Petra, a ruined site in what is now Jordan, was the capital of the Nabataean Empire in ancient times. The Al-Khazneh (Pharaoh’s treasure house’) is a mausoleum carved out of the rock by the Nabataeans in the ancient city of Petra in present-day Jordan. It is located opposite the entrance to the Siq, the gorge that is also the entrance to the rock city.

The building was named “Pharaoh’s treasure house” by the Bedouins. They suspected rich treasures in the large urn on top of the façade. However, the building is a burial and cult site. The façade is probably the most famous in the city of Petra.

Al-Khazneh.

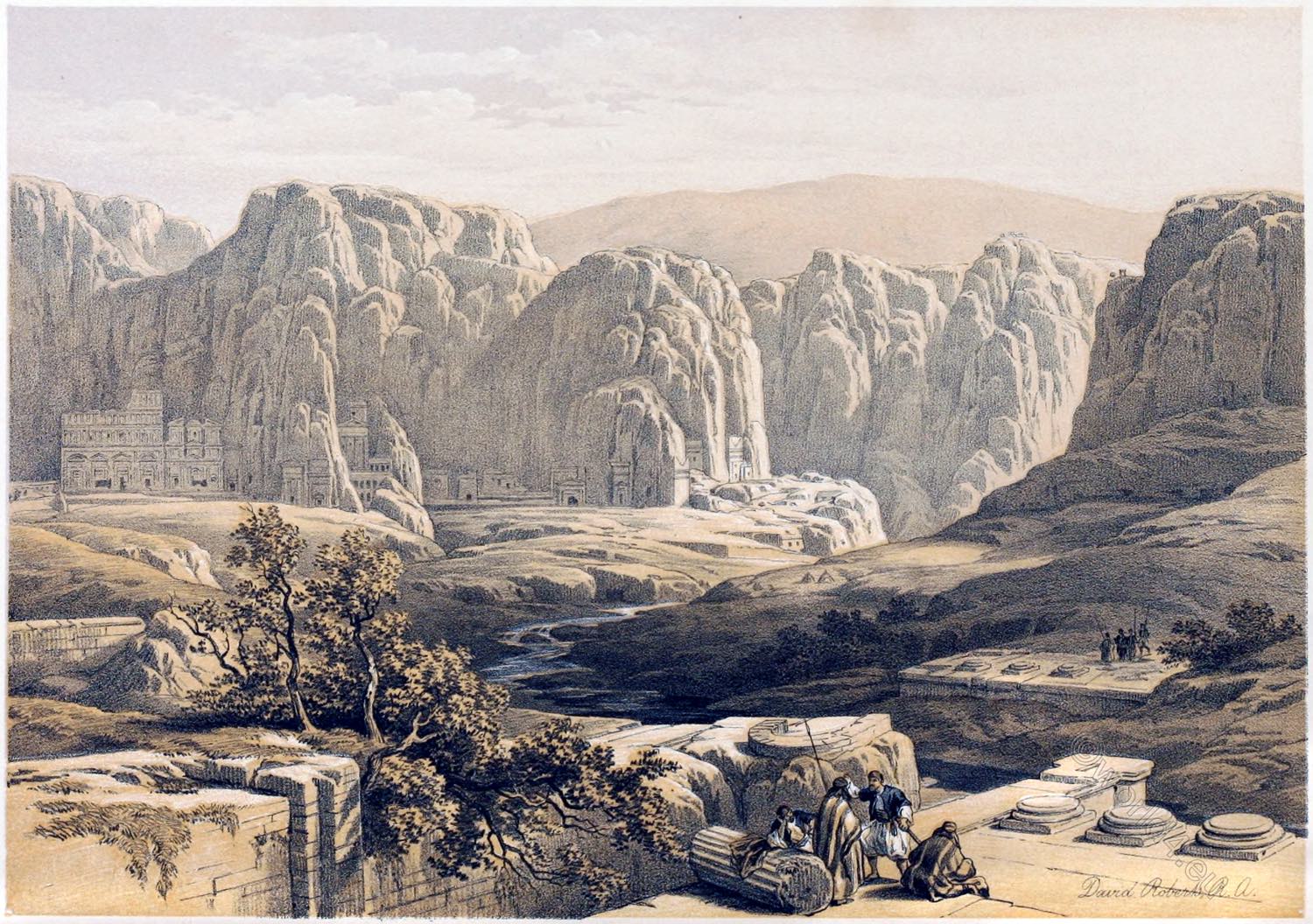

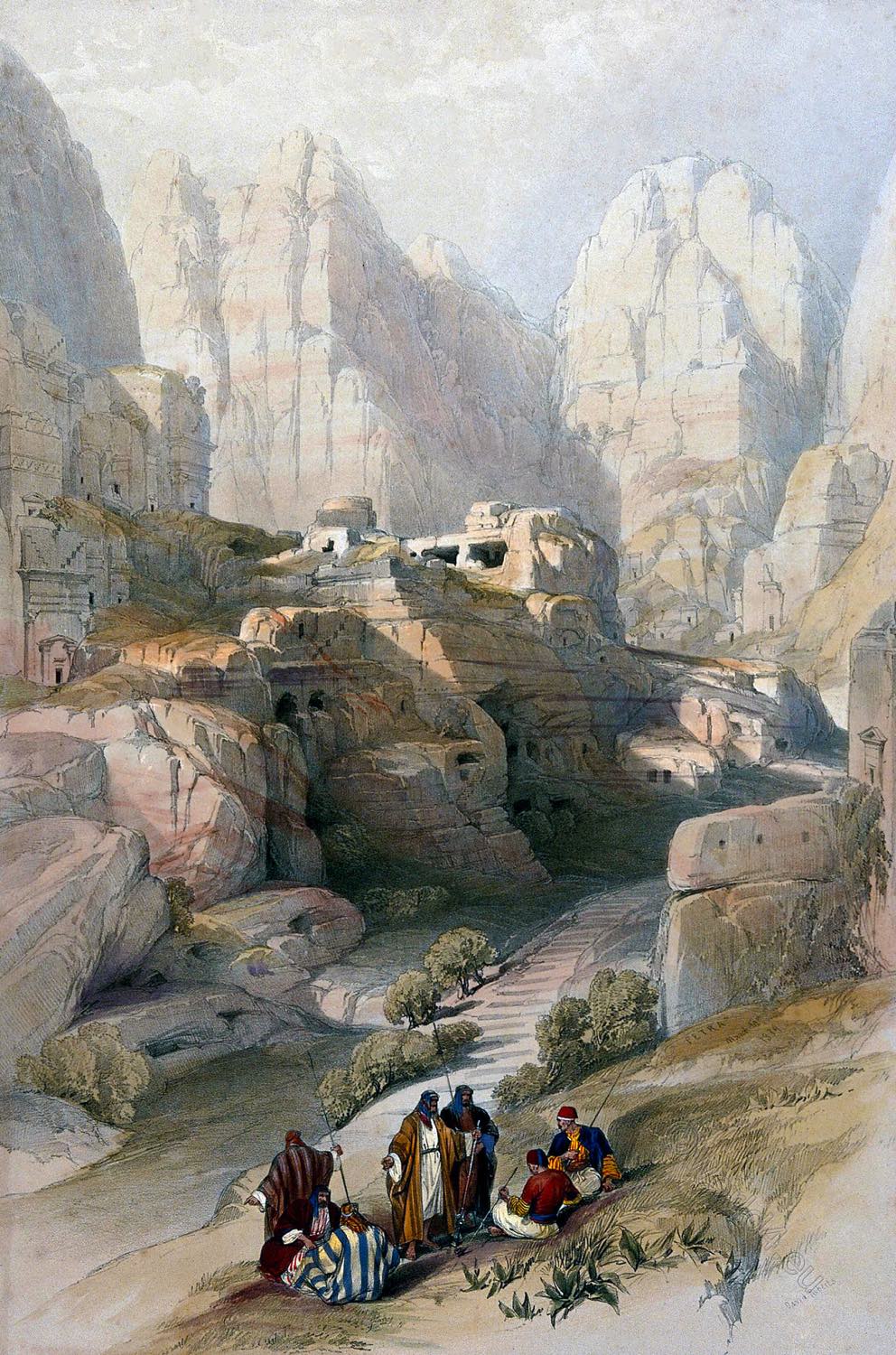

The first object which meets the eye on the approach to Petra is a range of red sandstone cliffs, apparently impenetrable; but the brook which flows into the centre of the City passes through a narrow cleft, hidden behind a projection of the rock. Here is the opening of the extraordinary chasm, which anciently formed the only avenue to the City on this side. This is the Sik of Wady Mousa (the Valley of Moses).

