The Castel del Monte (originally castrum Sancta Maria de Monte) is a building from the time of the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II (1194-1250) in Apulia in south-eastern Italy. The castle was built from 1240 to around 1250, but was probably never completed. In particular, the interior work was apparently not finished.

The prince Enrique de Castilla “El Senador”, son of Fernando III the Saint, King of Castilla and León, was held captive in this fortress from 1280 to 1294, when he was freed and was able to return to his kingdom.

General view of Castel del Monte, Apulia, or, as it was known in Frederick’s day, Castel Santa Maria del Monte, the most celebrated of all the Emperor’s hunting seats. It is built on a height of the Murgie Hills, some nine miles from the nearest town of Andria, in a particularly lonely situation. Until a few years ago, in the almost total absence of a proper roadway for wheeled traffic, it was a very arduous excursion to visit the castle.

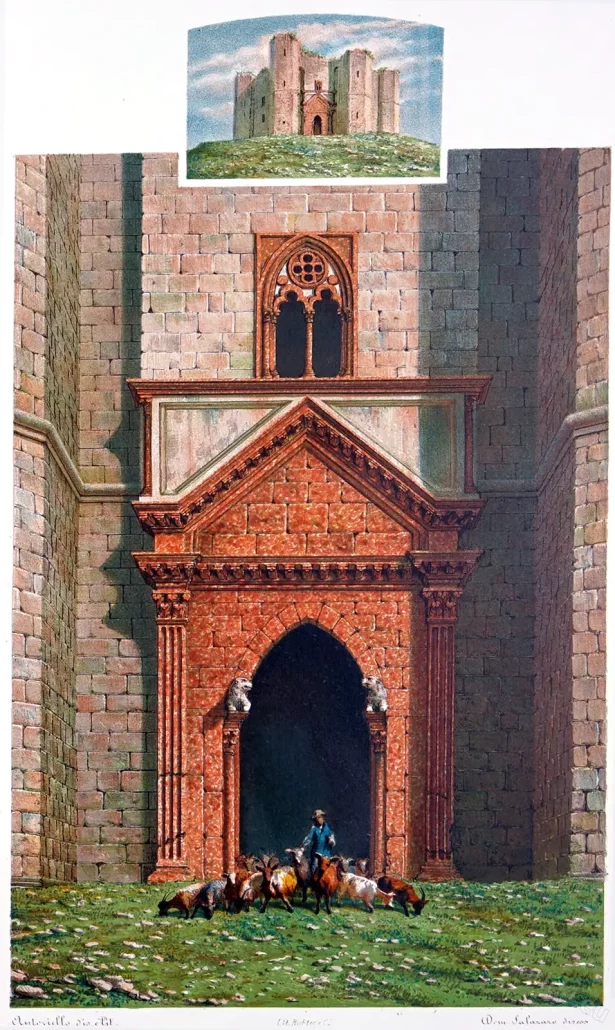

Main portal of Castel del Monte. It is all of highly polished breccia marble of a rich red. This portal is worthy of the best period of the Italian Renaissance, although antedating it by two hundred years.

An upper-floor room at Castel del Monte, the “Throne Room,” or audience chamber (see Plan, Room 3, 2nd floor). It shows the sets of triple columns supporting the Gothic vaulting. The walls of the rooms of the castle, up to the level of the horizontal molding, were formerly covered with thin sheets of highly coloured marbles, while the floors were decorated with brilliant mosaics in which red, white, blue, and gold were the predominant shades. The door and window frames are of a light orange-coloured breccia marble.

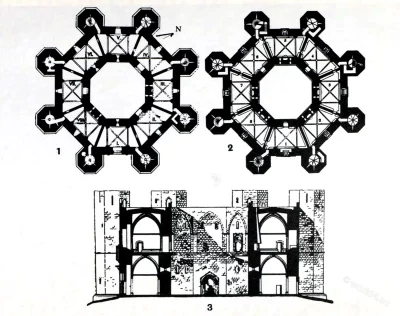

Plans and section of Castel del Monte (courtesy of Dr. Cresswell Shearer). 1. Ground-floor plan. 2. Upper-floor plan. 3. Section.

Near view of Castel del Monte, erected in 1240. The bare, stony character of the country is well seen in this picture. The masonry has suffered much from the rains and frosts of seven hundred years.

Doorway in the courtyard of Castel del Monte; above it the remains of an equestrian statue of the Emperor under a canopy or baldechino.

General view of the terrain surrounding Castel del Monte, so favourable for hawking in the Emperor’s day. It is taken from the steps of the main doorway of the castle.

