German costume history. Middle ages.

Women fashion of the 15th century.

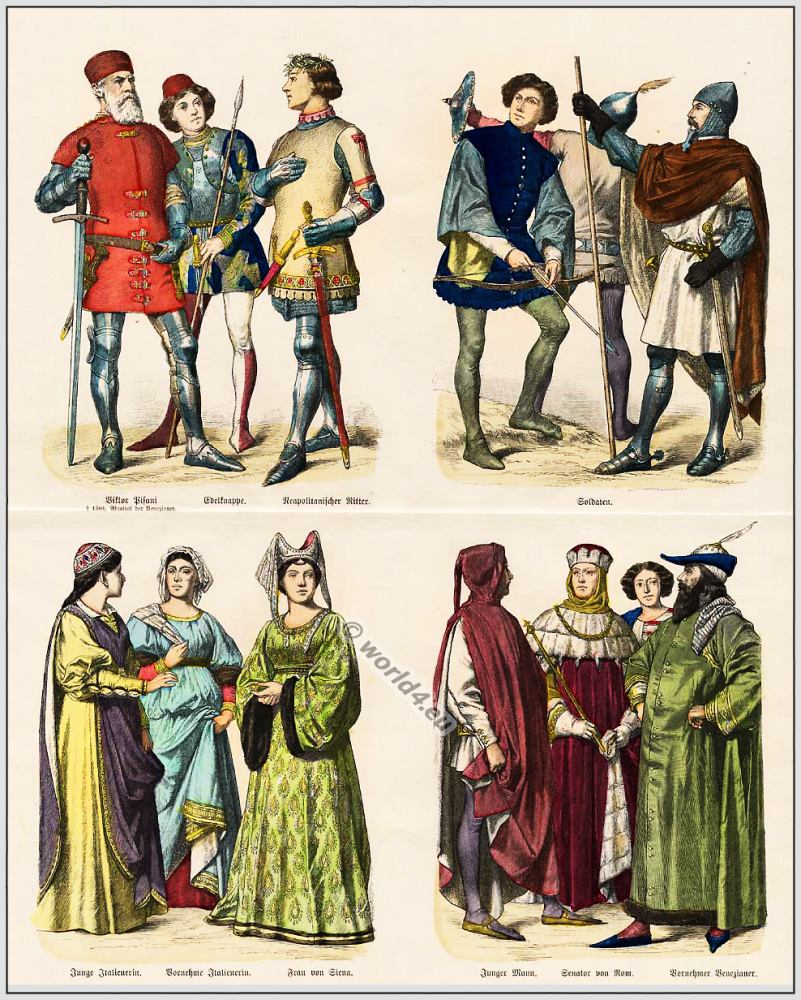

The fashions that prevailed at the end of the 14th century were still in vogue at the beginning of the 15th. The bodices were still as close-fitting as ever, and long sleeves were still the rule. The extravagantly expensive materials and trimmings, including points and bells, called forth various prohibitions from the ruling powers, but these were all in vain. Women as well as men trimmed their clothes with long peaks and points. Waist-belts, necks, and the points of the peaks were hung with little bells.

The under-dress continued without much change during nearly the whole of the fifteenth century. It fitted closely from the shoulders to below the hips, and was widened from that point downward by the insertion of gussets on both sides. It was made to fit still more closely by being laced in front (Fig. 229). It came only a little higher than the shoulders, and was very wide at the top, being cut in a very low V-shape at the back and in front.

The sleeves were tight, and came down to the hands. Short sleeves were worn only when the over-dress had long, very tight sleeves. The under-dress was the usual indoor wear, and was long enough to hide the feet. Some parts of this dress, especially the sleeves and the band round the foot, which were not covered by the over-dress, were made of the best and finest material available. If only a cloak was worn over it, the under-dress was fitted with sleeves like those of an over-dress both in shape and length (Fig. 230).

