Hamarikyū Park (浜離宮恩賜庭園, Hama-rikyū onshi teien, Japanese for “Imperial Garden of the Hama Residence”) is a park in the Chūō district of Tokyo, Japan. The park with its ponds and teahouses is an important example of Edo period culture, despite the destruction of many individual buildings.

THE HAMA RIKIU GARDEN AT TOKYO

by Josiah Conder.

This is another of the Imperial gardens of the capital taken over from the Shogunate at the time of the Restoration. It occupies a site which, until the middle of the seventeenth century, was merely a marshy level, fifty acres in area, overgrown with reeds and rushes, and used as a hawking ground by the Shogun. Iyetsuna presented the land to one of his relatives, who converted it into a garden, and furnished it with suitable buildings.

It became an occasional summer resort for the Regent and his Court, its position, on the shore of Tokio Bay, rendering it a cool and refreshing retreat, and obtaining for it the name of Hama Goten, or the Palace on the Coast. Records dating from the year 1708 mention the following garden structures: “Island Tea-house,” “Ocean Tea-house,” “Bubbling-spring Tea- house,” “Shrine of Kwannon,” “Shrine of Koshin,” *) and “Bridge of the Front Gate.”

*) Kwannon and Koshin are both popular deities, shrines dedicated to whom exist all over Japan.

An extensive conflagration in the year 1725 destroyed the buildings and damaged the grounds, which were remodelled under the Shogun Iyenari, at the end of the eighteenth century. The principal detached pavilions then erected were: the “Swallow Tea- house,” “Pine-tree Tea-house,” “Thatched Tea-house,” “Pine-grove Arbour,” “Hut of the Salt-coast,” “Arbour of the Royal Mountain,” “Arbour of the Fifth Moat,” and “Azuma Arbour” — Azuma being an ancient name for Japan. Just before the Restoration, in 1867, the estate passed into the hands of the Ministry of Marine, and in the following year was transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and used for entertaining foreign visitors of distinction. Eventually the Imperial Household Department took possession of the site, when the name was slightly changed to Hama Rikiu, or Detached Palace of the Coast, the term Rikiu being applied to all the secondary palaces or Imperial villas. Meanwhile, the garden had become much out of repair, only a few of the ornamental arbours remaining.

An old book, published in 1843 by Oyamada Yosei-O, a retainer of Prince Kwacho, gives the following account of the chief attractions of these grounds:—An elevated hillock called the “Mountain of Eight Views” afforded an extensive prospect of the sea and distant hills. Near its base was a small lagoon containing irises and other water-plants. “Ocean View Hill” was the name of another eminence over- looking the Bay planted with mountain grasses and pine trees. In the western quarter of the garden, and providing an uninterrupted prospect of Fujisan, was another hill called “Fuji-viewing Hill.” Close to a rocky mound, covered with azalea bushes, was a beach arranged with artificial salt-making beds and kilns, designed in imitation of the primitive salt factories abounding on the Japanese coast. A few peasants’ huts embowered in high grasses and wild flowers, and a picturesque cottage, called the “Sea-shore Tea-house,”—from which a sea view, including the cliffs of the opposite coast could be enjoyed,—imparted a charming rural character to this spot.

Another feature of the garden was the “Embroidery Hall,” a detached building used for the manufacture of the beautiful Aya-nishiki, the working of which was formerly a favourite pastime of the Court ladies. A grove of pine trees, in which was buried a little arbour called the “Pine-grove Tea-house,” lined the approach to this hall. The “Thatched-hut Tea-house,” already mentioned, was constructed to resemble the hostelry of a country road, fitted up with the simple implements and furniture peculiar to country life. It is said to have been used by the Shogun as a hunting-box for hawking. A miniature structure, built in delicate taste, and called the “Swallow-Tea-house,” was furnished with several valuable Chinese pictures and other antique treasures of the So period. At the side of a winding pathway leading to the garden lake was a pretty bower, called the “Trellised Arbour,” overlooking a large bed of chrysanthemums.

Other buildings referred to were: the “Orchid House,” containing Chinese orchids and other rare plants arranged in flower-pots; a closed summer-house called Azuma-Ya; and a little fane to Azuma Inari, the Fox God, half hidden in a small plantation of trees suggestive of a temple grove. A hill, called Reiisan, gave a good prospect of the neighbouring garden of the Shiba Rikiu, to the south-west. It was rocky and precipitous on one side and adorned with crooked, overhanging pine trees, in imitation of the wild scenery of the Japanese coast. From still another eminence, more than twenty feet in height, and named Kembanzan, the large trees of the distant Fukiage Garden could be seen. The cascade at the head of the lake, the water for which was brought from the river Tamagawa, was picturesquely designed. A striking feature of this garden is a long winding bridge crossing the lake, covered in parts with wistaria trellises, which are loaded with immense racenes of purple flowers in the season. The Hama Rikiu is now chiefly known for its unrivalled show of double cherry blossoms in spring, forming an attraction honoured yearly by an Imperial visit and reception.

