The city of Posidonia or Paestum

Paestum is a ruined site recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Campania region in the province of Salerno in Italy. The site belongs to the municipality of Capaccio. The place is situated in a plain about 35 km south of Salerno. It was built 2 km from the Mediterranean coast. This shows that the Greeks did not want to establish a port here as a trading base, but that they had the cultivation of the fertile soil in mind. It is protected behind a lagoon, where the harbour was probably located in former times. Paestum is bordered to the east and south by the Cilento Mountains. To the north, there is a natural barrier in the form of the Sele.

PAESTUM.

by James Hakewill.

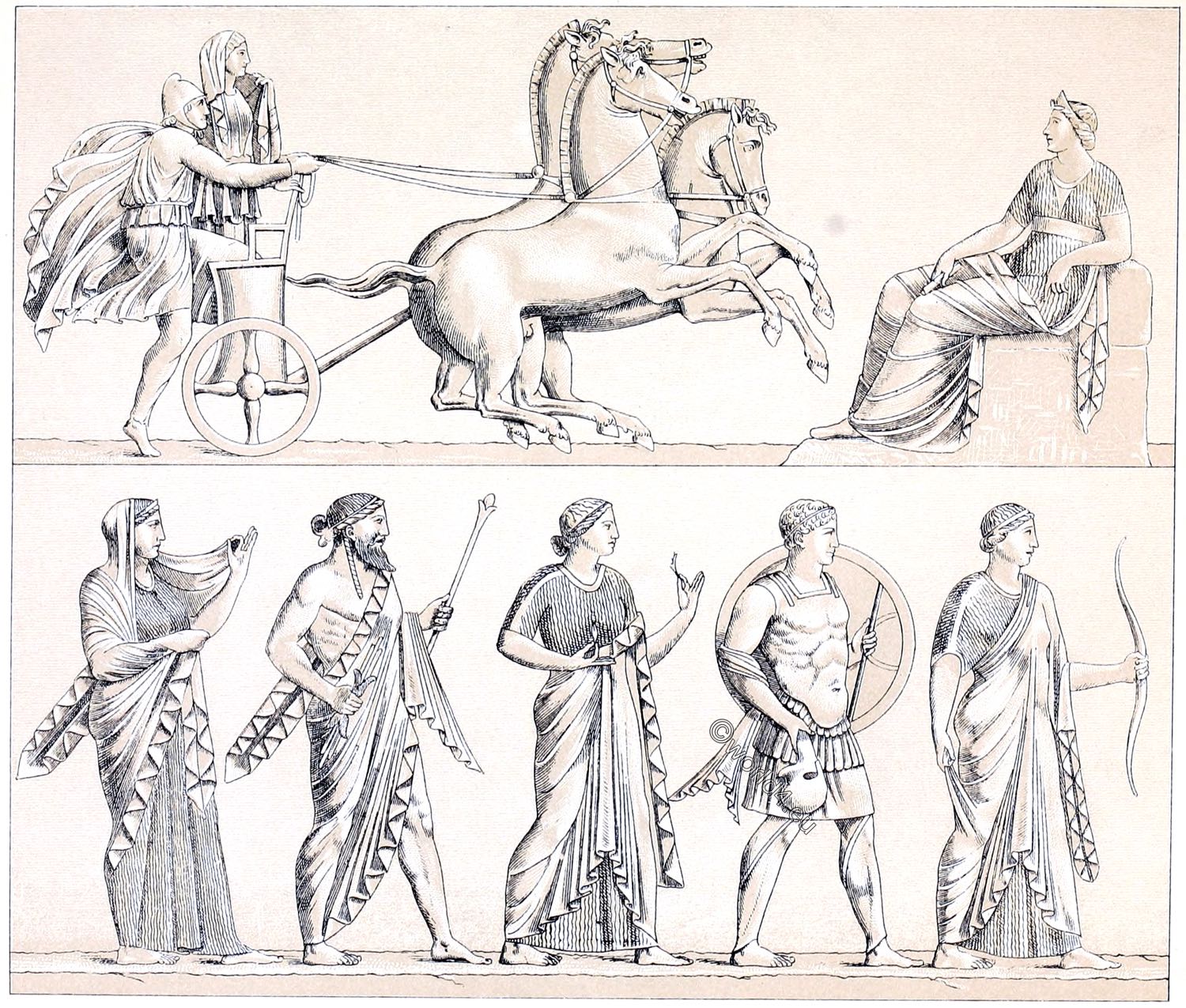

We trace the history of the city of Posidonia or Paestum, by medals and other ornaments found on the spot, from the earliest ages: first the Dorians (or, as P. Paoli supposes, the Etruscans) possessed the place, then the Sybarites, then the Samnites, and subsequently the Romans but no light whatever is; thrown on the aera of the foundation of the stupendous temples which appear in this View; nor is it on any other ground, than by a comparison of their style with that of the temples in Sicily and Attica, that they have been pronounced to be of Grecian origin.

This magnificent city was burnt and laid waste by the Saracens in the year 915; and Robert Guiscard, the Norman, completed its desolation in the following century, by transporting columns and marbles from hence (according to the Grecian fashion of the day), for the purpose of decorating the churches which he was employed in erecting. The circuit of its walls extend upwards of two miles and an half; the walls are built with large stones of irregular shapes, some square, others hexagonal some of them measure more than twenty feet in length; there are the remains of square towers, built at certain regular intervals; also of an inner wall, appearing to have been constructed for the purpose of rendering the defense of the place more effectual.