The over-dress was like the under-dress, except that it was laced at the back. It was very long (and became longer about the middle of the century), and was low-necked, although at the beginning of the century the neck had been high. The width varied. Like the underdress, it sometimes fitted very closely from the shoulders to below the hips; sometimes the widening began at the bust. In the latter case the waist-belt came close up to the breast. The greatest change was in the sleeves. These were mostly long and pendent, but sack sleeves and long, open, wing-shaped sleeves with or without points were also fashionable. These points appeared not only at the edges, but also along the sleeve-seam.

The shape of women’s sleeves was similar to that of the sleeves of men’s coats. The cloak still served as a gown for special occasions. It was worn then, however, only by women of the upper classes (Fig. 230), who were distinguished by the simple cut and tasteful color of their clothing from the middle classes, who were still fond of garish dress. The cloak was still the long-established semicircular one, and was still fastened with one clasp. The cloak for great occasions, however, was sector-shaped, and was fastened with clasps on both shoulders.

During the first half of the fifteenth century various cap-shaped forms of headdress were worn by women, both married and unmarried, but women of the upper classes wore nothing but the coif (Haube, Hulle, Kruseler), trimmed with several close rows of ribbon (Figs. 230 and 232). Over the back of this Haube was drawn, as in the fourteenth century, a white Gugel (hood), the lower edge of which was also trimmed with several close rows of ribbon. Frequently, also, women wore over this a long kerchief, of no great breadth, which was folded in two longitudinally and then rolled loosely and bunched into cap-shape.

This kerchief was in most cases white. The long ends were allowed to fall down behind. The ordinary footwear consisted of low shoes with long, pointed toes.

Most of the attire described above underwent a complete change during the second half of the fifteenth century. Dresses became lower and lower at the neck and trains became longer. At the same time the preference for mi-parti and for points and bells as trimming went so far that the authorities did all they could to discourage the use of rich material, expensive trimming, and extravagant ornamentation.

While the under-dress remained as it was, the changes in the over-dress were extensive. The fashion now was to have the dress close-fitting to below the bust, even without a waist-belt, and as wide as possible from that point down. Nearly all the changes that were made in it were intended to achieve this end.

With that purpose in view the over-dress, which was open at the back to below the shoulder-blades, and arranged for lacing, was now made close fitting to below the breast, then quickly widening downward. The waist-belt was first put on low down; later waist-belt and dress were pulled up so that a loose mass of folds was made at breast-height all round (Fig. 233). Dresses that were tight all the way down to below the hips were widened in another way. A strip was cut out of the front of the dress from the foot up to below the breast, then replaced by a much wider one (see Figs. 234-236). Before it was sewn in the top of this wider strip was folded or pleated so that it fitted exactly into the place of the excised strip; then its upper edge was sewn in with a double seam.

The folds of the inserted strip were stitched to a distance of 14 cm. or a little more from the top, and then allowed to fall loose. Finally the sides of the whole strip were sewn in. The dress was thus made much wider below, but close-fitting from the top to the point where the folds were stitched. These folds or pleats were frequently padded. If still more width were desired additional gussets were inserted at the sides and at the back. These reached up to the hips. Dresses of this kind were usually open at the back down to the hips, and were fastened by lacing.

The most important improvement in women’s dress, however, took place at the end of the fifteenth century. The bodice was then divided entirely from the skirt. The two were cut separately, and then sewn together by a double seam. The tailor was now able to make the dress of any desired shape, to make the bodice long or short, loose or tight, and to pleat the skirt in any way that was desired. This improvement brought with it a far greater variety of cut, but it was a considerable time before the new style was universally adopted.

The greatest possible variety characterized the shape and width of the neck and the sleeves in women’s attire during the second half of the fifteenth century.

The neck was as low as possible; various styles were current. The shoulders were sometimes completely exposed, or if they were covered, most of the back and breast was bare. In the latter case women covered the bust with a dainty wimple embroidered with gold. A chronicler of the day describes this fashion thus: ” Girls and women wore beautiful wimples, with a broad hem in front, embroidered with silk, pearls, or tinsel, and their underclothing had pouches into which they put their breasts. Nothing like it had ever been seen before.”

