Assyrian and Babylonian culture. Mesopotamia. Ancient Costume and Fashion History.

Babylonian and Assyrian dress by Horst Kohler

Babylonian and Assyrian dress, although simple in cut, like that with which we have hitherto dealt, had reached a high degree of excellence in respect of material and trimming. The Babylonian Empire (about 2000 B.C.) had given place to the Assyrian Empire, which by the year 1300 B.C. had become the most powerful Asiatic state, and had absorbed the entire civilization of Western Asia.

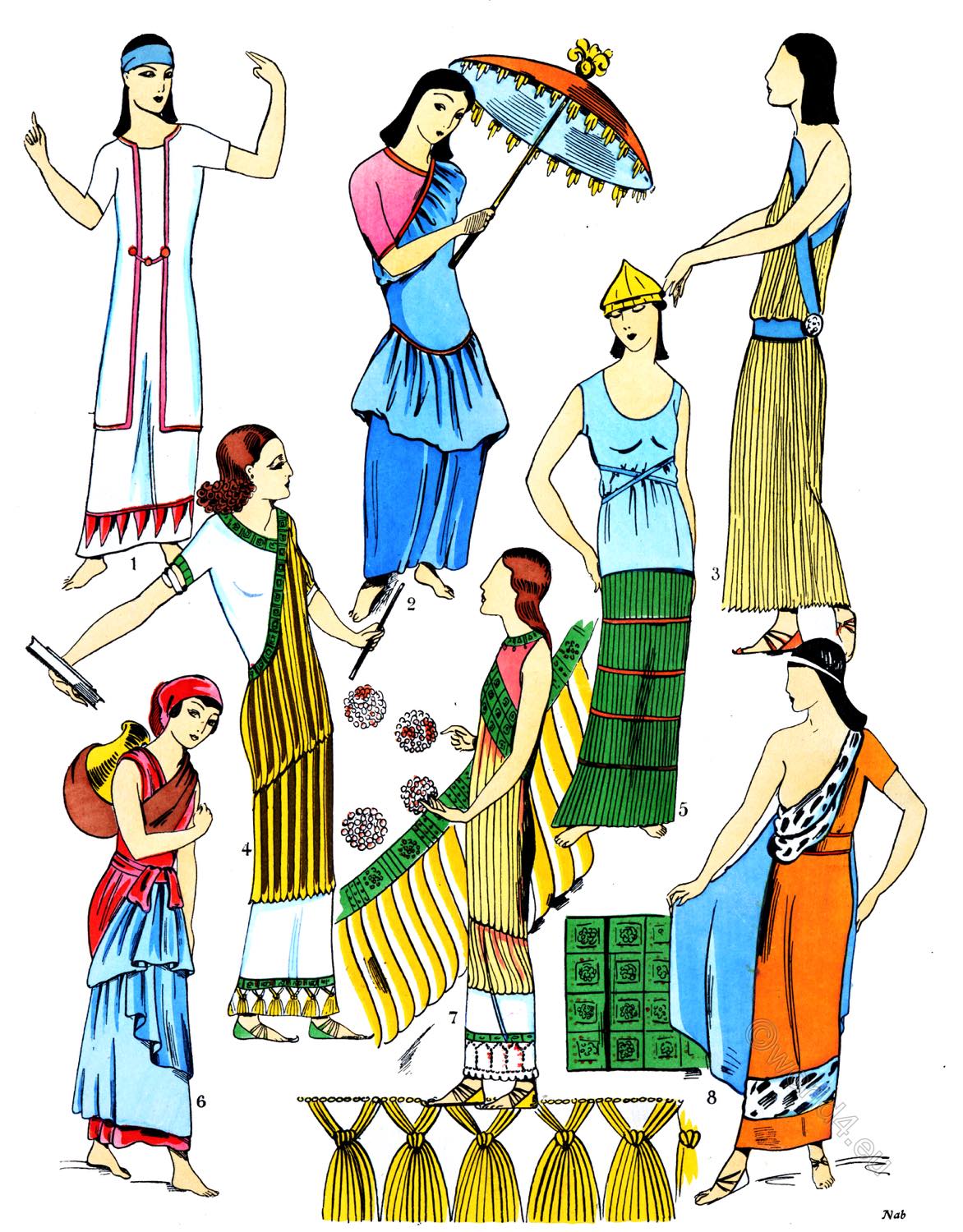

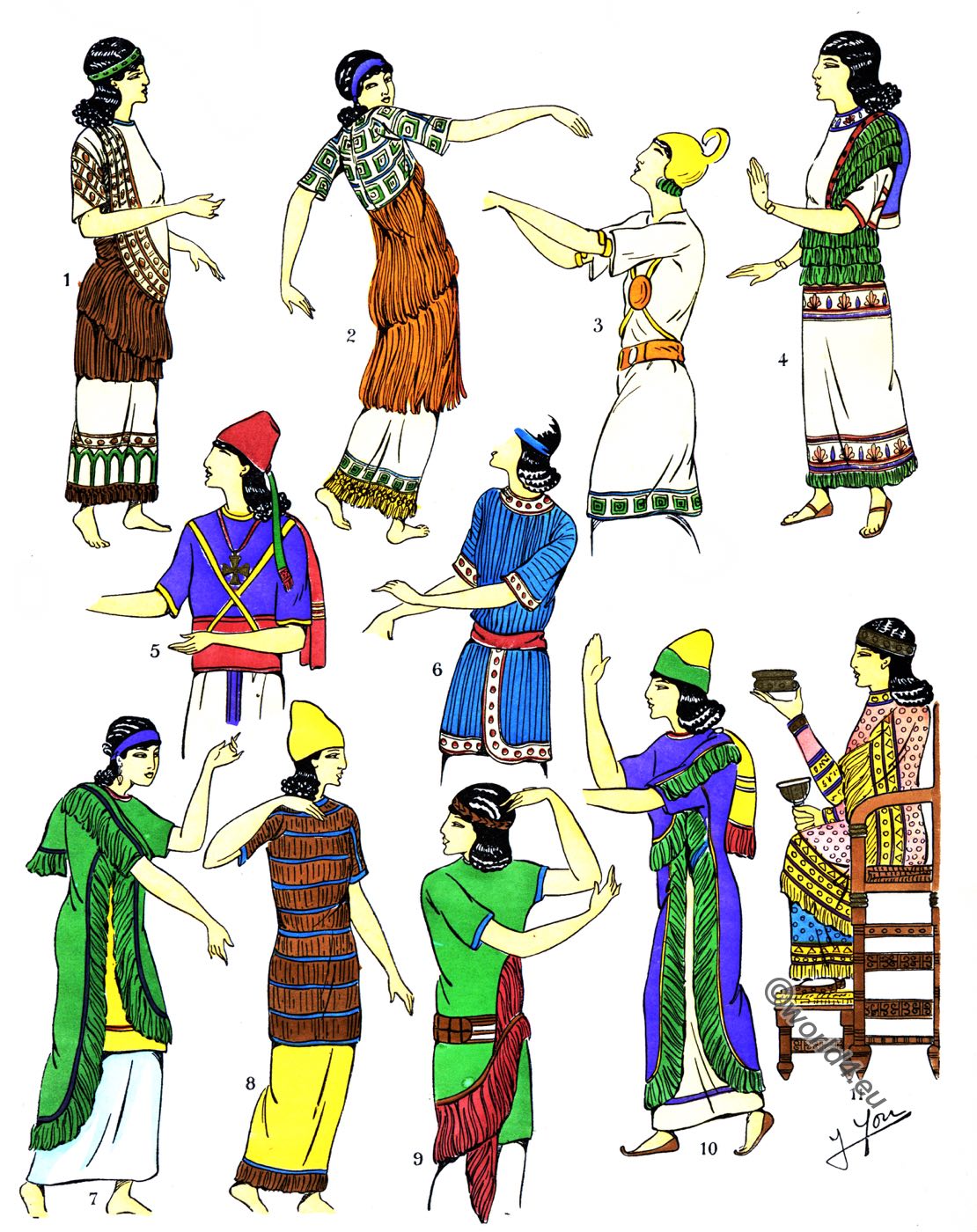

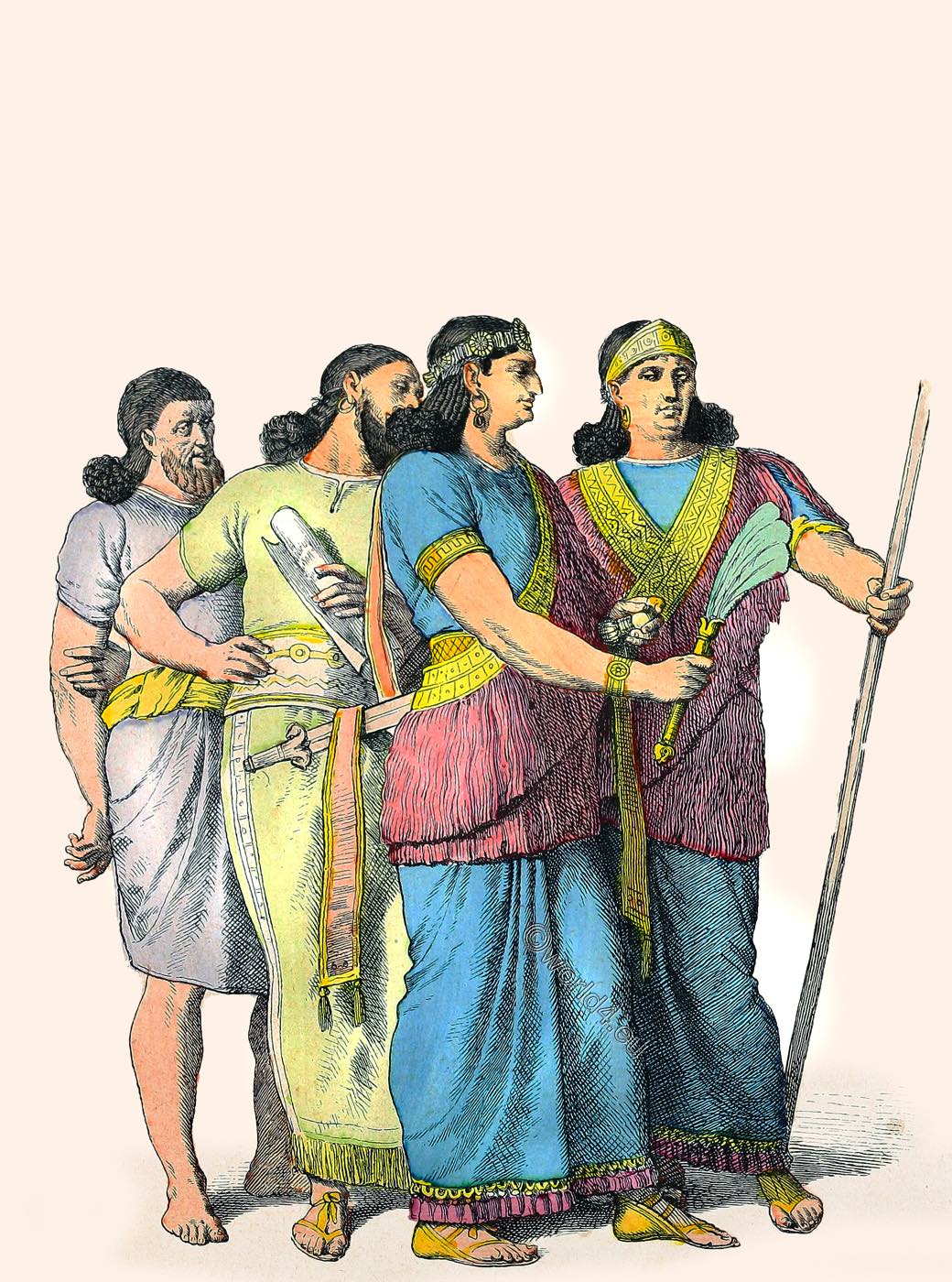

The national dress both in Assyria and in Babylonia was a shirt with short, tight sleeves, cut very like the Egyptian kalasiris. The length varied. This was the sole garment of the lower orders for both sexes. Some wore it with and some without a girdle (Fig. 34). Even during the time when the national prosperity was at its height the slaves of the nobles had no other dress than this, and, in their case, it was only long enough to reach to the knee. Men of the higher orders also wore this short-sleeved shirt, but with them it reached to the feet. Most of them wore girdles trimmed with tassels, and, in keeping with the dignity of the wearers, the garments themselves were trimmed and embroidered more or less elaborately. Even the monarch wore this costume, and, in addition to it, on ceremonial occasions he put on a cloak-like over garment, whose shape and trimming underwent many changes as time went on.

