Clothing in Ancient Greece.

History and Dress.

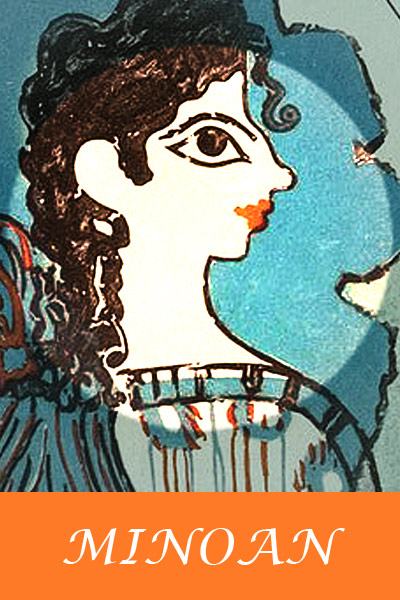

Greek Costume.—(1) Pre-Hellenic otherwise called Minoan or Mycenaean Age (2800-1200 B.C.). Men wore waist cloth with hanging ends. Women wore tight-fitting waists and flounced skirts.

(2) Homeric or Heroic Age (1200 B.C.). Both men and women wore a simplified costume not unlike the classic.

Dorian Invasion, 8th century B.C. Rise of Sparta, inhabitants called Dorians. Rise of Athens, 5th century B.C., inhabitants called Ionians.

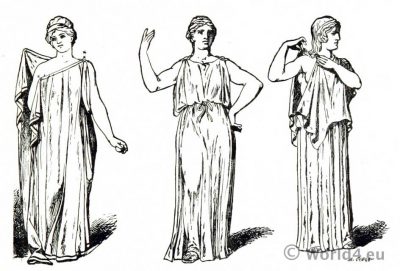

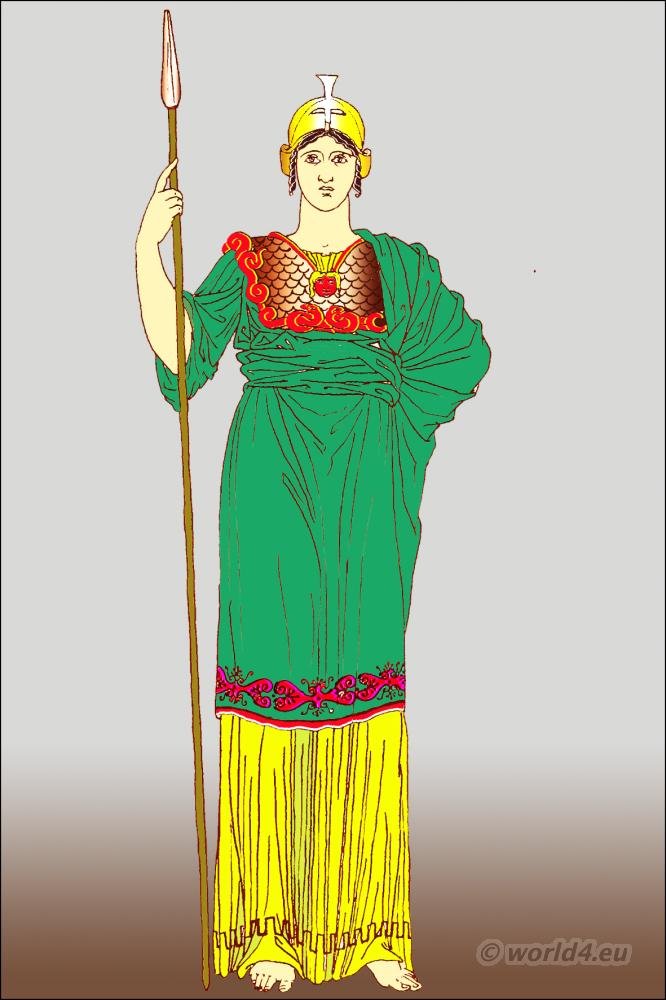

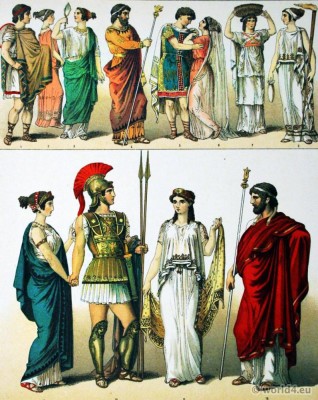

(3) Classic Period. Costume of Greek men and women was the same except that of the men was more abbreviated.

(a) Chiton or dress.

(b) Himation or cloak.

(c) The chlamys or short coat was worn on horseback. The chiton or dress was of two kinds. The Doric chiton, worn by the Dorians, who were warlike and interested primarily in the physical, made of heavy material and fell in few folds, had no sleeves.

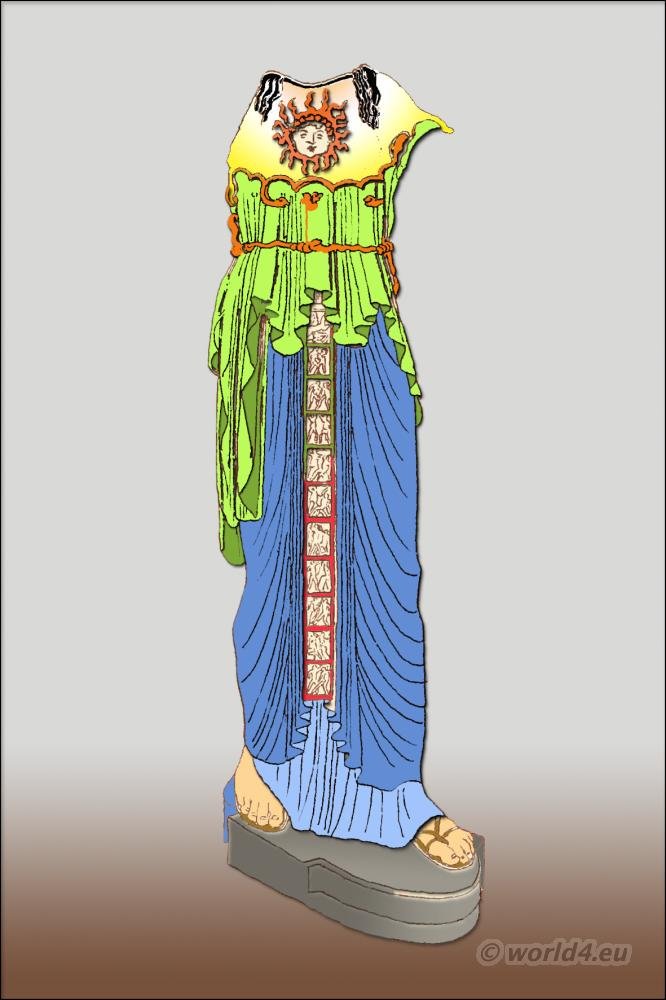

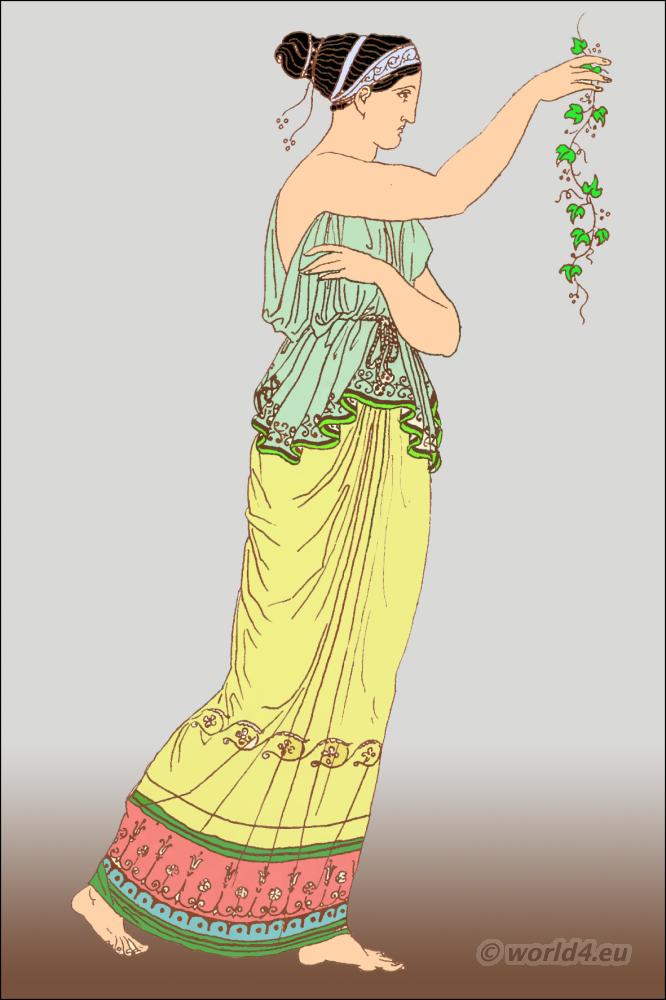

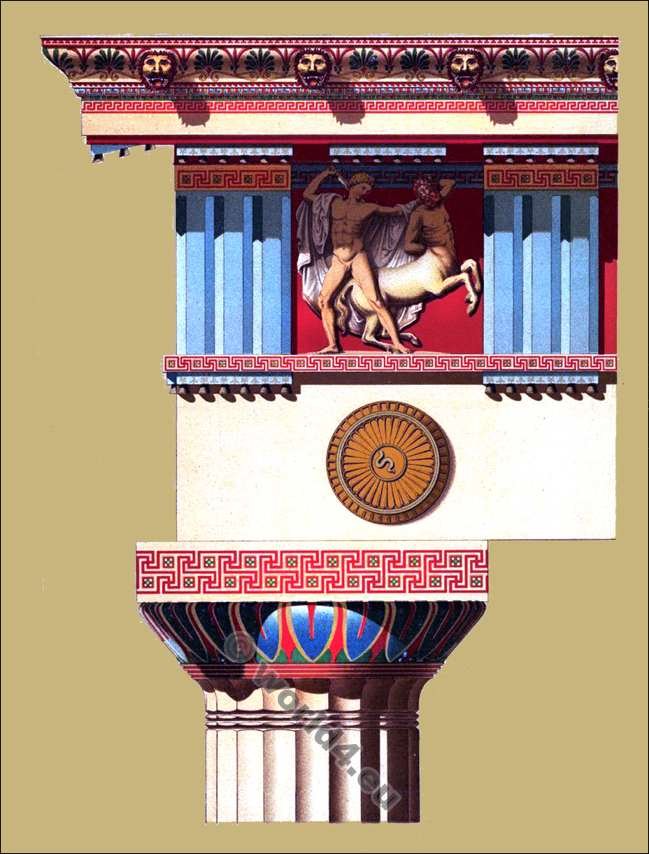

The Ionic chiton, worn by the Ionians, a people fond of all things beautiful, made of finer material, fell in many and finer folds, had sleeves. Girdle was worn at the waistline during the Archaic period, sixth century B.C. Statues of people of this century adorn the Acropolis. This was the elaborate period when cascades of material are found in the statues.

