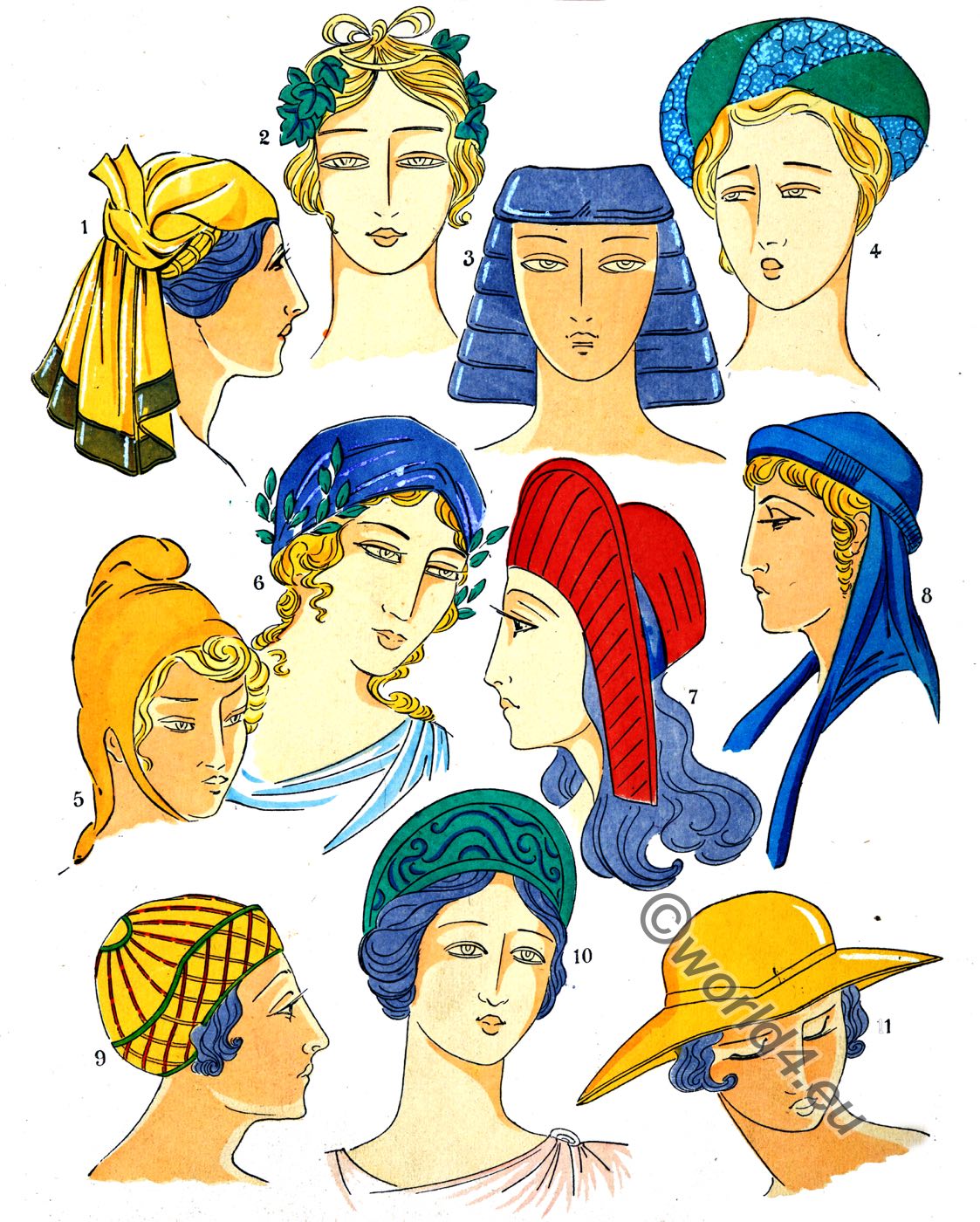

1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

6, 8, 9, 11,

7, 10,

13,

12, 14, 15,

17, 18,

19, 20, 21, 22,

The colour of the dresses. The headgear, Wigs, Hairstyles, Make-up. The care of the hair. Transparent garments.

The ancient Egyptians.

Egypt. Costumes of the high antiquity.

The headgear of the ancient Egyptians consisted of a close-fitting cap, which reached exactly as far as the hair fell backwards to protect the throat and neck from the sun. Since this cap is usually painted yellow on the monuments, one can assume that it was made of leather. The caps are either monochrome or with coloured stripes. A cutout usually left the ears free.

The Nos. 1. 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 21 show different forms of this cap. Some are still attached with ribbons to the forehead and chin, over others golden tiaras are still set. Around those of the kings the Uraeus serpent (Naja haje, Egyptian cobra, symbol for the goddess Wadjet), the divine symbol of the right over life and death, wraps itself.

A wig seems to be attached to No. 15, the use of which in Egypt, especially by distinguished persons, was a general one. Even poor people wore them made of wool. The British and Berlin museums still have originals of such wigs. The latter has two and a half feet of long hair (one English foot = 30.48 cm).

At no. 20 the cap ends in a long tail, under which the artfully plaited and thread-wrapped hair is visible. The Egyptians, men and women alike took great care in the care of their hair. They divided it either into a multitude of spirally twisted curls, or into extremely fine braids (No. 17), or into braids that were arranged very densely one on top of the other, or finally into strong braids (Nos. 10, 12) that were braided with the help of false hair and other means.

No. 19, where the hair growth or the wig is reminiscent of the allonge wigs of the 17th century, is cut exactly the same way as the protective caps at nos. 4 and 5. No. 22 shows the example of a bird-like headdress, which was copied from the sparrowhawk of the guinea fowl, among others.

The Egyptians anointed their whole body. The ladies made abundant use of make-up. They dyed their pupils black and green to make their eyes appear larger. Then they drew a black circle around the eyes with a needle of ivory or ebony, painted the cheeks with red and white, traced the veins on the forehead with blue paint, dyed the lips with carmine and the fingernails with henna, which is still used for the same purpose in the Orient.

The colour of the dresses, which were mostly made of flax or cotton, was usually white, then also monochromatic and colourfully striped like the headgear. Later, namely in Thebes under the Ramesses (19th and 20th dynasty, ca. 1292 B.C. to ca. 1070 B.C.), transparent garments were common, which clearly showed all body shapes. The feet were usually undressed; sandals were worn less frequently. Arms and legs were adorned with golden ribbons, which were richly decorated with precious stones.

No. 7 depicts a mandora player from a Theban tomb of the 18th dynasty. She is wearing one of those transparent robes which were often fastened under the chest and held on the shoulders by straps. Her hair is decorated with a lotus flower.

No. 10 is Ramesses II from the 19th dynasty with the Uraeus serpent after a Theban mural. Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 are bas-reliefs taken from the rock tombs of el-Kab. The subsequent coloration has been tried with the help of other monuments, as well as with the following numbers. Nos. 6 and 12 come from Esneh (Isna), nos. 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22 from the island of Philae, nos. 19 and 20 from Thebes, nos. 7 and 10 are borrowed from the Histoire de l’art egyptien by Prisse d’Avennes (Paris 1863). All other figures are taken from the publications of the French Commission for Egypt.

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.