SERPENT WORSHIP IN AFRICA

by Wilfrid Dyson Hambly.

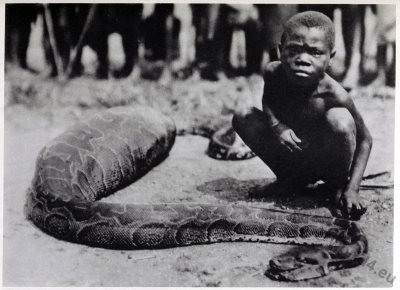

I. PYTHON WORSHIP

In his “Description of the Gulf of Guinea” (1700) Bosnian describes the python worship of Whydah, in Dahomey, as follows: “Their principal god is a certain sort of snake which professes the chief rank among their gods. They esteem the serpent their extreme bliss and general good.”

This account remarks on the connection of the serpent with trees and the sea. “The snake is invoked in excessively wet, dry, or barren seasons, and on all occasions relating to government.”

At that time even the king sent presents to the snake house, “but I am of the opinion,” says Bosman, “that these roguish priests sweep all the offerings to themselves, and doubtless make merry with them.” Then follows a description of the snake house, and a reference to the decline of the custom of presentations from the king to this institution.

In Bosman’s day there was a superstition to the effect that the sacred snake appeared to the most beautiful girls in order to induce madness. Such girls had then to enter the service of the snake temple. Bosman states that the priests persuaded the girls to feign frenzy so that they might be sent to the snake house.

On the whole, this account is well substantiated by many subsequent observers who have left reports deserving of comparative study. In addition to this there are still in circulation folklore stories which describe the aggressive attitude of the snake toward beautiful girls.

The python house

Burton (1864) states that at Whydah the snake was associated with trees and the ocean in acts of reverence. The python house (Plate III) is described as being only a cylindrical hut of clay covered by a thatched roof of extinguisher shape.

Two long, narrow, door less entrances faced each other. They led to a raised platform of tamped earth on which there was nothing but a broom and a basket.

The house was white washed, inside and out. A little distance from the entrance were small pennons of red, white, and blue cottons tied to some tall poles.

In addition to the python the crocodile and the monitor were local objects of worship. There were seven pythons reposing on a ledge where the wall joined the roof.

These reptiles often wandered at night, and on one occasion Burton saw a native bring one of them back to the hut. Before raising it he rubbed his right hand on the ground, and dusted his forehead as if grovelling before a king.

In former times the man who killed a python, even accidentally, was condemned to death, but a fine was later substituted for capital punishment.

The extreme penalty, of which Duncan gave a detailed description (1847), was death by burning. The culprit was usually clubbed to death as he rushed from the burning hut to the river. In the words of Burton he was “mercilessly belaboured with sticks and pelted with clods the whole way by the fetish priests.”

The account of Skertchly (1874) agrees well with that of Burton. Skertchly adds the information that a man who accidentally meets a python has to pay a fine when he returns the reptile.

Ordinary snakes may be killed with impunity. When a child is touched by a python, the parents have to consent to the adoption of the child into the python priesthood, and in addition they are required to pay for his training.

Danh is a potent fetish of Whydah and tutelary guardian of the python. There are no images of the python, and “adoration” is paid to the living creature only.

The snake wives

There are snake wives; these are women concubines of the priests, ostensibly devoted to service in the temple. The python priests are very numerous. When a devotee goes to the python priests, they collect a fee and promise that his wishes shall receive attention.

Dahomey

In describing the Ewe-speaking people of the Slave Coast, Ellis is more explicit on some of the foregoing points. Danhgbi is the deity of the python that is worshiped in Dahomey, especially at Whydah, Agweh, and Great and Little Popo.

*) The Kingdom of Dahomey was founded in the 17th century and existed until the end of the 19th century, when it was conquered by French troops from Senegal and later became part of French West Africa.