Girdle worn over the hip or below the waist in the Golden Age. This was sometimes called the Age of Pericles, 459-431 B.C. The maidens of the Parthenon frieze are of this time. Girdle worn under the arms during the last period. Wool, linen and silk were used, and the garments were dyed purple, red, yellow, and other colors. Sandals and shoes were worn when out of doors, and the women had many different kinds of jewelry and hair ornaments.

Auguste Racinet. The Costume History by Françoise Tétart-Vittu.

Racinet’s Costume History is an invaluable reference for students, designers, artists, illustrators, and historians; and a rich source of inspiration for anyone with an interest in clothing and style. Originally published in France between 1876 and 1888, Auguste Racinet’s Le Costume historique was in its day the most wide-ranging and incisive study of clothing ever attempted.

Covering the world history of costume, dress, and style from antiquity through to the end of the 19th century, the six volume work remains completely unique in its scope and detail. “Some books just scream out to be bought; this is one of them.” ― Vogue.com

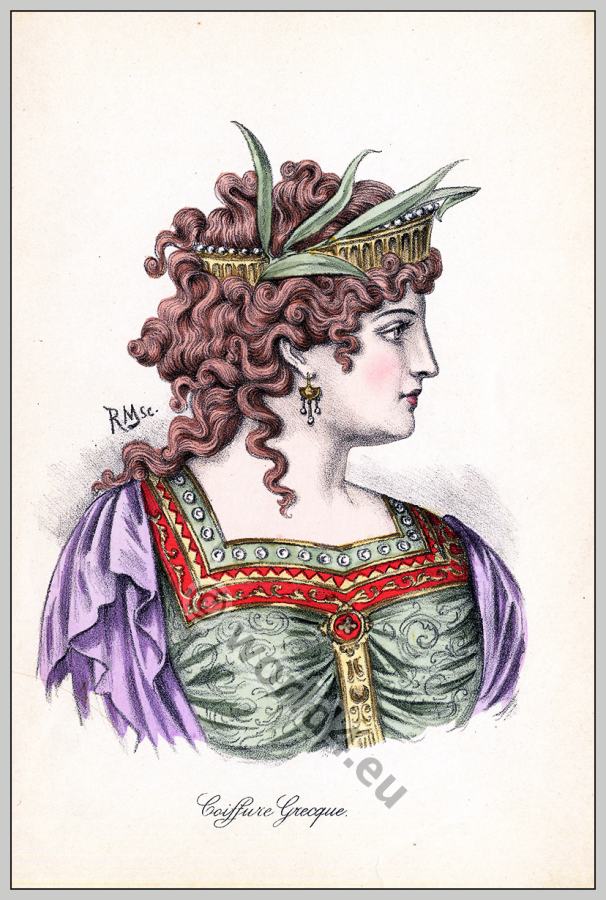

Greek Hair, Headdresses.