The entrances were four, of which that on the north is in the best state of preservation: the arch must have been upwards of fifty feet in heights: two bas-reliefs are remaining; one representing (as is supposed) a siren, the other a dolphin, not inappropriate symbols of a maritime people. On this side also are the ruins of an aqueduct that conveyed water to the town from the heights of Capaccio, whose situation may be distinguished in this View, rising over the temples on the right.

At a short distance from the western gate are the remains of some antique sepulchers, covered interiorly with an hard stucco, and embellished with paintings. Several vases and other curiosities of undoubted Grecian workmanship have been discovered here, and are now to be seen in the royal museum at Portici.

With regard to the architecture of the temples, the best information may be found in Mr. Wilkins’s valuable work on the Antiquities of Magna Graecia, where the detail of the parts, together with much general information, is given. Amongst other things, he draws a very interesting comparison between the proportions of these temples, and the most ancient of which we have elsewhere notice; that of Jupiter Panhellenius in AEgina, and the temple of Solomon at Jerusalem, of which an accurate description is afforded in the first book of Kings, c. vi.; both of the latter were founded in the eleventh century before the Christian aera, and those of Paestum at a date perhaps not very far distant; reasoning on this head, he says, “so great a resemblance will be found upon investigation “ to exist between them, as to afford a presumptive proof that the architects, “both of Syria and Greece, were guided by the same general principles in the “distribution and proportion of the more essential parts of their buildings.

