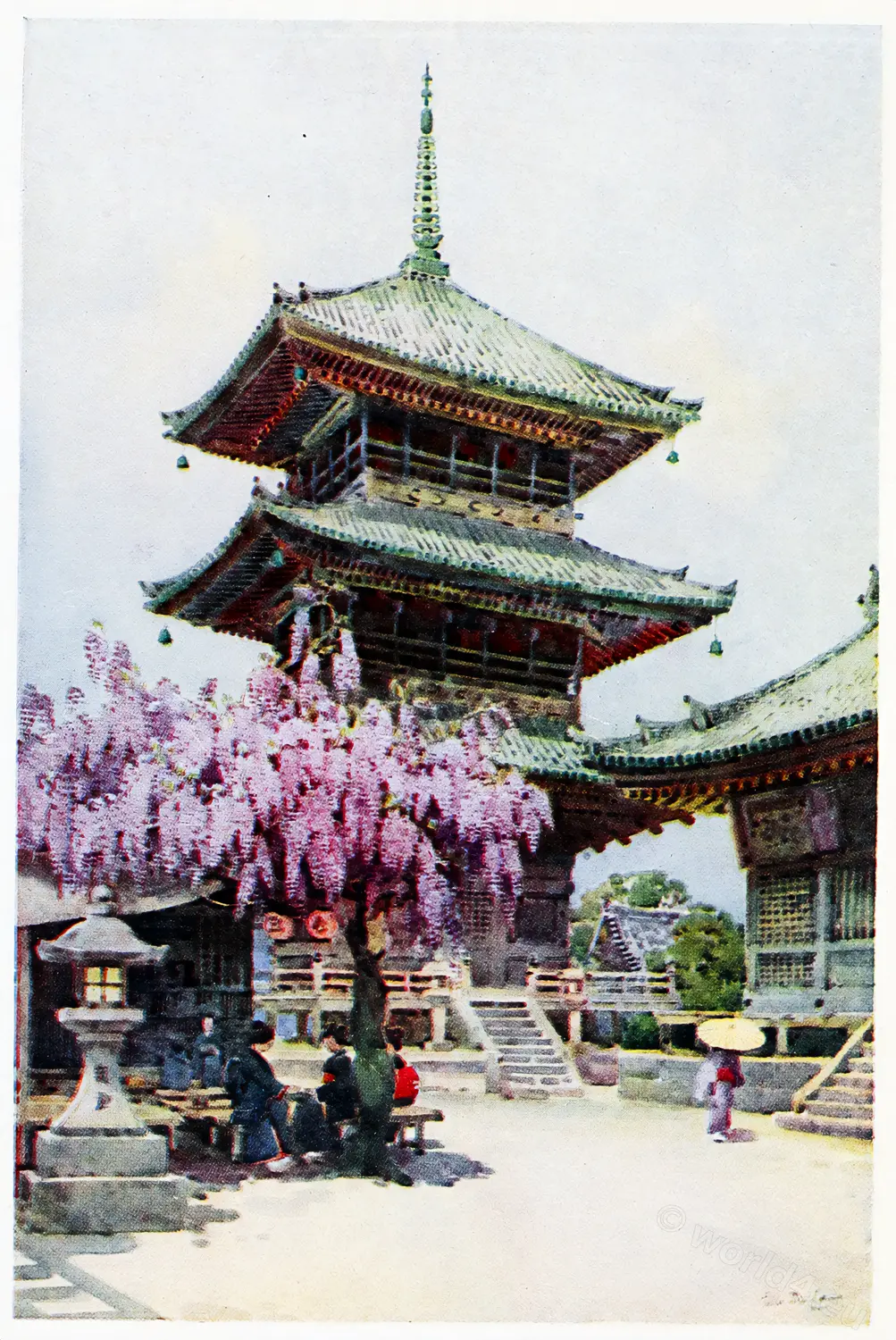

Kaga Province (加賀国 Kaga no kuni) was a former province located in the southern part of today’s Ishikawa prefecture on the island of Honshū. It was sometimes called Kashū (加州).