Auguste Racinet. The Costume History by Françoise Tétart-Vittu.

Racinet’s Costume History is an invaluable reference for students, designers, artists, illustrators, and historians; and a rich source of inspiration for anyone with an interest in clothing and style. Originally published in France between 1876 and 1888, Auguste Racinet’s Le Costume historique was in its day the most wide-ranging and incisive study of clothing ever attempted.

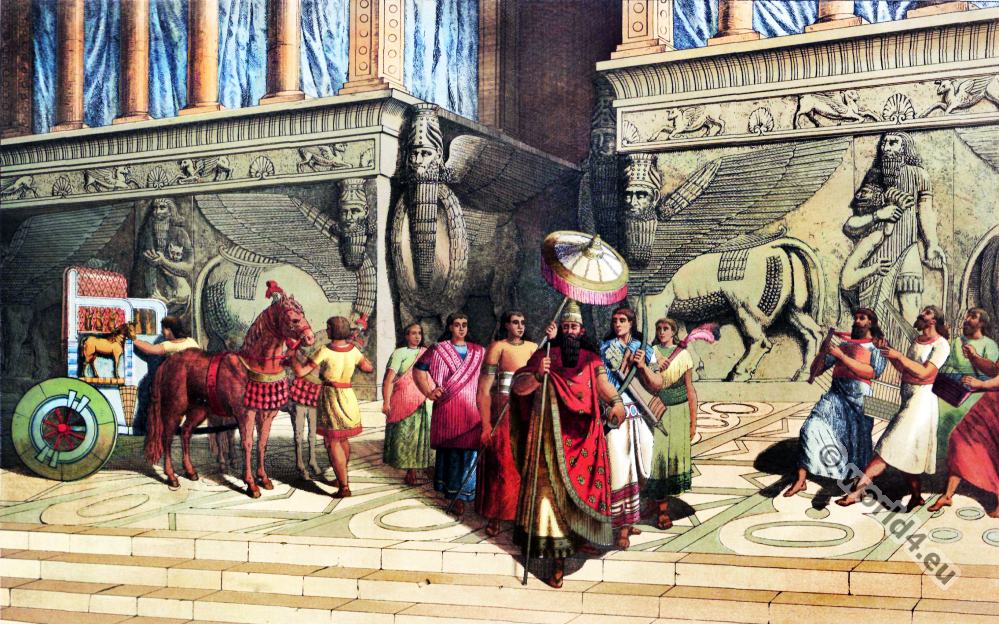

Fig. 34. National costumes of Assyria and Babylonia

In its earliest form this garment resembled the shoulder-cape that was from primitive times worn by the nobles of the various peoples (including the Aamu and Ribu) inhabiting Western Asia. It consisted of a large, oblong piece of material of varying colour and pattern. This was either drawn forward under one arm and fastened on the other shoulder with an agraffe or clasp, or openings were made in it for the head and one arm, and it hung over both shoulders, being open of course on one side. As time went on these cloaks became richer and more elaborate. The edges were trimmed with fringes and tassels. But the only change of cut was that the shoulder parts were lengthened so as to reach the middle of the upper arm. To allow this to be done the garment was made in two pieces and sewn together at the top, a hole being left for the head (see Fig. 35).

Fig. 35. Assyro-Babylonian Royal Robe

Both sides were now left open, instead of being open only at the armhole, and the front and back pieces were held together with tapes sewn for this purpose to the inside of the garment. (See Fig. 36.)

The usual badge of rank worn by all higher Court and State officials was a long fringed stole or shoulder-scarf, the ends of which were wound round the person. While rank was sometimes indicated by the amount of trimming on the full-length skirt, it was still more clearly shown by the scarf. The richness of the material and the length (as well, perhaps, as the colour of the fringes and the manner in which the scarf was worn—plain or crossed) indicated the station of the wearer. For example, a scarf with long fringes worn crossed over the breast was the distinctive mark of the prime minister, or vizier. A double scarf with equally long fringes worn crossed indicated the master of ceremonies. The king’s own personal attendants—armour-bearer, cupbearer, etc.—wore scarves with short fringes. Officials of still lower grade, like the parasol-bearer, wore no scarf at all. The monarch himself in early times donned the scarf over all his other attire, but in after days, from 750 B.C. onward, this ceased to be part of his state dress.

Fig. 36. Assyro-Babylonian Royal costume

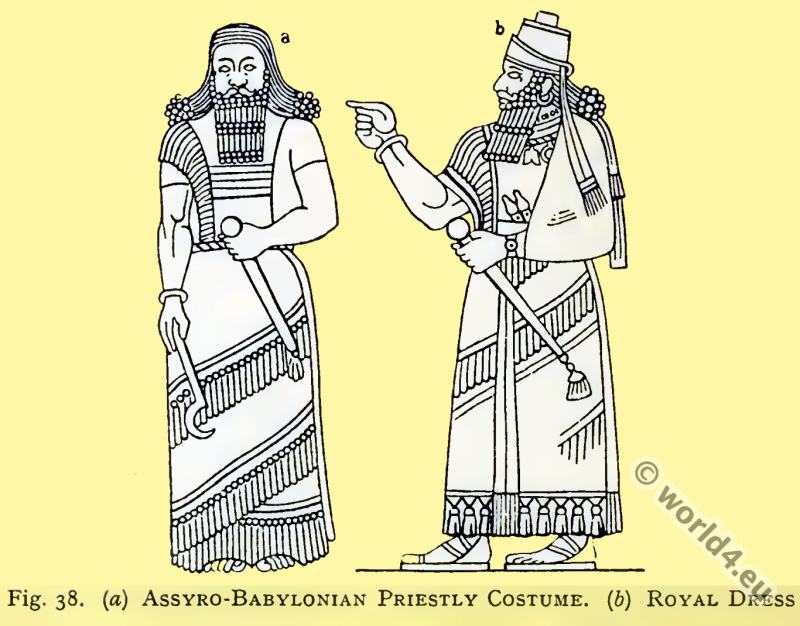

Fig. 38. (a) Assyro-Babylonian Priestly costume. (b) Royal dress.

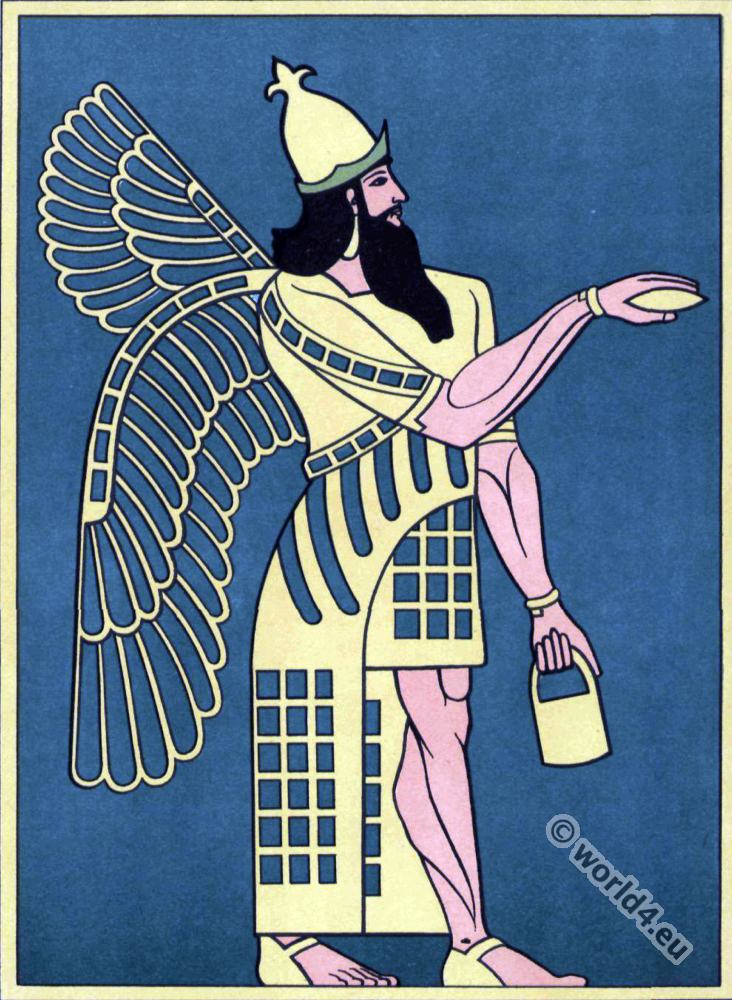

The official dress of the priests was quite unlike that of the high Court functionaries, and even the costume worn by the king as head of the priesthood was altogether distinct from that which indicated his royal rank. It is difficult to make out how far the priests’ dress differed from that of ordinary laymen in respect of material and colour, but there is no doubt that there was a difference. In any case, the official costume of the priest was not less magnificent or imposing than that of the courtier. It seems probable that a special material-bleached linen was used by the priests, and by them exclusively.

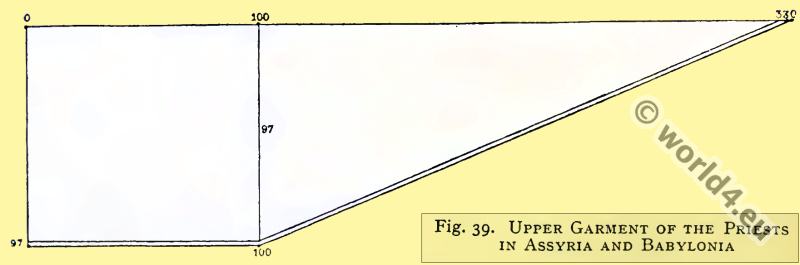

Fig. 39. Upper Garment of the Priest in Assyria and Babylonia.

There were two styles of priestly costume, used in different ceremonies. In the one case the priest wore the long, short-sleeved shirt, and over it a garment that swathed the body from the feet up to the loins or even to the shoulders. The shorter style (Fig. 38, a) was made of a piece of material in the shape of a right-angled triangle, one of the sides containing the right angle (Fig. 39) being of a length equal to the distance from the waist to the feet.

The other side was considerably longer, and the third and longest side of the triangle was fringed. The garment was put on in this way. It was spread round the person so that the longer of the two sides containing the right angle encircled the waist at an equal height all round. It was kept in place by a cord passing round the body. The fringed side thus encircled the body in an ascending spiral (The double lines in Fig. 39 indicate the sides that were fringed.).

The piece of material, embellished by an embroidered inscription and with a fringe down one side, worn on the high priest’s breast seems to have been made of thick cloth, and was hung over the shoulders, an opening permitting the head to pass through. The lower edge lay on the wearer’s back, and the whole was kept in position by a girdle.

Fig. 40. Upper Garment of the Royal Priestly Costume in Assyria and Babylonia.

The dress worn by the king at the same religious ceremony, though apparently similar to this high priest’s dress, was really very different. Whereas the high priest’s robe was triangular in shape, that of the king (Fig. 38, b) was rectangular, the two short sides being of a length equal to the distance from the loins to the feet. A piece was cut out of one of the two short sides, making two peaks, one rectangular and one triangular, the latter forming part of the lower portion of the garment and fringed all round like the bottom edge (Fig. 40).

