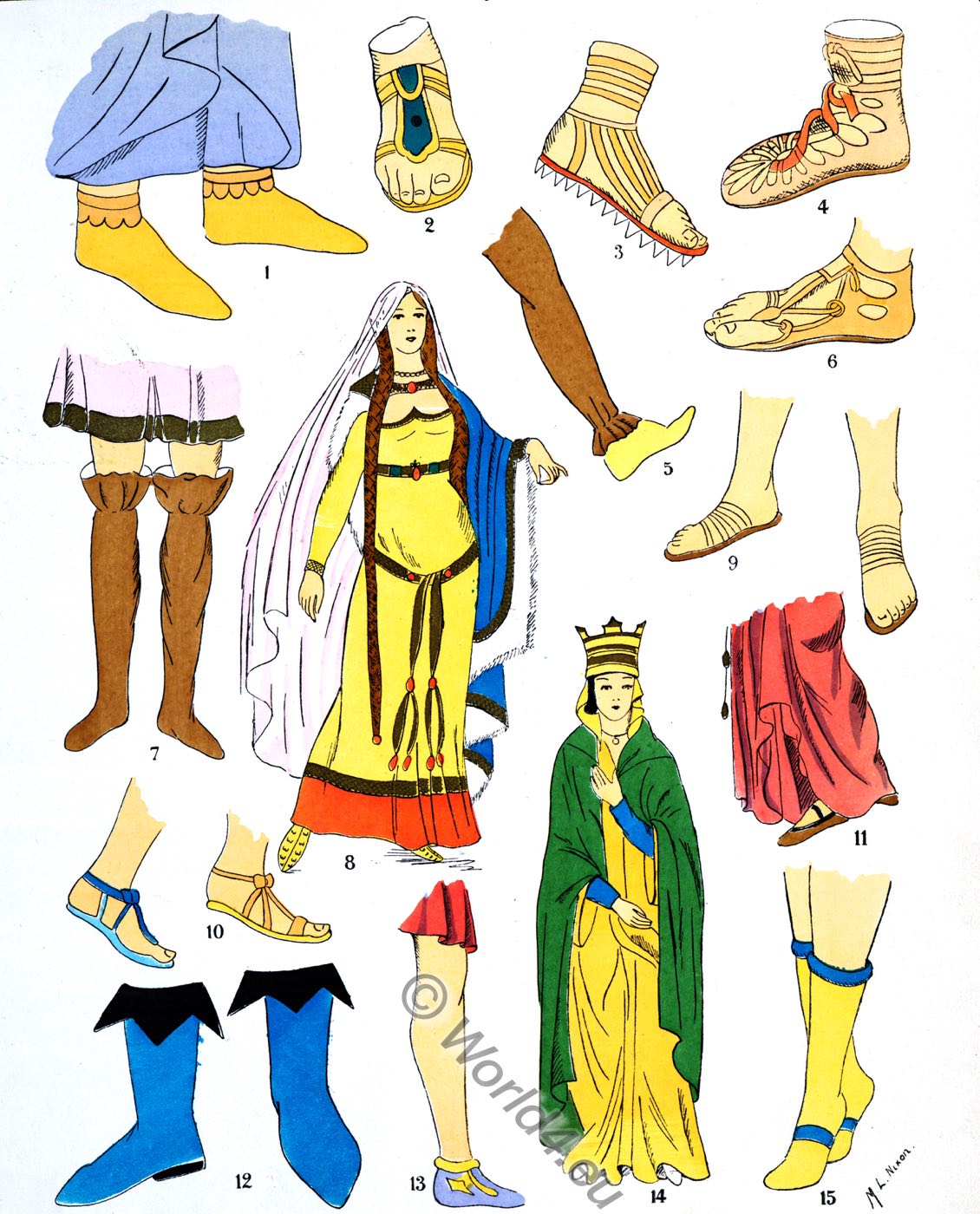

Plate 1. Egyptian.