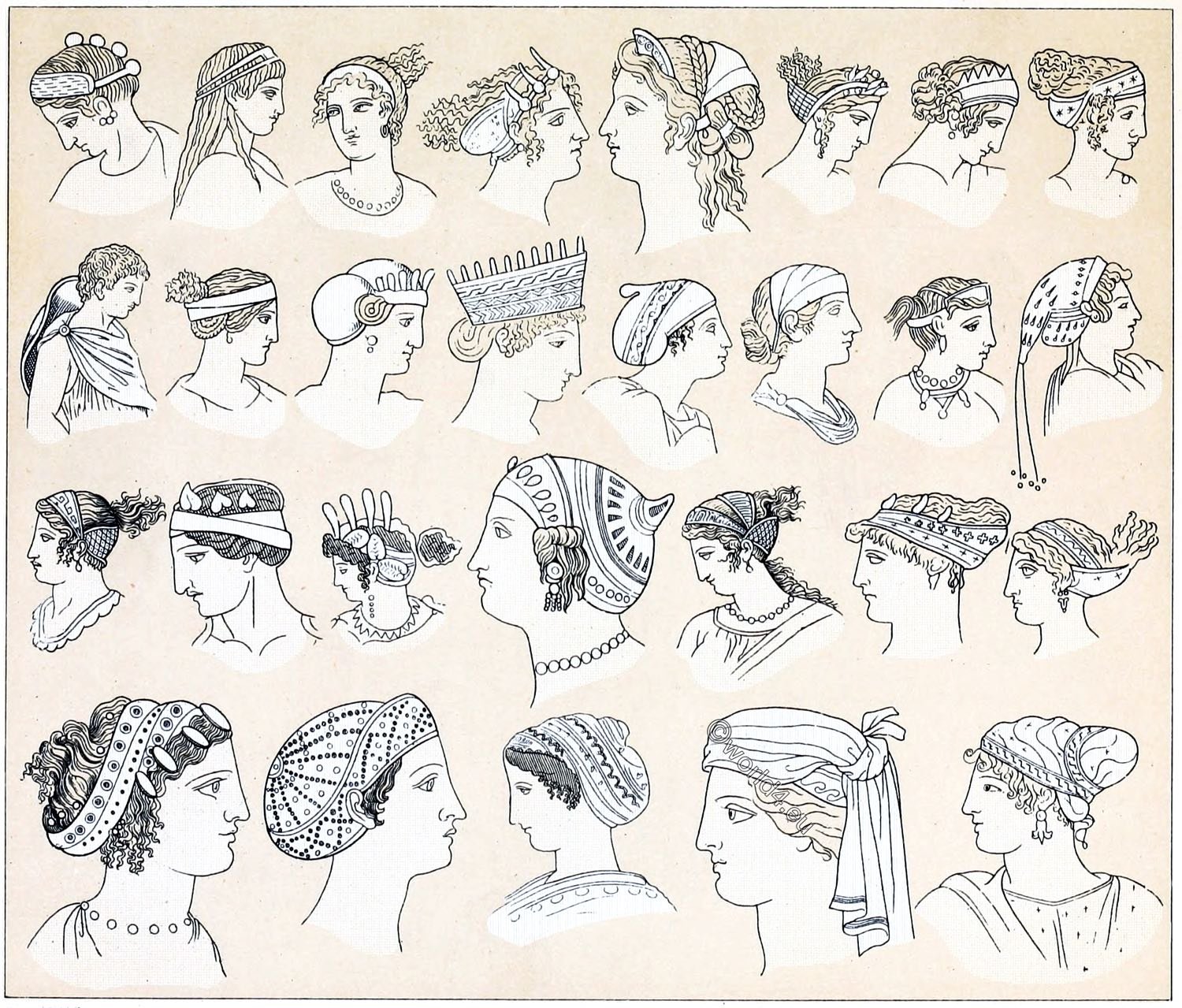

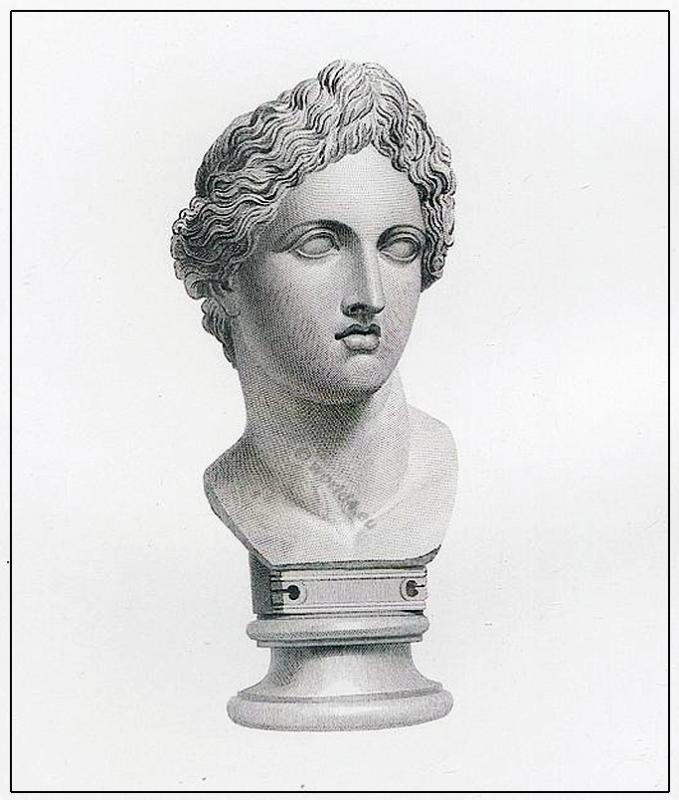

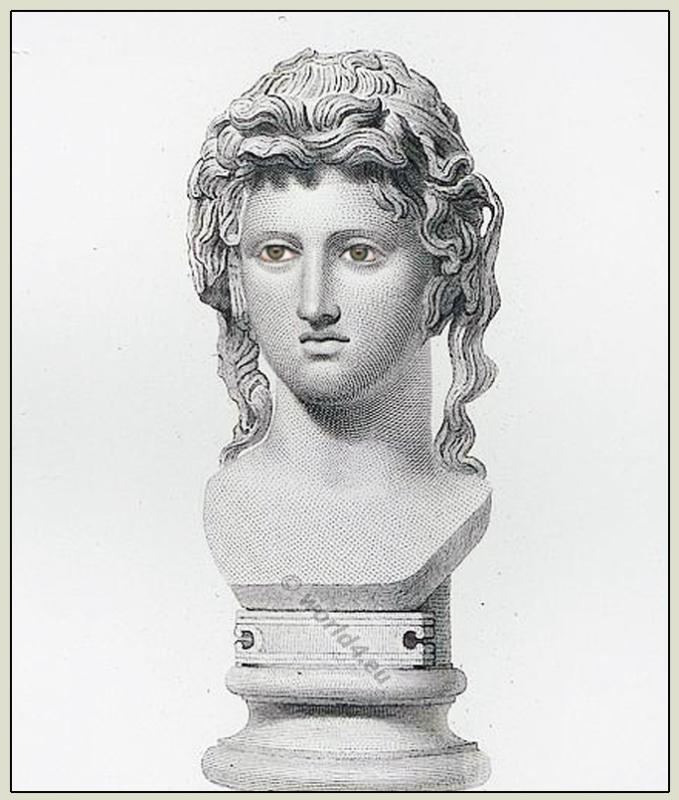

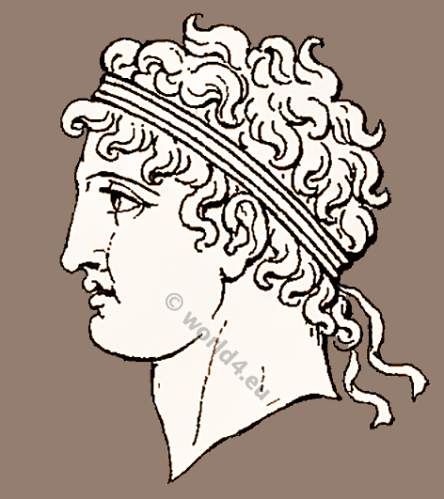

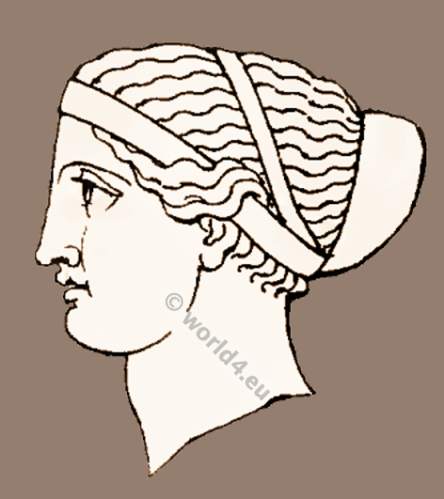

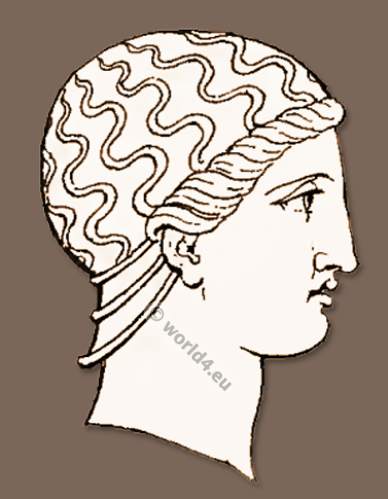

IT is precisely in its earliest periods that the Grecian attire, whether of the head or of the body, exhibits in its arrangement the greatest degree of study, and if I may so call it, of foppishness.

In those Grecian basso-relieves and statues which either really are of very early workmanship, or which at least profess to imitate the style of work of the early ages (formerly mistaken for Etruscan), every lock of hair is divided into symmetrical curls or ringlets, and every fold of the garment into parallel plaits; and not only the internal evidence of those monuments themselves, but the concurring testimony of authors, shows that in those remote ages heated irons were employed both to curl the hair and beard, and to plait the drapery.

It was only in later times that the covering, as well of the head as of the body, was left to assume a more easy and uncontrolled flow.

At first, as appears both from ancient sculpture and paintings, men and women alike wore their hair descending partly before and partly behind in a number of long separate locks, either of a flat and zig-zagged, or of a round and corkscrew shape.

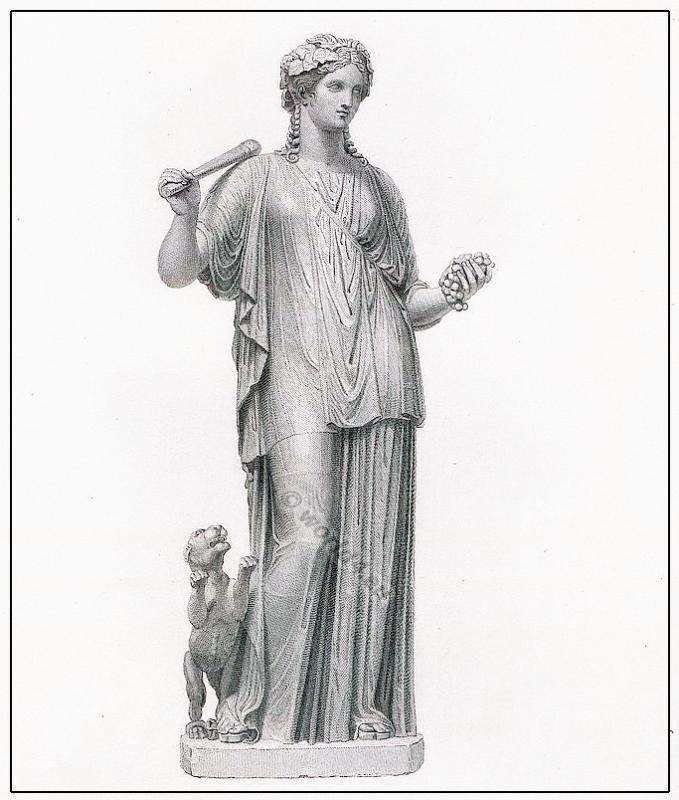

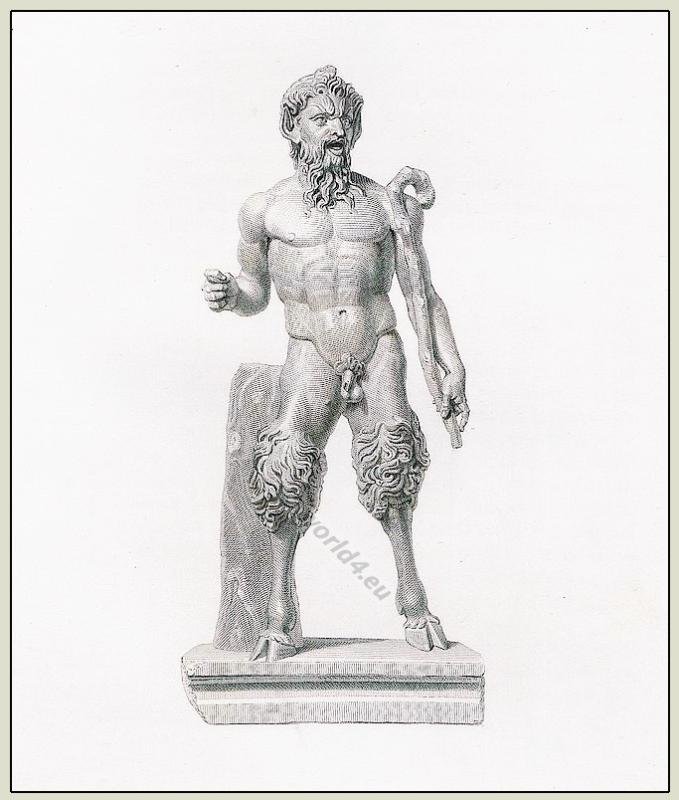

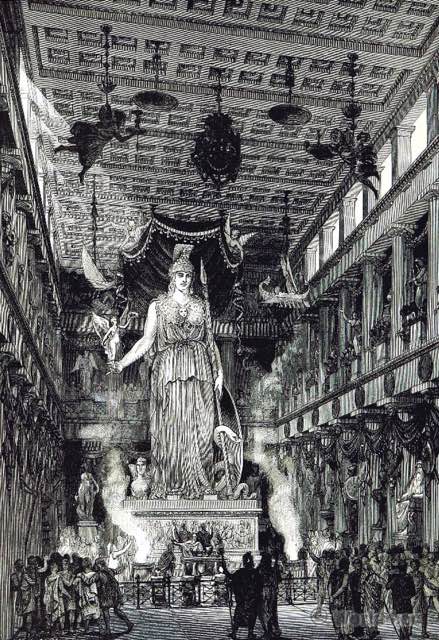

A little later it became the fashion to collect the whole of the hair hanging down the back, by means of a riband, into a single broad bundle, and only to leave in front one, two, or three long narrow locks or tresses hanging down separately; and this queue was an ornament which Minerva, a maiden affecting old fashions and formality, never seems to have quitted; and which Bacchus, though not originally quite so formal, yet when on his return from amongst the philosophers of India he also chose to assume the beard and mien of a sage, thought proper to readopt.

Later still, this queue depending down the back was taken up; and doubled into a club; and the side locks only continued in front, as low down as the nipple. But these also gradually shrunk away into a greater number of smaller tufts or ringlets, hanging about the ears, and leaving the neck quite unconfined and bare. So neatly was the hair arranged in both sexes round the forehead, and in the males round the chin, as sometimes to resemble the cells of a beehive, or the meshes of wire-work.