This garment was swathed round the body as before, but in order that the bottom edge with the fringe should encircle the body in an ascending spiral the material was kept moving upward and disposed at the top in folds running obliquely round the body. These folds were concealed by a girdle. This swathing process was so carried out that the garment was pulled up across the back, and the back of the excision reached well up to the nape of the neck. The two peaks, held in position by the girdle, were then brought forward over the shoulders so that the triangular peak could be drawn over the right shoulder, covering the upper right arm, while the rectangular peak passed over the left shoulder, hiding almost entirely the upper left arm. The other type of ceremonial priestly dress also included the short-sleeved shirt as under-garment. This did not, however, reach to the feet, but only to the knee. As in all other forms of ceremonial dress, the bottom edge was trimmed with rich braid and with tassels (see Fig. 37).

Fig. 37. Assyrian or Babylonian Priest.

Fig. 41. Cloak of the Assyrian or Babylonian Priest.

The high priests, the head of whom was the king himself, wore over this a cloak-like garment cut all in one piece (Figs. 41 and 42). It was drawn through under one arm and fastened on the opposite shoulder in such a manner that the front fell back over the upper arm. On the open side the back of the cloak was tied to the front with cords sewn to the inside, their tasselled ends hanging low down. This arrangement caused the garment to fit fairly close over breast and back. There are also representations which show members of the priesthood wearing not this cloak-like upper garment, but a long apron of equally costly material.

Reaching from the hips to the ankles, it covered only the back parts, leaving in view the front portion of the short, richly embroidered shirt (Fig. 37). All the edges of this apron, except that at the top, had a double row of tassels and fringes. These were attached in such a way that the tassels hung down behind the fringes, and were therefore visible only on the inside of the garment, while only the fringes could be seen on the outside.

This apron was kept in position round the body by long cords, whose tasselled ends were long enough to reach the feet. Over the shoulders a long scarf or stole with long fringes was worn. The priests occasionally wore a garment slightly different from this one. This was merely an apron reaching from the waist to the knee, adorned with braid and tassels. It was flung round the lower trunk and thighs and kept in place by cords with tasselled ends.

Fig. 42. Priestly Robes worn by King in Assyria and Babylonia.

By Carl Köhler

Continuing

Characteristic elements of style.

Architecture, costumes, decoration, furniture, weapons.

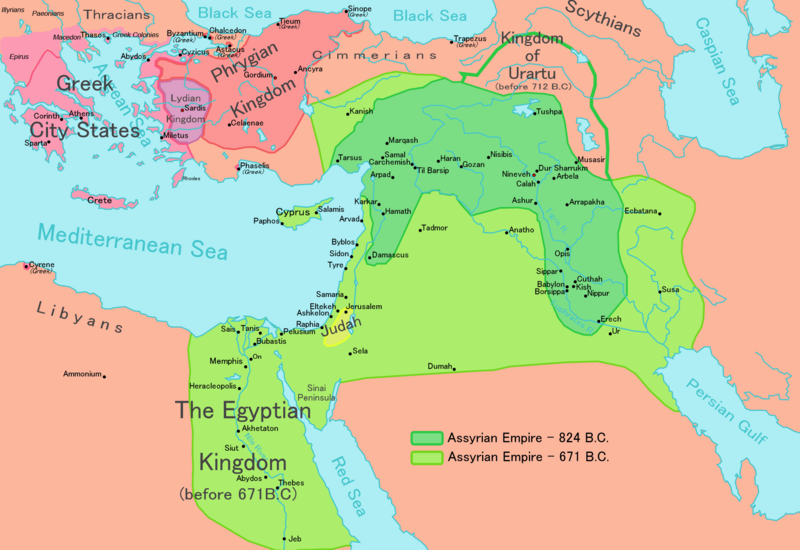

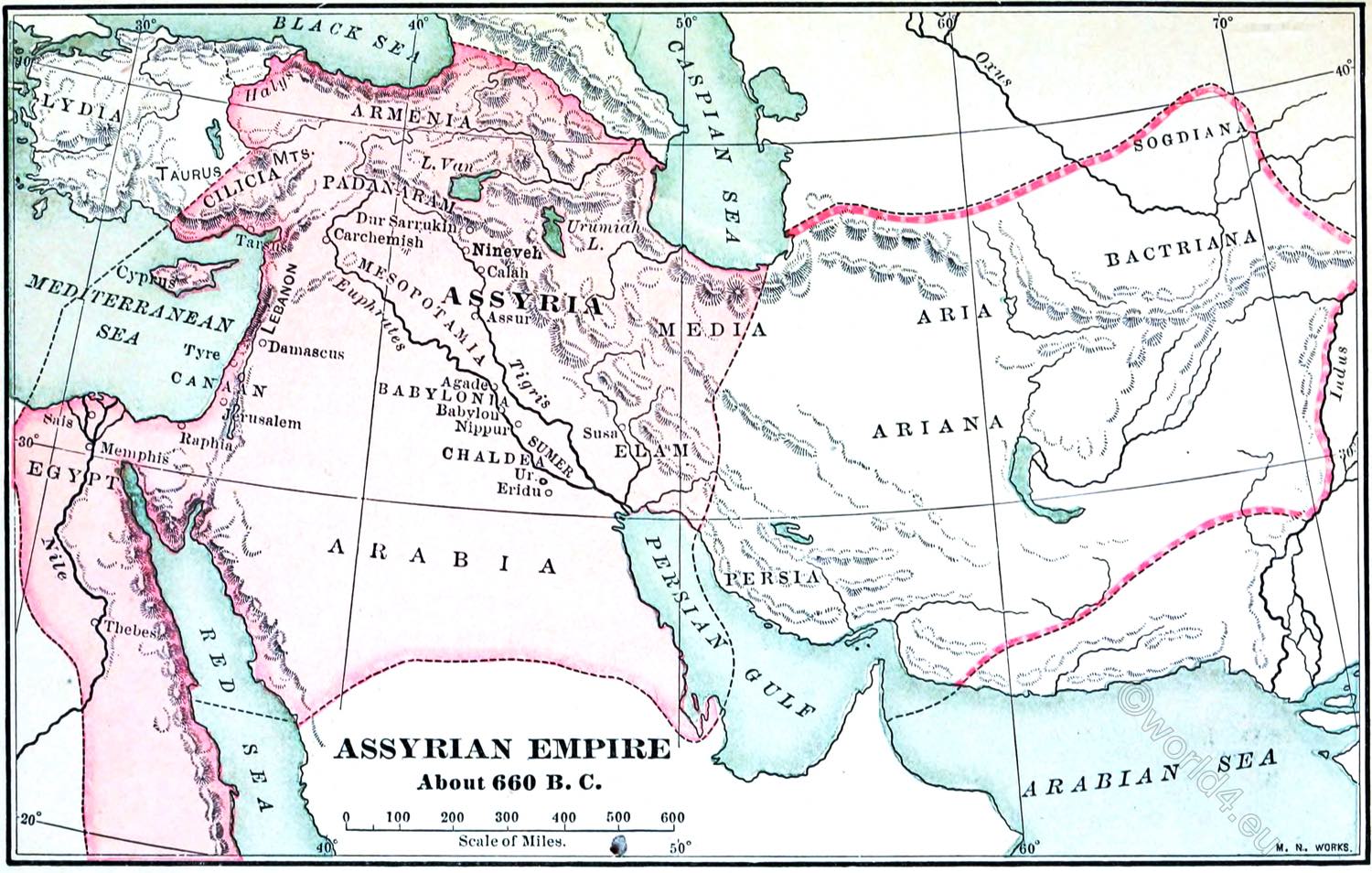

The Assyrian Empire existed about 1300 years, namely from 20 Century BC. until the fall of the capital Nineveh in 612 BC. Nineveh is located on the left bank of the Tigris River opposite the city of Mosul. From research the Assyrian history has been divided into three periods. The old, the middle and the new Assyrian empire. It was towards the end of the 10th Century BC. into a major power in Mesopotamia and surrounding countries through to Egypt.

The new Assyrian Empire (ca. 932-612 BC) is considered the first empire in world history. The language of the Assyrians was a dialect of Akkadian, which was closely related to the Babylonian. As a scripture the Assyrians used the cuneiform writing.

The Assyrian sculpture.

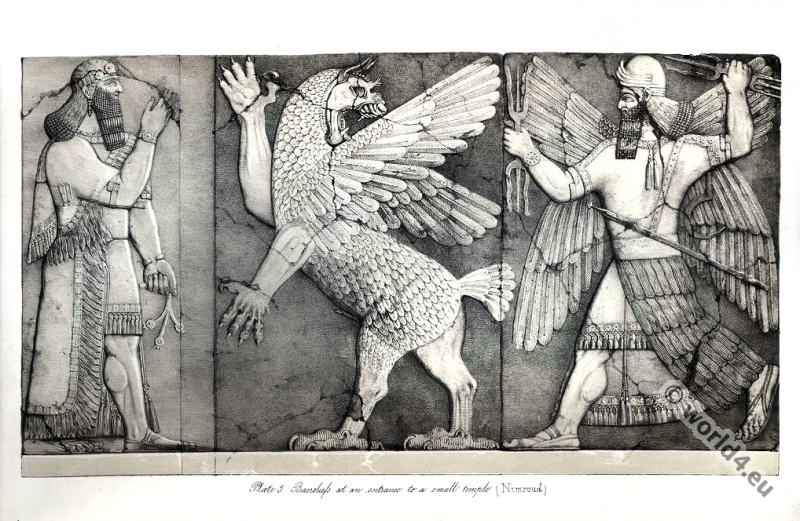

Above

Left: Bas-Reliefs at an Entrance to a small Temple at Nimroud. Part of one side of the entrance near which stood the bas-relief of the King. The group is believed to represent the god to whom the temple was dedicated, driving out the evil spirit. On the opposite side of the doorway the same figures were repeated.

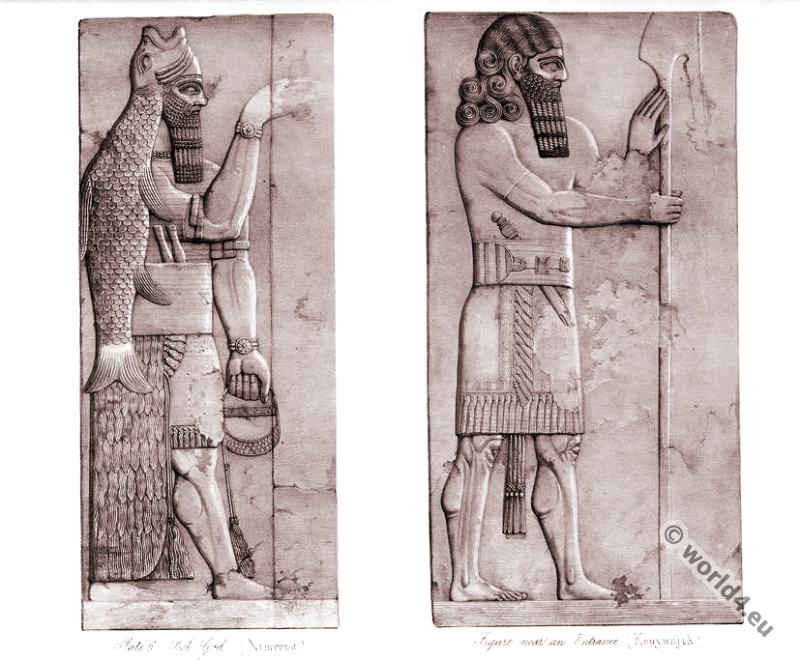

Middle: Fish-God, Nimroud. Supposed to represent the god Dagon of the Philistines. It formed part of the same entrance as the bas-reliefs last described.

Right: Colossal Lion. From an entrance to a small temple at Nimroud. Its length is eight, and height thirteen feet. At the opposite side of the entrance was a similar Lion.

