One of the most interesting phases in Japanese art history was the rise of the “people’s school” (ukiyo-e ryū), which was now recruited from the artisan class.

Iwasa Matahei (岩佐 又兵衛, 1578 – July 20, 1650) of the early Tokugawa period, had foreshadowed this development in the sixteenth century; at the end of the seventeenth century, Hishigawa Moronobu, Hanabusa Itcho, Nishigawa Sukenobu, and other artists of gentle birth took up the tradition, the first of these being the originator of artistic book illustration.

But the culminating period of this school did not come till the eighteenth century, when the profession of drawing for engravers fell into the hands of commoners, of whom the earliest to win fame for their colour prints of actors and professional beauties were the Torii and Katsugawa families.

The best artists in nishiki-e (錦絵, “brocade picture”, multi-coloured woodblock printing; the technique is used primarily in ukiyo-e), as these colourprints are termed, were Utamaro, Torii Kiyonaga, Suzuki Harunobu, and Koryūsai, together with their more popular successor Hokusai (1760-1849), whose ceaseless activity in illustrating books, drawing broadsides, and producing the more delicate little compositions called surimono, covered an immense range of subjects quaint, humorous, and homely.

Of Hokusai’s fellow-workers the name is legion. Pre-eminent among them were Toyokuni, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada of the Utagawa family, who succeeded the Katsugawa as theatrical draughtsmen, and such guidebook (Meisho) illustrators as Shuncho-sai and Settan. In addition to these were Hokkei, Keisai, Eisen, Ryūsen, Shigenobu, Hiroshige, and many more of lesser note.

Utagawa Toyokuni (1729-1825)

A brilliant artist of high repute in his day. Some of his prints, especially the earlier ones, are of distinguished quality.

Utagawa Toyokuni, born in Mishima-cho, Shiba-Shinmei-mae, Edo, whose real name was Kurahashi Kumakichi, later Kumaoemon, also called Ichiyōsai, and who lived from 1769 and died on February 24, 1825, began his activity about the middle of the ninth decade and continued it until about 1810.

He became, towards the end of Utamaro’s career, his most notable rival. While he did not possess the strength and boldness of Yeishi and Utamaro, he yet commanded a wholly individual and well-considered style.

He won a special significance for the further development of the nineteenth century by his having trained Kunisada, who later called himself Toyokuni II., and Kuniyoshi, both of whom dominated art until the middle of the century, and gave it its essential stamp.

Toyokuni was the son of Kurabashi Gorobei, a Buddhist carving doll maker in Yedo; after moving from Mishimamachi to Yoshimachi and Horie-machi, he first studied the style of Hanabusa Itcho (英 一蝶) and Giokusan (Houseki no Kuni 宝石の国), but went over to Utagawa Toyoharu, the founder of the Utagawa school, and took the name Utagawa Toyokuni, and became enormously popular for his paintings of actors and beauties that expressed ideal beauty. He formed his name by taking part of that of the old Toyonobu, as Fenollosa assumes.*) Unlike Yeishi and Utamaro, therefore, he had no need to familiarise himself with the popular style, but was from the start educated in a conception not over far removed from that of the still dominant Kiyonaga.

*) Anderson Cat., p. 348; Strange, p. 475; Fenollosa Cat., Nos. 337-356; Bing Cat., No. 199 ff.; Cat. Goncourt, No. 1283 ff.; Cat. Burty, No. 258; Goncourt, Outamaro, pp. 187, 103 ff. The biographical dates are corrected according to the Hayashi Cat.

Toyokuni was without doubt Toyoharu’s greatest pupil. He understood how to dispose his mostly very quiet figures in graceful groupings; although his colouring lacks a special originality, yet it was strong and in good taste.

After Kiyonaga had given up actor representations, Toyokuni took over this field; he began to depict actors off the stage, in land and water picnics, or in the company of beautiful women; but as he treated these subjects carelessly, this branch of art fell into a temporary decay until his pupils took it up again with renewed energy. Towards the end of the ninth decade he developed his full strength and independence, in a style reminding us of Kiyonaga.

The European influence, which had already become noticeable in Toyoharu, his teacher, may be clearly traced in his work also. From the middle of the nineties he began to approach more nearly the style of Utamaro. About 1800 his figures also reached an impossible length, and his faces rounded into a long-drawn oval. He then developed, in rivalry with Utamaro, a peculiar angular style, which reached its height in 1804, and displays him, even in comparison with his former model, Kiyonaga, as a wholly independent artist of a peculiar and austere grace.