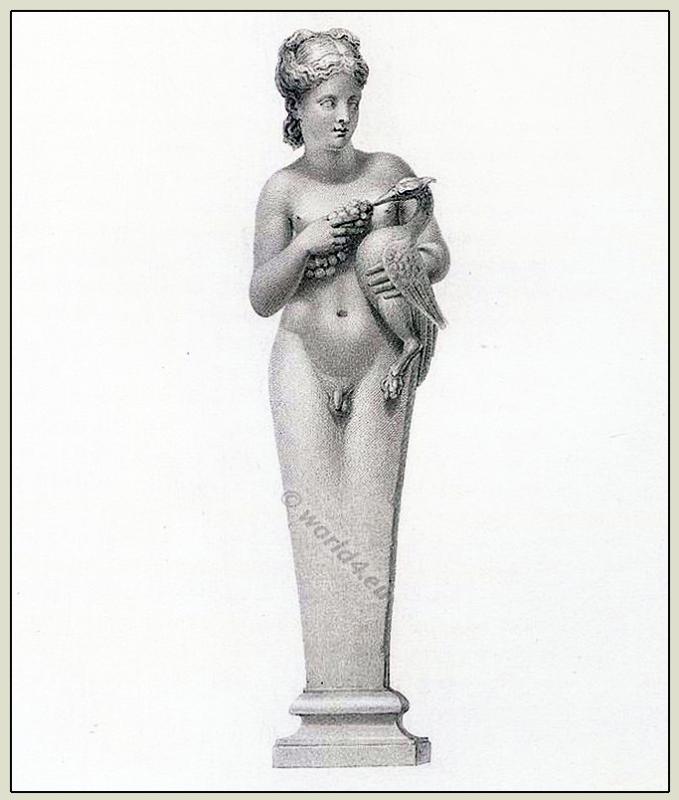

With regard to the attire of the body, the innermost article,- that garment which does not indeed appear always to have been worn, but which, whenever worn, was always next the skin,- seems to have been of a light creasy stuff, similar to the gauzes of which to this day the eastern nations make their shirts.

The peculiar texture of this stuff not admitting of broad folds or drapery, this under garment was in early times cut into shapes fitting the body and arms very closely, and joined round the neck, and down the sleeves, by substantial hems or stays of some stouter tissue. But even this part of the attire seems in later times to have been worn very wide and loose round the body, and often at the shoulders; where, as in the figures of Minerva and of the bearded Bacchus, the sleeves are gathered up in such a way as totally to lose their shape.

The outer garment assumes in the figures of the old style an infinite variety of shapes, but seems always to have been studiously plaited; so as to form a number of flat and parallel folds across its surface, a zig-zag line along its edge, and a sharp point at each of its angles.

Though the costume of the Greeks appears to have been more particularly of the sort just described, at the periods when the sieges of Troy and of Thebes were supposed to have taken place, and is in fact represented as such in the more ancient monuments relative to those events, the later works of art, nevertheless, even where they profess to represent personages belonging to those early ages, usually array them in the more unconfined habiliments of more recent times. In the male figures even of such primeval heroes as a Hercules, an Achilles, and a Theseus, we generally find the long formal ringlets of the heroic ages omitted for the short crops of the historic periods.

I shall now enter into a somewhat greater detail with regard to the different pieces of which was composed the Grecian attire.

The Tunic or Chiton

The principal vestment both of men and of women, that which was worn next the skin, and which, consequently, whenever more than one different garment were worn one over the other, was undermost, bore in Greek the name of χίτων; in Latin that of tunica. It was of a light tissue; in earliest times made of wool, in later periods of flax, and last of all, of flax mixed with silk, or even of pure silk. Its body was in general composed of two square pieces sewed together on the sides.

Sometimes it remained sleeveless, only offered openings for the bare arms to pass through, and was confined over the shoulders by means of clasps or buttons; at other times it had very long and wide sleeves; and these were not infrequently, as in the figures of Minerva and of the bearded Bacchus, gathered up under the arm-pits, so as still to leave the arms in a great measure bare.

Most usually however the body of the tunic branched out into a pair of tight sleeves reaching to near the elbow, which in the most, ancient dresses were close, with a broad stiff band running down the seams, and in more modern habiliments open in their whole length, and only confined by means of small buttons carried down tile arms, and placed so near the edge of the stuff as in their intervals to show the skin. In very richly embroidered tunics the sleeves sometimes descended to the wrists; in others they hardly reached half way down the upper arm.

The tunic was worn by females either quite loose, or confined by a girdle: and this girdle was either drawn tight round the waist, or loosely slung round the loins. Often, when the tunic was very long, and would otherwise have entangled the feet, it was drawn over the girdle in such a way as to conceal the latter entirely underneath its folds.

It is not uncommon to see two girdles of different widths worn together, the one very high up, and the other very low down, so as to form between the two in the tunic a puckered interval; but this fashion was only applied to short tunics by Diana, by the wood nymphs, and by other females fond of the chase, the foot race, and such other martial exercises as were incompatible with long petticoats.

Among the male part of the Greek nation, those who, like philosophers, affected great austerity, abstained entirely from wearing the tunic, and contented themselves with throwing over their naked body a simple cloak or mantle; and even those less austere personages who indulged in the luxury of the tunic, wore it shorter than the Asiatic males, or than their own women,and almost always confined by a girdle.

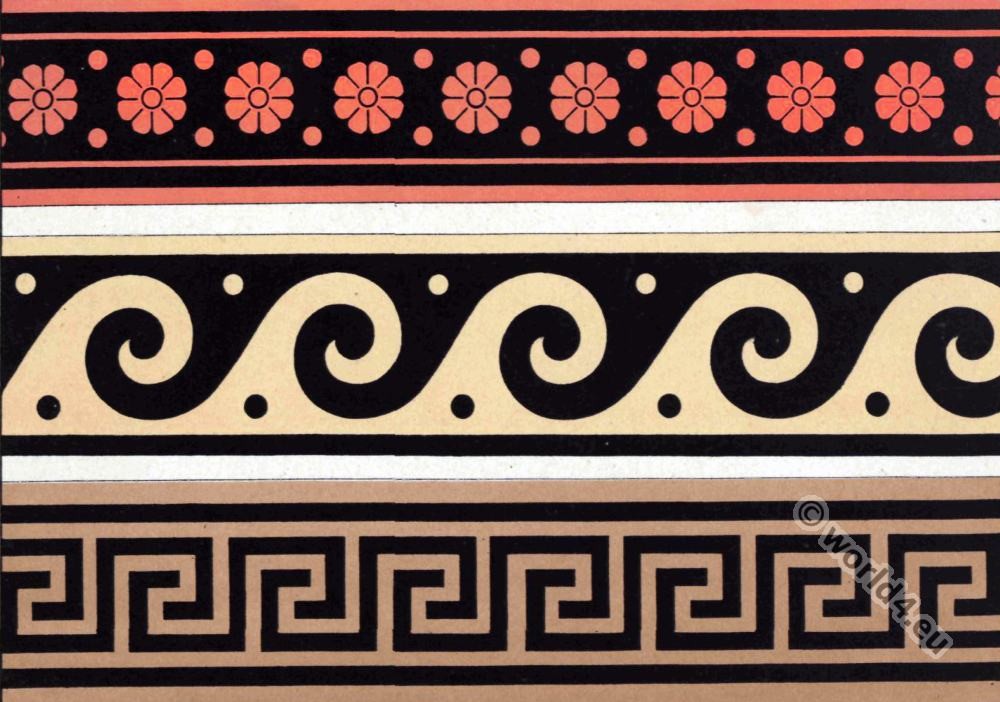

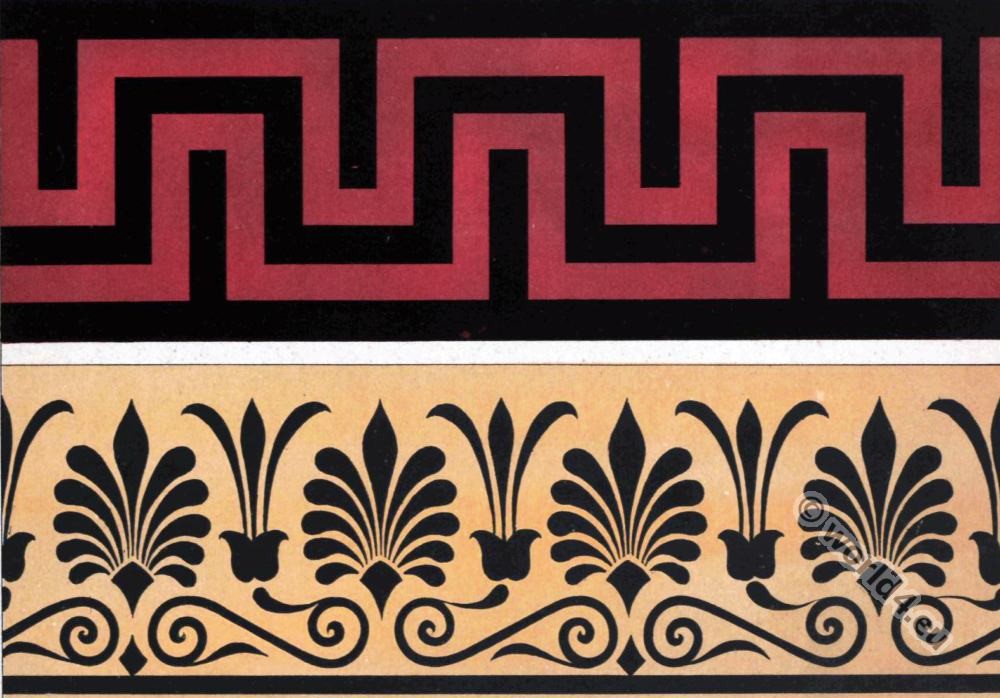

From Greek vases and paintings we learn that the tunic often was adorned with sprigs, spots, stars, &c., worked in the ground of the stuff; and rich scrolls, meanders, &c., carried round its edges; and this tunic was frequently, as well out of doors as within, worn without any other more external garment. In mourning, when the Grecian ladies cut their hair close to the head, they wore the tunic black.

