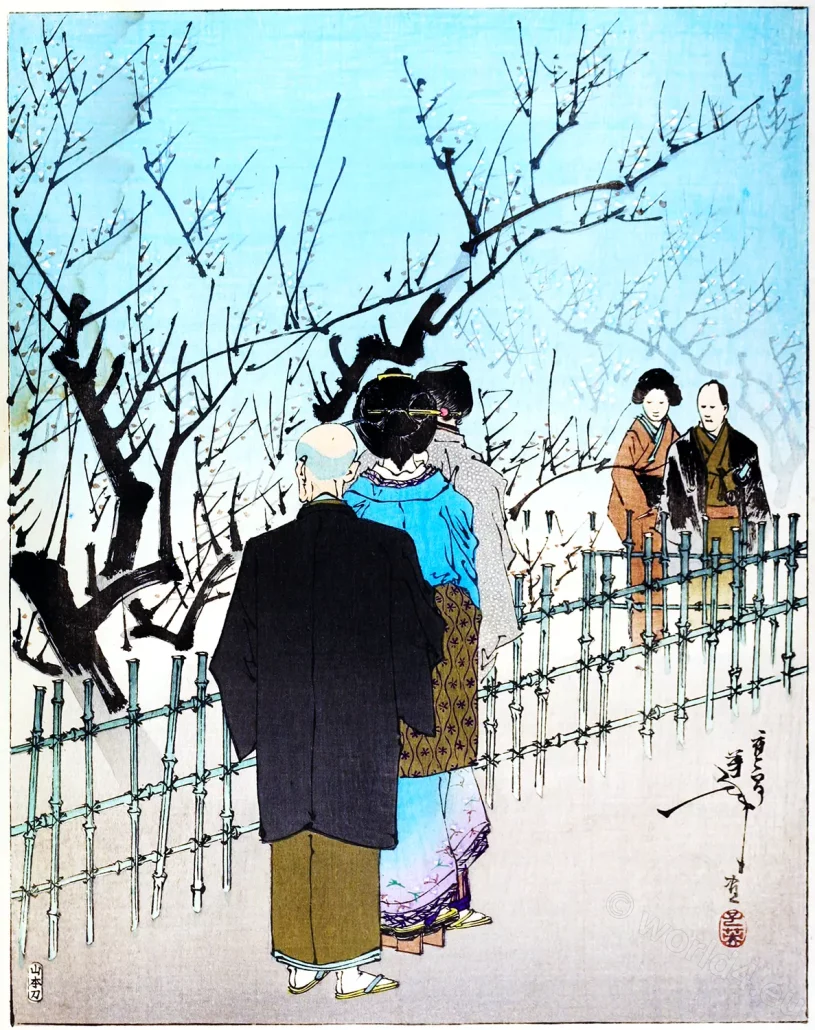

PLATE I. VIEWING THE PLUM BLOSSOMS.

SPRING FLOWERS. THE FLOWERS OF JAPAN.

PLUM BLOSSOMS

by Josiah Conder

Enriching the bare landscape with its bloom, and filling the air with its fragrance at a time when the snow of winter has hardly passed away, the blossoming Plum tree has come to be regarded with especial fondness by the Japanese. Combined •V with the evergreen pine and bamboo, it forms a floral triad, called the Sho-chiku-bai, supposed to be expressive of enduring happiness, and is used as a decorative symbol on congratulatory occasions.

The Plum blossom is often referred to as the eldest brother of the hundred flowers, being the earliest to bloom in the year. Quick in seizing the peculiar features which distinguish one growth from another, to the extent almost of a tendency to caricature them, the Japanese have been chiefly attracted by the rugged and angular character of the Plum tree, its stiff, straight shoots, and sparse, studded arrangement of buds and blossoms. Thus, a fancy has arisen for the oldest trees, which exhibit these characteristics to perfection. In them is shown the striking contrast of bent and crabbed age with fresh and vigorous youth ; and, as if to render more complete this ideal, it is held that the Plum tree is best seen in bud and not in full blossom.

The gardeners of the country, so clever in the training of miniature trees, find in the Plum a favourite object for their skill, imitating in miniature the same character of budding youth grafted on to twisted and contorted age. These tiny Plum trees, trained in a variety of shapes,—bent, curved, and even spiral,—with their vertical or drooping graftings of different coloured blossom-sprays, fresh, fragrant, and long lasting, form one of the most welcome room decorations during the first months of the year.

Poets and artists love to compare this flowering tree with its later rival, the cherry. With the latter, they say, the blossom absorbs all interest, whereas, in the case of the Plum, attention is drawn more to the tree itself: the cherry blossom is the prettier and gayer of the two, but the Plum blossom is more chaste and quiet in appearance, and has, besides, its sweet odour. The fragrance of the Plum blossom is constantly referred to in the simple poetry of the country, and the following free translation may be given as- an example of one of such verses:-

“In Spring time, on a cloudless night,

When moon-beams throw their silver pall

O’er wooded landscape, shrouding all

In one soft cloud of misty white,

T’were vain, almost, to hope to trace

The plum trees in their lovely bloom

Of argent, t’is their sweet perfume

Alone which leads me to their place.”