Except for the time when he, too, was unable to withstand the universal taste for the exaggerated, he retained always a relatively high degree of naturalness; and where he appears unnatural, it is generally to be explained by the affected attitudes of the actors of the time.

Later on, however, his works become coarser. He and Kiyonaga were probably the first to make use of the bluish red which introduced a staring tint hitherto unknown to Japanese wood-engraving.

There can be no suggestion of their having employed aniline dyes, as these were not put on the market by Perkins until 1856 and probably did not reach Japan until the sixties. Still, we cannot but feel the extreme gaudiness of the general effect, which appears towards the end of the eighteenth century to be a foreign element and a falling off, perhaps under the influence of China, from the older Japanese seriousness of purpose.

It is only because this delicate and bright colour-scheme, which correspondingly modifies the yellows and blues as well, has preserved its original freshness in but very few copies, that we do not recognise it more immediately as a characteristic feature of precisely this period.

Immediately after Toyokuni retired from the field, his pupil, Kunisada, about 1810, continued the activity of his master, at first under his own name; about 1844, however, long after his master’s death, that is, he assumed Toyokuni’s name. A likeness of Toyokuni is found in Kuniyoshi’s Fuzoku komeidan, Anecdotes of Celebrated People, two small volumes, in black and white (Kioto, 1840), on the last page.

Like Hokusai, whose first period he lived through, Toyokuni illustrated tales of Kioden, Bakin, and others. With Kunimasa he published, at the beginning of the nineties, a series of actor pictures, for which Utamaro drew the title; in 1801, he published alone a collection of actor pictures of small size, which may be considered about his best work; in 1802, there followed the representations of women of all classes.

Besides his numerous triptychs, the pleasing picture, in ten small sheets meant to be pasted side by side, of a rain shower driving a throng of people of every trade to seek shelter under a gigantic outspread tree, is particularly celebrated. His landscapes are rare.

He also rendered flowers on a large oblong surimono. Illustrations in Strange: plate v., a garden scene, early; on page 48, an actor; on the same, a woman floating a little boat, reminding us of Utamaro. Gonse, i., p. 42: courtesans in a boat (part of a triptych). Fenollosa (Outline, pl. xvi.) reproduces a print of his decline.

Of his triptychs the following may be cited:—

- Snow scene, a lady of rank with her little daughter making snowballs; dated by Fenollosa (No. 348) about 1798; perhaps his most beautiful work of the kind.

- A lady of rank on horseback with attendants, Fuji in background; a very beautiful composition, in subdued colours: yellow, violet, black, and a little green.

- The ford, a lady of rank carried in a palanquin by eight men.

- The gust of wind.

- Women as gods of fortune in a ship, the prow of which has the shape of a white cock.

- Actors and women in a boat on the river; dated by Fenollosa (No. 353) about 1805.

- Washerwomen at the whirlpool.

- Haul of fish on the shore.

- The bath; according to Fenollosa (Nos. 351, 352) about 1803.

- The banks of the Sumida River at the bridge of Riogoku.

- A fan shop, in front a boy playing with five puppies; dated by Fenollosa (No. 338) about 1789; one of the best of his early period.

- The rat-dream; according to Fenollosa, about 1794.

- Three actors (Catalogue Duret, No. 91).

- Scene in a temple garden, dated by Fenollosa (No. 342) about 1800.

In collaboration with his pupil Toyohiro.

Pentaptych: main street of the Yoshiwara in cherry blossom time; dated by Fenollosa (No. 341) about 1792.

Series of sheets:—

- The rain shower, 10 small sheets; among those seeking shelter under the giant tree in the middle of the long design are a young nobleman with a falcon, a young girl trying to cover his hair, a washerwoman, a man with a monkey, a faggot carrier, and several blind people, who have fallen down in their haste (Bing Catalogue, No. 208).

- Views of the environs of Yedo, 8 sheets, quarto, dating from the beginning of the century (Catalogue Leroux).

- The six Tamagawa rivers, in circles, only slightly coloured.

- The six celebrated poets, in pairs.

- Courtesans in the likeness of Komachi, 7 sheets, medium size.

Illustrated books:—

- Haiyu raku richutsu (?), pictures of Yedo actors, in collaboration with Kunimasa, beginning of tenth decade; the title by Utamaro, representing the implements of the No-dance; by the same is an actor seated, smoking and watching three women leaving the theatre.

