The Japanese tea ceremony (jap.茶道 sadō, also called chadō, Engl. roughly tea way; also 茶の湯, cha-no-yu, hot water for tea), also known as the tea ritual, is close to Zen in its underlying philosophy. The tea used is so-called matcha, finely ground green tea. In order to offer the guest the opportunity for inner contemplation, the meeting takes place in a deliberately simply furnished tea house.

THE TEA CEREMONIAL

Content: The Châ-no-you – Its antiquity – Traditions – The ritual character of the ceremony — The Cha-Kai and its subtleties.

CHÂ-NO-YOU.—There is perhaps no custom in the life of the Japanese which manifests his passionate attachment to his traditions more clearly than this, for there is none in which the ancient rites and the lengthy ceremonial are in sharper contrast to that positivism and activity he has learnt from the European.

The tea ceremonial is of great antiquity, if we are to believe that certain priests of the sect of Zen approved it as a salutary means of keeping themselves awake during their midnight services, and that the Abbot Eisai drew up the rules at the beginning of the thirteenth century, to divert the Shôgun Sanetomo (Minamoto) from the temptations of wine. This initial religious phase was succeeded towards the middle of the fourteenth century by a phase of social entertainments of great magnificence.

These were given by the Daimios in their palaces, amidst the gems of their collections and the perfume of the most delicate incense. After a meal of curious refinement, the guest took part in a sort of drawing-room game, being invited by the master of the house to name the special kind of tea which had been served to him.

A correct answer ensured the immediate gift of one of the marvellous objects which surrounded him; but this he was not supposed to take away, for all these beautiful things were destined for the band of geishas who had lent the charm of their talents to the little fete.

The rules of the ceremony were definitely fixed in the following century by Yoshimasa, when, resigning the Shôgunate, he retired to his delightful palace temple of Ginka-Kuji at Kyoto, in company of his two favourites, the abbots Shuko and Shinno. The latter was a highly cultured connoisseur, who invented a certain teaspoon, which all great lovers of tea were bound to manufacture for themselves from a fine bamboo stalk.

Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the custom became a positive mania; the gift of a; china bowl was the highest mark of favour that an inferior could receive from his superior; in any catastrophe, the utensils of the tea ceremonial were saved before anything else; and tales are told of nobles who, when their castles were taken by assault, died with a bowl of tea in their hands. Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, the terrible warriors, were tea-fanatics.

In the autumn of 1587 Hideyoshi issued a veritable edict, enjoining all the tea amateurs in the Empire to gather under the pines of Kitano, near Kyoto, bringing all the objects to be used in the ceremony, which lasted ten days, in the course of which Hideyoshi came to drink with nobles and peasants alike.

Shortly afterwards, in 1594, Hideyoshi summoned to his castle of Fushimi the heads of the principal schools of tea in the kingdom; one of these was Senno Rikyu, the first to collate, purify, and modify the rules of the tea ceremonial, and to give them that character of simplicity and severity which they have retained ever since. The doctrine, the imperious discipline, and the rigorous etiquette to which all participants must still adhere are the very personal work of Rikyu; but he failed to observe a like strictness in his moral conduct, and later, Hideyoshi, weary of his venality and peculation, one day sent him the order to kill himself.

All Japanese houses, save those of the lowest class, contain the characteristic little room called the tchâ-séki, specially reserved for the tea ceremonial.

It is very small, just large enough to contain the six persons who participate in it, but it is panelled with the most precious and highly finished woods in the house; like all the other rooms, it has a little tokonoma for the kakemono and the vase with a flower or a branch of foliage, a kind of alcove with a sliding door, through which the servants come and go, and a ceiling which follows the slope of the roof to the exterior wall.

On this side, which adjoins the garden, there is a little casement on a level with the floor, a veritable cat-hole, through which one has to enter on all fours, if I may so express myself.