Upper-floor room, Castel del Monte, with remains of a fireplace and cupboards on either side, formerly closed with metal doors-probably used to keep food warm or to dry clothing. This room is considered to have been Frederick’s bedroom. It is Room 2, second floor, see plan)

Doorway and arch of Castel del Monte. Doorway formerly giving on to the balcony that ran around the courtyard on the second-floor level. An example of the mixed architectural styles employed by the Emperor. It shows fine Gothic crotcheted capitals and moldings combined with classical acanthus foliage in the archivolt, surrounded with a band of classical laurel or bay leaves. While in general design the portal is more Roman than Gothic, the recessed well arch strongly recalls Sicilian-Norman-Saracenic influence.

Castel Del Monte

by EDWARD LEAR.

TO the south, on a spur of the hills overlooking the maritime part of the province of Basilicata and Capitanata, stands Minervino, and thither we directed our course, over undulating green meadows which descend to the plain, and we arrived about an hour before sunset at the foot of the height on which the town is situated. Minervino enjoys a noble prospect northward, over the level of Cannæ to the bay and mountain of Gargano, at which distance the outspread breadth of plain is so beautifully delicate in its infinity of clear lines, as to resemble sea more than earth.

The town is a large clean and thriving place, with several streets flanked by loggie, and altogether different in its appearance and in its population from Abruzzese or Calabrese towns. The repose, or to speak more plainly, the stagnation of the latter, contrasts very decidedly with these communities of Apulia — all bustle and animation — where well-paved streets, good houses, and strings of laden mules, proclaim an advance in commercial civilisation.

We encountered in the street Don Vincenzino Todeschi, who on reading a letter of introduction, given to us for him by Signor Manassei, seemed to consider our dwelling with him as a matter of course, and shaking hands with us heartily, begged us to go to his house and use it as our own; he was busy then, but would join us at supper … .

P—— and I are not a little perplexed as to what we shall do to-morrow, for, owing to time running short, we have but one day left ere we return towards Naples. Canosa, (ancient Cannæ) and Castel del Monte, are the two points, either of which we could be content to reach, but as each demands a hard day’s work, we finally resolve to divide them, P—— choosing Canosa, and I the old castle of Frederick Barbarossa, of which I had heard so much as one of the wonders of Apulia.

September 23. — Before daylight each of us set off on his separate journey on horseback, — P—— with the bulky Don Sebastiano to Canosa, I to the Castel del Monte, with a guardiano of Don Vincenzino’s family. Oh me! what a day of fatigue and tiresome labour! Almost immediately on leaving Minervino we came to the dullest possible country, — elevated stony plains — weariest of barren undulations stretching in unbroken ugliness towards Altamura and Gravina. Much of this hideous tract is ploughed earth, and here and there we encountered a farm house with its fountain: no distant prospect ever relieves these dismal shrubless Murgie (for so is this part of the province of Bari called), and flights of “calendroni,” with a few skylarks above, and scattered crocuses below, alone vary the sameness of the journey. At length, after nearly five hours of slow riding, we came in sight of the castle, which was the object of my journey; it is built at the edge of these plains on one of the highest, but gradually rising eminences, and looks over a prospect perfectly amazing as to its immense extent and singular character. One vast pale pink map, stretching to Monte Gargano, and the plains of Foggia, northward is at your feet; southward, Terra di Bari, and terra di Otranto, fade into the horizon; and eastward, the boundary of this extensive level is always the blue Adriatic, along which, or near its shore, you see, as in a chart, all the maritime towns of Puglia in succession, from Barletta southward towards Brindisi.

The barren stony hill from which you behold all this extraordinary outspread of plain, has upon it one solitary and remarkable building, the great hunting palace, called Castel del Monte, erected in the twelfth century by the Emperor Barbarossa, or Frederick II. Its attractions at first sight are those of position and singularity of form, which is that of an octagon, with a tower on each of the eight corners. But to an architect, the beautiful masonry and exquisite detail of the edifice (although it was never completed, and has been robbed of its fine carved-work for the purpose of ornamenting churches on the plain), render it an object of the highest curiosity and interest.

The interior of this ancient building is also extremely striking; the inner courtyard and great Gothic Hall, invested with the sombre mystery of partial decay, the eight rooms above, the numerous windows, all would repay a long visit from any one to whom the details of such architecture are desiderata.

Confining myself to making drawings of the general appearance of this celebrated castle, I had hardly time to complete two careful sketches of it, when the day was so far advanced that my guardiano recommended a speedy return, and by the time I had overcome the five hours of stony “murgie” I confess to having thoughts that any thing less interesting than Castel del Monte would hardly have compensated for the day’s labour. I reached Minervino at one hour of the night, and found P—— just arrived from his giro to Canosa.