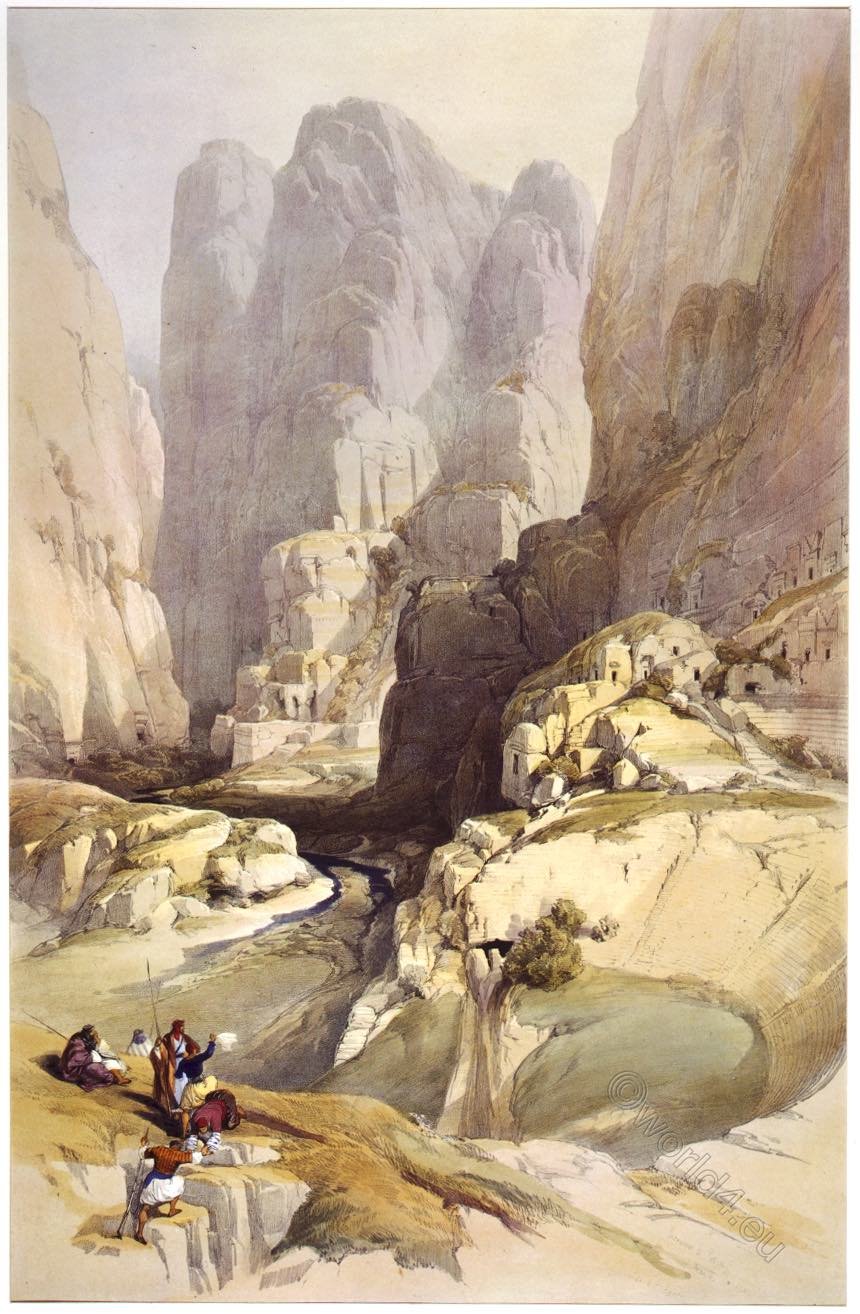

The whole chasm exhibits the traces of a people lavish of ornament. A few steps beyond the entrance, a light and lofty arch crosses it, with niches sculptured in the rock beneath, probably once intended for the reception of statues. The passage varies from 12 to 40 feet; the sides are perpendicular, rising from 80 to 250 feet, and sometimes almost shutting out the sky. The fissure continues to descend, and the brook, which flows through its whole distance, fills it with vegetation; oleanders crowd it; wild figs and tamarisks start from the crevices of the rock, and it is festooned with creeping plants.

The sides of the chasm exhibit continually the indefatigable taste and labour of this people of sculptors. Niches for statues, and tablets, evidently for bas-reliefs and inscriptions, are cut in the rock, and the greater part of the whole passage must have exhibited the appearance of a statue-gallery. To the stranger entering by this path, when Petra was in its day of power, the sudden contrast between the savage dreariness of the Desert, and the luxurious beauty and various magnificence of the City, with both its beauty and magnificence animated by the multitude from all regions, which then crowded its streets, its temples, and its theatres, must have been more like the work of magic than of man.

The entrance winds much, and other large fissures open from the sides, thus varying this most singular avenue. “The character of this wonderful spot, and the impression which it makes,” says a writer, by no means idly addicted to emotion, 1) “is utterly indescribable. I had visited the strange sandstone caves and streets of Adersbach, and wandered with delight through the romantic dells of the Saxon Switzerland. But they exhibit few points of comparison. All here is on a grander scale. We lingered along this superb approach, forgetful of everything else, and taking no note of time. The length is a long mile; we were forty minutes in passing through it in this desultory manner.”

