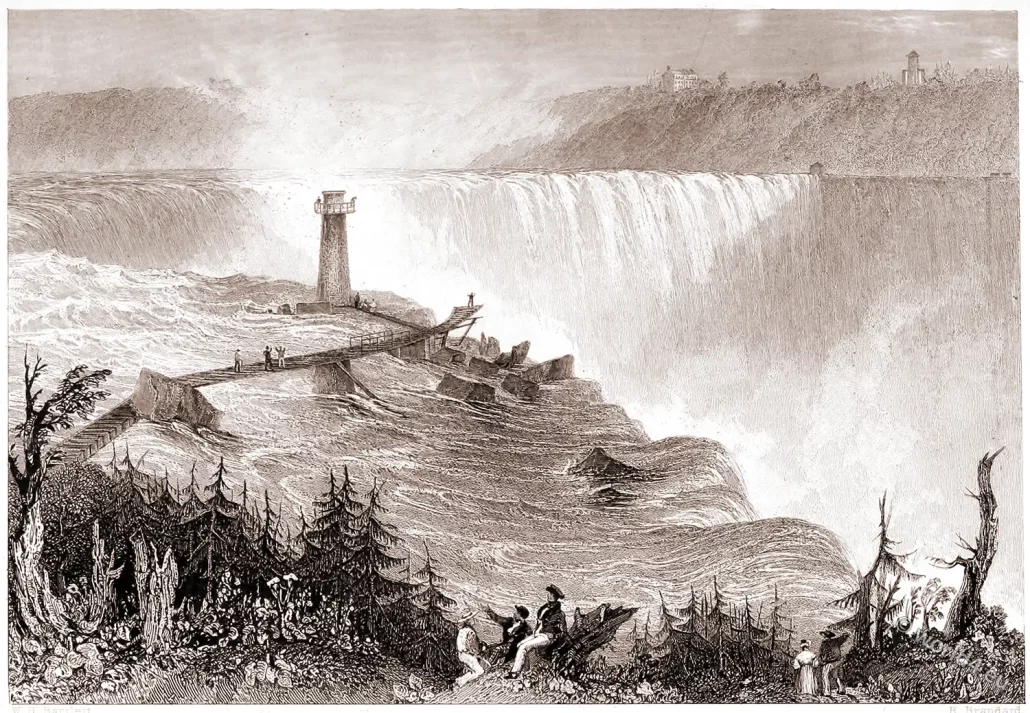

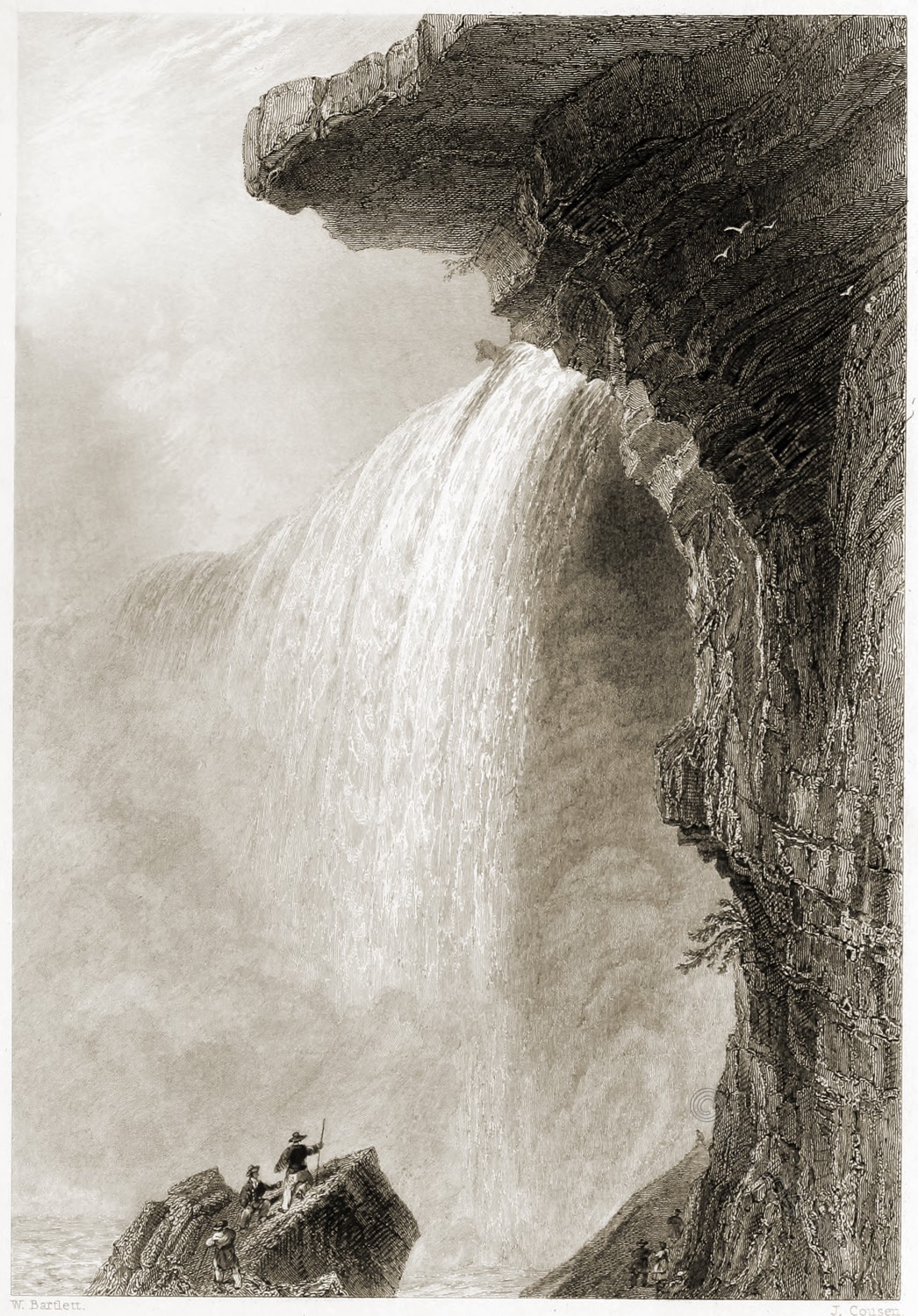

HORSE-SHOE FALL, AT NIAGARA.

(SEEN FROM GOAT ISLAND.)

By William Henry Bartlett (British, 1809-1854).

Niagara is the outlet of several bodies of water, covering, it is estimated, 150,000 square miles! Dr. Dwight considers the Falls as part of the St. Lawrence, following that river back to the sources near the Mississippi; and, doing away with the intermediate names of St. Marie, Detroit, St. Clair, Iroquois, and Cataraqui, he traces its course through the lakes Superior, Huron, Erie, and Ontario, as the Rhone is followed through the Lake of Geneva, and the Rhine through Lake Constance.

In this view the St. Lawrence is doubtless the first river in the world. It meets the tide of the sea four hundred miles from its mouth, which is ninety-five miles broad; and to this height fleets of men of war may ascend and find ample room for an engagement. Merchantmen of all sizes go up to Montreal, which is six hundred miles from the sea; and its navigation for three thousand miles is only interrupted in three places,— Niagara Falls, the rapids of the Iroquois, and the part called the river St. Marie. The St. Marie is navigable for boats, though not for larger vessels; a portage of ten miles (soon to be superseded by a ship canal) conveys merchandise around the Falls of Niagara, and the rapids of the Iroquois present so slight a hinderance, that goods are brought from Montreal to Queenston for nearly the same price as they would pay by unobstructed navigation. It is necessary to remember the extent of the waters which feed Niagara, to conceive, when standing for an hour only on the projecting rocks, how this them, to their extravagant delight, in red coats, and purchasing from them fish and fruits in abundance.

At this day there stands a villa on every picturesque point; a thriving town lies on the left shore; hospitals and private sanitary establishments extend their white edifices in the neighbourhood of the quarantine-ground; and between the little fleets of merchantmen, lying with the yellow flag at their peak, fly rapidly and skilfully a constant succession of steam-boats, gaily painted and beautifully modelled, bearing on their airy decks the population of one of the first cities of the world. Yet of Manhattan Island, on which New York is built, Hudson writes, only two hundred years ago, that “it was wild and rough; a thick forest covered the parts where anything would grow; its beach was broken and sandy, and full of inlets; its interior presented hills of stony and sandy alluvion, masses of rock, ponds, swamps, and marshes.”