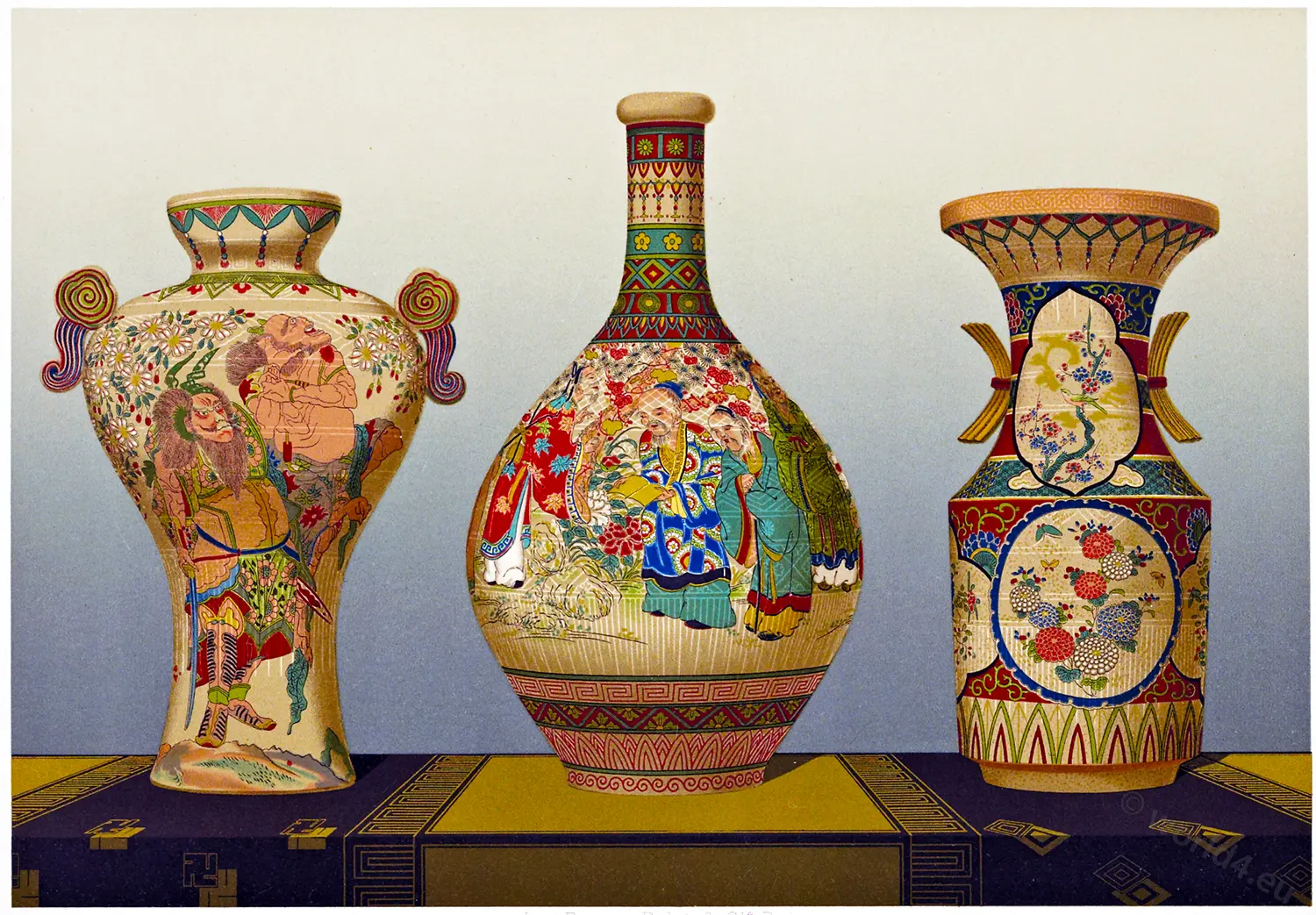

All pottery made in Kaga is known in Japan as Kutani ware. The kilns at KUTANI in Kaga were established in 1664 and made two distinct classes of ware. One of these is called “Ao Kutani,” also Saikō-Kutani (Revival Kutani), or green Kutani, from the predominance of green in the colouring, and is characterised by the use of transparent green, yellow, manganese-violet, and blue enamels of great intensity, washed over strong floral or landscape designs drawn in heavy black outline.