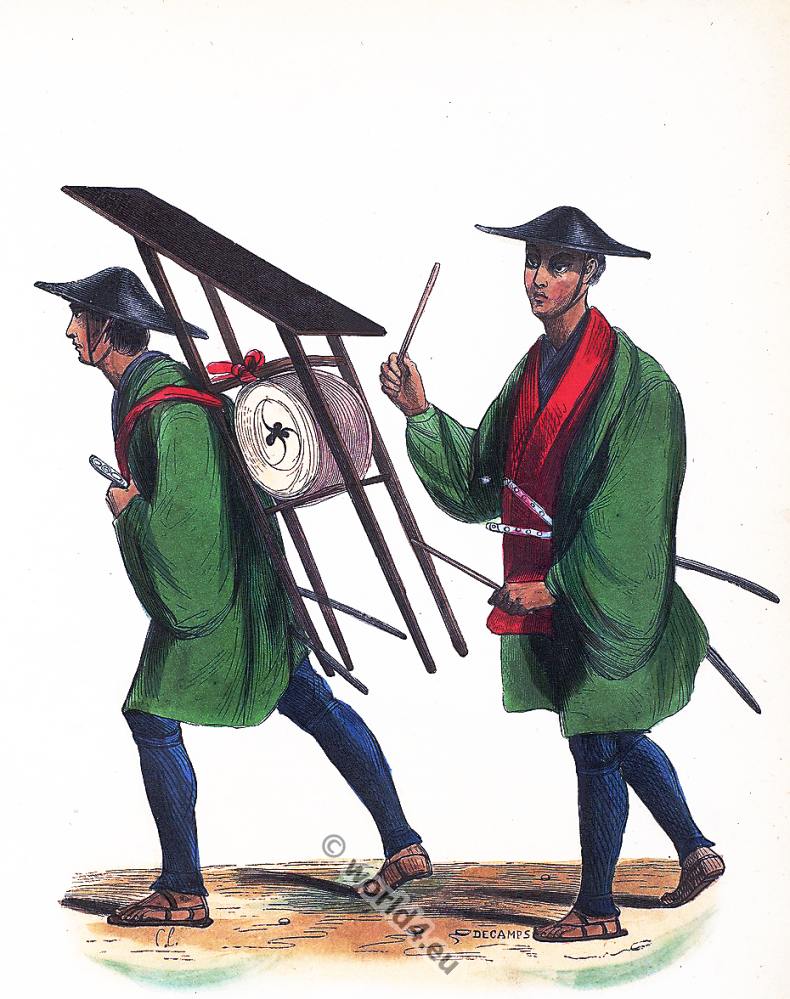

Yet it is only by this opening that you are permitted to enter the tchâ-séki after the master has taken you to walk in his garden, stepping from one flat stone to another in straw sandals, and sitting for a few moments under a little rustic shelter over a bench commanding the prettiest view, which is always of very limited extent in a respectable Japanese garden.

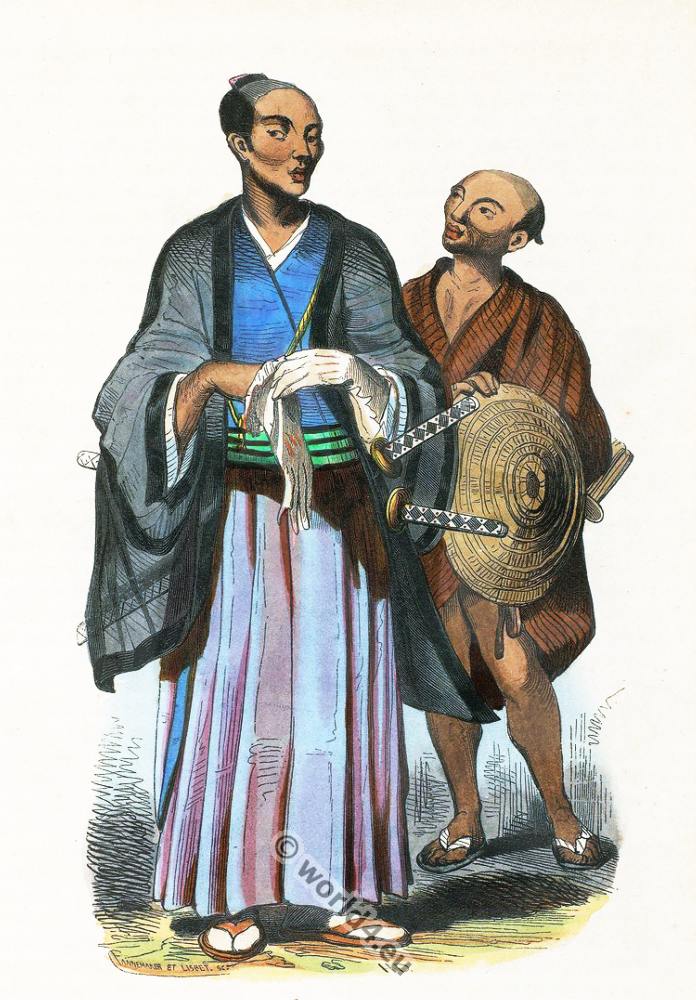

One by one the five guests take off their sandals, and slip through the aperture into the tchâ-séki. They take their places, sitting on their heels, on a silken cushion, the guest who is to be specially honoured nearest the tokonoma. The sliding door opens, and the master of the house appears; he carries all the utensils to be used in the tea ceremony on a lacquered tray. If the festival is complete, it is preceded by a dinner, which he himself serves to his guests; for it is the rule that no servant shall appear.