The snake itself is not worshiped, but rather its indwelling spirit, the outward form of the python being the manifestation of the god.

Ellis proceeds to explain the connection of the python with gods of war. He states that before 1726 python worship was new to the Dahomeyans, who were often at war with the people of Whydah, where python worship had been in vogue for an unknown period. On one occasion the pythons do not appear to have performed their defence of Whydah with success.

The attacking Dahomeyans, according to Snelgrave, seized the sacred pythons, saying, “If you are gods, speak and try to defend yourselves.” There was no response to this challenge, so the Dahomeyans killed and ate the pythons.

On another occasion the pythons seem to have acquitted themselves more gallantly in the defence of Whydah against the Dahomeyans. On this memorable day the python god actually appeared and caressed the faltering soldiers with his tail and head. The chief priest held the python aloft, and so encouraged his men that they carried everything before them.

A splendid temple was built at Savi for the python god Danhgbi; here the priests preserved the python which led them to victory.

There is a popular idea, says Ellis (1890), that the snake who led the way to victory still lives. He resides in a tree to the top of which he climbs every morning and hangs down to measure his length. When he is long enough to reach the earth, he will be able to reach the sky.

The python god

The python god is the god of wisdom, earthly bliss, and benefaction. The first man and woman were blind, but he opened their eyes. White ants are the messengers of the python. Whenever a native sees a python near a nest of white ants, he places round the reptile a protecting circle of palm leaves.

Images of the python are made in iron; these are representations of both the male and female reptile. Along with offerings of this kind are gifts of water in calabashes. All offerings have to be placed near to the banks of rivers or on the shores of lagoons, for the python god loves water.

In the enclosure round the temple are sacred trees. Snakes are free to wander, but the priest retrieves them. Before he does so, he purifies himself by rubbing certain fresh green leaves violently between the palms of his hands. Then prostrating himself before the reptile, he carries it gently home.

Opposite the python house are the schools where any child who has been touched by a python has to be kept at the expense of the parents, so that he may be taught the songs and dances peculiar to the worship.

In olden days adults were similarly liable. Not even the wives and daughters of the most influential chiefs were exempt from this penalty attached to contact with a python.

A native who meets a python says, “You are my father and my mother.” The native then cries to the god, “My head belongs to you, be propitious to me. “The punishment for a native who kills a python accidentally is burial alive. For the same offence a European was to be decapitated.

Ellis continues with stories of natives running the gauntlet from the burning hut to the river. One of his stories is from Des Marchais (1731). Ellis is, however, more than a compiler of extracts, for he himself was on the West Coast (1886-90)

Ellis mentions two thousand wives of the python temples; these are secretly married to the priests with unknown rites of initiation. It is probable that the priests consummate the union.

The ordinary duty of the wives is to bring water for the pythons, to make grass mats, to decorate the temple at festivals, and to bring food for the dancers. In these rites there are excesses in which the wives give themselves up to libertinage.

They say the god possesses them, and he it is who makes them pregnant. Ellis notes that by 1890 there was a decline of custom noticeable, if comparisons were made with the year 1886. The annual procession was abolished; so also were the severe penalties for offences against the python god.

“The temple is now visited only once a year by the headman of Whydah, who presents animals for sacrifice, while invoking the good offices of the god on behalf of the king and the crops.”

In former times, on the evening preceding the procession, the priests and Danh-si (python’s wives) went round the town, announcing the approach of the festival. They warned all the inhabitants to close their doors and windows, also to abstain from looking into the streets.

The natives believed that the penalty for watching the procession would be an attack by maggots which would burst from all parts of their bodies.

The priests and wives armed themselves with clubs on the morning of the great day. Then they ran round the town, clubbing to death any dogs, pigs, and fowls that were wandering in the streets.

This was necessary, because animals might annoy the python god. It was said that dogs worried him by barking, while poultry pecked at his eyes.

A hearty meal reduced the python to a comatose condition in which he allowed himself to be carried round in a hammock with the procession.