This type is perfectly exemplified by a fine dish in the series at South Kensington brought together by the Japanese Government in 1876. While it appears to be reminiscent in its methods of the “three colour” class of the Chinese, its artistic character is free from extraneous elements and entirely Japanese in genius.

The other type, known par excellence as “Ko Kutani,” or old Kutani (古九谷) ware, includes a brilliant red among its colours, and is the ancestor of the red and gold Kaga porcelain of recent times.

KAGA CERAMIC

by James Lord Bowes.

IF the fascinating faience of Satsuma be excepted, there are none of the ceramic wares of Japan more entitled to our admiration than those produced at the Kutani factories, especially those which have been made since the revival of the industry in the earlier years of the 19th century.

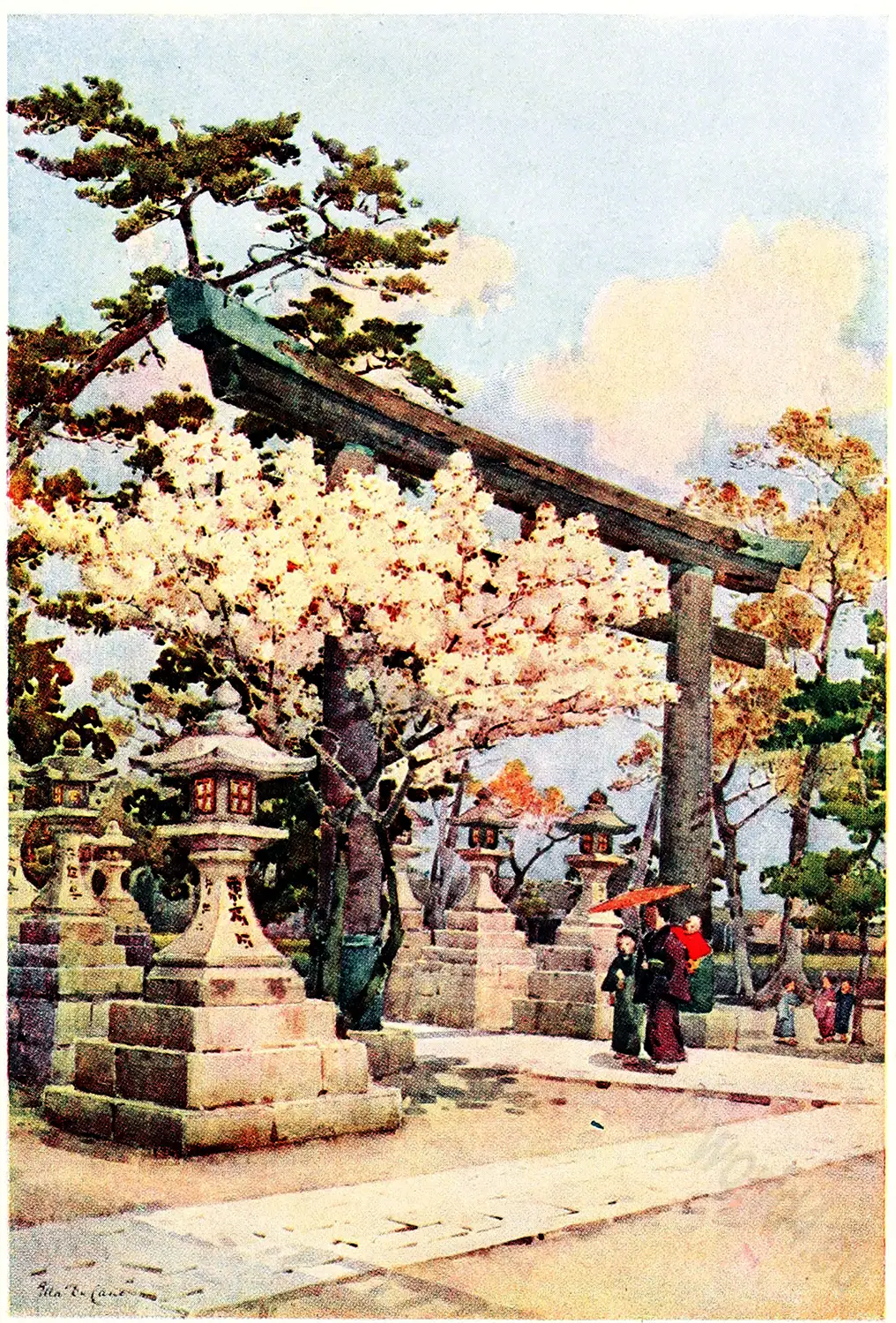

The village of Kutani, or as, perhaps, we should say, the group of villages, for the word Ku-tani signifies Nine valleys, is situated in Kaga, one of the richest and most important of all the provinces of Japan.

We have no information as to the industry having been practised here in the earlier ages. The first we hear of it is that Mayeda Toshiharu, the Prince of Kaga, founded a factory in the period of