At the same period, however, some dresses were by no means so low-cut. Some of them were quite high at the neck, and some even had fairly high collars.

Similar variety was seen in the width of women’s dresses. Many types were in fashion. Some women wore waist-belts, while at hers dispensed with their use. The favorite style was a dress that fitted closely from the neck to the hips. As a rule dresses were immoderately long, and ladies of the upper classes frequently wore trains (Schleppen, or Schweifen) so long that they had to be carried. Toward the close of the fifteenth century women began to wear very long, wide dresses, with long, wide sleeves. These fitted closely only over the breast and shoulders, hanging loose all round from the waist down. These dresses, which were cut like wide tunics, were made still fuller by the insertion of gussets.

Some of them were closed all round; others were open all down the front. In the former case the drosses were very low across tie shoulders. The front was gathered at the bust in several large pleats and fastened with a clasp (Fig. 238). In the other style, although it was quite open in front, the dress was very close-fitting to below the breast; this was achieved by gathering the material into a clasp (Fig. 239). This not only fastened the front parts of the dress together, but also raised them a little.

Toward the middle of the century the long, pendent sack sleeves went quite out of fashion, except those with the hand-opening near the wrist. More popular than these, however, were the long, open, hanging sleeves called Flügel (wings). Frequently so long that they trailed on the ground, they were splendidly finished with fur and points. Near the end of the century appeared sleeves that extended beyond the hand. They were rather tight at the top, but so wide lower down that the width at the foot was nearly equal to their length. At the same period slashed sleeves came more and more into favor. Some were slashed the whole length at the back, and tied with cords drawn not quite taut over the dainty, puffed white under-sleeves. Some sleeves were so long that they extended beyond the hands and had to be turned back when the hands were to be used.

All these sleeves were cut straight, and, except the very wide ones, had only one seam. According to taste this seam ran in front or at the back, or even under the sleeve. The sleeve-hole was usually as small as possible, and shaped either like an egg with the small end up or like an upright oval. The sleeves of the under-dress, which were visible through the open sleeves of the over-dress, were now wide, now tight; in some cases they were so long that they came beyond the hands and in others so short that they hardly reached the middle of the forearm. Now that wide over-dresses were fashionable the cloak was used only for protection in rough weather. It was either semicircular or shaped like a sector or like an arc, and was gathered into numerous close pleats. It had a broad, smooth, turn-over collar, sometimes stiffened, and was usually more than knee-length. Only married women wore it.

Girls did not wear it till they became brides. The cloak still continued to be worn at the various royal Courts as the dress for occasions of great ceremony. It was shaped like a sector of a circle, covered only the back, and was held in position by a braided strap that passed across the breast. This cloak had a train, and its length was in proportion to the rank of the wearer. The Tappert continued to be worn till about the year 1480, but it was mostly used as an over-coat, and therefore always had a hood. The most popular type of it was open down both sides.

During the second half of the fifteenth century the headdress exhibited great diversity of appearance. There were hair-nets made of gold thread, in which the hair was so disposed that it formed large pendent masses at both sides of the face. Over these nets women wore kerchiefs with points at the ends, or cowl-like coifs, also with points. There were also other forms of headdress which did not cover the hair. The hair was then worn in plaits, which either hung down the back or were arranged in various ways round the head.

Other women wore circular rolls or pads covered with ribbon or cloth (see Plate III), as well as various kinds of caps, circlets, bandeaus, etc. Ruffled caps (Kruseler) had been out of fashion since the middle of the century. Footwear took the form of pointed shoes. Ladies wore them of such length that special soles had to be attached to keep the long points in position. At the close of the century even women’s shoes were much shorter, and the fashion of long, pointed toes ultimately disappeared.

Gloves of silk material or of soft leather were at first worn only by ladies of high standing. The fashion quickly spread, however, and by the end of the century gloves were looked upon as indispensable by prosperous middle-class people.

Source: A History of costume by Carl Köhler. Edited and augmented by Emma von Sichart. Translated by Alexander k. Dallas M.A. Lecturer in German In Heriot-Watt College Edinburgh.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.