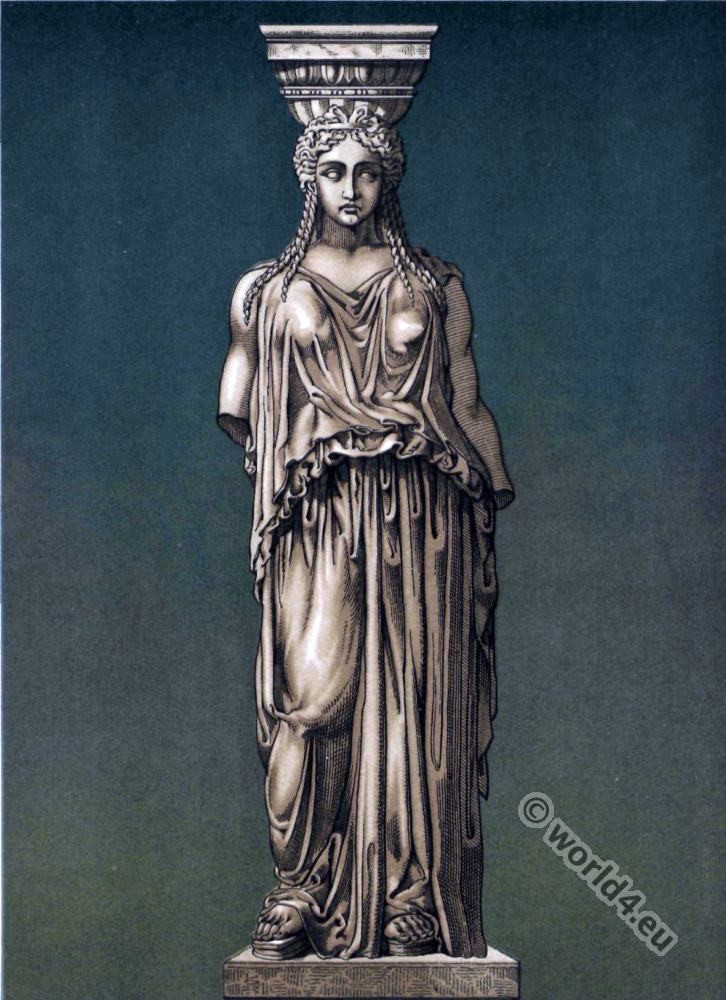

Over this tunic or under garment, which was made to reach the whole length of the body down to the feet, Grecian females generally, though not always, wore a second and more external garment, only intended to afford an additional covering or protection to the upper half of the person.

This species of bib seems to have been composed of a square piece of stuff, in form like our shawls or scarfs, folded double, so as to be apparently reduced to half its original width, and was worn with the doubled part upwards, and the edge or border downwards next the zone or girdle. It was suspended round the chest and back, in such a way that its centre came under the left arm, and its two ends hung down loose under the right arm; and according as the piece was square or oblong, these ends either only reached to the hips, or descended to the ankles. The whole was secured by means of two clasps or buttons, which fastened together the fore and hind part over each shoulder.

In later times this bib, from a square piece of stuff doubled, seems to have become a mere single narrow slip, only hanging down a very short way over the breasts; and allowing the girdle, even when fixed as high as possible, to appear underneath.(1)*

The Peplum.

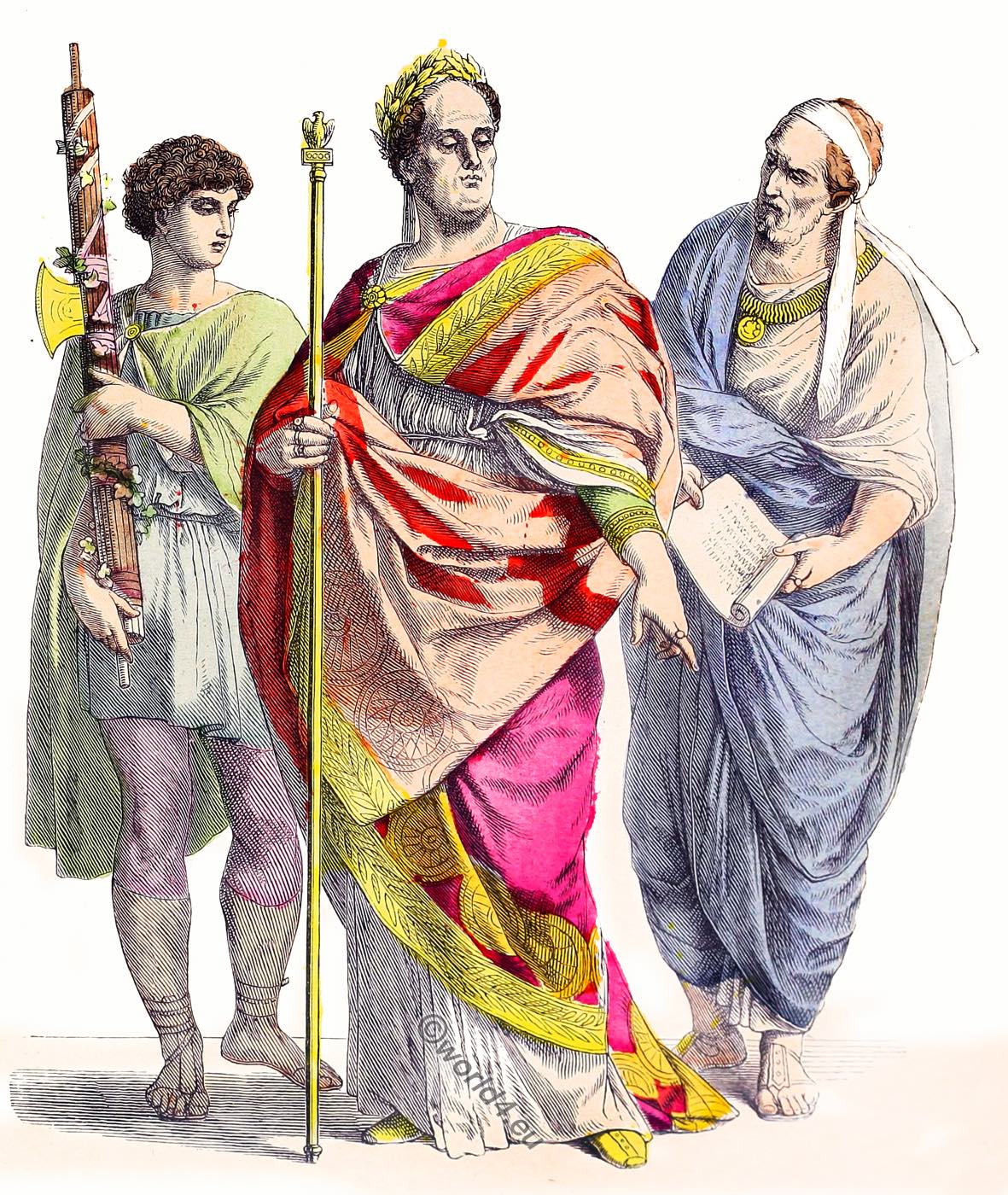

The peplum constituted the outermost covering of the body. Among the Greeks it was worn in common by both sexes, but was chiefly reserved for occasions of ceremony or of public appearance, and as well in its texture as in its shape, seemed to answer to our shawl. When very long and ample, so as to admit of being wound twice round the body-first under the arms, and the second time, over the shoulders-it assumed the name of diplax.

In rainy or cold-weather it was drawn over the head. At other times this peculiar mode of wearing it was expressive of humility or of grief, and was adopted by men and women when in mourning, or when performing sacred rites; on both which accounts it was thus worn by Agamemnon, when going to sacrifice his daughter.

This peplum was never fastened on by means of clasps or buttons, but only prevented from slipping off through the intricacy of its own involutions. Endless were the combinations which these exhibited; and in nothing do we see more ingenuity exerted, or more fancy displayed, than in the various modes of making the peplum form grand and contrasted draperies. Indeed the different degrees of simplicity or of grace observable in the throw. of the peplum, were regarded as indicating the different degrees of rusticity or of refinement inherent in the disposition of the wearer.

For the sake of dignity, all the goddesses of the highest class, Venus excepted, wore the peplum; but for the sake of convenience, Diana generally had hers furled up and drawn tight over the shoulders and round the waist, so as to form a girdle, with the ends hanging clown before or behind. Among the Greeks the peplum never had, as among the barbarians, its whole circumference adorned by a separate fringe, but only its corners loaded with little metal weights or drops, in order to make them hang down more straight and even.

The Chlamys

A veil of lighter tissue than the peplum was often worn by females. It served both as an appendage of rank, and as a sign of modesty. On the first account it is seen covering the diadem of Juno, the mitra of Ceres, and the turreted crown of Cybele, and of the emblematical figures of cities and of provinces; and on the latter account it is made, in ancient representations of nuptials, to conceal the face of the bride. Penelope, when urged to state whether she preferred staying with her father, or following her husband, is represented expressing her preference of the latter, merely by drawing her veil over her blushing features.

Gods and heroes, when traveling, or on some warlike expedition, and men in inferior stations or of simple manners, at all times used instead of the ample peplum to wear a shorter and simpler cloak called chlamys, which was fastened over the shoulder or upon the chest with a clasp. Such is the mantle we observe in the Belvedere Apollo; and in many statues of Mercury, a traveller by profession; as well as in those of heroes and of other simple mortals.

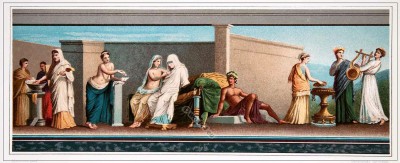

Besides these dresses common among all ranks and stations, the Greeks had certain other vestments appropriate to certain peculiar characters and offices. Apollo, when in the company of the Muses, wore in compliment to the modesty of those learned virgins, a long flowing robe, similar to that of females.

Bacchus, and his followers of both sexes, often appear wrapped up in a faun or tiger (2)* skin; and heralds distinguish themselves by a short stiff jacket, divided in formal partitions, not unlike the coats of arms of the same species of personages in the times of chivalry.

Actors, comic and tragic, as well as other persons engaged in processions sacred or profane, wore fantastical dresses, often represented on vases and other antique monuments.

The Tiara, The Mitra

The numerous colourless Greek statues still in existence, are apt at first sight to impress us with an idea that the Grecian attire was most simple and uniform in its hue; but the Greek vases found buried in tombs, the paintings dug out of Herculaneum and of Pompeya (Pompeii was an ancient Roman city near Naples), and even a few statues in marble and in bronze, enriched with stained or with inlaid borders, incontestably prove that the stuffs were equally gaudy in their colours and varied in their patterns. The richest designs were traced upon them, both in painting and needle-work.