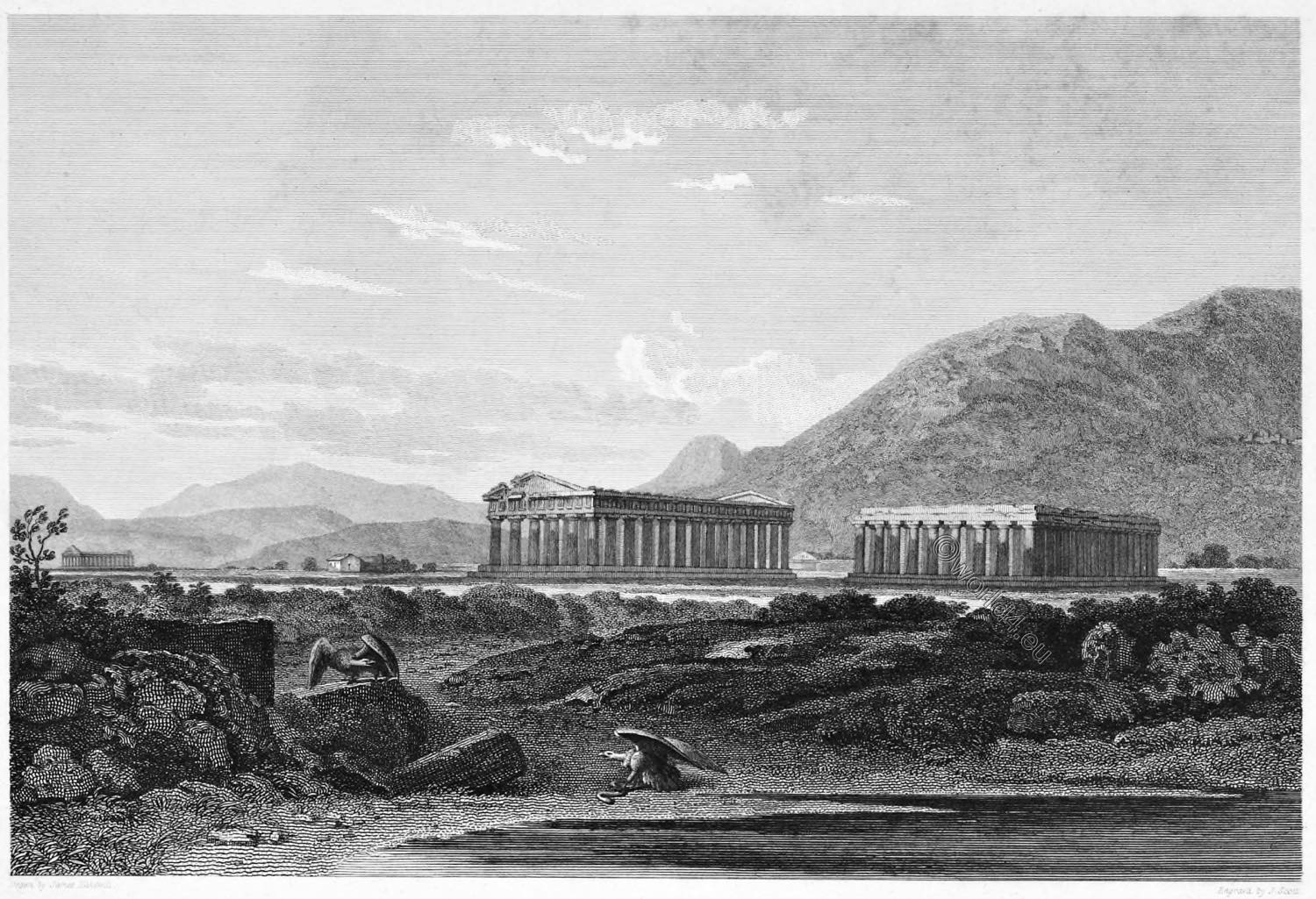

The two temples usually bear the names of Neptune and Ceres, and the third building is called the Portico, and was probably destined for public meetings of the people.

The Temple of Neptune at Paestum.

With Shelley in Italy

Temple of Neptune at Paestum. Letter from Naples. The Year 1818. Shelly in Italy.

We slept at Salerno, and the next morning before day- break proceeded to Posidonia. The night had been tempestuous, and our way lay by the sea sand. It was utterly dark, except when the long line of wave burst, with a sound like thunder, beneath the starless sky, and cast up a kind of mist of cold white lustre. When morning came, we found ourselves traveling in a wide desert plain, perpetually interrupted by wild irregular glens, and bounded on all sides by the Apennines and the sea. Sometimes it was covered with forest, sometimes dotted with, underwood, or mere tufts of fern and furze, and the wintry dry tendrils of creeping plants. I have never, but in the Alps, seen an amphitheatre of mountains so magnificent.

After traveling fifteen miles we came to a river, the bridge of which had been broken, and which was so swollen that the ferry would not take the carriage across. We had, therefore, to walk seven miles of a muddy road, which led to the ancient city across the desolate Maremma. The air was scented with the sweet smell of violets of an extraordinary size and beauty. At length we saw the sublime and massy colonnades, skirting the horizon of the wilderness.

We entered by the ancient gate, which is now no more than a chasm in the rock-like wall. Deeply sunk in the ground beside it, were the ruins of a sepulchre, which the ancients were in the custom of building beside the public way. The first temple, which is the smallest, consists of an outer range of columns, quite perfect, and supporting perfect architrave and two shattered frontispieces.

The proportions are extremely massy, and the architecture entirely unornamented and simple. These columns do not seem more than forty feet high, 1) but the perfect proportions diminish the apprehension of their magnitude; it seems as if inequality and irregularity of form were requisite to force on us the relative idea of greatness.