Kwanei, 1624-1643 a.d., the management of which he entrusted to Tamora Gonzayemon the prince himself, however, appears to have; taken a personal interest in the art, as the princes of that day were wont to do, and it is related in the records of the time that he joined his potter in examining the clay which it was proposed to employ.

The wares made at this early date were in the shape of chaire and other vessels for chanoyu after the style of those produced in Seto, which, since the time of Toshiro, had set the fashion for such objects. Some of these wares may be still in existence but none have come under our notice, and it is probable that they would differ little in either form or glaze from those after which they were

modelled.

Toshiaki, the son of Toshiharu, influenced no doubt by the artistic movement then in progress in the country, sent Goto Saijiro, one of his vassals, to Hizen to acquire a knowledge of the art of making and decorating porcelain, an art for which that province had already become celebrated.

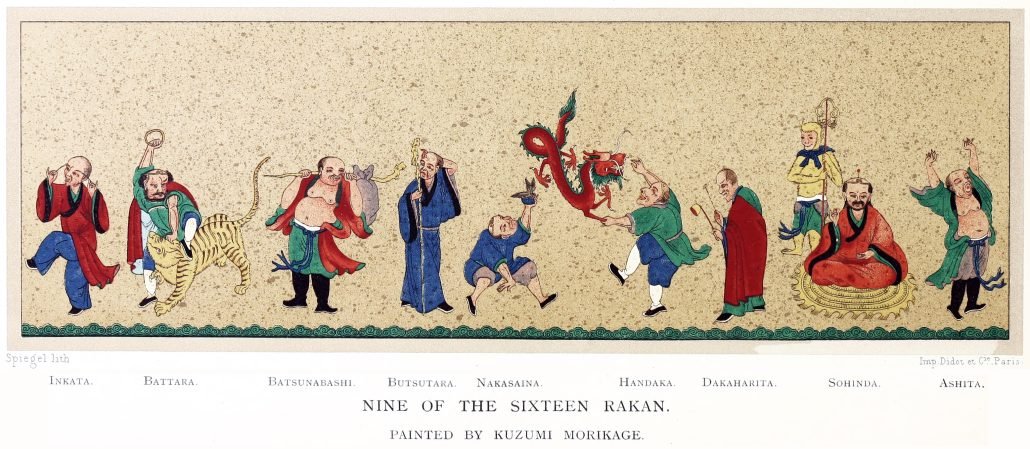

Saijiro returned to Kaga about 1660, and at the same time a well known artist of the Kano school of painting, Kuzumi Morikage, a pupil of Tanniu, came from Tokio, probably upon the invitation of Prince Toshiaki.