- Yakusha konotegashiwa, collection of celebrated actors, 2 small vols., Yedo, 1801; perhaps his best work.

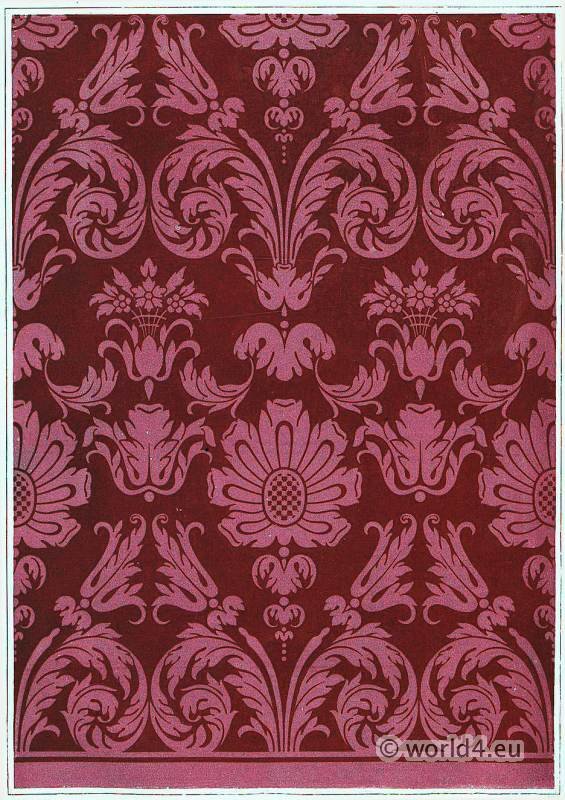

- Ehon imayō sugata, the manners of the present time, women of all classes, 2 vols., coloured, 1802. Edo: Kansendō/ Izumiya Ichibei; in the first volume respectable women, in the second, those of the Yoshiwara, Edo’s licensed prostitution district or “pleasure quarters.”) &c. (see picture above)

- Toyokuni toshidamafude, reminding one of Hokusai’s Mangwa.

- Yehon Yedo no mizu, Yedo, 3 vols., black and white.

- Yobo shashin sangai kio, Recreations of Actors, Yedo, 1801, 2 vols.; excellent in colour.

- Bakino, Comparison of the Theatres with Famous Places, 1800, 2 vols.; humorous.

- History of Princess Sakura, a romance by Kyoden, Yedo, 1806, 5 vols.

- Yakusha awase kagami, Actors, Yedo, 1804.

In collaboration with Shunyei he published a work at Yedo in 1806; in collaboration with Toyohiro: Otagi Kanoko, 12 coloured pictures, Yedo, 1803.

His best pupil was his brother, Toyohiro, who developed a peculiar manner, and later had the privilege of training the great landscape painter Hiroshige. Of Toyokuni’s pupils, Kunisada (later Toyokuni II.), and Kuniyoshi, both of whom will be mentioned later, attained the widest celebrity.

Pupils of his early period were Kunimasa (see above) and Kuniyasu (Hayashi Catalogue, No. 1092), who produced especially actor prints, but whose works are rare. Kunimasa lived from 1773 to 1810; he also signed himself Ichiyusai. Illustrated in Hayashi Catalogue, No. 1088; Duret (No. 267) mentions one book. His son, Naajiro, was also his pupil; he first took the name Toyoshige, but later adopted his father’s name, so that he must be carefully distinguished from Toyokuni II.; sometimes he signs himself Gosotei Toyokuni. His style is reminiscent rather of Yeisen than of his father.

Rushing ahead

Like cloud shadows!

Like a charcoal drawing

Soon blurred!

Source:

- Japanese colour prints and their designers, by Japan Society (New York, N.Y.), 1913.

- A history of japanese colour-prints by W. von Seidlitz. Publisher: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1920.

- Japanese illustrations; a history of the arts of wood-cutting and colour printing in Japan by Edward Fairbrother Strange (1862-1929). London, G. Bell and sons, 1904.

- A handbook for travellers in Japan, including Formosa by John Murray (Firm); Chamberlain, Basil Hall, 1850-1935; Mason, W. B. New York, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

- The Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Utagawa Toyokuni und seine Zeit by Friedrich Succo. München: R. Piper, 1913.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.