Greatly diversified were, among the Grecian females, the coverings of both extremities. Ladies reckoned among the ornaments of the head the mitra, or bushel-shaped crown peculiarly affected by Ceres; the tiara, or crescent-formed diadem, worn by Juno and by Venus; and ribands, rows of beads, wreaths of flowers, nettings, fillets, skewers, and gewgaws innumerable.

The feet were sometimes left entirely bare. Sometimes they were only protected underneath by a simple sole, tied by means of thongs or strings, disposed in a variety of elegant ways across the instep and around the ankle; and sometimes they were also shielded above by means of shoes or half-boots, laced before, and lined with the fur of animals of the feline tribe, whose muzzle and claws were disposed in front.

Ear-rings in various shapes, necklaces in numerous rows, bracelets in forms of hoops or snakes for the upper and lower arms, and various other trinkets were in great request, and were kept in a species of casket or box, called pyxis, from the name of the wood of which it was originally made; and these caskets, as well as the small oval hand mirrors of metal, (the indispensable insignia of courtesans) the umbrella, the fan formed of leaves or of feathers, the calathus or basket of reeds to hold the work, and all the other utensils and appendages intended to receive, to protect, or to set off whatever appertained to female dress and embellishment, are often represented on tho Grecian fictile vases.

The Petasus

The men, when travelling, protected their heads from the heat or the rain by a flat broad-brimmed hat tied under the chin with strings, by which, when thrown off, it hung suspended on the back. Mercury, and heroes on their journeys, are represented wearing this hat. There was also a conical cap, without a rim, worn chiefly by sea-faring people, and which therefore characterises Ulysses.

The same variety in the covering of the feet was observable among men as among women. Soldiers fastened a coarse sole, by means of a few strings, round the ankle; philosophers wore a plain shoe. Elegant sandals, with straps and thongs cut into various shapes, graced the feet of men of rank and fashion.

The Diadem or Credemnon.

Crowns and wreaths of various forms and materials were much in use among the Greeks. Some of these were peculiarly consecrated to particular deities, as the turreted crown to Cybele, and to the figures emblematic of cities; that of oak leaves to Jupiter, of laurel leaves to Apollo, of ivy or vine branches to Bacchus, of poplar to Hercules, of wheat-ears to Ceres, of gold or myrtle to Venus, of fir twigs to the fauns and sylvans, and of reeds to the river gods. Other wreaths were peculiarly given as rewards to the winners in particular games.

Wild olive was the recompense in the Olympic, laurel in the Pythiac, parsley in the Nemean, and pine twigs in the Isthmic games. Other similar ornaments, again, served to indicate peculiar stations or ceremonies. The diadem or fillet called credemnon, was among gods reserved for Jupiter, Neptune, Apollo, and Bacchus, and among men, regarded as the peculiar mark of royalty.

The radiated crown, formed of long sharp spikes emblematic of the sun, and always made to adorn the head of that deity, was first worn only on the tiaras of the Armenian and Parthian kings, and afterwards became adopted by the Greek sovereigns of Egypt and of Syria. A wreath of olive branches was worn by ordinary men at the birth of a son, and a garland of flowers at weddings and festivals. At these latter, in order that the fragrance of the roses and violets with which the guests were crowned might be more fully enjoyed, the wreath was often worn, not round the head, but round the neck.

As a symbol of their peaceful authority, gods, sovereigns, and heralds, carried the scepter, or hasta, terminated not by the metal point, but by the representation of some animal or flower. As the emblem of their missive and conciliatory capacity, Mercury and all other messengers bore the caduceus twined round with serpents.

The Armor of the Greeks

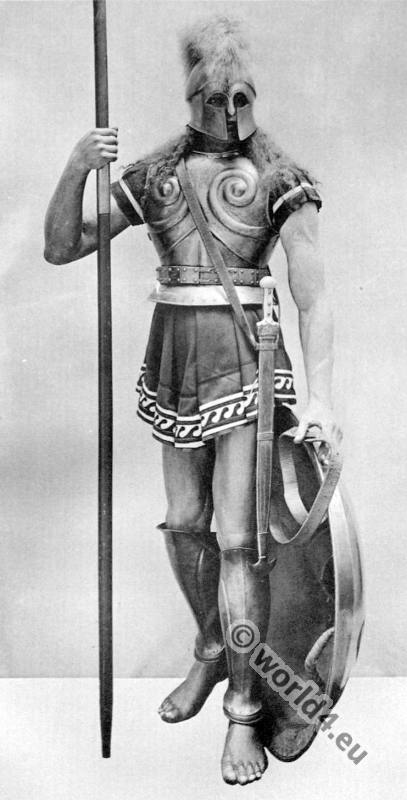

The defensive armor of the Greeks consisted of a helmet, breast-plate, greaves, and shield, of the helmet there were two principal sorts; that with an immovable visor, projecting from it like a species of mask, and that with a movable visor, sliding over it in the shape of a mere slip of metal.

The helmet with the immovable visor, when thrown back so as to uncover the face, necessarily left a great vacuun between its own crown and the skull of the wearer, and generally had, in order to protect the cheeks, two leather flaps, which, when not used, were tucked up inwards.

The helmet with the movable visor usually displayed for the same purpose a pair of concave metal plates, which were suspended from hinges, and when not wanted were turned up outwards. Frequently one or more horses manes cut square at the edges, rose from the back of the helmet, and sometimes two horns or two straight feathers issued from the’ sides, Quadrigræ, sphinxes, griffins, sea-horses, and other insignia, richly embossed, often covered the surface of these helmets.

The body was guarded by a breast-plate or cuirass; which seems sometimes to have been composed of two large pieces only, one for the back and the other for the breast, joined together at the sides; and sometimes to have been formed of a number of smaller pieces, either in the form of long slips or of square plates, apparently fastened by means of studs on a leather doublet.

The shoulders were protected by a separate piece, in the shape of a broad cape, of which the ends or points descended on the chest, and were fastened by means of strings or clasps to the breast-plate.

Generally, in Greek armor this cuirass is cut round at the loins; sometimes, however, it follows the outline of the abdomen, and from it hang down one or more rows of straps of leather or of slips of metal, intended to protect the thighs.

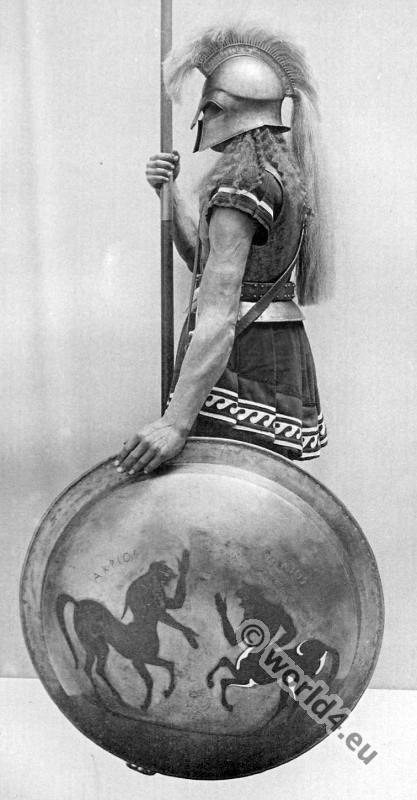

The legs were guarded by means of greaves rising very high above the knees, and probably of a very elastic texture, since, notwithstanding they appear very stiff, their opposite edges approach very near at the back of the calf, where they are retained by means of loops or clasps. Those greaves are frequently omitted, particularly in figures of a later date. The most usual shield was very large and perfectly circular, with a broad flat rim, and the centre very much raised, like a deep dish turned upside down.

The Theban shield, instead of being round, was oval, and had two notches cut in the sides, probably to pass the spear or javelin through. All shields were furnished inside with loops, some intended to encircle the arm, and to be laid hold of by the hand. Emblems and devices were as common on ancient shields “as on the bucklers of the crusaders. Sometimes, on, fictile vases, we observe a species of apron or curtain suspended from the shield, by way of a screen or protection to the legs.

The chief offensive weapon of the Greeks was the sword. It was short and broad, and suspended from a belt on the left side, or in front.(3)* Next in rank came the spear; long, thin, with a point at the nether end, with which to fix it in the ground; and of this species of weapon warriors generally carried a pair.

Hercules, Apollo, Diana, and Cupid, were represented with the bow and arrows. The use of these, however, remained not, in after-times, common among the Greeks, as it did among the Barbarians. Of the quivers some were calculated to contain both bow and arrows, others arrows only. Some were square, some round, Many had a cover to them to protect the arrows from dust and rain, and many appear lined with skins. They were slung across the back or sides by means of a belt passing over the right shoulder.

Independent of the arms for use, there was other armour of lighter and richer texture, wrought solely for processions and trophies; among the helmets belonging to this latter class some had highly finished metal masks attached to them.

The car of almost each Grecian deity was drawn by some peculiar kind of animal; that of Juno by peacocks, of Apollo by griffins, of Diana by stags, of Venus by swans or turtledoves, of Mercury by rams, of Minerva by owls, of Cybele by lions, of Bacchus by panthers, of Nepture by sea-horses.

In early times warriors among the Greeks made great use in battle of cars or chariots drawn by two horses, in which the hero fought standing, while his squire or attendant guided the horses, In after times these bigræ, as well as the quadrigræ drawn by four horses abreast, were chiefly reserved for journeys or chariot races.

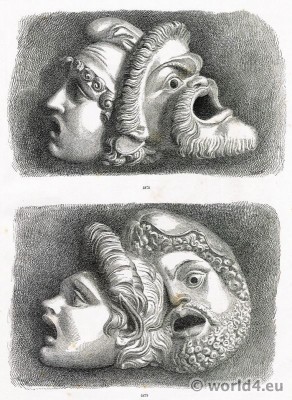

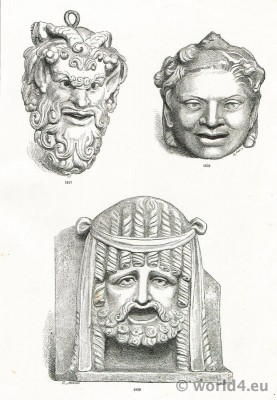

Greeks masks

The Gorgon’s head, with its round chaps, wide mouth and tongue drawn out, emblematic of the full moon, and regarded as an amulet or safeguard against incantations and spells, is for that reason found not only on the formidable ægis of Jupiter and of Minerva, as well as on cinerary urns and in tombs, but on the Greek shields and breast-plates, at the pole-ends of their chariots, and in the most conspicuous parts of every other instrument of defence or protection to the living or the dead.