The enlarged knowledge of Saijiro enabled him to select clay of a suitable nature for the new industry he proposed to commence; he found it at Muranoshita, in the neighbourhood of Kutani, and in a valley not far off he discovered the necessary colouring matter for the decoration which he had in view.

Examples of Saijiro’s works are most rare; one specimen only, obtained for the collector by Mr. Hayashi, has come before us it is a cliawan of porcelain, not so pure; as that which Hizen potters were then making, but still porcelain of fair quality, which marked a great advance upon the stonewares previously produced. The interior of the bowl is decorated, upon the white glaze, in gold and silver and purple enamel with ho-ho and sprays of botan drawn in an archaic fashion.

But the principal interest of this piece is found in the treatment of the exterior, which is wholly covered with the rich and mottled red colour which has since become the distinguishing feature of the most valued of Kutani wares. Later on we will revert to this, but now we must refer to the works of Morikage which have come into our possession, and which are equally valuable with the specimen of Saijiro’s work in affording a starting point from which to judge and classify the works of this province.

It has already been said that Morikage was a Kano artist, and, therefore, it may be assumed that his drawings would show the Chinese influence which dominated that school of painters; and this is seen in the important bowl in the catalogue. It was originally considered to be of Chinese workmanship, both as regards the object itself and the decoration; but, subsequently, many Japanese connoisseurs have identified the painting as being from the brush of Morikage, and the ware, a semi-porcelain, the work of Gonzayemon.

The decoration, executed upon a ground enamelled in imitation of granite, consists of a Chinese landscape in the interior, and upon the exterior, the figures of nine of the Sixteen Rakan, painted in green, red, blue, black, and purple, of the hues employed by Chinese artists of the Ming dynasty.

These pieces, and a group of similar wares in the ornamentation of which the principal colour is a deep green, with yellow, purple, black and blue enamel, serve to illustrate the earliest works of this factory, which are known as Ko or Ao Kutani, that is, as old or dark green Kutani.

Another example of Morikage’s painting is included in the collection; it, like the specimen already described, is decorated with a landscape, and it may be mentioned that his works are known in Japan as Morikage Shitaye, or Sketches by Morikage.

For how long a time wares of this class were made is not known; probably not for long, for we are told that the art first declined and afterwards ceased, and nothing more is heard of it until the period of Bunkwa when, in 1810, Yoshitaya Denyemon, a merchant in Daijoji, opened a new factory at Kutani which he entrusted to a potter named Miyamotoya Riyemon; four years later this kiln was removed to the town of Yamashiro, a few miles distant, the necessary clay being carried from the hills at Kutani.

With the foundation of this kiln we enter upon the period when the Kaga wares with which we are all now familiar were produced. These wares are of two kinds, those with red grounds after the fashion invented by Saijiro, and those painted in various colours after the manner of Morikage, which we have come to call the polychromatic ware; and there is a third style in which these methods are combined.

Putting aside the early works by Saijiro, Morikage, and the artists who followed their lead, which are now so rare as to be unknown to most collectors, and are so distinctive in their character as to be easily identified by those who are acquainted with the subject, we may at once say that it is an error to suppose that the beautiful Kaga wares which are now so highly appreciated are ancient; none of them is of an earlier date than 1810, when Yoshitaya founded his kiln, and the best examples were made during the half century which succeeded that event.

Gold was used in the decoration of Kaga pottery as early as 1660, for we find it employed by Saijiro upon the bowl previously referred to, and it is used upon one of the works by Morikage which is catalogued, but in both cases it forms part of the internal decoration of the wares and is not applied upon the red grounds with which it is associated in the later and more typical works of the Kutani artists.

Perhaps its free use, as we now see it employed, upon red grounds was originated at Yoshitaya’s factory, by an artist named Iidaya Hachiroyemon, who, after studying the Tokifu, a Chinese work on pottery, introduced this style which has now become teh most characteristic decoration of Kaga ware. It came at once into general favour, and the wares so decorated were known as Hachiro-ye-kinrande or decoration in the style of gold brocade by Hachiro.