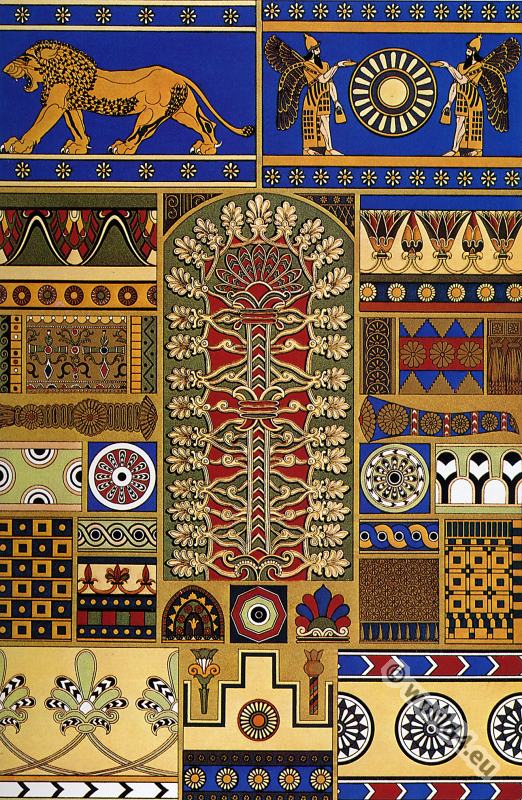

Assyrian and Persian Ornament.

Rich as has been the harvest gathered by Mons. Botta and Mr. Layard from the ruins of Assyrian Palaces, the monuments which they have made known to us do not appear to carry us back to any remote period of Assyrian Art. Like the monuments of Egypt, those hitherto discovered belong to a period of decline, and of a decline much farther removed from a culminating point of perfection. The Assyrian must have either been a borrowed style, or the remains of a more perfect form of art have yet to be discovered. We are strongly inclined to believe that the Assyrian is not an original style, but was borrowed from the Egyptian, modified by the difference of the religion and habits of the Assyrian people.

On comparing the bas-reliefs of Nineveh with those of Egypt we cannot but be struck with the many points of resemblance in the two styles; not only is the same mode of representation adopted, but the objects represented are oftentimes so similar, that it is difficult to believe that the same style could have been arrived at by two people independently of each other.

The mode of representing a river, a tree, a besieged city, a group of prisoners, a battle, a king in his chariot, are almost identical,— the differences which exist are only those which would result from the representation of the habits of two different people; the art appears to us to be the same. Assyrian sculpture seems to be a development of the Egyptian, but, instead of being carried forward, descending the scale of perfection, bearing the same relation to the Egyptian as the Roman does to the Greek.

Egyptian sculpture gradually declined from the time of the Pharaohs to that of the Greeks and Romans; the forms, which were at first flowing and graceful, became coarse -and abrupt; the swelling of the limbs, which was at first rather indicated than expressed, became at last exaggerated; the conventional was abandoned for an imperfect attempt at the natural. In Assyrian sculpture this attempt was carried still farther, and while the general arrangement of the subject and the pose of the single figure were still conventional, an attempt was made to express the muscles of the limbs and the rotundity of the flesh: in all art this is a symptom of decline, Nature should be idealised not copied. Many modern statues differ in the same way from the Venus de Milo, as do the bas-reliefs of the Ptolemies from those of the Pharaohs.

Assyrian Ornament, we think, presents also the same aspect of a borrowed style and one in a state of decline. It is true that, as yet, we are but imperfectly acquainted with it; the portions of the Palaces, which would contain the most ornament, the upper portions of the walls and the ceilings, having been, from the nature of the construction of Assyrian edifices, destroyed.

There can be little doubt, however, that there was as much ornament employed in the Assyrian monuments as in the Egyptian: in both styles there is a total absence of plain surfaces on the walls, which are either covered with subjects or with writing, and, in situations where these would have been inapplicable, pure ornament must have been employed to sustain the general effect. What we possess is gathered from the dresses on the figures of the bas-reliefs, some few fragments of painted bricks, some objects of bronze, and the representations of the sacred trees in the bas-reliefs.

As yet we have had no remains of their constructive ornament, the columns and other means of support, which would have been so decorated, being everywhere destroyed; the constructive ornaments which we have given in Plate XIV., from Persepolis, being evidently of a much later date, and subject to other influences, would be very unsafe guides in any attempt to restore the constructive ornament of the Assyrian Palaces. Assyrian ornament, though not based on the same types as the Egyptian, is represented in the same way. In both styles the ornaments in relief, as well as those painted, are in the nature of diagrams.

There is but little surface – modelling, which was the peculiar invention of the Greeks, who retained it within its true limits, but the Romans carried it to great excess, till at last all breadth of effect was destroyed. The Byzantines returned again to moderate relief, the Arabs reduced the relief still farther, while with the Moors a modelled surface became extremely rare. In the other direction, the Romanesque is distinguished in the same way from the Early Gothic, which is itself much broader in effect than the later Gothic, where the surface at last became so laboured that all repose was destroyed.

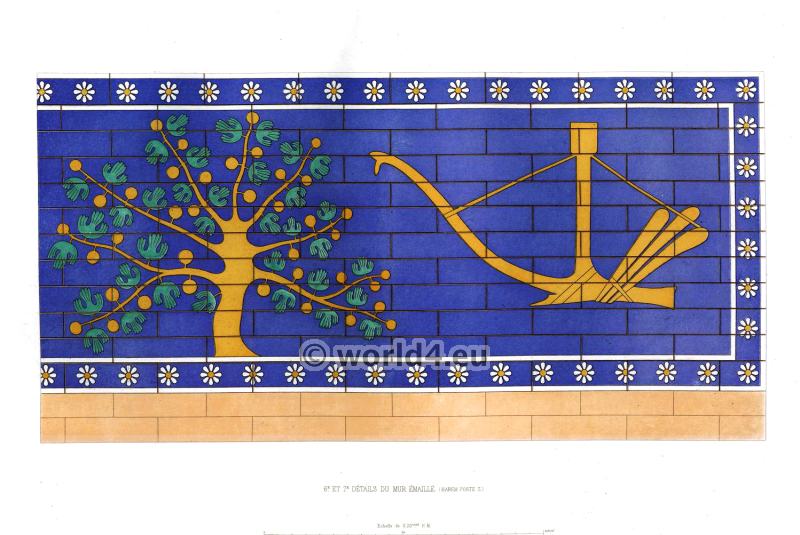

With the exception of the pine-apple on the sacred trees, Plate XII., and in the painted ornaments, and a species of lotus, Nos. 4 and 5, the ornaments do not appear to be formed on any natural type, which still farther strengthens the idea that the Assyrian is not an original style. The natural laws of radiation and tangential curvature, which we find in Egyptian ornament, are equally observed here, but much less truly,—rather, as it were, traditionally than instinctively. Nature is not followed so closely as by the Egyptians, nor so exquisitely conventionalised as by the Greeks. Nos. 2 and 3, Plate XIII., are generally supposed to be the types from which the Greeks derived some of their painted ornaments, but how inferior they are to the Greek in purity of form and in the distribution of the masses!

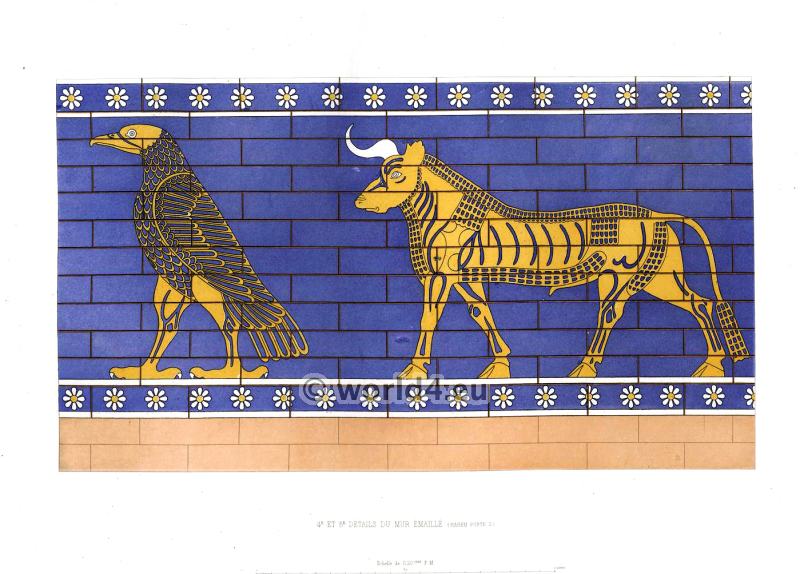

The colours in use by the Assyrians appear to have been blue, red, white, and black, on their painted ornaments; blue, red, and gold on their sculptured ornaments; and green, orange, buff, white, and black, on their enamelled bricks.

Assyrian and Persian Ornament Description

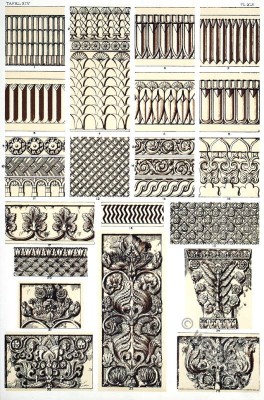

Sassanian capitals

The ornaments, 12 and 16, from Sassanian capitals, Byzantine in their general outline, at Bi Sutoun, contain the germs of all the ornamentation of the Arabs and Moors. It is the earliest example we meet with of lozenge-shaped diapers. The Egyptians and the Assyrians appear to have covered large spaces with patterns formed by geometrical arrangement of lines; but this is the first instance of the repetition of curved lines forming a general pattern enclosing a secondary form. By the principle contained in No. 16 would be generated all those exquisite forms of diaper which covered the domes of the mosques of Cairo and the walls of the Alhambra.

PLATE XII. 1. Sculptured Pavement, Kouyunjik. 2-4. Painted Ornaments from Nimroud. 5. Sculptured Pavement, Kouyunjik. 6-11. Painted Ornaments from Nimroud. 12_14 Sacred Trees from Nimroud. The whole of the ornaments on this Plate are taken from Mr. Layard’s great work, The Monuments of Nineveh. Nos. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, are colored as published in his work. Nos. 1, 5, and the three Sacred Trees, Nos. 12, 13, 14, are in relief, and only in outline. We have treated them here as painted ornaments, supplying the colours in accordance with the principles indicated by those above, of which the colours are known.