The gay description which an American would probably give of the Narrows, the first spot of his native land seen after a tedious voyage,—would probably be in strong contrast with the impression it produces on the emigrant, who sees in it only the scene of his first difficult step in a land of exile. I remember noting this contrast with some emotion, on board the packet-ship in which I was not long ago a passenger from England. Among the crowd of emigrants in the steerage, was the family of a respectable and well-educated man, who had failed as a merchant in some small town in England, and was coming, with the wreck of his fortune, to try the back-woods of America. He had a wife, and eight or ten very fine children, the eldest of whom, a delicate and pretty girl of eighteen, had contributed to sustain the family under their misfortunes at home, by keeping a village school. The confinement had been too much for her, and she was struck with consumption—a disease which is peculiarly fatal in America.

Soon after leaving the British Channel, the physician on board reported her to the captain as exceedingly ill, and suffering painfully from the close air of the steerage; and by the general consent of the cabin passengers, a bed was made up for her in the deck-house, where she received the kindest attention from the ladies onboard; and with her gentle manners and grateful expressions of pleasure, soon made an interest in all hearts. As we made the land, the air became very close and hot; and our patient, perhaps from sympathy with the general excitement about her, grew feverish and worse, hourly. Her father, and a younger sister, sat by her, holding her hands and fanning her; and when we entered the Narrows with a fair wind, and every one on board, forgetting her in their admiration of the lovely scene, mounted to the upper deck, she was raised to the window, and stood with the bright red spot deepening on her cheek, watching the fresh green land without the slightest expression of pleasure.