The marks which are found upon examples afford us little assistance in identifying the objects made at this early period for they very seldom give the name of the artist or potter, the only mark being that of Kutani, which is in nearly every instance found upon the best and oldest examples alone or sometimes in conjunction with the character Fuku, signifying prosperity or happiness, and this absence of the maker’s names accords with the custom which obtained in the factories which were under the patronage of the princes, as there is little doubt was the case with those of Kaga up to a comparatively recent date.

The reds employed upon the earlier wares referred to are of rather a cold hard tint, and gold is not so freely used as it is on more modern works. Later on we find the reds assume a fuller tone, sometimes approaching a ruddy brown, and having a dappled or mottled effect which forms a very satisfactory ground for the decoration in gold which was then applied more freely than upon the earlier specimens; the makers also commenced to sign their names, in addition to that of the factory, or more properly speaking the ware, for all pottery made in Kaga is known in Japan as Kutani ware.

Specimens of the various periods, arranged according to their dates so far as our information and the advice of Japanese connoisseurs have enabled the collector to accomplish this, are described in the section of the catalogue which deals with the red and gold wares, and these most probably include examples from the earliest years of the present century to the present day.

Amongst them are several pieces which the last Shogun sent to Paris in 1867, one of which is illustrated by chromo-lithography in the frontispiece of this work, and these are probably examples of the earliest productions of Hachiro; there are also a number of works by the Tozan family, which are singularly beautiful both in ware and decoration; and there are specimens of the painting of Sosentei Ichigo, works of Yeiraku, the Kioto potter, who was invited to join the kiln in 1858, down to the more recent wares made for export.

The decoration of this Kutani ware shows a strong Chinese feeling as might be expected when we consider that Hachiro, and also his successors, drew their inspiration from the Tokifu.

This is seen in the representation of Chinese children engaged in play, or of philosophers engaged in study, subjects which fill medallions disposed upon the grounds of red and gold; we also find the Kara-shishi and the ho-ho, both drawn in Chinese style. And of subjects common to both countries are the Seven Gods of Fortune, and many floral compositions.

The three-clawed imperial dragon of Japan indicates the nationality of the artist, and the tai and koi, the fish so beloved of the Japanese, show where the work was done.

Two other features in the decoration are peculiar to the Kutani school—the minute and delicately drawn spiral and dotted pattern which forms the ground work of much of the decoration, and the leaf-work border around the stands of bowls and dishes which is so generally found in this ware.

The second great division of the Kutani pottery made during the 19th century is that which we have called polychromatic ware. It is after the style of Ao Kutani, and the same colours are employed in its decoration, the dark green, purple, black, red and blue enamel, with brown, white and gold as well the tones of these colours are, however, deeper and richer, and the enamels are frequently laid on in greater body than was the case in the original works, producing details in relief which contrast in a highly effective manner with the flat painting in which portions of the subjects are rendered.

This description refers almost entirely to the earliest examples of the ware which were made shortly after the kiln of Yoshitaya was established, to which period the two dishes which come first in the catalogue of this section belong.

The third style to which reference has been made is that in which the methods of the two schools are combined in the decoration of a single object. Several beautiful specimens of this treatment are catalogued with the polychromatic wares, amongst them works signed by Tozan, Kiuroku, Kachoken, and Sosentei, as well as others which bear only the name of the ware or of the province, and these objects, whether regarded as examples of either school, are worthy of the greatest praise and mark the highest development of decorative skill in both.

There is, perhaps, greater variety in the clays used in Kutani wares than in those employed in any other single province. As already remarked, the bowl by Saijiro is almost a pure porcelain, and the objects by Morikage are of a fine close-grained clay, somewhat approaching porcelain in its character; the early Hachiro ware is of similar clay, whilst the first works in polychrome are of a stoneware character. Then we come upon objects in clay of a chalky nature, which give the glaze the soft and warm tone so agreeable to the eye and touch which is one of the characteristics

of the ware; and, later still, we find pure porcelain used, especially in the most modern objects.