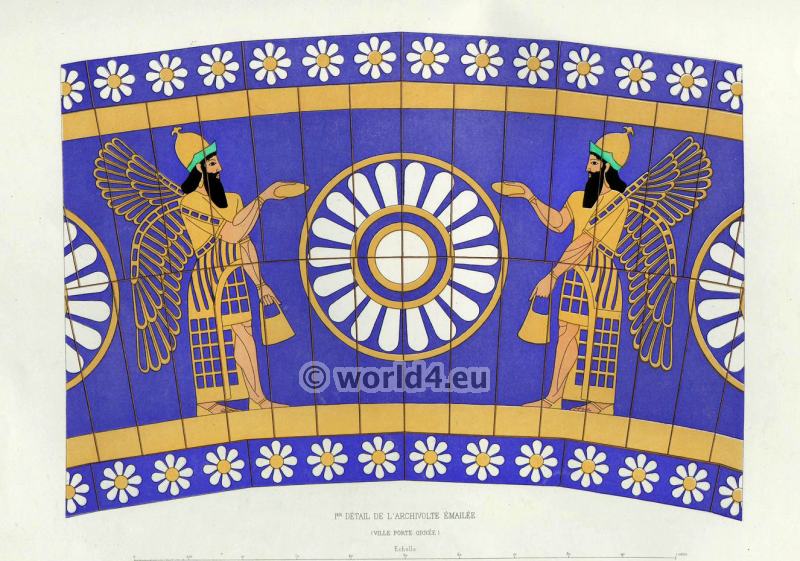

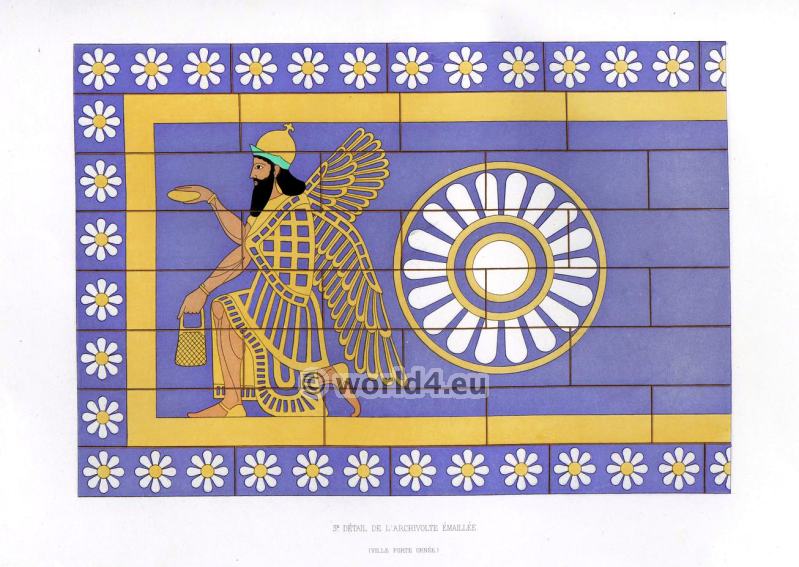

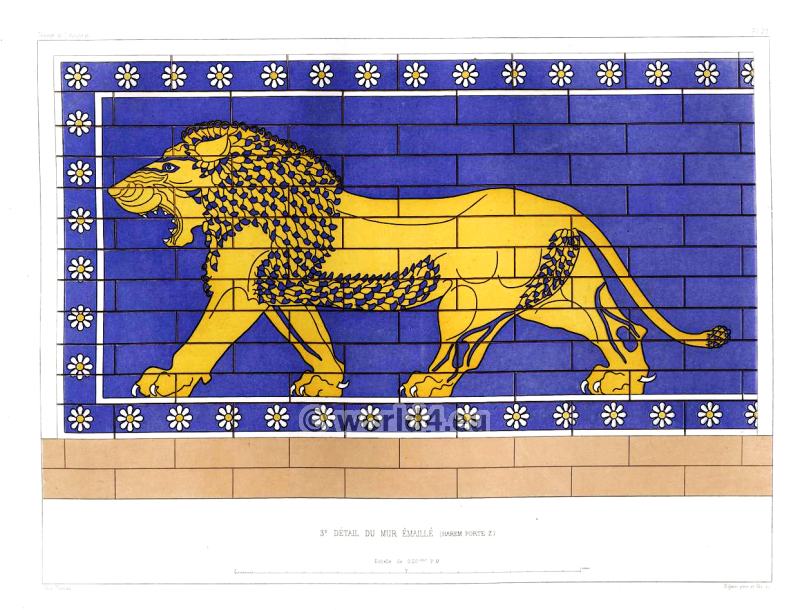

PLATE XIII. 1-4. Enamelled Bricks from Khorsabad. — Flandin & Coste. 5. Ornament on a King’s Dress, from Khorsabad. — F. & C. 6, 7. Ornaments on a Bronze Shield, Ditto. F. & C. 8, 9. Ornaments on a King’s Dress, Ditto. F. & C. 10, 11. Ornaments from a Bronze Vessel, Nimroud. — Layakd. 12. Ornament on a King’s Dress, from Khorsabad.— Flandin & Coste. 13. Enamelled Brick, from Khorsabad. 14. Ornament on a Battering Ram, Khorsabad.—F. & C. 15. Ornament from a Bronze Vessel, Nimroud. — Layard. 16-21. Enamelled Bricks, from Khorsabad. — Flandin & Coste. 22. Enamelled Brick, from Nimroud. — Layard. 23. Ditto, from Bashikhah. — Layard. 24. Ditto, from Khorsabad. Flandin & Coste.

The ornaments Nos. 5, 8, 9, 12, are very common on the royal robes, and represent embroidery. We have restored the colouring in a way which we consider best adapted for developing the various patterns. The remainder of the ornaments on this Plate are coloured as they have been published by Mr. Layard and Messrs. Flandin and Coste.

The ornaments of Persepolis

The ornaments of Persepolis, represented on Plate XIV., appear to be modifications of Roman details. Nos. 3 5 6, 7, 8, are from bases of fluted columns, which evidently betray a Roman influence. The ornaments from Tak I Bostan,— 17, 20, 21, 23, 24—are all constructed on the same principle as Roman ornament, presenting only a similar modification of the modelled surface, such as we find in Byzantine ornament, and which they resemble in a most remarkable manner.

PLATE XIV. 1. Feathered Ornament in the Curvetto of the Cornice, Palace No. 8, Persepolis. 2. Base of Column from Ruin No. 13, Persepolis. 4. Ornament on the Side of the Staircase of Palace No. 2, Persepolis. 5. Base of Column of Colonnade No. 2, Persepolis. 6. Base of Column, Palace No. 2, Persepolis. 7. Base of Column, Portico No. 1, Persepolis. 8. Base of Column at Istakhr. 9-12. From Sassanian Capitals, Bi Sutoun. 13-15. From Sassanian Capitals, at Ispahan. 16. From a Sassanian Moulding, Bi Sutoun. 17. Ornament from Tak I Bostan. 18. 19. Sassanian Ornaments from Ispahan. 20. Archivolt from Tak I Bostan. 21. Upper part of Pilaster, Tak I Bostan. 22. Sassanian Capital, Ispahan. 23. Pilaster, Tak I Bostan. 24. Capital of Pilaster, Tak I Bostan. 25. Sassanian Capital, Ispahan.

