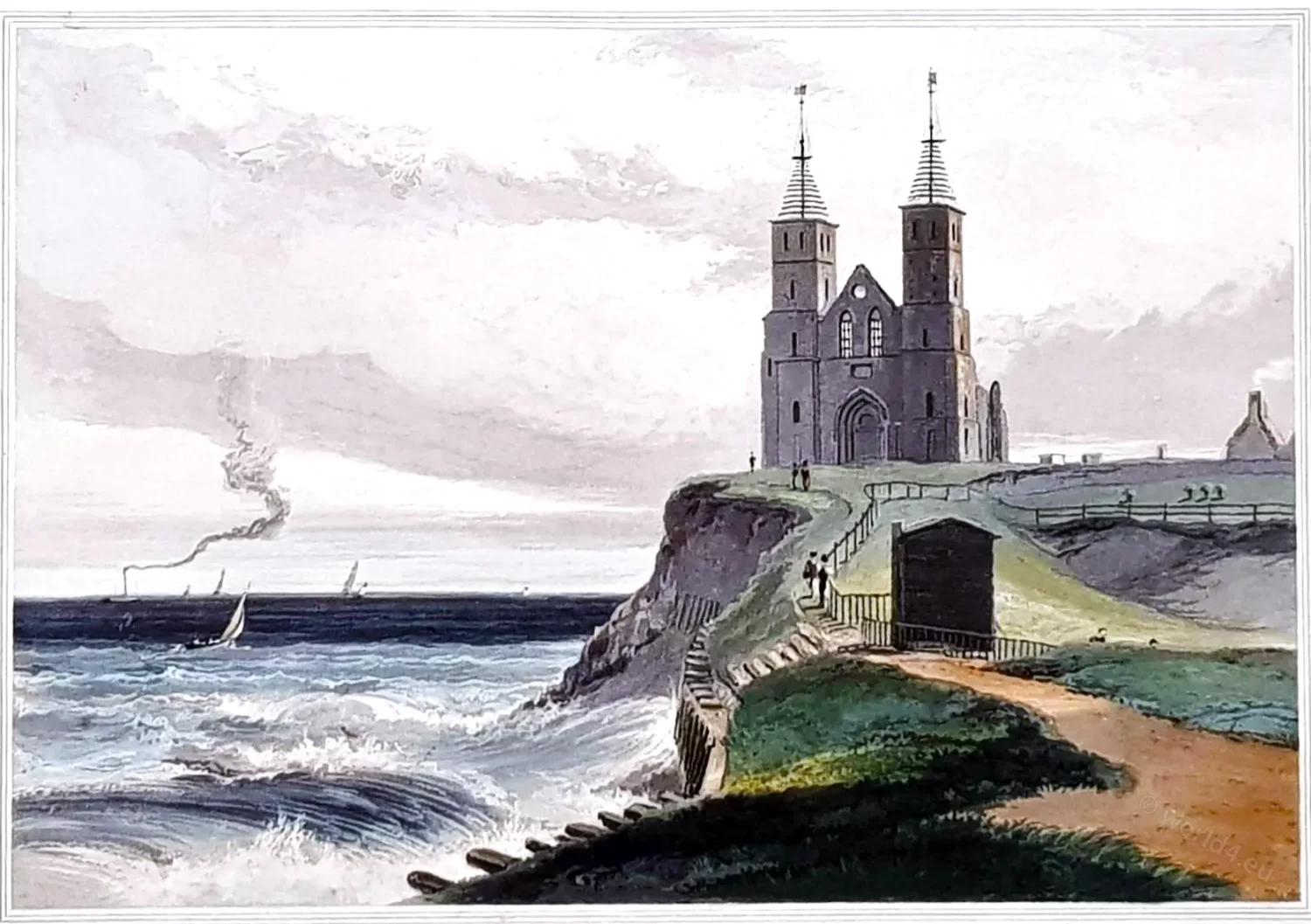