He bows with his whole body, kneeling, his forehead almost touching the mats, and the guests are expected to return the greeting by bowing very low in their turn. From this moment an almost unbroken silence must be observed while the rites of the ceremony are in progress; but it is considered polite for the principal guest to make some remark on the beauty of the kakemono (jap. 掛け物 or Kakejiku 掛け軸) in the tokonoma (床の間). *)

*) The tokonoma (literally: bed niche) is an essential element of traditional Japanese architecture. It is a small ground-level or slightly raised niche or bay window about 50 cm deep and 1 to 2 m wide. Tokonoma are usually found in washitsu, traditional Japanese rooms covered with tatami (rice straw mats).

The master uncovers a narrow rectangle cut in the floor, and with a goose-feather he flicks the edges of the lacquered hearth, the cinders of which are dyed with tea. He seizes a few glowing embers in a large brazier of hammered iron by means of two silver sticks, fans them with a branch of bleached spindle-wood, and sprinkles them with a few grains of incense, which at once perfume the room.

He then places on them the metal teapot, which he has filled with water from a splendid mitsusashi of Tamba or Karatsou, using for this purpose a reed ladle with a long bamboo handle.

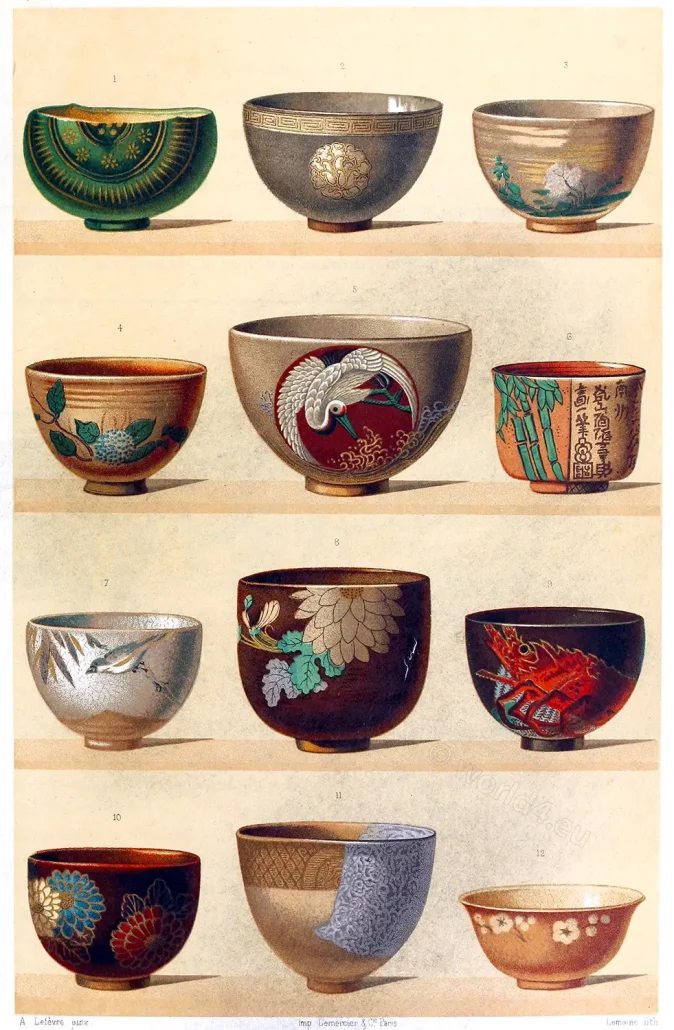

Then with a slight spatula very graceful in form, cut from the knotted stem of the finest brown or speckled bamboo, he takes a few pinches of green tea, which he deposits in a magnificent Corean or Rakouan bowl. This bowl is more or less open in shape according to the season of the year.

He pours into it the boiling water from the teapot, and stirs with a rattan brush, the hairs of which are formed of the supple fibres of the wood. A thick green froth rises on the mixture.