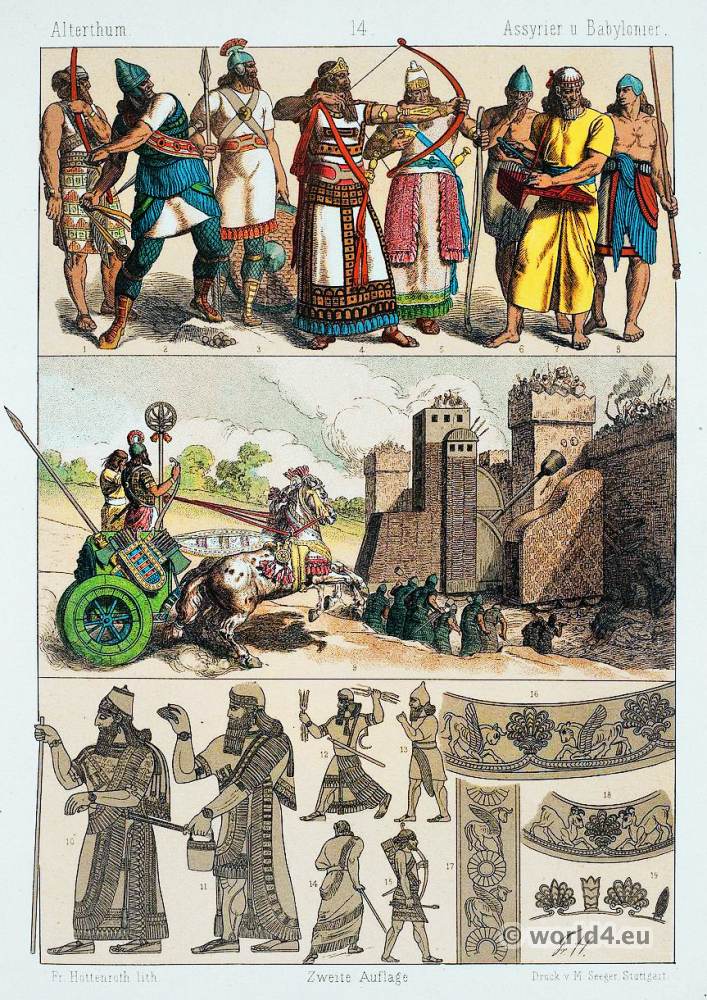

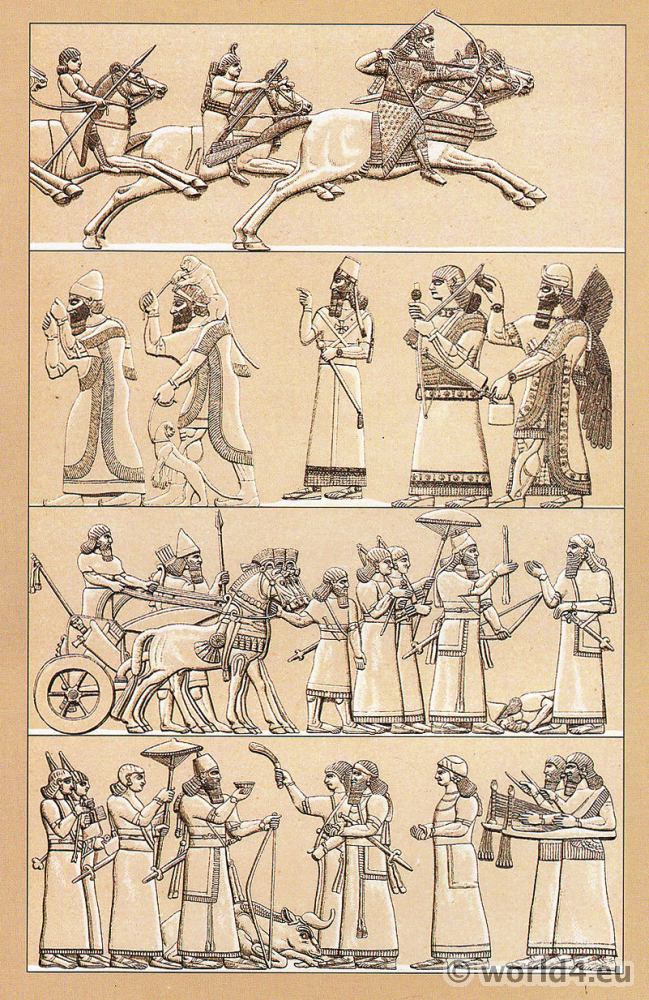

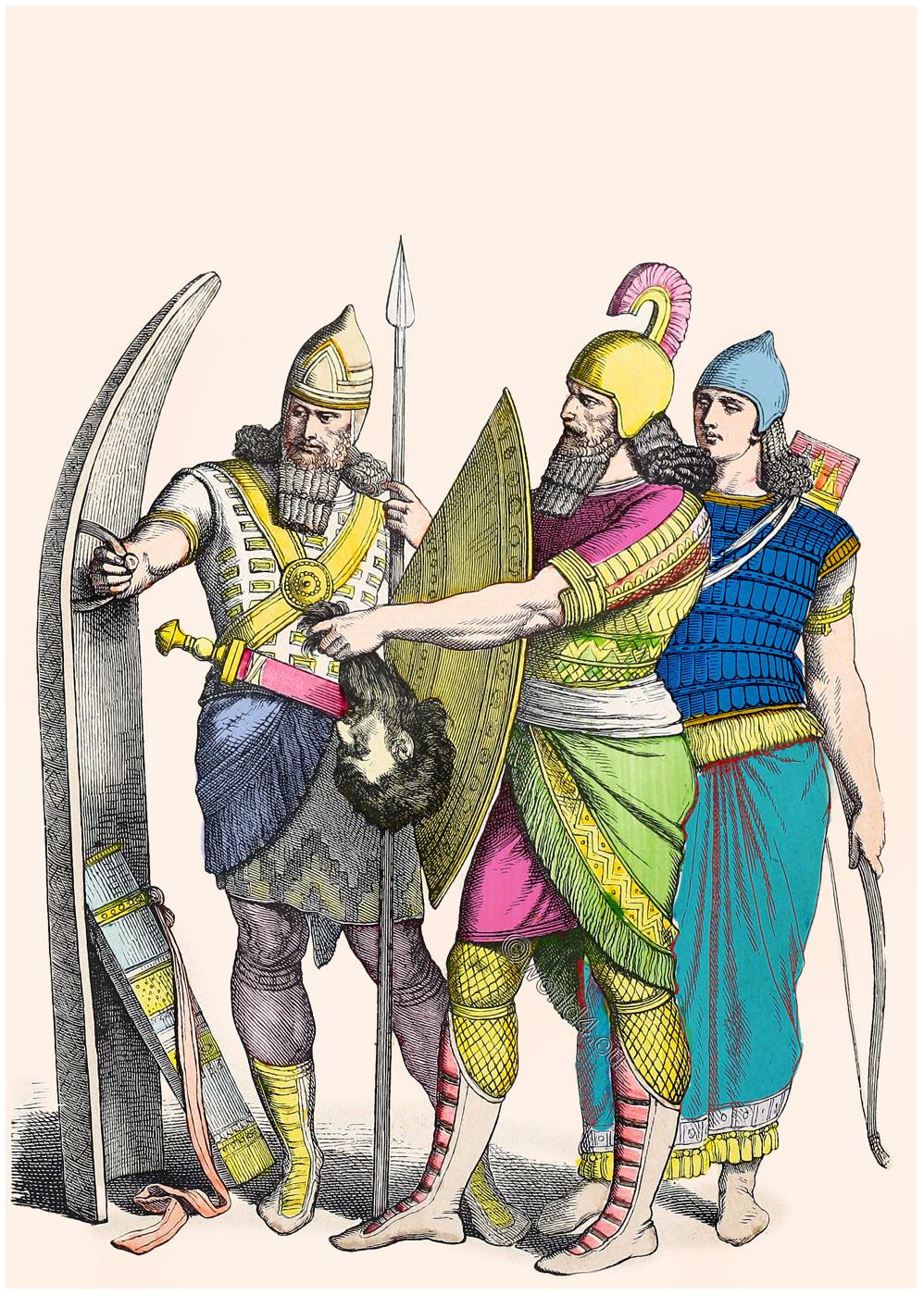

Babylonians and Assyrians Military

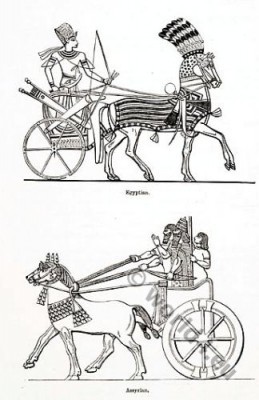

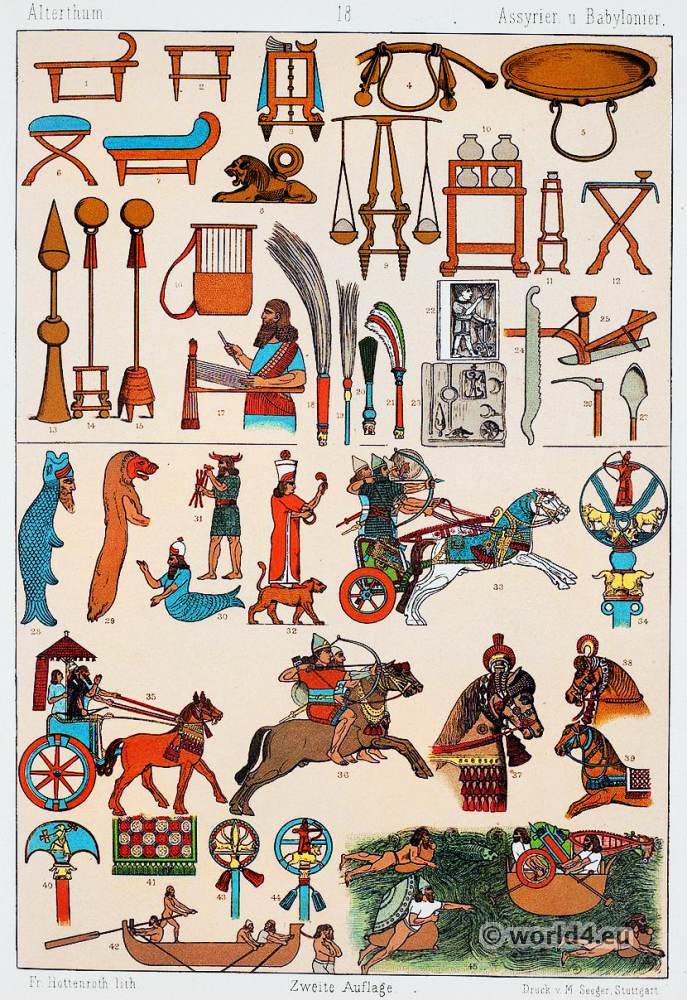

1, 3, 7, 8, light-armed troops; 2, slingers, 4, 5 kings in war and hunting coat, 6, zither player; 9, king in chariots, siege towers and battering rams, 10, 11, 12, 14 reliefs with royal figures, 13, 15, reliefs with figures of ordinary warriors; 16-19 ornaments.

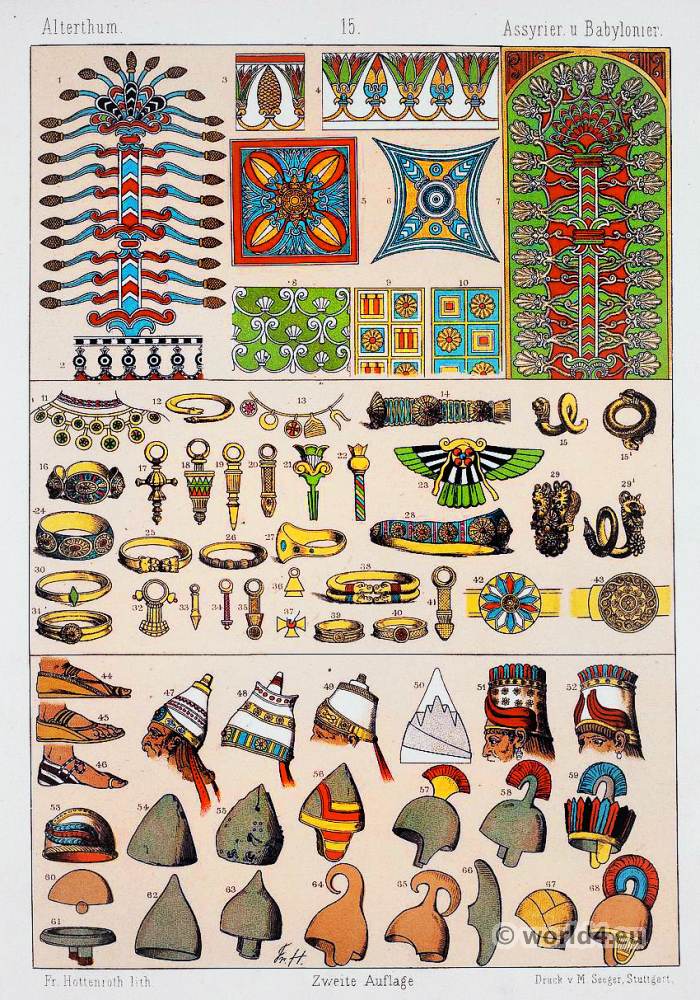

Babylonian and Assyrian Helmets

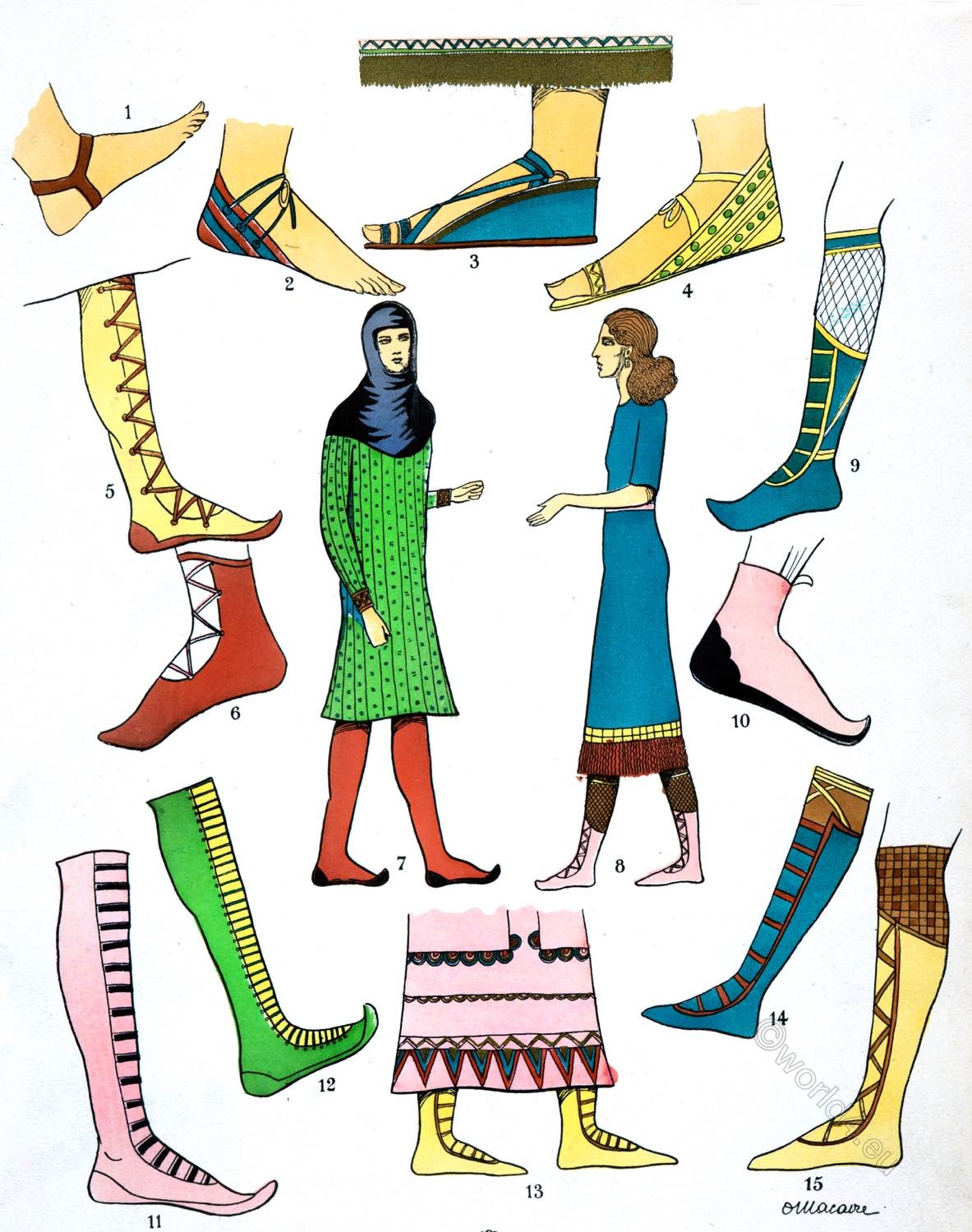

1, 7, so-called sacred tree; 2-6, 8-10 Ornaments (3-5 spruce cones, lotus buds and flowers pattern), 11, 13 necklaces, 12, 16, 24-26, 30, from 31.38 to 40 arm & leg rings, 14, 27, 28 tiaras, 15, 23, 29 symbolic jewelry, 42, 43 belt fittings; 44-46 footwear; 47-53 royal mitres, 54-56, 60, 62 simple helmets made of iron and bronze; 57 , 58 helmets of the foot soldiers, 59, 68, helmets of leaders; 61, frontlet, 63 riders helmet, 64, 65 helmets of archers and auxiliaries; 66 helmet crest; 67 balaclava made of riveted plates.