The scene from between the columns of the temple 2) consists on one side of the sea, to which the gentle hill on which it is built slopes, and on the other, of the grand amphitheatre of the loftiest Apennines, dark purple mountains, crowned with snow and intercepted there by long bars of hard and leaden-coloured cloud.

The effect of the jagged outline of mountains, through groups of enormous columns on one side, and on the other the level horizon of the sea, is inexpressibly grand. The second temple 3) is much larger, and also more perfect. Beside the outer range of columns, it contains an interior range of column above column, and the ruins a wall which was the screen of the penetralia. With little diversity of ornament, the order of architecture is similar to that of the first temple. The columns in all are fluted and built of a porous volcanic stone which time has dyed with a rich and yellow colour.

The columns are one-third larger, and like that of the first, diminish from the base to the capital, so that, but for the chastening effect of their admirable proportions, their magnitude would, from the delusion of perspective, seem greater, not less, than it is; though perhaps we ought to say not that this symmetry diminishes your apprehension of their magnitude, but that it overpowers the idea of relative greatness, by establishing within itself a system of relations destructive of your idea of its relation with other objects on which our ideas of size depend. The third temple is what they call a Basilica; three columns alone remain of the interior range; the exterior is perfect, but that the cornice and frieze in many places have fallen. This temple covers more ground than either of the others, but its columns are of an intermediate magnitude between those of the second and the first.

We only contemplated these sublime monuments for two hours, and of course could only bring away so imperfect a conception of them as is the shadow of some halfremembered dream.

1) The columns of the Temple of Neptune are 29feet; of Basilica, 21 feet 6 in. high.

2) Known as Temple of Ceres.

3) Known as Temple of Neptune.

TEMPLES OF PAESTUM

by George Newenham, 1841.

"A fair and sumptuous city then stood here, Lifting its marble forehead o'er the sea. And glittering in the sunny atmosphere. With calm, white masonry." Mary Howitt

There is not a scene, in all the sunny region of fair Italia, more sad, solitary, or singular than the desolate plain where ancient Paestum stood, the sole memorials of which are the three grand buildings called the Temples.

“Taking into view their immemorial antiquity, their astonishing preservation, their grandeur, or rather grandiosity, their bold columnar elevation, at once majestic and open, their severe simplicity of design—that simplicity in which art generally begins, and to which, after a thousand revolutions of ornament, it again returns—I do not hesitate to call these the most impressive monuments I ever beheld on earth.”*

The modern history of these beautiful architectural forms is, if possible, more wrapped in mystery than the ancient; for many centuries their very existence remained in obscurity; and though their dim gray temples are discernible with the aid of a glass from Salerno, the Calabrian road commands a distant view of them, the city of Capaccio looks down on them, yet they remained unnoticed by the best Neapolitan antiquaries down to the middle of the last century.

Whether this accident is owing to the actual ignorance or culpable indifference of learned travelers, the unsafe and lawless slate of the country, or other causes, the merit of the discovery is due to the miserable shepherds of the Paestan plain, who drew to these splendid ruins the attention of a young artist, who had thoughtlessly rambled from Capaccio in search of employment for his pencil.

The origin, founder, or destination of these magnificent monuments, has occasioned as much controversy as the cause of their concealment from observation during so many centuries of time; yet nothing is supplied by the labors of the disputants, but learned conjecture—none have been able to decide, with accuracy, to what class of buildings they belong.

Temples, Baths, or Halls?

Pronounce who can; for all that learning reap’d

From her search hath been—that these are walls.

Etymology will sustain, with equal probability, the antiquary’s choice, whether he shall assign a Phoenician, Etruscan, Dorian, or Sybaritic origin to these remains. The latter were expelled from the city and plain of Paestum by the Lucanians, who themselves deserting their conquest, left it to be colonized by the Romans. Virgil and Claudian seem to have delighted amongst its shrubberies and gardens, and to have borrowed illustrations from the biferique rosaria Paesti.