First came a body of priests and wives armed with clubs for the destruction of stray animals. Following them were men beating drums and blowing horns. Next followed the hammock in which the python was reposing, and round this danced four priests and four wives, quite naked. The procession continued a whole day, and at night an orgy was held in the python’s honour.

At minor festivals, which were held three times a year, everyone was allowed to take part in the revelry, which included dancing, feasting, and singing. On these occasions the priests drank rum mixed with blood.

Before the offering of a human sacrifice the wives danced with strange contortions while balancing earthenware jars on their heads.

They said possession by the god enabled them to do this. Public processions in honor of Danh-gbi were held in times of pestilence, war, and drought. On such occasions human victims were sometimes sacrificed.

When describing the Tshi-speaking people of the Gold Coast (1887) Ellis gives an instructive instance of the rise and fall of a cult.

In the year 1824 the Fantis gained an unexpected victory over the Ashantis, who had usually proved to be their masters. The happy victors attributed their success to the intervention of a god.

This surmise was confirmed by the priests who named a local god as the giver of victory. It is not clear that this deity was a python god, but some time after the Fantis had established a cult of their benefactor, he became identified with snakes which swarmed in the locality.

Furthermore, the god was thought to present himself to his worshipers in the form of the deadly ophidia. Other snakes which accompanied him were regarded as his offspring and dependents.

The first sacrifices were human beings, but later eggs were substituted. If the god did not present himself at the expected time,the priests made search for the offender, who was heavily fined. The god did not always assume the form of a serpent; he might manifest himself as a leopard.

When undisguised, he was of monstrous shape and black in color. The cult, which flourished from 1824 to 1867, became extinct when troops occupied the site and cleared the neighbourhood of snakes.

Rattray’s description of reverence for the python in Ashanti includes statements which might reasonably be regarded as evidence of a decadent python cult. But the information is more correctly classified under totemism.

Johnston refers to divination by observation of tame snakes in Liberia. The snakes usually employed are the pythons (Python).

In eastern Liberia, behind the Kru and Grebo countries, practices strikingly like the snake worship of Dahomey exist in many villages.

Büttikofer *) has statements which suggest that further research in the hinterland of Liberia would bring to light confirmatory evidence.

*) Johann Büttikofer (1850-1927) was a Swiss zoologist.

Büttikofer states that in several districts there were guardian animals of which the python was one. Near a lake in Buluma a python of the species sebae (the large python of Africa), was seen creeping about. No one dared harm the reptile; on the contrary, it was guarded and fed. This was the only instance of its kind noted in Liberia, and it recalled to the observer the python cult of Dahomey.

The word Mossi is applied to a large group of peoples who inhabit the region on the southern side of the great bend of the river Niger. Mangin mentions the serpent as one of several animals which are kept in sacred groves in this region.

Within the enclosure the animals, which include the crocodile and the leopard, are respected, but they may be killed if away from the sacred grove. The python is in some localities regarded as the guardian of the village.

The reptile contains a guardian spirit which will accompany a traveler on his journey if asked to do so. It is forbidden to cut down or even to gather wood in the sacred grove. Every attempt is made to prevent a stranger from violating the sacred wood, but if restraint is impossible, the people will offer a sacrifice on his departure.

The Hostains-d’Ollone Mission to the French Sudan (1898-1900) reported that the Sapos have fetish serpents in two houses encircled by a sacred enclosure, though the reptiles are sometimes to be seen loose in the village. These serpents are evidently not pythons, because according to the report these dangerous serpents are captured by a man who knows how to handle them with impunity

The natives say that these snakes give protection to the village and that they remain harmless by divine command.

It is not until Nigeria is reached that there is evidence of python worship in any way comparable to that of Dahomey. The art of Benin certainly suggests the importance of the snake in decorative design on bronze castings and wood carvings.