HAMA RIKIU GARDEN

Supplement to Landscape gardening in Japan by Josiah Conder

The Imperial garden parties held in the Spring, for viewing the cherry blossoms, have rendered this garden familiar to most residents and visitors. Prior to the Restoration, the site was occupied by the summer palace of the Shogun, called the Hama-goten, or “Palace of the Coast,” and it formed a favourite resort during the hot season, situated on the shore of the Tokio Bay.

The garden was designed with considerable imagination and skill to suggest famous views in Japan, such as, Matsushima; the Eight view’s of Omi; and different coast scenery. “Swallow Tea- house,” “Pine-tree Tea-house,” “Thatched Tea-house,” “Hut of the Salt-coast,” “Ocean View Hill,” “Fujisan-viewing Hill,” “Azuma Arbour,” and “Trellissed Arbour” were a few of the names given to particular features of the grounds, some of which remain still intact.

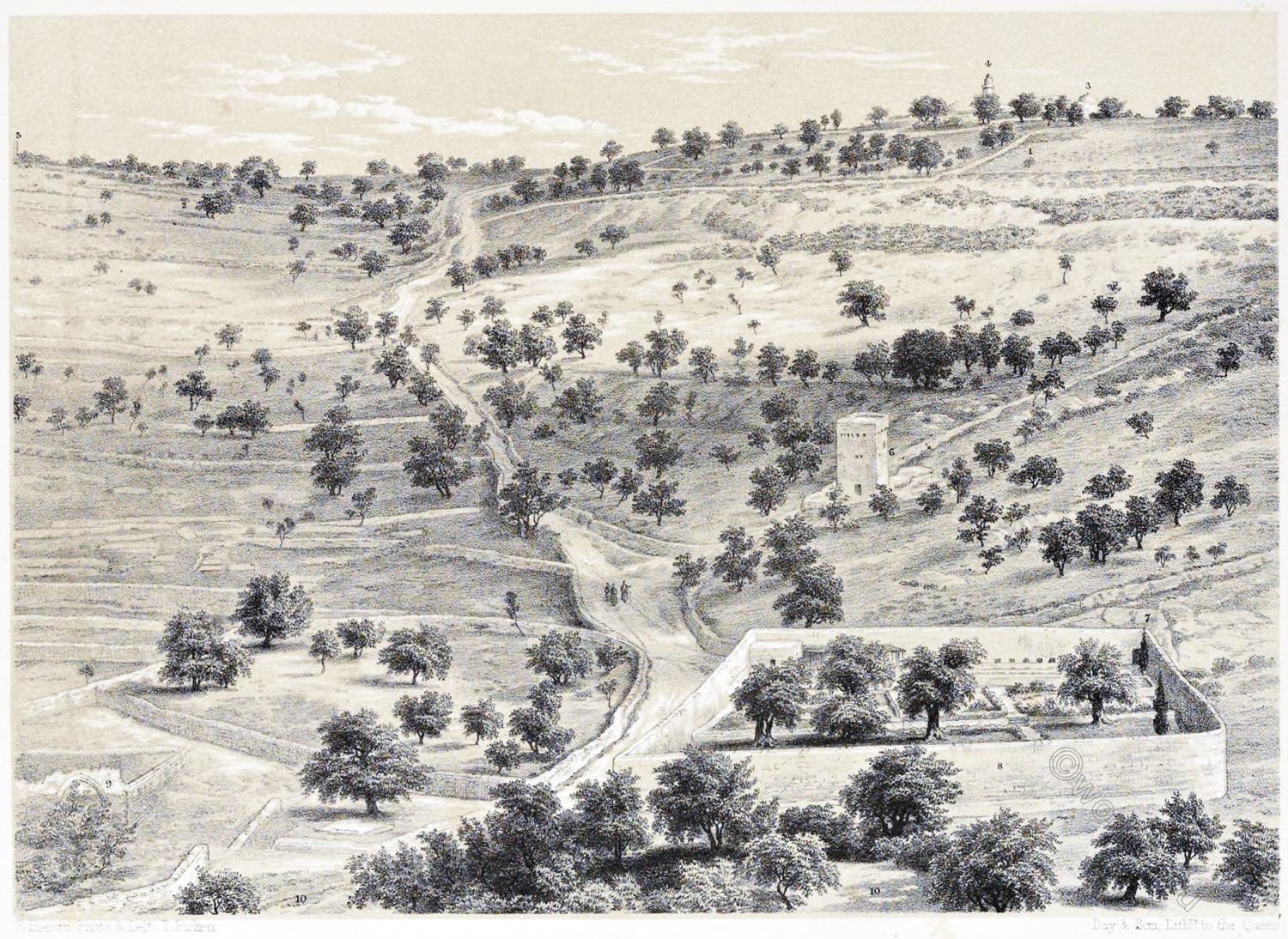

The upper illustration of Plate V shows the garden-lake and surrounding hillocks overgrown with evergreens and clipped bushes. In the centre of the lake may be seen one of the pine-clad islets connected to the shores by bridges.