But this poetic celebrity did not avail the ancient city, which, though built in the Cyclopean manner, with huge polyhedric stones, was plundered by the Saracens, and dispeopled by the Norman ravagers. Robert Guiscard carried away the columns, sculptures, and ornaments, to embellish the church of St. Matthew at Salerno; and the sacrifices which Paestum made to his devotional inclination was more fatal to her duration than the injuries of the infidel.

These sublime structures have survived the extinction of the city in which they were once included; and, although Paoli can perceive the Tuscan order alone, he alone can perceive it, for the temples of Paestum are in the Doric style; not the Doric of the Parthenon, but perhaps a later, perhaps of the age between the Egyptian and Grecian manners, and the first attempt to pass from the huge masses of the one to the delicate gracefulness of the other. “The temples of Paestum, Agrigentum, and Athens, exemplify the commencement, improvement, and perfection of the Doric order.”

The ruins include two temples, the larger consecrated to Neptune, the less toCeres; and a basilica, or kind of paecile, divided longitudinally by a row of columns, besides a Roman amphitheatre.

Another temple, evidently of Roman origin, was discovered in the year 1830, between those of Neptune and Ceres; but the ruins are hardly sufficient to attest its original area. The three principal structures are all peripteral, the peristyles being still entire: the columns are not five diameters in height, and the intervals between closer than in the pyenostyle itself. The shafts are frusta of cones, fluted as in the Grecian-Doric; and the mouldings, with the exception of the ovolo of the capitals, are angular.

In the Paestan-Doric, the members which support are larger than those supported; the architraves higher than the frieze, the latter than the cornice; “yet these very peculiarities create such an exaggeration as awes every eye, and a stability which, from time unknown, has sustained in the air these ponderous entablatures. The walls are fallen, the columns stand; the solid has failed, the open resists.” It is impossible not to be amazed at the secret equilibrium by which these solid masses have been upheld for centuries, neither cement, iron-cramps, nor any artificial aid being discernible in maintaining their association. The other properties which they possess in common are, being built of a porous stone found near the sea-shore, and being all elevated on plateaus, or substructions, from which the columns rise directly without any pedestal or plinth.

The smallest of the temples has six columns at each end, and thirteen on each side, including the angular columns in both directions: the architrave is entire, and also the pediment at the west end. The cella occupied more than one third of the length, and had a double portico, the shafts and capitals of which, now overgrown with weeds, fill up the contracted dimensions of the interior. These temples, from the limited extent of their enclosures, rather appear to have been sanctuaries for images of the gods, into which the pontifices alone were permitted to enter, than places for all to worship in common

The Temple of Neptune is more perfect, varied, and majestic: it has two peristyles, separated by a wall; the outer having fourteen columns on each side, and six at each end or front; the inner having two stories of columns, separated only by an architrave. Of this singular design, seven columns remain at one side of the cella, and five at the other. The summit of the upper tier is somewhat higher than the external cornice, and appears, therefore, to have been intended to support a roof of gentle inclination. The foundations of the wall that enclosed the cella are distinct, as well as the opening by which a descent was effected into a spacious crypt beneath.

The largest structure, called a basilica, is unparalleled in architectural remains: it has nine columns at the ends, eighteen on each side, including those that stand at the angles, and is divided from end to end by a row of pillars, extending between the central columns at each end. The destination of this anomalous edifice has not been assigned: the terms, atrium, basilica, curia, or any other, are applied in vain, while the example remains unique. The odd number of columns in front, and the bisected cella, are so contrary to anything hitherto known, that antiquaries do not feel disposed to allow to this building the dignity of a temple. One of the most enlightened of our classical tourists—one who illumined every subject which he touched—confesses “that having exhausted conjecture, he returned to the idea of a temple: an open temple, which had no front-doors to fix the distribution of columns, a temple, perhaps, parted between two divinities, like that of Venus and Rome.”

Source:

- A picturesque tour of Italy, from drawings made in 1816-1817 by James Hakewill (1778-1843); Turner, J. M. W. (Joseph Mallord William). London: John Murray, 1820.

- With Shelley in Italy: a selection of the poems and letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley relating to his life in Italy by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822); Anna Benneson McMahan (1846-1919). London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1907.

- The Rhine, Italy, and Greece in a series of drawings from nature by George Newenham (1790?-1877). London: Fisher 1841.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.