While riding over the Murgie, slowly pacing over those stony hills, my guide indulged me with a legend of the old castle, which is worth recording, be it authentic or imaginary. The Emperor Frederick II., having resolved to build the magnificent residence on the site it now occupies, employed one of the first architects of the day to erect it; and during its progress despatched one of his courtiers to inspect the work, and to bring him a report of its character and appearance. The courtier set out; but on passing through Melfi, halted to rest at the house of a friend, where he became enamoured of a beautiful damesel, whose eyes caused him to forget Castel del Monte and his sovereign, and induced him to linger in the Norman city until a messenger arrived there charged by the Emperor to bring him immediately to the Court, then at Naples.

At that period it was by no means probable that Barbarossa, engaged in different warlike schemes, would ever have leisure to visit his new castle, and the courtier, fearful of delay, resolved to hurry into the presence and risk a description of the building which he had not seen, rather than confess his neglect of duty. Accordingly he denounced the commencement of the Castel del Monte as a total failure, both as to beauty and utility, and the architect as an impostor; on hearing which the Emperor sent immediately to the unfortunate builder, the messenger carrying an order for his disgrace, and a requisition for his instant appearance in the capital. “Suffer me to take leave of my wife and children,” said the despairing architect, and shutting himself in one of the upper rooms, he forthwith destroyed his whole family and himself, rather than fall into the hands of a monarch notorious for his severity.

The tidings of this event was, however, brought to the Emperor’s ears, and with characteristic impetuosity, he set off for Apulia directly, taking with him the first courtier-messenger, doubtless sufficiently ill at ease, from anticipations of the results about to follow his duplicity. What was Barbarossa’s indignation at beholding one of the most beautiful buildings doomed, through the falsehood of his messenger, to remain incomplete, and polluted by the blood of his most skilful subject, and that of his innocent family!

Foaming with rage, he dragged the offender by the hair of his head to the top of the highest tower, and with his own hands threw him down as a sacrifice to the memory of the architect and his family, so cruelly and wantonly destroyed.

September 24. — Having risen before sunrise, the energetic and practical Don Vincenzino gave us coffee by the aid of a spirit lamp, and we passed some hours in drawing the town of Minervino, the sparkling lights and delicate grey tints of whose buildings blended charmingly with the vast pale rosy plains of Apulia in the far distance. At nine we returned to a substantial déjeûner (lunch), and at half-past ten took leave of our thoroughly hospitable and good-natured host.

Castel Del Monte

BY HENRY SWINBURNE

AMOST disagreeable stony road brought us to Ruvo, through a vine country. The pomegranate hedges in flower, and the holme oak loaded with kermes, enlivened the prospect, which otherwise would have been very dull … . I here quitted the Roman way, and rode fifteen miles westward to Castel del Monte. The country I traversed is open, uneven and dry.

The castle is a landmark, and stands on the brow of a very high hill, the extremity of a ridge that branches out from the Apennine. The ascent to it is near half a mile long, and very steep; the view from its terrace most extensive. A vast reach of sea and plain on one side, and mountains on the other; not a city in the province but is distinguishable; yet the barrenness of the foreground takes off a great deal of the beauty of the picture.

The building is octangular, in a plain solid style; the walls are raised with reddish and white stones, ten feet six inches thick; the great gate is of marble, cut into very intricate ornaments, after the manner of the Arabians; on the balustrade of the steps lie two enormous lions of marble, their bushy manes nicely, though barbarously, expressed; the court, which is in the centre of the edifice, contains an octangular marble bason of a surprising diameter.

To carry it to the summit of such a hill must have cost an infinite zeal of labour. Two hundred steps lead up to the top of the castle, which consists of two stories. In each of them are fifteen saloons of great dimensions, cased throughout with various and valuable marbles; the ceilings are supported by triple clustered columns of a single block of white marble, the capitals extremely simple.

Various have been the opinions concerning the founder of this castle; but the best grounded ascribe it to Frederick of Swabia. I dined and spent the hot hours with great comfort under the porch, which commands a noble view of the Adriatic.

In the evening I descended the mountain, and rode nine miles to Andria, a large feudal city, east of the Roman road.

Source:

- Romantic castles and palaces as seen and described by famous writers by Esther Singleton (1865-1930, American author and journalist). New York, Dodd, 1911.

- The art of falconry: being the de arte venandi cum avibus of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, (1194-1250).

- Studi sui monumenti della Italia meridionale dal IVo al XIIIo secolo da Demetrio Salazaro. Napoli: A. Morelli, 1871.