Nyendael (1704) describes a metal snake of good workmanship on the city wall. There was also a large metal serpent on the king’s palace.

Leonard, who studied ophiolatry in the Niger Delta, says that the pythons of Benin symbolised the war god, Ogidia; they were brought from Benin to Brass by a chief, Alepe, some twelve generations ago.

All over the Niger Delta ophiolatry exists. Irrespective of locality the serpent revered is the python. These creatures are fed and pampered to such an extent that they become a public nuisance.

In many districts of southern Nigeria the python is the principal object of ancestral adoration. Known in Brass under the name of Ogidia, it represents the tribal war god of the people.

The god at times takes possession of the priest, who then speaks in a dialect from Old Calabar, instead of the Brass dialect.

The priest induces possession by lying in the mud of the river for seven days without food, but during this time he has a quantity of rum.

The priest, when possessed, will prophesy wars and their results, accidents and other events, which may be avoided by sacrifices.

Straying pythons are carried to their reservation in the bush by the priest, who must first perform a special ceremony. When the reptiles are of enormous size, they are transported on stretchers.

Very seldom is a human being attacked by a python, but, if such an event happens, the priest is the only one who may effect a rescue. If a python has to be carried to the sacred enclosure because of its depredations, its prey is allowed to remain with it. The snake is handled carefully so that it may not be annoyed or hurt.

Anyone who fails to report an accidental injury to a python is cursed by the ancestral spirits, who inflict sickness or death. These penalties may be avoided by intervention of the priest.

The punishment for wilfully killing a python is death. This sentence may, however, be remitted if the offender pays a fine, offers a sacrifice, and takes a bath in sacred mud.

“These rules are milder than they were before the days of British administration. Formerly the penalty for killing a python was death even in the case of a chief. Old penalties survive in the interior districts.”

A public levy is made for giving elaborate burial rites when the python dies from natural causes. Every python has a human soul within it; this must be liberated by ritual after the death of the reptile. Any of fence against the snake is an offence against the ancestor.

When a python has been killed, the people will not admit the extermination of their ancestor.

Talbot (1912), Thomas (1914), and Basden (1921) have all reported on the subject of python cults (probably the term worship is justifiable) in southern Nigeria. The evidence from these observers may be briefly summarised as follows:

Talbot gives a description of the river Kwa and adjacent lagoons in whose dark waters dwells Nimm, the terrible, who is always ready at the call of her women worshipers to destroy those who have offended.

This goddess manifests herself as a huge snake or as a crocodile. In Ekoi mythology the cults of snakes and crocodiles are found to be closely connected. The python shares with the crocodiles the guardianship of the sacred lake.

The snake is used as a design in relief on the far wall of Egbo houses. A snake is never driven from the houses of those who belong to the cult of Nimm. Such people strew powdered chalk before the reptile, taking care not to frighten it.

If a snake enters a house not protected by Nimm, the owner must consult a diviner to find out whether the reptile has been sent by ghosts or juju.

Sacred waters

The sacred waters of Ndem near Awa are one of the places where sacrifices are made to the python spirit in the lake. The victim, usually a white cock or a white goat, is beheaded so that the head falls into the water.

If the head floats, the omen is good, for Ndem will take it away to devour. Should the offering sink, the sacrifice must be repeated. Surplus flesh may be eaten in the adjacent forest; but the man who takes any meat home will die before the moon and stars have risen.

Priest of the Holy Water

The only person allowed to make a sacrifice is one of the family of the “Priest of the Holy Water.” No person may approach the sacred pool except under the leadership of the priest.

In describing the python worship of Dahomey there was evidence that the reptile was associated with success in war. Talbot gives a legend of Nigeria which associates the python with warfare.

The python stiffened his body, so allowing some defeated troops to cross a river. The python relaxed his body and submerged the pursuers in the river when they attempted to follow. “Ingratitude, none of the people whose ancestors were thus saved, kills or eats the python to this day.”