The Sik terminates in a broader chasm, opening at right angles with it, and passing to the north-west. From this point the most perfect and beautiful relic of the City bursts upon the view—the Al-Khazneh (the treasure), a name given to it by the Arabs, from a tradition that it contains the treasure of Pharaoh, to whom they attribute the building of all extraordinary tilings.

The Al-Khazneh strikes all eyes, and the advantage of its position, which has greatly protected it from the effect of time, presents it in almost the perfection of its first day. It is universally acknowledged to be exquisitely beautiful, and to produce a more powerful impression than any surviving monument even of Greece or Rome. Its style wants classic purity, but the elegance of the general effect makes errors in detail trivial. The stone is of a rich rose colour: the symmetry of its facade is perfect; its preservation is almost complete. But the whole skill of the architect seems to have been devoted to the first impression.

The interior is narrow and simple; from the vestibule the door opens into a plain, lofty room, excavated in the rock; behind this is another smaller, and small lateral chambers open from the large room and vestibule. Was this a Temple or a Tomb? The general opinion is that it was the former. Yet would a Temple be placed in the very rush and torrent of public life, or in a chasm which scarcely allowed space for the access of the worshipper, and almost prohibited the forms of sacrifice? But it stands in a valley of tombs, and is only more stately than them all. If the genius of a splendid City, a thousand years past away, could be enshrined, the memory of the loveliness and grandeur of Petra could not have been transmitted by a nobler Mausoleum.

1) Robinson, Biblical Researches, ii. 518.

Source: The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia, by David Roberts (British, 1796-1864), George Croly, William Brockedon. London: Lithographed, printed and published by Day & Son, lithographers to the Queen. Cate Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1855.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.