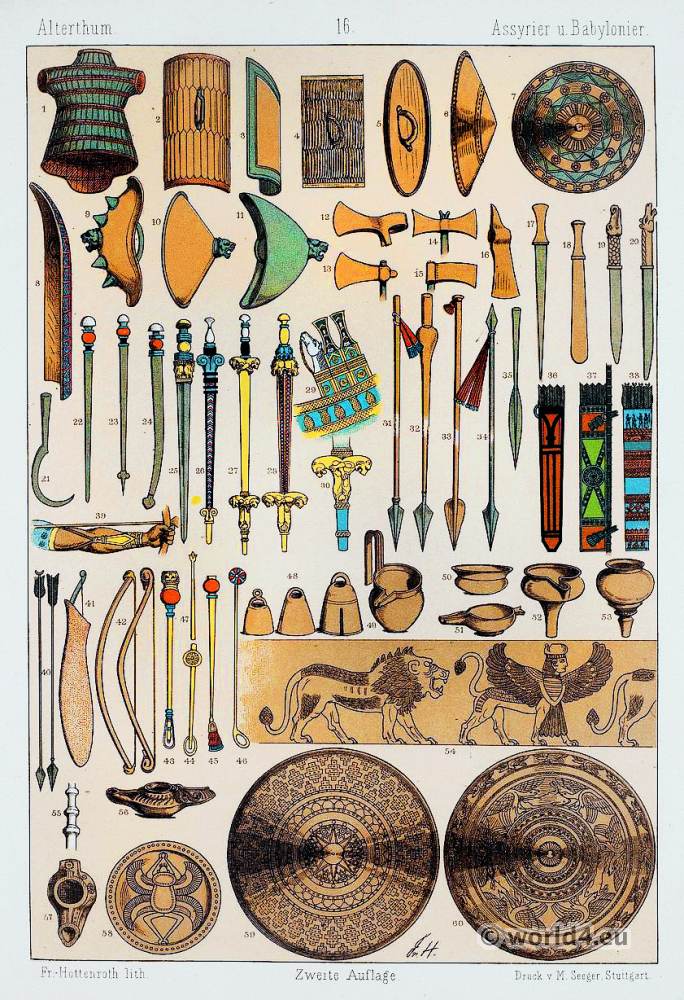

Babylonian and Assyrian Weapons

1 plate armor with rear kilt, 2, 3, 8 gunners shield; 4 braided Hand Shield, 5 flat round shield, 6, 7, 9 -11 deepened round shields with humps, 12, 13, 15, 16 hatchets, 14 double ax; 17-20 daggers; 21 sickle knife, 22 to 28.30 swords and scabbard fittings; 29 dagger handles , 31, 33, 34 darts, 32 shock lance; 35 lance blade, 36-38, 40-42 arrows together with bow and quiver; 39 Arm of a Bogner, 43-47, 55 rod clubs and scepter; 48 bells (or weights), 49 pumping vessel; 50 cup, 51, 56, 57 lights, 52, 53 funnels, 54, 58-60 boiler plates and ornaments.

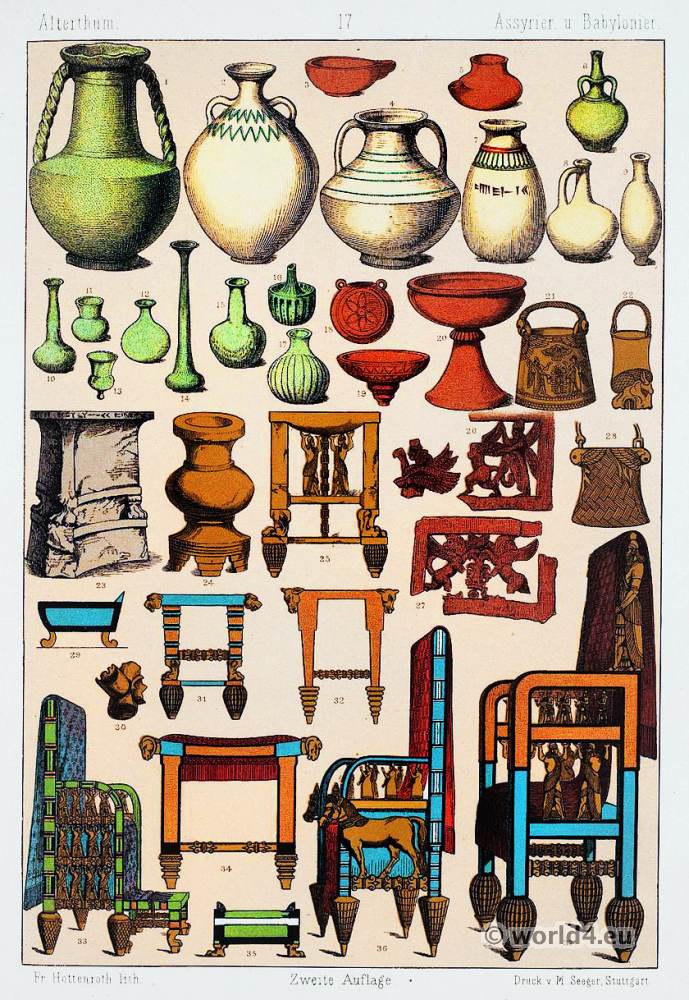

Babylonian and Assyrian Pottery and Furnitures.

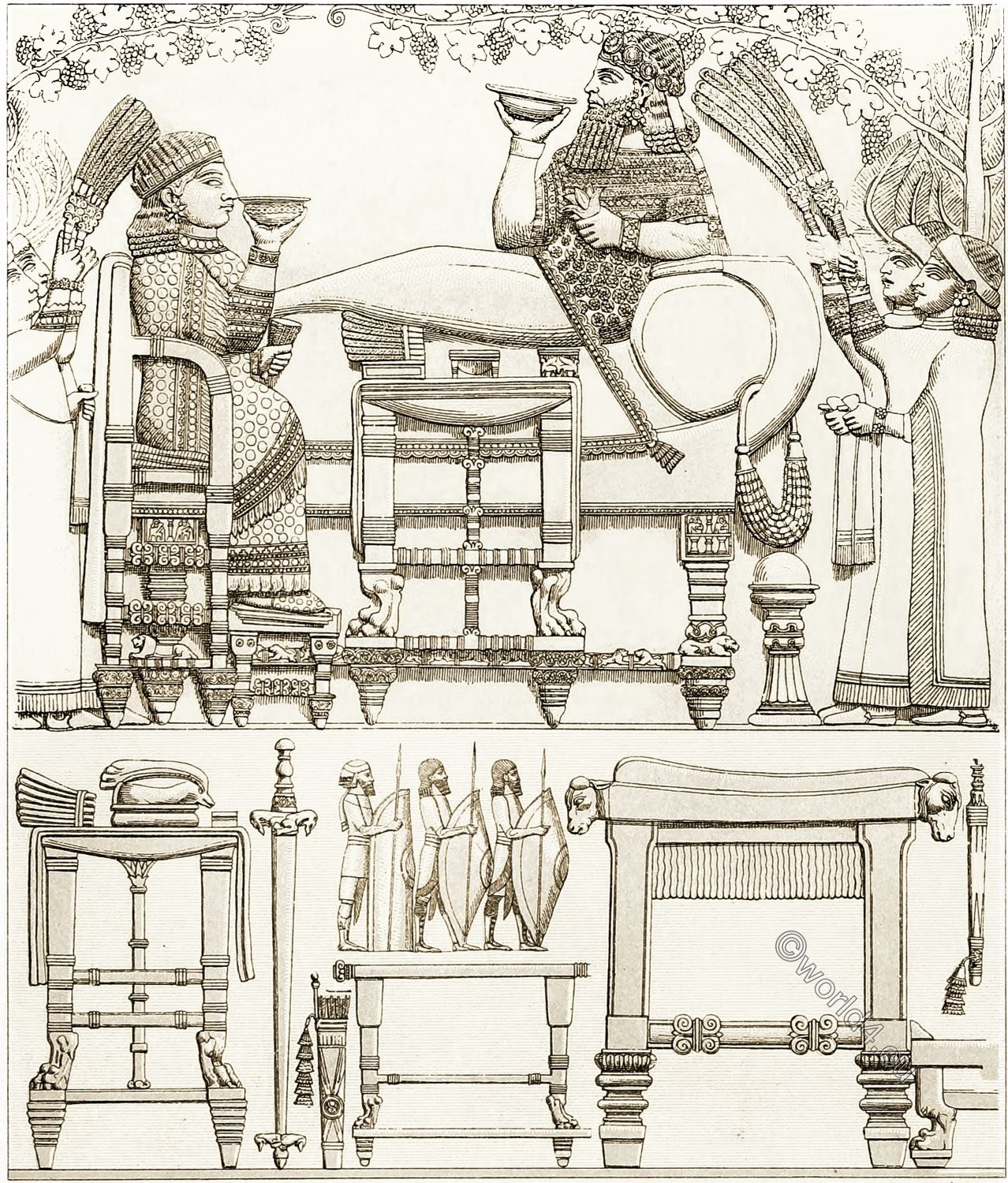

1-9 pottery; 10 -17 glass vessels, 21, 22, 28 Temple vessels; 23-25 altars, 26, 27, 30 parts of throne chairs, 29, 35 stool, 31, 32, 34 seats, 33, 36, 37 throne chairs.

Babylonian and Assyrian Economy.

1, 7 deposits, 2, 3 tables with pedestal; 4,5 tabletops (?); 6 folding chair; 8 Weight (?); 9 scale on pedestals, 10, 11 sideboard tables, 12 table; 13-15 Fire and Incense stand before the altars; 16, 17 harps; 18-21 fronds; 22 carving in ivory, 23 mold for jewelry, 24 Drumm saw; 25 Plough; 26 hoe, 27 bucket, 28, 29 priestly masks; 30-32 idols; 33 chariots with manning, 34, 40, 43, 44 ensigns, 35 King on the war chariot; 36 archers on horseback; 37-39 horse stuff; 41 saddle blanket, 42 barge; 45 warrior on tubes floating boat with chariots.

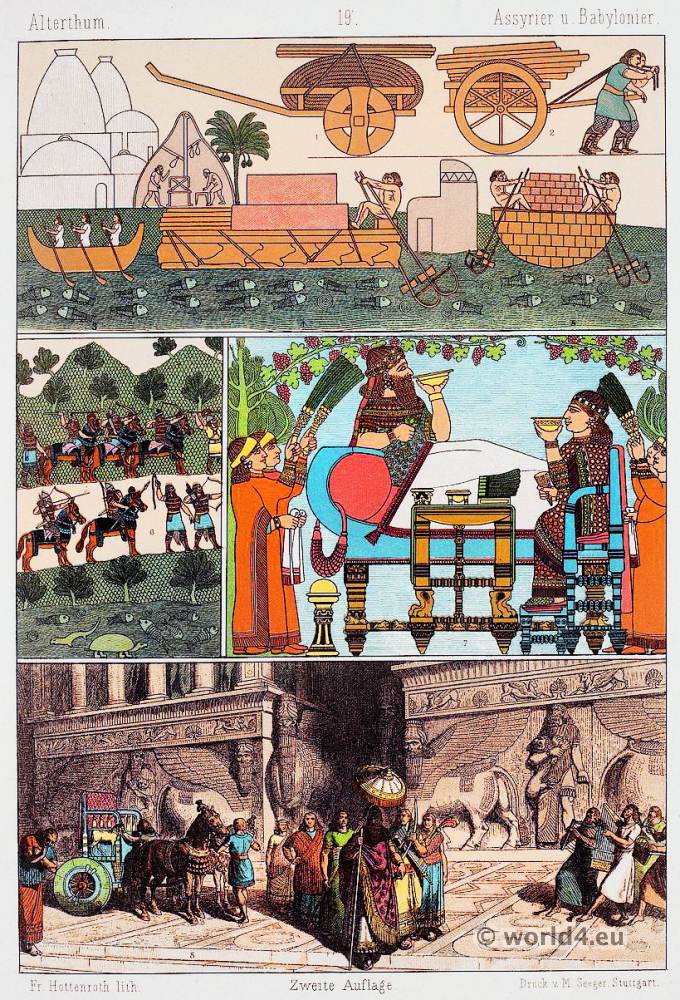

Babylonian and Assyrian Ceremonial and War.

1, 2 cargo carts with carters, 3, 5 barges, at the back of the building and a tent; 4 raft of beams and air-filled tubes; 6 landscape, archers on horseback and on foot, commander; 7 king and queen at the feast, servants; 8 portal of a royal castle, mobile throne chair. Assyrian King with his entourage, minstrels.