Talbot relates that in 1909 one of his carriers killed a python. Immediately there arrived a deputation of chiefs followed by a crowd of people. These demanded the hatchet with which the reptile was killed, the dish on which the parts had been placed, and a fine to appease the ghost lest it should return to trouble them.

Continuing with the personal investigations of Talbot, there are several python cult concepts which are important because of their corroboration of evidence already adduced.

Priests and priestesses

Among the Bini, the chief juju in the Badagri region used to be the Idagbe, whose symbol was a large black python. To this creature an annual sacrifice of a bullock, fish, and beans was made.

For this purpose the priests removed their fine garments and put on simple white cloths before they sat down near the shrine. The people were blessed by sacred water which the priests threw from the sacred juju pot.

There were both priests and priestesses, the latter being more numerous. The sacerdotal offices, which were usually hereditary, involved a long and arduous training. The priestesses, like those of the Dahomeyans, would go into ecstasies in which they revealed the future.

Beliefs held by the Ijaw are of particular interest because these people are probably the oldest inhabitants of Nigeria.

The Ijaw *) think that pythons hold the spirits of the sons of Adumu, himself a python, and the chief of the water spirits. Women are forbidden to mention his name or to approach his temples.

*) The Ijaw (also known as Ijo or Izon) are a people in the Niger Delta

At times lights may be seen gleaming below the surface of the water which this python deity inhabits. On some occasions the lights rise to the tops of the palmtrees.

Serpents are carved on the statue of Adumu at Adum’ Ama on a small tributary of the Santa Barbara River. Here come all who aspire to act as diviners or prophetesses.

Such a priestess is forbidden to have relationships with a man; her husband is one of the sacred serpents. Every eighth day the water spirit is supposed to rise out of the water in order to visit his wife.

On that day she sleeps alone, does not leave the house after dark, and pours libations before the Owe (water spirit) symbols.

Python god Adumu

Inside her shrine are posts and staves representing serpents whose coils are said to typify the whirling dance performed in honour of the chief python god Adumu. “It is the spirit of the python that enters the priestess, making her gyrate in the mystic dance and utter oracles.”

When inspired, she will dance for a period varying from three to five days, during which she may not drink water. The language spoken during trance is said to be incomprehensible to the worshipers.

In the Brass country, where Ogidia, the python war god, is worshiped, there are three main festivals in his honour. At the first of these (Buruolali), there is a presentation of yams at night, by a woman.

Indiolali ceremony

These yams, which have been procured by the priests and chiefs, have to be in the form of serpents. At a second ceremony, a smooth-skinned male is offered as a sacrifice (Indiolali ceremony).

Thirdly, there is Iseniolali. At this rite, women who have been appointed by the chiefs and priests gather shellfish. These are cooked at the shrine of Ogidia amid great rejoicing.

Among the Ijaw people, pythons are never killed because they are thought to bring a blessing on any house they enter. At death the reptiles are buried with the honours of a chief.

Speaking of the Ibo people, N. W. Thomas says that entry of a python into the house is a favourable omen. Minor deities inhabit the bodies of snakes.

Pythons are held sacred throughout the region of marsh lands and waters inhabited by the most ancient tribe of all, the Ijaw. There are traces of ophiolatry in many other parts. Among the Ijaw, the cult of Tamuno, a mother-goddess, is exceptionally strong.

The researches of Basden *) (1921) are more recent than any of those described. This writer distinguishes between an act of worship and reverence for sacred objects.

*) George Thomas Basden (1873 – 1944) was Archdeacon of the Niger from 1926 until 1936.

Among the Ibos, examples of sacred objects are numerous and varied. So also are the objects offered in sacrifice. The python must be added to the list of sacred animals, which include certain fish and monkeys.

“Over the greater part, if not the whole of the Ibo country, pythons, more especially the smaller species, are sacred. These reptiles are referred to as’our mother,’ and to kill one is a grave offence.