The lower illustration exhibits the long double wooden bridge, with intermediate pavilion, which crosses the lake in two right angle lines. The further bridge is roofed with trellis-work, overgrown with wistarias which make a splendid show of flowers in the early summer. A large quantity of cherry trees of single and double blossom, planted on the lawns and hills surrounding the water, now form the chief attraction of this Imperial villa garden.

THE HAMA RIKIU GARDEN AT TOKYO

by Josiah Conder

This is another of the Imperial gardens of the capital taken over from the Shogunate at the time of the Restoration. It occupies a site which, until the middle of the seventeenth century, was merely a marshy level, fifty acres in area, overgrown with reeds and rushes, and used as a hawking ground by the Shogun. Iyetsuna presented the land to one of his relatives, who converted it into a garden, and furnished it with suitable buildings.

It became an occasional summer resort for the Regent and his Court, its position, on the shore of Tokio Bay, rendering it a cool and refreshing retreat, and obtaining for it the name of Hama Goten, or the Palace on the Coast. Records dating from the year 1708 mention the following garden structures: “Island Tea-house,” “Ocean Tea-house,” “Bubbling-spring Tea- house,” “Shrine of Kwannon,” “Shrine of Koshin,” *) and “Bridge of the Front Gate.”

*) Kwannon and Koshin are both popular deities, shrines dedicated to whom exist all over Japan.

An extensive conflagration in the year 1725 destroyed the buildings and damaged the grounds, which were remodelled under the Shogun Iyenari, at the end of the eighteenth century.

The principal detached pavilions then erected were: the “Swallow Tea- house,” “Pine-tree Tea-house,” “Thatched Tea-house,” “Pine-grove Arbour,” “Hut of the Salt-coast,” “Arbour of the Royal Mountain,” “Arbour of the Fifth Moat,” and “Azuma Arbour” — Azuma being an ancient name for Japan.

Just before the Restoration, in 1867, the estate passed into the hands of the Ministry of Marine, and in the following year was transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and used for entertaining foreign visitors of distinction. Eventually the Imperial Household Department took possession of the site, when the name was slightly changed to Hama Rikiu, or Detached Palace of the Coast, the term Rikiu being applied to all the secondary palaces or Imperial villas. Meanwhile, the garden had become much out of repair, only a few of the ornamental arbours remaining.

An old book, published in 1843 by Oyamada Yosei-O, a retainer of Prince Kwacho, gives the following account of the chief attractions of these grounds:—An elevated hillock called the “Mountain of Eight Views” afforded an extensive prospect of the sea and distant hills. Near its base was a small lagoon containing irises and other water-plants. “Ocean View Hill” was the name of another eminence overlooking the Bay planted with mountain grasses and pine trees.

In the western quarter of the garden, and providing an uninterrupted prospect of Fujisan, was another hill called “Fuji-viewing Hill.” Close to a rocky mound, covered with azalea bushes, was a beach arranged with artificial salt-making beds and kilns, designed in imitation of the primitive salt factories abounding on the Japanese coast. A few peasants’ huts embowered in high grasses and wild flowers, and a picturesque cottage, called the “Sea-shore Tea-house,”—from which a sea view, including the cliffs of the opposite coast could be enjoyed,—imparted a charming rural character to this spot.

Another feature of the garden was the “Embroidery Hall,” a detached building used for the manufacture of the beautiful Aya-nishiki, the working of which was formerly a favourite pastime of the Court ladies. A grove of pine trees, in which was buried a little arbour called the “Pine-grove Tea-house,” lined the approach to this hall. The “Thatched-hut Tea-house,” already mentioned, was constructed to resemble the hostelry of a country road, fitted up with the simple implements and furniture peculiar to country life. It is said to have been used by the Shogun as a hunting-box for hawking. A miniature structure, built in delicate taste, and called the “Swallow-Tea-house,” was furnished with several valuable Chinese pictures and other antique treasures of the So period. At the side of a winding pathway leading to the garden lake was a pretty bower, called the “Trellised Arbour,” overlooking a large bed of chrysanthemums.

Other buildings referred to were: the “Orchid House,” containing Chinese orchids and other rare plants arranged in flower-pots; a closed summer-house called Azuma-Ya; and a little fane to Azuma Inari, the Fox God, half hidden in a small plantation of trees suggestive of a temple grove. A hill, called Reiisan, gave a good prospect of the neighbouring garden of the Shiba Rikiu, to the south-west. It was rocky and precipitous on one side and adorned with crooked, overhanging pine trees, in imitation of the wild scenery of the Japanese coast.

From still another eminence, more than twenty feet in height, and named Kembanzan, the large trees of the distant Fukiage Garden could be seen. The cascade at the head of the lake, the water for which was brought from the river Tamagawa, was picturesquely designed. A striking feature of this garden is a long winding bridge crossing the lake, covered in parts with wistaria trellises, which are loaded with immense racenes of purple flowers in the season. The Hama Rikiu is now chiefly known for its unrivalled show of double cherry blossoms in spring, forming an attraction honoured yearly by an Imperial visit and reception.

Source: Landscape Gardening in Japan by Josiah Conder (1852-1920); Kengo Ogawa. Tokio: Kelly and Walsh, 1893.