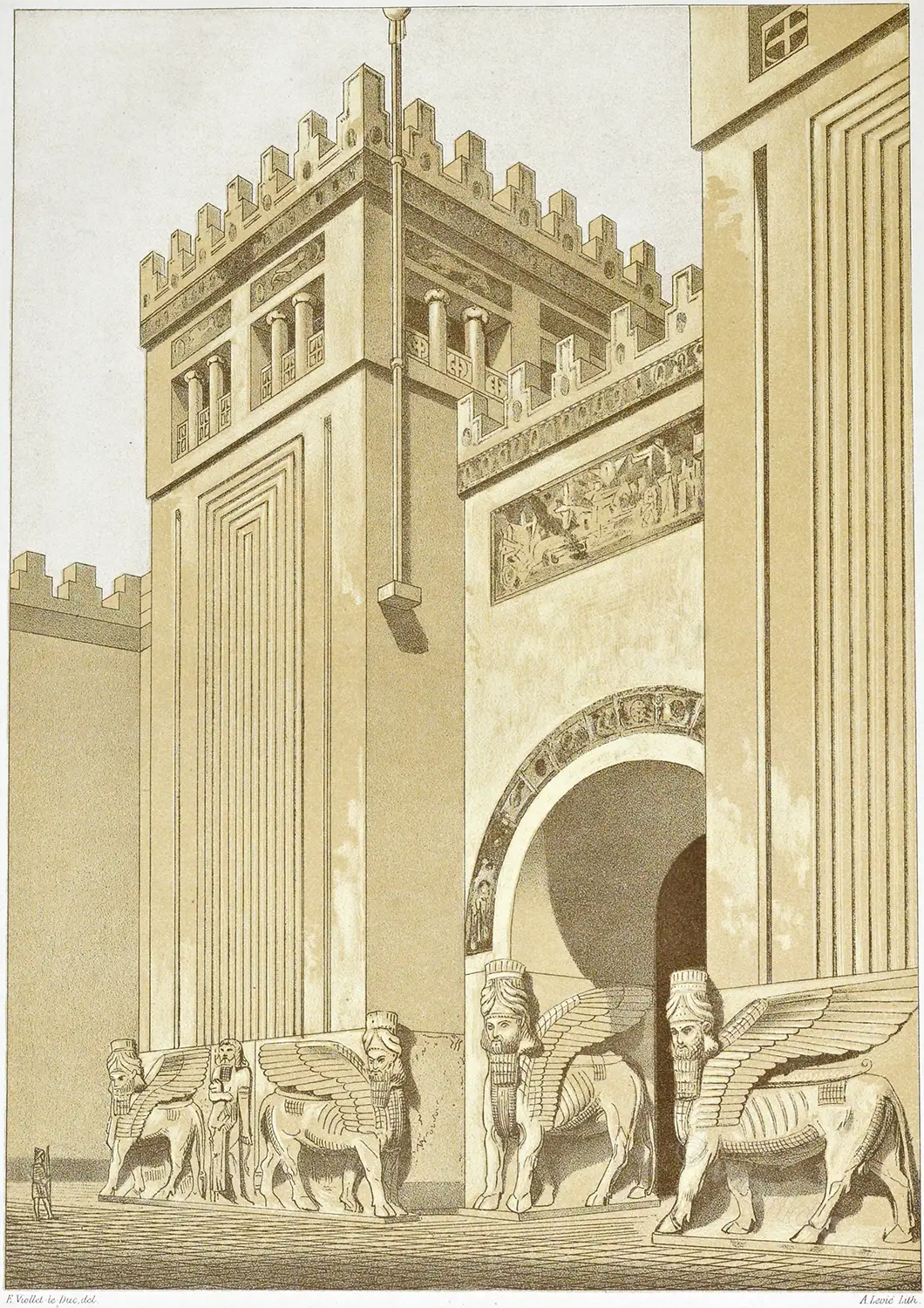

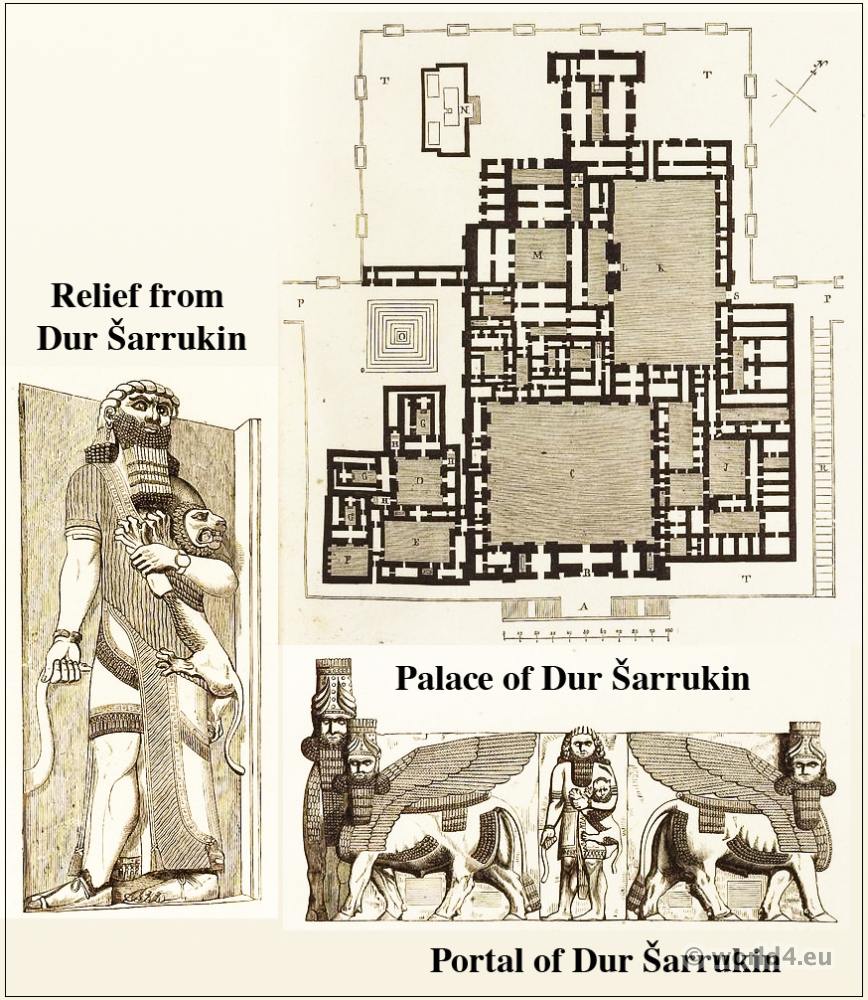

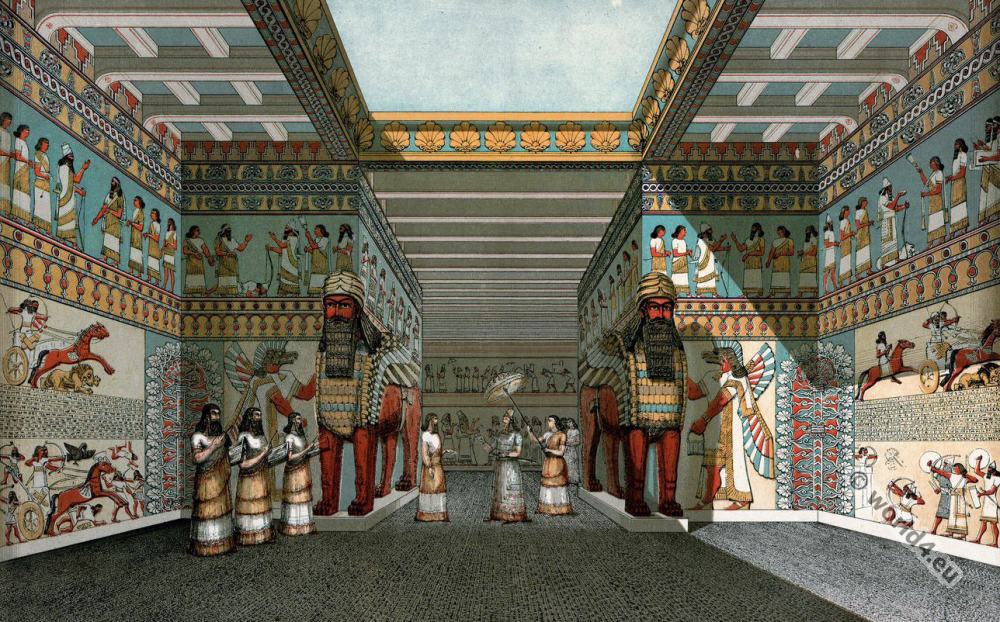

The Palace of Chorsabad, Dur Šarrukin.

T. – Terraces system with wall and towers; 314 meters wide, 344 meters long. P.P. Sequel to the enclosure wall to the city. A. Staircase. B Main portal. C. Main Courtyard of the front building. D-H. Women’s quarters (Harem) J. Middle courtyard of farm buildings. K. Main courtyard of the royal apartment. L. Portal with bull figures as gatekeepers (see picture below). M. Central courtyard of the royal apartment. N. Temple 8?). O. Step pyramid (base area about 43 feet square, with four levels, each with about 6 meters height). R. Entrance for wagon and rider.

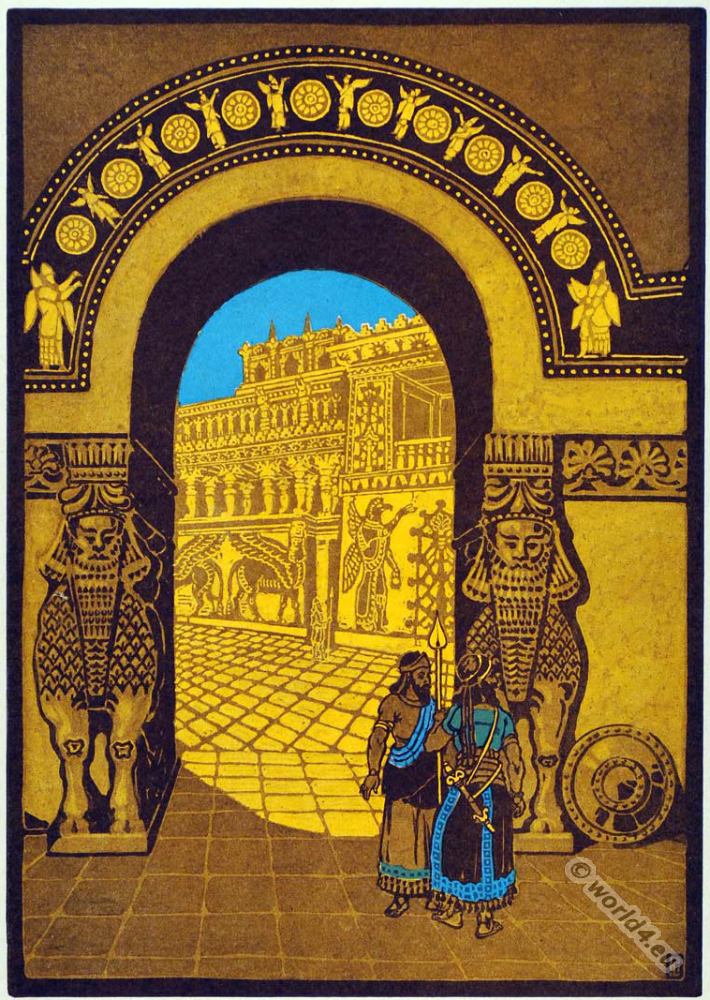

Above: Relief and Portal from Chorsabad. Palace of Chorsabad. Built by King Sargon in 710 BC. The palace was the largest ever created residence of the Orient. The residence was not a city in the conventional sense, but rather a citadel, was nearly square created (1760 m to 1635 m) and covers an area of 3 km ². Dur Sharrukin was surrounded by a massive wall with 183 towers and seven gates.

Related

Links:

- HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION: ASSYRIA. The Oriental Institute.

- Silvia Schroer: Gender and Iconography from the Viewpoint of a Feminist Biblical Scholar (PDF)

- The British Museum : Assyrian sculpture and Balawat Gates.

- Pergamonmuseum Berlin

- Department of Near Eastern Antiquities, Louvre Paris.

- Near Eastern Antiquities in the Louvre – Room 4

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.