If a man has the misfortune to kill one, he will mourn for a year, and will abstain from shaving his head. Monkeys, birds, and various animals are treated similarly in the regions where they are held to be sacred.”

If a person is injured by a sacred tree or reptile, the inference is that he has committed some offence. With the exception of the python, snakes are killed without hesitation. Those who have forsaken paganism include the python among edible meats.

West Africa undoubtedly yields evidence of python worship, especially in Dahomey and southern Nigeria. There is also supplementary evidence with regard to python cults and beliefs. Among these data must be classed a few facts relating to the beliefs of the Bavili, a people described by Dennett, who lived for some years on the Lango Coast.

The snake Ndoma

There are skins of snakes in the sacred groves. Ndoma is a black snake, which is some six to eight feet in length. The reptile is said to lift itself on its tail to strike dead any person who attempts to pass it. Ndoma appears to have some connection with ideas of moral values.

When a man is wearing the iron marriage bracelet (ngofo), he asks himself the following questions, when he meets the snake Ndoma:

“Have we eaten the flesh of any animal we have killed the same day?

“Have we pointed our knives at anyone?

“Did we know our wives on the day of rest?

“Have we looked on women in their periods?

“Have we eaten the long chili peppers, instead of the smaller

kind?”

Ndoma is the snake which causes man to reflect and reason.

Accounts of python worship

A geographical survey through the Congo, South Africa, and up the east is negative with regard to the existence of python worship.

Not until the region of Lake Victoria Nyanza is reached is there evidence of a definitely organised python worship with a sacred temple, a priesthood, and definite ritual acts including sacrifice. There appears to be no definite evidence of python worship in Cameroon, but the serpent design is often employed in wood carving and the equipment of medicine-men.

Accounts of python worship in Uganda have been supplied by Canon J. Roscoe *) who spent twenty-five years in that region. His contributions to the subject are dated 1909 and 1923.

*) John Roscoe (1861 – 1932) was a British African explorer, ethnologist and missionary who had a lively intellectual exchange with James Frazer, worked as a missionary in East Africa for 25 years.

The worship of the python

Worship of the python is confined almost entirely to one clan, in Budu, South Uganda. The temple is situated on the shore of Lake Victoria Nyanza, on the bank of the river Muzini.

The temple is a large conical hut built of poles and thatched with grass. The floor of this structure is carpeted with sweet-smelling grass. On one side of the building is the sacred place of the snake and his guardian, a woman who is required to remain celibate. Over a log and a stool, a bark cloth is stretched for the python to lie upon.

In one side of the building there is a circular hole so that the python is free to go to the banks of the river.

There the reptile feeds on goats and poultry which are tied to posts near the water. In addition to this the python is fed daily on milk from sacred cows. White clay is mixed with the milk.

The reptile lies over the wooden stool and drinks the milk which is offered in a wooden bowl held by the priestess.

The python is supposed to give success in fishing. He has power over the river and all that is in it. For this reason a special meal is given to the python before the keeper goes out to fish. The names of the python are male names.

The time of worship is at new moon. Newly married men, also the husbands of barren women, make sacrifices and requests to the python, within whose power lies the assurance of fertility.

For seven days before an act of worship no work is done in the vicinity of the temple. Beating of drums announces the beginning of the rite.

The priest attends with a following of chiefs. The priesthood is hereditary, and the chief priest is head of the system. The priest receives the gifts from the people and explains their requests to the python.

A priest, dressed in a ceremonial robe, drinks from the bowl of the python, then he takes a drink of beer. The spirit of the python goes into the medium who wriggles on the floor like a snake, uttering strange sounds and talking in a language which has to be interpreted to the worshipers.

The people stand round, while the drum is beaten, and the python delivers it’s oracle. When the medium has ended his speech, he lies in a state of coma, during which time an interpreter explains to the supplicants those things which they must do in order to realise their desires.