We dropped anchor, the boats were lowered, and as the steerage passengers were submitted to a quarantine, we attempted to take leave of her before going on shore. A fit of the most passionate tears, the paroxysms of which seemed almost to suffocate her, prevented her replying to us; and we left that poor girl surrounded with her weeping family, trying in vain to comfort her. Hers were feelings, probably, which are often associated with a remembrance of the Narrows.

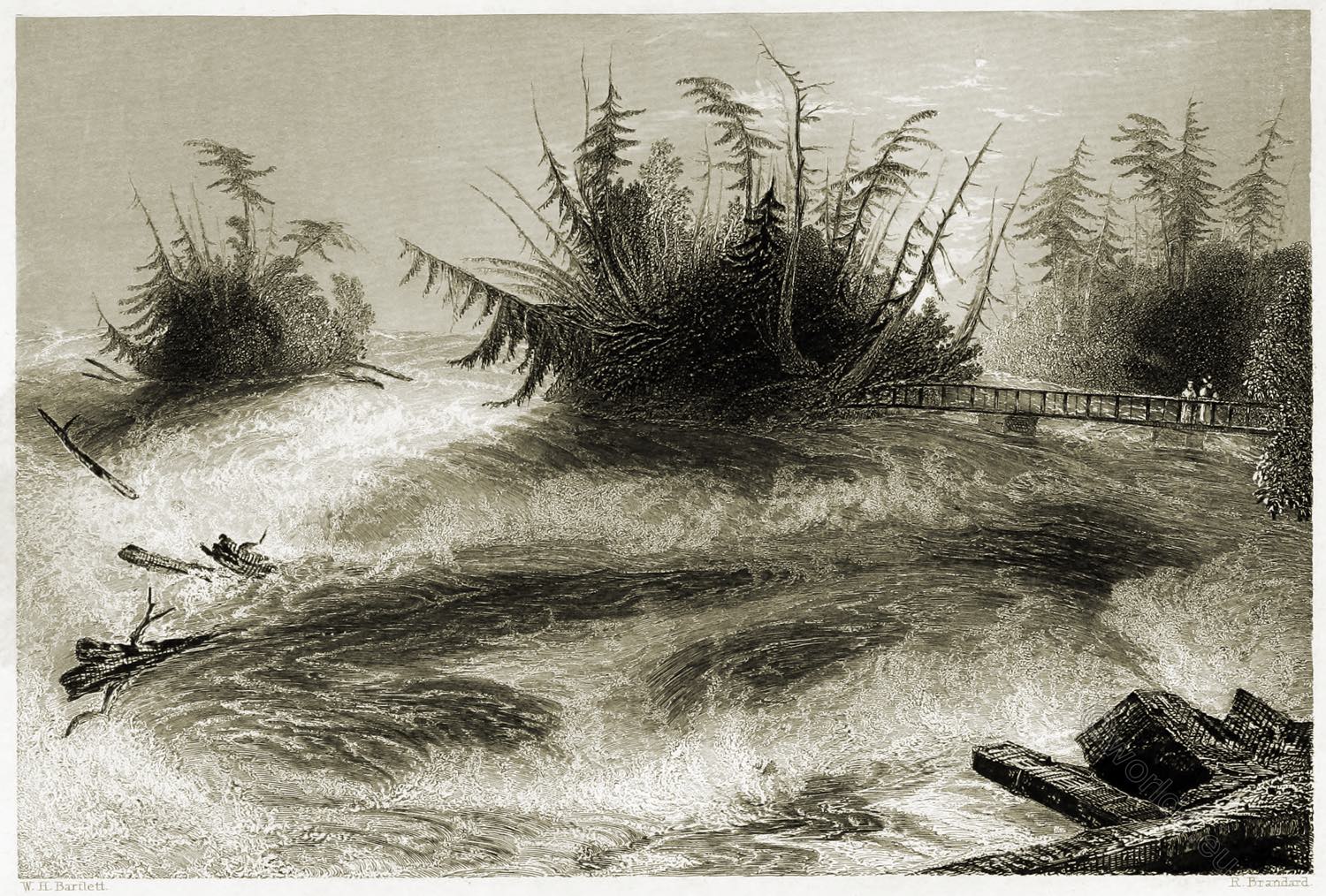

Source: American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature. From Drawings by W. H. Bartlett. Engraved by R. Wallis, J. Cousen, Willmore, Brandard, Adlard, Richardson, &c. The Literary Department by Nathaniel Parker Willis, Esq. London: George Virtue 26, Ivy Lane. 1840. Vol. 1.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.