- Nos. 1-5, 8, 22, 26 – Men from the old empire;

- Nos. 6, 28 – Kings from the old empire;

- Nos. 7, 9, 23-25 – Men from the new kingdom;

- Nos. 10-15 – Women (old empire);

- Nos. 14, 15 – Women in mourning;

- Nos. 16 -18 – Queens (old empire);

- Nos. 19 – Noble women (old empire);

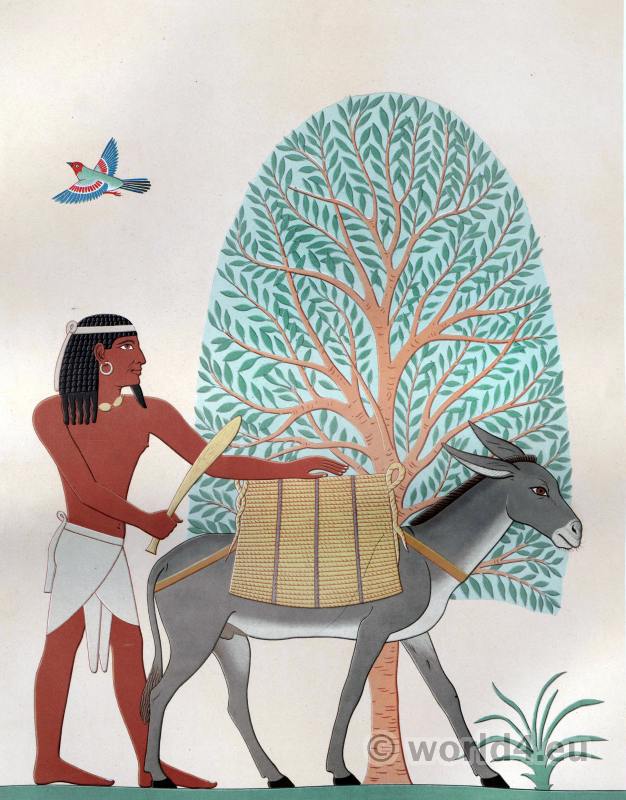

- Nos. 20, 21 Workers (new kingdom);

- No. 27 – Egyptian king (Pharaoh).

Plate 2. Egyptian.

- Nos. 1, 2 – Men of the people (new empire);

- Nos. 3 – Chief priests (new empire);

- Nos. 4, 7 – High officials;

- No. 5 – Umbrellas;

- No. 6 – King (new kingdom);

- No. 8 – High priest (old empire);

- No. 9 – King in war dress (old empire);

- No. 10, 11 – Commander;

- No. 12, 14, 15 – Noble women (new empire);

- No. 13 – Queen (old empire)

- No. 16 – Priestess of Isis (new empire);

- No. 17 – King with entourage, going out to war.

Dress of Egypt Pharao

The sewn type of kalasiris was a short garment somewhat resembling a woman’s petticoat. The width of the material determined the length of the garment, so that there was only one seam. The numerous folds were distributed at equal distances round the body. In some instances it was worn in apron fashion, and in that case it was not sewn at all.

The long type of kalasiris that covered the body up to the neck was made from a rectangular piece of material twice as long as the garment (see Fig. 4). It was folded in the middle, and a hole was cut out to allow the head to pass through.

The sides were then sewn together, gaps being left unsewn at the top to serve as armholes. When the garment was meant to be worn without a girdle the cut was slightly altered so as to make the material over the shoulders narrower than that lower down. This is indicated by the interior lines in Fig. 4.

For the sleeved kalasiris the sleeves were either cut separately and sewn on or a slight change was made in the garment itself (Fig. 5).

The material on both sides of the opening for the head was left as wide as the intended length of the sleeves. The lower edges of the portions forming the sleeves were sewn together when the sides of the garment were sewn.

The clothing of Egyptian women covered and concealed the person to a far greater extent than did the clothing of the men. The close-fitting, elastic type of kalasiris was the ancient national costume of the female population of the country.

There were slight variations of style, but in all cases the garment was long enough to cover the ankles. In some it extended up to or beyond the breast (being held in place by shoulder straps), or even up to the neck. This last style was provided with sleeves.