Perhaps Saijiro, when he returned from Hizen, brought with him enough porcelain earth for his work, whilst Gonzayemon, when he made the wares for Morikage to paint upon, may have used the clay from the hills of Kutani, which afterwards afforded Yoshitaya the material for his factory, for we know that he drew his supplies from this source, and the earlier Hachiro works are of very similar material to those of Gonzayemon.

The clay of the stoneware character, used at the same time, would no doubt be the ordinary clay of the country of which the chanoyu utensils had been made at the original kiln. The softer and whiter clay and porcelain sand probably came from other provinces, for we find it stated in the native records that not clay alone, but objects of pottery for decoration, were from time to time imported into the province.

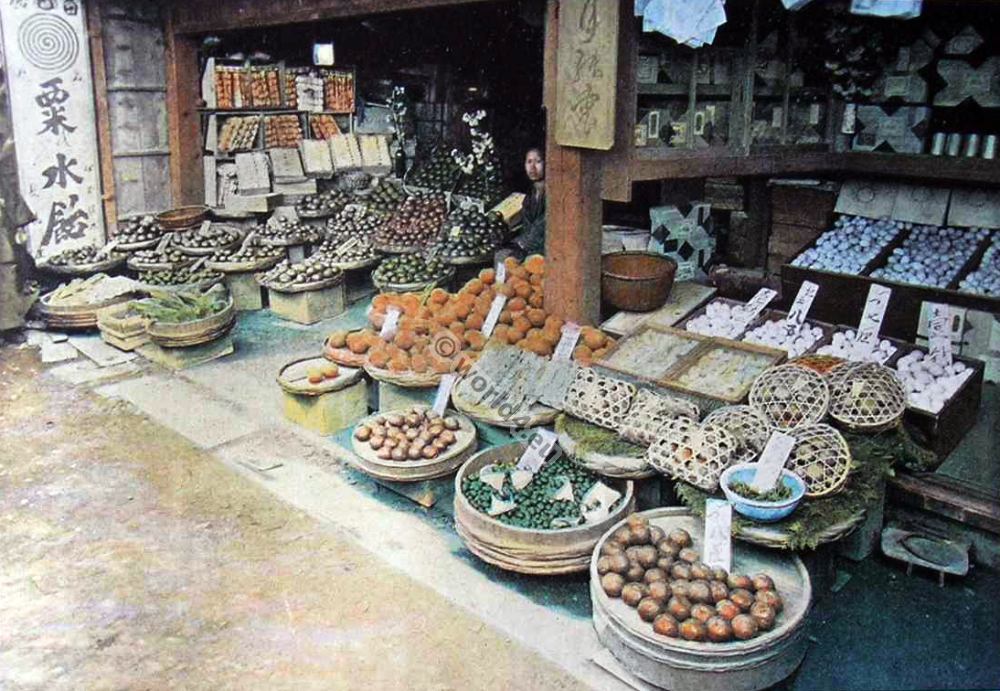

The works of the Kutani potters, before the export trade began, were chiefly in the shape of bowls and dishes, with some flower vases also, and they were generally thick and heavy, for the clay was of a refractory nature and difficult to work, but as regards their form, they were by no means inelegant or rude.

Of the wares made for foreign markets little need be said, for they are to be seen in every town; they are chiefly of the softer clay, or of porcelain, and are in the form of dishes, plates, tea and dinner services, and flower vases; the favourite subject for the decoration of the latter is numerous ancient saints, after the fashion referred to in our remarks about the spurious Satsuma; and the other objects are decorated with floral or figure subjects, in vivid colours upon bright red grounds, ornamented with highly burnished gold, altogether lacking in the tender softness of the early wares.

The principal makers of these goods, of which some specimens are catalogued, are Seikan, Yuzan, Tinzan, Setsuzando, Kisaki, and the descendants of Tozan and Kachoken who produced such worthy work.

I am indebted to Mr. Takamatsu *) for information about the various enamels used in the Kutani factories.