This ritual is repeated on each of seven successive days. When children are born as a result of supplication to the python, the parents have to bring an offering to the temple.

If this is neglected, the children will sicken and die. The keeper of the python obtains the milk from the island of Sese. Here the cows belong to the god Mukasa whose wife is a female python.

At one time the kings of Uganda sent the headmen of each district to ask the python to grant children to the royal house.

The Bahima believe that the spirits of their dead princes and princesses enter snakes. A belt of the forest Nzani is sacred to these reptiles, which are fed and protected by priests in a temple. The bodies of princes and princesses receive preservative treatment.

There is said to come from the abdomen of the corpse a python, which is reared for a time, then set free in the sacred enclosure.

The same beliefs and practices are carried out in relation to the idea of a transmigration of the souls of royalty into lions.

In the Banyankole tribe the corpse of a sister of the ruler is wrapped in bark cloth and carried to the royal burial ground. Here the same rites are enacted as in the burial of the king. The royal princess is said to be born again in the form of a python which lives in the sacred forest.

There are two unquestionable areas of python worship, namely, West Africa and a smaller region in Uganda, but there is no definite evidence of similar institutions in the great extent of country between the two centres. There are, however, usages which may be the residue of a decadent python cult.

Schweinfurth *) describes the way in which pythons are welcomed to the huts of the Dinka: “I was informed that the separate snakes are individually known to the householder, who calls them by name and treats them as domestic animals. The species which is the most common is the giant python [Python sebae. Central African rock python].

*) Georg August Schweinfurth (1836 – 1925) was a Russian-Baltic German explorer of Africa.

Others are Psammophispunctatus, Psammophis sibilans, and Ahaetuella irregularis.” Such a statement as this may indicate that python worship existed in country lying between the two main centres of python worship.

Encouragement of, and respect for pythons may be a relic of a defunct worship, or the explanation may be more simple. The pythons may be encouraged because they eat or drive away rats and other small pests.

Forms of python worship

The following factors are common to the East and West African forms of python worship:

(1) The python only, but no other snake, is selected for definite worship. This choice may be due to the impressive size of the large species of python (Plate II). The reptiles are tractable and nonpoisonous. All observers are agreed that the python rarely attacks a human being.

(2) Hut structures (temples) contain internal arrangements for feeding the reptiles.

(3) The python embodies a superhuman being, god of war, spirit of the water, patron of agriculture, or goddess of fertility.

(4) The king sends messengers and offerings. He asks for prosperity.

(5) Sacred groves are found in addition to temples.

(6) Acts of worship bring people who offer sacrifice and make

requests.

(7) Priests and priestesses are employed; the latter are wives of the python. Both dance themselves in to ecstatic trance in which they make oracular utterances which are given in a language not understood by the worshipers.

In Uganda the main ceremonies of supplication are carried out at new moon; to this I have found no parallel in the ceremonies reported from West Africa.

The Uganda ceremonies include the keeping of special cows for supplying milk to the sacred pythons. One would not expect this trait of the python-worshiping complex to appear in the coastal regions of West Africa where few, if any, cows are kept. In the Lakes Region emphasis is placed on the reincarnation of kings in pythons.

The idea of reincarnation is common in West Africa, but there is not the same insistence on the reincarnation of kings in pythons. There is, however, the idea of reincarnation of a god, which is perhaps the same generic concept as the reincarnation of a king.

There is a close agreement between the python worship of West Africa and that of Uganda. A discussion of the noticeable clustering of python-worshiping centres at two ends of a probable line of migration across Africa, is a point to be discussed in relation to the map of distributions. For the present the line of inquiry is confined to a classification of the main beliefs in connection with serpents.

Source: Serpent worship in Africa by Wilfrid Dyson Hambly. Chicago 1931. Volume Fieldiana Anthropology v.21, no. 1.

Discover more from World4 - Costume - Culture - History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.