The working class

The working class wore the same style of garment. In order to obtain greater freedom of movement they adopted various methods of tucking it up, and wore it much shorter than the upper classes did. In addition to the garments described above, various kinds of capes were worn both by men and women of the upper classes.

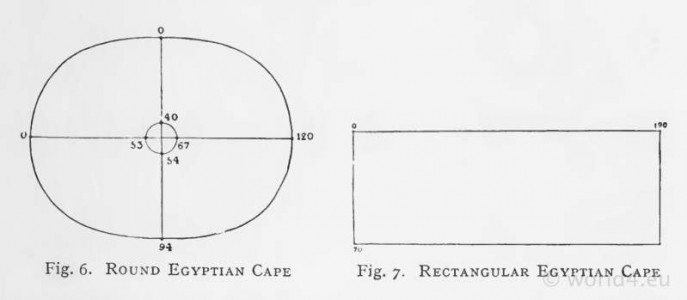

The earliest type, which was in regular use as far back as the time of the Old Kingdom, was an almost circular shoulder-cape (Fig. 6), either closed or made to fasten behind. It varied in width, but never reached lower than the shoulder, and was made either of linen painted in diverse colours or of very costly network.

Another style of cape, made only of transparent materials, fell from the shoulders to a little below the elbows. This cape was either almost circular in shape, with a hole in the centre to allow it to be passed over the head (Fig. 6), or rectangular (Fig. 7).

In the latter case the strips forming the cape were laid over the shoulders, gathered on the breast, and held in place by a clasp, so that the ends hung down loose.

In putting on the almost circular cape just mentioned the narrow sides on breast and back were gathered, thus giving rise to diagonal folds. As in the case of all ancient dress, the most important feature of the dress of the Egyptians was the draping.

Each people had its own characteristic way of putting on garments that closely resembled each other in cut and style.