*) On Japanese Pigments. By T. Takamatsu, Tokio; published by the Department of Science in Tokio, Daigaku, 1878.

The most important and distinctive of all is the red enamel, of which the chief constituent is Bengara. The origin of this name has not been ascertained; by some it is thought to have been derived from Bengal, whilst others say that it is the residue of safflower, hence the name, Beni-gara, as it is sometimes written; but this derivation is probably incorrect, because analysis shows that it is red oxide of iron, containing more or less of silica, alumina, etc. It is this oxide, in combination with powdered glass, white lead and silica, that produces the red enamel for which Kutani ware is so deservedly famed.

Mr. Takamatsu gives the composition of this enamel as follows: bengara, 10 parts; shiratama, i.e,, powdered white glass, the soft or lead variety, 25 parts; tonotsuchi, i.e., white lead, to give fusibility to the enamel, 5 parts; hinookaseki, i.e., silica, to decrease fusibility, 6 parts.

Green enamel is composed of rokusho, i.e., carbonate of copper, 4 parts; shiratama, 10 parts; and tonotsuchi, 10 parts.

Yellow enamel of bengara, 0’6; shiratama, 10 parts, and tonotsuchi, 7 parts.

Scarlet enamel of finely powdered gold leaves, 0’5; shiratama, 10 parts; tonotsuchi, 5 parts, and hinookaseki, 10 parts.

Faint purple enamel of kawaragosu, 2 parts; shiratama, 10 parts, and tonotsuchi, 7 parts.

Deep purple enamel is obtained by mixing a certain proportion of konjo, i.e., carbonate of copper or smalt, it is not clear which, with the preceding composition.

For the black enamel, a paste of binoxide of manganese in water is first applied to the glazed surface, which after being dried, is subsequently coated with a mixture of shiratama and tonotsuchi.

The blue’s used in painting Kutani wares are of two kinds; that for colouring the suyaki, or biscuit, is either smalt, or Chinese gosu, a paler blue; the former is too deep a blue for the Japanese taste, whilst the latter is of too faint a shade to please them, so they mix them in order to obtain the colour they desire.

In the first place, they take one part of smalt and mix with nine parts of tonotsuchi, to which a sufficient quantity of gosu is added to give the required tint with this composition, mixed with water, designs are painted upon the biscuit, which is afterwards glazed.

The blue enamel used for painting above the glaze is made of two parts of konjo^ mixed with 5°2 of tonotsuchi, and 3°6 of shiratama.

In preparing the gold for decorating upon the enamelled grounds, the best leaves are selected and powdered in a mortar at intervals for four days, a little water being added from time to time.

Another tint, less bright than that of the pure gold, called awasekin, is obtained by mixing one part of gold leaf with O°1 of borax.

The designs are painted upon the enamel grounds, and the ware is again baked afterwards; the gold is burnished by a piece of steel or agate until the full effect is produced.

There is another factory in this province, situated at Ohi, where a kiln was established in 1681 by Choyemon, a younger brother of Ichiniu, one of the Chojiro family of Kioto. He made objects for the use of chajin of a reddish clay, with a glaze known as ame, which is of a yellowish red colour similar to a jelly made from wheat flour; they do not appear to have possessed any artistic merit and may perhaps be dismissed along with many of the rude wares made for use in chanoyu or for domestic use. Various common wares are still produced at this kiln.

Source:

- Japanese pottery, with notes describing the thoughts and subjects employed in its decoration, and illustrations from examples in the Bowes collection by James Lord Bowes (1834-1899). Liverpool, E. Howell, 1890.

- A book of porcelain: fine examples in the Victoria & Albert Museum, by Bernard Rackham (1876-1964); Victoria and Albert Museum. London: A. & C. Black 1910.

- Oriental ceramic art: illustrated by examples from the collection of W. T. Walters, by Stephen Wootton Bushell (1844-1908). L. Prang & Co., lithographer; D. Appleton and Company, publisher, 1897.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.