Of the Greek galleys, or ships of war, the prow was decorated with the cheniscus, frequently formed like the head and neck of an aquatic bird; and the poop with the aplustrum, shaped like a sort of honeysuckle. Two large eyes were generally represented near the prow, as if to enable the vessel, like a fish, to see its way through the waves.

I shall not make this short sketch an antiquarian treatise, by launching into an elaborate description of Grecian festivals. In the religious processions of the Greeks masks were used, as well as on their theatre, in order to represent the attendants of the god who was worshipped.

Thus, in Bacchanalian processions, (the endless subject of ancient bas-reliefs and paintings) the fauns, satyrs, and other monstrous beings, are only human individuals masked; and in initiations and mysteries, the winged genii are in the same predicament: and the deception must have been the greater as the ancient masks were made to cover the whole head.

Of these masks (which together with all else that belonged to the theatre were consecrated to Bacchus) there was an infinite variety. Some representing abstract feelings or characters, such as joy, grief, laughter, dignity, vulgarity, expressed in the various modifications of the comic, tragic, and satyric masks; others offering portraits of real individuals, living or dead.

The thyrsus, so frequently introduced, was only a spear, of which the point was stuck in a pine cone or wound with ivy leaves; afterwards, in order to render less dangerous the blows given with it during the sports of the Bacchanalian festival, it was made of the reed called ferula.

Musical instruments

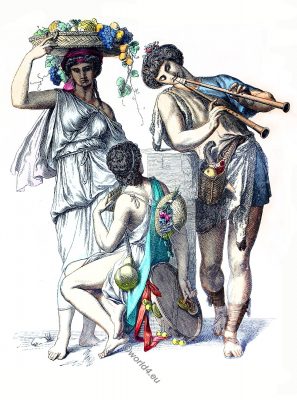

Infinitely varied were the Greek dances; some slow, some quick, some grave, some gay, some voluptuous, some warlike. It was common at feasts to have women that professed dancing and music, called in to entertain the guests.

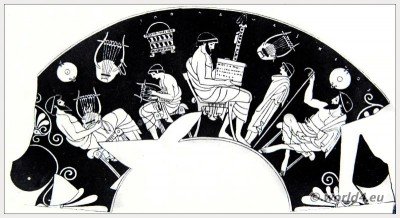

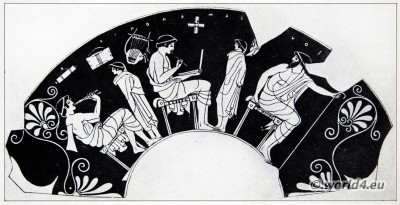

As of musical modes, so of musical instruments there was a great diversity. The phorminx, or large lyre, dedicated to Apollo, and played upon with an ivory instrument, called plectrum, seems, from certain very intricate and minute parts always recurring in its representations, to have been a very complicated structure.

It was usually fastened to a belt slung across the shoulders, and sometimes suspended from the wrist to the left hand, while played upon with the right. The cithara, or smaller lyre, dedicated to Mercury, and, when its body was formed of a tortoise shell and its handles composed of a pair of goat’s horns, more strictly called chelys, was played upon by the fingers.

The barbitos was a much longer instrument, and emitting a graver sound. To these may be added the trigonum, or triangle; an instrument borrowed by the Greeks from Eastern nations, and much resembling the harp.

Independent of these instruments with cords, the Greeks had several wind instruments, principally the double flute, and the syrinx, or Pan’s flute. To these may be added certain instruments for producing mere noise, such as the tympanon, or tambourine, a metal hoop covered with skin adorned with ribands or bells, chiefly used in the festivals of Bacchus and of Cybcle; the crembala, or cymbals, formed of metal cups; and tlio crotals, or castagnets, formed of wooden shells.

Above Picture: Kylix by Douris. Above is an Ornamental Manuscript Basket.

Above Picture: From the Kylix of Douris. A Writing-Roll, a foldet Tablet, a Ruling Square, etc.

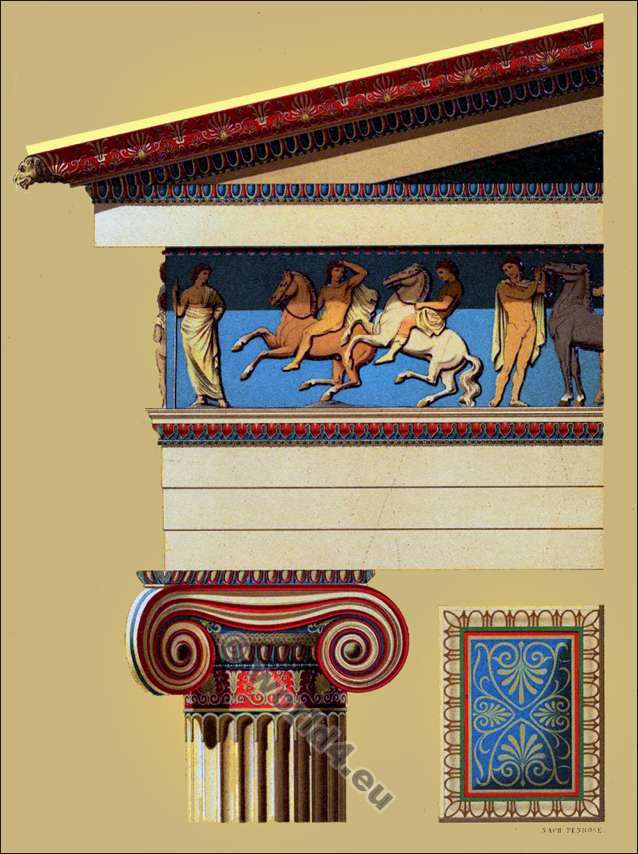

With respect to Grecian architecture, I shall only observe that the roofs and pediments of buildings were generally very richly fringed with tiles of different shapes to turn off the rain, and with spouts of various forms to carry off the water. The Sarcophagi, made to imitate the forms of houses, generally had covers wrought in imitation of those roofs.

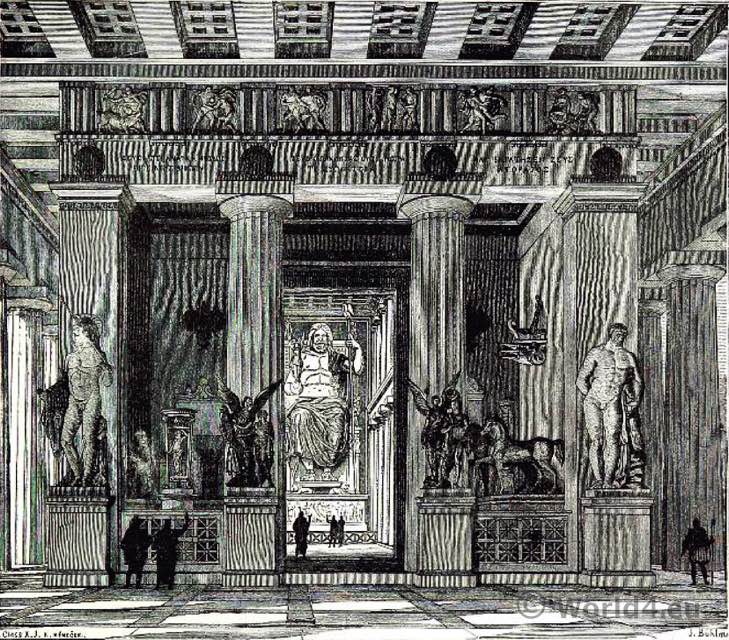

Terms, or square pillars, first only surmounted with heads of Mercury, from whom they derived their name, afterwards with those of other gods, of heroes, of statesmen, and of philosophers, were much used for the division and support of book-presses, of galleries, of balustrades, of gates, and of palings. Tripods, some of marble, and with stationary legs, others of metal, and with detached legs, made to unhook from the basin and to fold up by means of hinges and sliders, were in great request both for religious and for domestic purposes; as well as candelabra and lamps, either supported on a base or suspended from a chain.

To afford repose to the frame, the Greeks had couches covered with skins or drapery, on which several persons might lie with their bodies half raised; large arm-chairs, with foot-stools, called thrones; other more portable small chairs, divested of arms, and with legs frequently made of elephants’ tusks; and, finally, stools without either arms or backs, but with legs imitated from those of animals, and made to fold up.

Related: A collection of Greek Ornaments by Owen Jones

Endless was the variety of Greek vases for religious rites and for domestic purposes. Among the most singular was the rhyton, or drinking horn, terminating in the head of some animal. These vessels depended for their beauty on that elegance of outline which may make the plainest utensil look graceful, and not on that mere richness of decoration which cannot prevent the most costly piece of furniture, where the shape is neglected, from remaining contemptible to the eye of taste.

(1)* No name has been assigned to this well-known portion of Grecian female attire. By some writers it has been confounded with the peplum. There were two other upper garments, called the ampecone and the anahola, of which we have no distinct description. One of these may perhaps have been the square bib above mentioned.

(2)* Leopard or panther skin, as it is uniformly spotted and not striped.

(3)* The blade was leaf-shaped, and, according to Homer, generally of brass; the hilt was embellished with studs of gold and silver, and the scabbard richly adorned with the same precious metals, The sheath of Agamemnon’s sword was all of silver. Iliad, lib, xi.

By Thomas Hope.

HISTORY.

It is indispensable to situate precisely in history and clearly to define the place round the Mediterranean Sea in which grew and developed the Greek Empire and its colonies. Such preliminary notions are necessary for a right understanding of the evolution of the sumptuary arts of Greek Antiquity. Thence, indirectly, sprang the Greco-Latin art, i. e. the Roman, the Italian, the Spanish, the Gallic, the French, etc.