He then presents the bowl, with a low bow, to the principal guest, who responds with a similar bow, and drinks a mouthful, the bitterness of which is terribly harsh to the throat, handing on the bowl to his neighbour.

The thick infusion suffices for the five persons present, each of whom after drinking wipes the edge of the bowl with a piece of soft paper; the last guest finds only a muddy sediment, which he swallows with gusto.

The bowl is then passed back from hand to hand; threads of green moss still cling to the inner surface, making a curious effect on the black or pink enamel ground of the Rakous, or the white-and-grey of the Coreans.

Each person praises the workmanship, smiles at the fanciful designs of the transparent glazes, sometimes solidified into vitreous globules, and tries to guess from which workshop it came — a problem the owner is fond of putting forward.

Finally, the bowl returns to his hands; he rinses and dries it, does the same to all the objects he has just used, puts everything in order, covers up the hearth with its lacquered lid, and leaves the room after another ceremonious bow to his guests.

The service — for such it is — is over, with its consecrated rites, its array of formal rules by which every act, every gesture, has been prescribed once for all. The guests go out backwards by the loophole through which they entered, and join the master, who has preceded them into the garden.

Cha-kai. — Literally translated: “A gathering on the pretext of tea-drinking.” Certain amateurs in a town combine to get up little gatherings of this sort in their houses on certain days. The invitations are sent out, and the guests may, if they choose, go from one house to the other.

In each a servant distributes tea and haricot cakes in one of the rooms; on entering, the guest prostrates himself, the forehead almost touching the ground, the palms of the hands laid upon it.

The company crouches on the mats, kneeling, the heels supporting the weight of the body, which is slightly thrown backward. The pale tea is poured into little cups without handles; its harsh, bitter flavour is not softened by sugar.

It is permissible not to eat the sugared sponge-cake handed with it; but in this case it is de rigueur to wrap it in a piece of the fine paper made of vegetable fibre, of which every Japanese carries a packet, and to take it away with you.

Every amateur who is on friendly terms with the host makes a point of contributing to the decoration of the house, and guests are invited primarily to admire all the things thus brought together.

The walls are hung with boudjin kakemonos that is to say, works of a literary character, in which both eyes and intelligence are to find pleasure.

They generally date from the end of the eighteenth century or the first half of the nineteenth, and are painted according to the Chinese tradition. They represent landscapes with sharp mountain peaks, piled one behind the other in perspective, with torrents rushing into deep ravines; in the majority there is no suggestion of a direct impression from Nature, but a dry formula totally devoid of feeling. Western taste will never be able to understand the high prices with which collectors at sales will outbid each other to secure the famous works of Chikuden or Bousson.

Large trays are set out, on which splendid prints are piled with a rare knowledge of values, kakis, peaches, and crimson apples. They look as if they had been prepared to be painted in some still-life by a Gauguin. In old baskets with a sombre patina, in vases of sandstone or of bronze, a spray of flowers or a branch loaded with fruit is arranged with infinite art.

Numerous schools, frequented by women and young girls, teach nothing but this art, which is based on the most ancient traditions.

What subtle taste there was in the combination of a branch of worm-eaten wood splashed with moss, and another branch bearing on its extremity a scarlet pomegranate half open and ready to fall, the two grouped in a fine celadon vase.

In others, the sanquirai reared its stems, studded with yellow and red berries; mozouren spread its horizontal twigs, bearing little leaves and long split pods, displaying tightly packed scarlet fruits. The aqueto which bears a flower like the crest of a cock, unfolded its large golden or crimson leaves like flowers, their tips still green before the brilliant hues of decay had invaded them.

In little jardinières of decorated china stood dwarf shrubs, maples or pines, trained by the cunning orthopædy of the garden, spreading out their twisted branches, and showing all the dignity and fine proportions of secular trees.

Exquisite things stand about on little lacquered tables with inverted legs, stoneware from Corea, bronzes, lacquers. The visitors take them up, look at them, criticise them.

Gently and caressingly, with pious, reverent hands, an old Châ-jin with gold spectacles and a black silk skull-cap, took up a jade kogo of pale amethyst colour, the lid of which had been carved in a yellowish vein of the jade, and examined it carefully. All the Religion of Beauty was in his gesture.

Source: In Japan: pilgrimages to the shrines of art by Gaston Migeon (1861-1930). London: W. Heinemann, 1908.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.