The custom of planting Plum trees in groves and avenues to form pleasure resorts during blossom time, seems to be of comparatively recent date; and some of the most famous Plum groves are really orchards, originally planted for the sake of the fruit. It is said, that in China, from whence Japan borrowed many of her customs and cults, this tree was first esteemed for its fruit alone, and in later and more aesthetic times it became honoured for its pure blossom and sweet scent.

In the earliest Japanese annals we read of a single Plum tree being regularly planted in front of the South pavilion of the Palace at Nara, which was replaced by a cherry tree in later times, when the latter had in its turn become the favourite of the Court. In connection with this Imperial custom, a pretty story is told explaining the origin of the name O-shuku-bai, meaning Nightingale-dwelling-plum-tree, applied, even to the present day, to a favourite species with pink double blossom and of delicious odour. Some time in the tenth century the Imperial Plum tree withered, and, as it was necessary to replace it, search was made for a specimen worthy of so high an honour.

Such a tree was found in the garden of the daughter of a famous poet, named Kino Tsurayuki, and was demanded by the officials of the Court. Unable to resist the Imperial command, but full of grief at parting with her favourite Plum tree, the young poetess secretly attached to its trunk a strip of paper upon which she wrote the following verse : —

“Claimed for our Sovereign’s use,

Blossoms I’ve loved so long

Can I in duty fail?

But for the Nightingale,

Seeking her home of song,

How shall I find excuse ?” Brinkley.

This caught the eye of the Emperor, who, reading the lines, enquired from whose garden the tree was taken, and ordered it to be returned. The season of the Plum blossom is made musical with the liquid note of the Japanese nightingale, and in the different decorative arts this bird is inseparably associated with the Plum tree. Similar combinations of bird and flower, or even of beast and flower, are numerous, and strictly followed in the many designs of the country; such, for example, are the associations of Bamboo leaves and Sparrows, Pea-fowl and Peonies, and Deer with Maple trees.

In later times Plum trees were planted in large numbers in rural spots near to the ancient Capitals, forming pleasure resorts for the ladies of the Imperial Court. Along the banks of the river Kizu, at a place called Tsuki-ga-se, in the province of Yamato, fine trees of pink and white blossom line the banks for upwards of two miles, diffusing their delicious scent around.

These trees are what remains of quite a forest of Plum trees said to have stretched for miles around. The modern Capitals have also their favourite Plum orchards, visited by crowds of sightseers in blossom time, at the end of January. Sugita, a village not far from Yokohama, possesses one of the most famous, having over a thousand trees, many of which are eighty or a hundred years of age, and which supply in the Summer most of the fruit consumed in the Eastern Capital, Tokio. It is popularly known and frequented for its blossoms alone in the early Spring.

This orchard boasts six special kinds of tree, distinguished by different fancy names having reference to the character of flower ; the principal of which are trees of pink, and others of green blossom,—for the white Plum flower has a faint tinge of emerald. In all, there are said to be sixty different species existing in Japan. The blossom held most in esteem is the single blossom of white or greenish white colour and of small size.

All the white kinds are scented, but of the red some have no perfume. There is an early Plum of red double blossom which blooms before the Winter solstice, and is of handsome appearance, but it has little or no scent.

Every visitor to Japan has heard of the Gwa-rio-bai, or Recumbent-dragon-plum-trees at Kameido, a famous spot in the North of Tokio. At this place there existed, up to fifty years ago, a rare and curious Plum tree of great age and contorted shape, whose branches had bent, ploughing the soil, forming new roots in fourteen places, and straggling over an extensive area. This tree, from its suggestive shape, received the name of the Recumbent Dragon, and, yearly clad with fresh shoots and white blossoms of fine perfume, attracted large crowds of visitors. From this famous tree fruit was yearly presented to the Shogun. Succumbing at last to extreme age, it has been replaced by a number of less imposing trees, selected on account of their more or less bent and crawling shapes. This present group of trees, inheriting the name and somewhat of the character of Recumbent Dragons, makes a fine show of blossoms in February, and keeps up the popularity of the resort.

Komurai and Kinegawa, near Kameido, also have blossom-groves much frequented.

Another noted spot is Komukai, near Kawasaki, on the Tokaido, not far from the Capital, historically famous as having been often visited by the Shogun, and possessing trees over two hundred years of age.

At Shinjiku, another place on the outskirts of Tokio, is a fine grove of Plums, popularly called the Silver-world (Gin-sekai), a term often applied to the snow-clad landscape, and having special reference in this instance to the silver whiteness of these blossoms.

Source: The floral art of Japan: being a second and revised edition of the flowers of Japan and the art of floral arrangement by Josiah Conder (1852-1920). Tokio : Kelly and Walsh, Ltd. 1899.