The people of Lydia, as well as those of Gonia and of Hellas, the Northern Aryans, Cretans, Etruscans, Archaeans and Dorians, gave birth to the earliest Greeks.

Greece may then be subdivided into: primeval Greece, Mycenae Greece, epic Greece, archaic Greece, the Greece of Athens, of Sparta, of the age of Pericles, then Greece under the Persians. After comes the influence of Rome, the decay of Greece, and her fusion into the Roman Empire into which she inculcates her refined tastes and sumptuary arts.

The formation of Greece may approximately be fixed about the year 2400 B. C. A rapid glance over the following little chronological table will no doubt prove helpful to our readers.

Pre-history; 2400 B. C. to 507 B. C.

War between the Medes and the Athenians; 499 to 438 B. C.

Intestine strifes; 431 to 362 B. C.

Macedonian supremacy ; 360 to 323 B. C.

Kingdom of the Hellenes and its decay; 323 to 146 B. C.

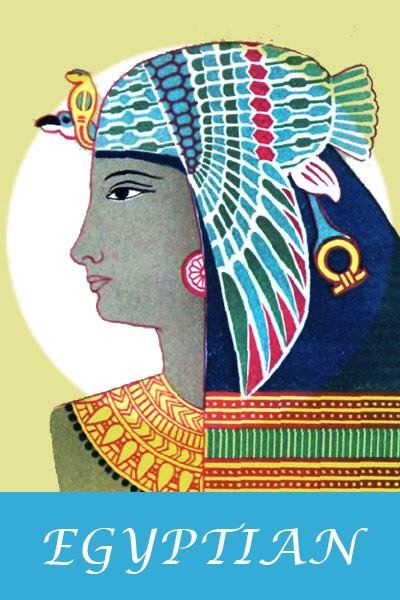

The Greek civilization began in Crete, an island in the Aegean Sea, in the 22nd century before our era. About the same epoch flourished the Middle Empire of Egypt, after the 1st Dynasty, whilst the Hebrew Patriarchs were settling in Syria and the Kings of Elam or Susa were fighting the Assyrians.

The Cretans were sailors like the Phoenicians, artisans and merchants at the same time, artists and manufacturers of vases, and greatly given to the practice of athletic sports. Their capital town was Knosse, with the palace of King Minos, and their civilization flourished from the year 2400 BC. to about the year 1400 B. C.

The Hellenes, a nation of invaders probably Aryans from the North, made inroads into Greece. They were also called Acheans, and about 1500 B. C. they founded Mycenae. After the Hellenes came the Dorians. The years rolled on, and the Mycenaean civilization being broken down by successive invasions, the people were emigrating into Asia Minor, when, about the 9th century, there appeared an embryo of Greek civilization. Then took place the eventful Trojan War, recounted in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

EXPANSION

It was at this period that these succeeding hordes of invaders, settling south of the Balkans in the scattered isles and along the coasts, formed the Greek nation. Like the Phoenicians, these Greeks established colonies and trading centres. There were several distinct Greek settlements: Greater Greece (South of Italy and Sicily), an Asiatic Greece consisting of Eolide, Ionia, and Doride; then, about the year 500 B. C., some Asiatic Greeks, or Phoenicians, settled at Marseilles.

RELIGION

The religion of the Greeks had a considerable influence on their dress, for the Greeks liked to personify their gods as beautiful women and handsome men, gorgeously dressed. One of their earliest shrines is to be found in the island of Delphi, where rose the temple of Apollo. The Greeks occasionally summonned other nations to huge religious associations called “amphyctnia”.

CAPITAL

The first, a somewhat warlike city, was Sparta in Laconia in Peloponessus where the Dorian element predominated. Sparta reached the highest point of its fame about the 9th century under the legislature of Lycurgus. The population of Athens was Ionian and consisted of agriculturalists, manufacturers and trading seamen. One of the best known Athenians of the time was Solon; (594 B. C.). Athens was pre-eminently a democracy as Phoenicia had been and as Rome was subsequently to become.

THE MEDES

In the 5th century (499 B. C.) Darius attempted to conquer Athens but the Athenians were victorious at Marathon (490 B. C.). The successor of Darius, Xerxes, broke through the Thermopylae and took Athens, but the Greeks destroyed the Persian fleet at Salamis in 480. The Medic war was concluded about the year 448 or 465 B. C.

PERICLES

The illustrious Pericles (449-429) ruled over the country in a wonderful way, giving it that matchless splendor whose light still shines in our modern arts so many centuries later. Under him it was that Athens was embellished, the Acropolis filled with buildings and the famous Parthenon erected with the friezes of the Parthenon that were found on it. We have reproduced many of the costumes of these famos women in the illustrations in this volume. As Napoleon was seconded in his artistic reproductions by the painter David, so was Pericles assisted by Phidias.

RIVALRY

The realm or empire of Greece then consisted of a great number of little towns or independent states, according to the democratic conception, whose rivalry was a cause of constant discomfort, and at last of ruin, on account of the incessant struggles of parties and doctrinarians.

At the beginning of the 3rd century, Thebes in Egypt temporarily formed part of the Greek Empire, but the King of Macedonia, about the year 222, regained his protectorate over Greece.

Then the Roman armies marched against Macedonia and destroyed its power, whereat the Greeks greatly rejoiced. But this was only a prelude to their own misfortunes, for between 196 and 146 the Roman tutelage weighed more and more heavily upon them so that, one century before the Christian era, Greece was comprised within the Roman Empire. Her high culture alone served as an intangible model, first to the Roman, next to the Latin and eventually to the whole European civilization.

The chronological landmarks in Greek civilization are therefore: its establishment in Greece about the year 2400, the foundation of Athens about the year 594, the advent of Pericles in the year 449 the expedition into Sicily in 415, the death of Socrates about 399, the liberation about 379, Philip of Macedonia before Byzantium in 340, the advent of Alexander of Macedonia in 336 and his campaigns in Egypt, Asia and India; he died, murdered, in Babylon in 323; the death of Demosthenes in 323 when the Diadochi proclaimed themselves kings, the first apparition of the Gauls in 197, and the sacking of Corinth in 146 which resulted in the complete downfall of Greece.

THE WOMEN

The Spartan maidens were brought up as severely as the young men, and dressed in the same way. They all wore the short tunic stopping at the knee, Laconian fashion, as is to be seen in the statue of Artemis. They all practised sports, unlike the Athenian Girls who remained at home.

Here is a summary of the phases of Greek art from the remotest antiquity.

Its sources may be traced to Phoenicia and the Isles of Cyprus and Crete (22nd century B. C.).

Then it was from Phrygia, Lydia, Caria, and Persia that the embryonic Greek art began to develop.

Greek art begins in primeval Greece with the city, the inhabitants and artisans of Mycenae creating the Mycenaean art (16th century B. C.). But it was principally in the 20th century and onwards, in and about The palace of Knossos, which city was destroyed about 1400, that Greek art, and especially the sumptuary art, began to show new and rapid development.

In the 18th century, whilst the Hyksos or” foreigners” were invading Egypt, at the same time as the Hebrews from Syria, the Achaeans were invading Greece.

Mycenaean kings reigned throughout the 16th century, followed by invasions of the Hellenes and the Ionians. In the 13th century the Dorians overran Greece and in the 12th the Achaeans emigrated into Asia Minor.

From the 10th century onwards civilization developed more and more in Greece while Egypt was being parcelled out. In the 9th century Lycurgus gave Sparta a legal code and then Greece began to enter upon the period of her greatest fame.

Years pass away and we discover suddenly an archaic Greece where all the sumptuary and the industrial arts meet together and florish: painting, sculpture, fine pottery and ceramic, and weaving.

Greek art was then at the moment of its greatest purity, and it required the upheavals caused by invasions of the Persians in the 6th century, of the Macedonians in the 4th, and the depradations of the Roman in the 2nd to dislocate its wonderful structure, modifying it and giving it a strange exotic impulse that will lead us to the Greco-Roman period.

Source:

- Costume design and illustration by Ethel Traphagen. New York, London: John Wiley & sons, inc. 1918.

- History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

- How Greek Women Dressed. By Professor G. Baldwin Brow. The Burlington Magazine 1905.

- Costume of the ancients by Thomas Hope & Henry Moses. London: Printed for William Miller by W. Bulmer, 1809.

- A History of costume by Carl Köhler. Edited and augmented by Emma von Sichart. Translated by Alexander k. Dallas M.A.Lecturer in German In Heriot-Watt College Edinburgh, 1916.

- A cyclopedia of costume, or, dictionary of dress, including notices of contemporaneous fashions on the continent; a general chronological history of the costumes of the principal countries of Europe, from the commencement of the Christian era to the accession of George the Third, by James Robinson Planché. London Chatto and Windus 1876-79.

- Le costume, les armes, les bijoux, la céramique, les ustensiles, outils, objets mobiliers, etc. : chez les peuples anciens et modernes by Friedrich Hottenroth. Paris: A. Guérinet, 1896.

- Costume Design: History of the Traditional Costume and the Apparatus of the Peoples of Antiquity by Hermann Weiss.

- Leben der Griechen und Römer by Ernst Karl Guhl, Wilhelm, David Koner, Richard Engelmann. Berlin, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1893.

Related

- Greece women’s costumes. The chiton, strophion, make-up.

- The Women’s toilet of ancient Greece. Cosmetics, beauty products.

- The Chlamys, the Petasos, the Himation, the Chiton. Helmets.

- Ancient Greece. Table manners. Meals, Banquet, Table Equipment.

- Hairstyles and headgear in ancient Greece. Historical Greek fashion.

- Greek women after the figures from Tanagra and Asia Minor.

- Lyras and flutes. About the musical instruments of ancient Greece.

- Warriors of heroic and historical time. Leaders and Soldiers.

- Greek Military of Antiquity. Different types of Chariots and Armor.

- Greco-Roman Antiquities. Pompeian style. Decorative Architecture.