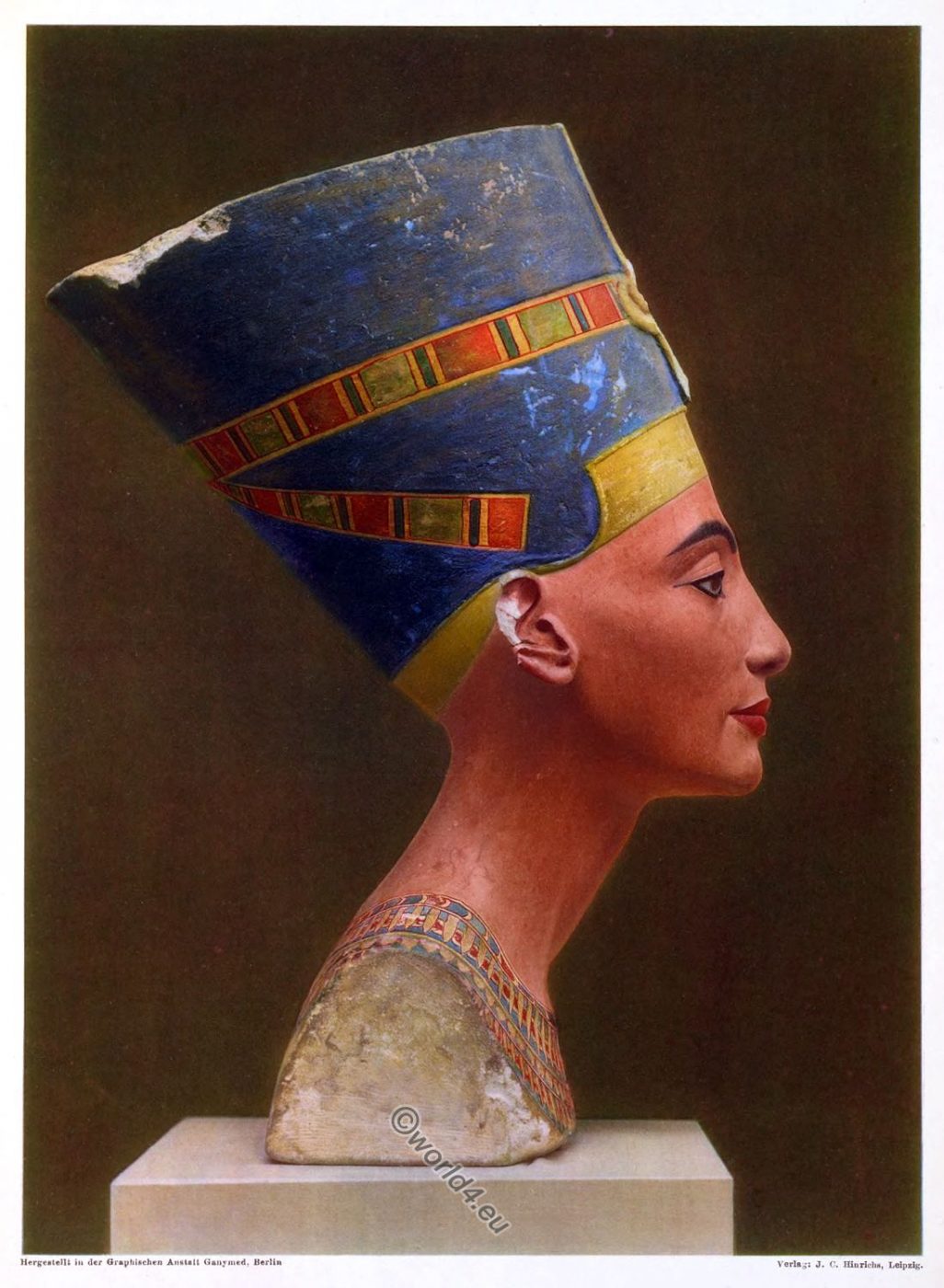

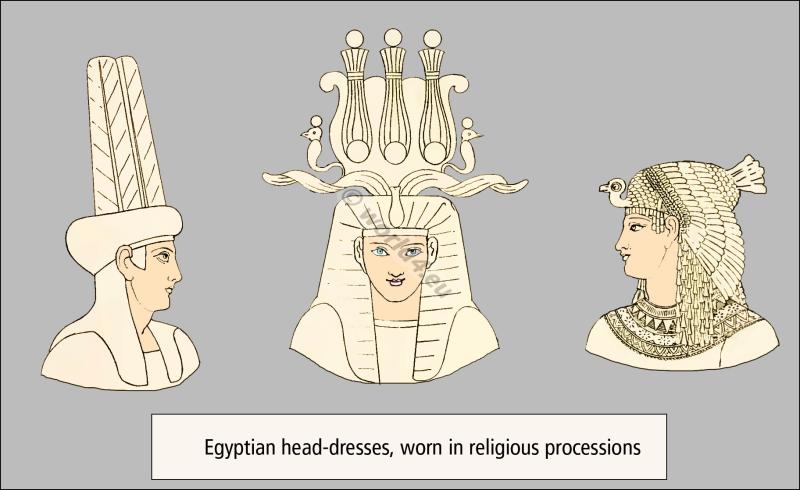

Egyptian head-dresses. The Blue or war crown.

The Blue Crown or war crown, the Cheperesch, Part of the regalia of the child gods and kings (pharaohs). Worn by the Pharaoh on certain occasions and often in battle. Symbolically served the crown probably the renewal and fertility.

It was considered a sign of the rightful heir to the throne, who makes his claim law.

Head-dresses: The crown of feathers, The Atef crown, Great Royal Wife of the Pharaoh with Vultures Crown.

Source:

- Le costume, les armes, les bijoux, la céramique, les ustensiles, outils, objets mobiliers, etc.: chez les peuples anciens et modernes by Friedrich Hottenroth. Paris: A. Guérinet, 1896.

- History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

- Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations by Mary Galway Houston and Florence S. Hornblower. London: A. & C. Black, 1920.

- Art in the house: historical, critical, and aesthetical studies on the decoration and furnishing of the dwelling by Falke, Jacob.