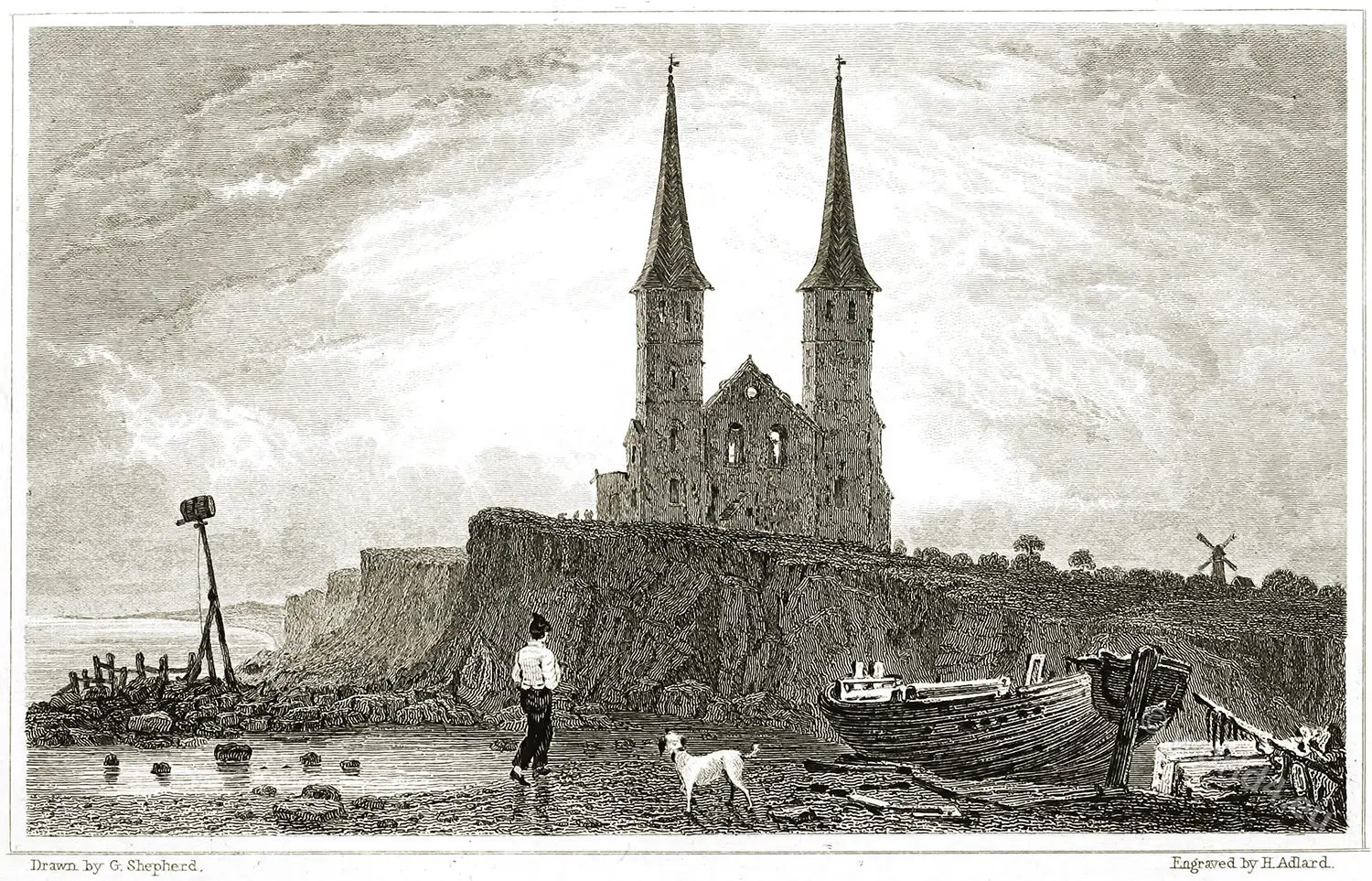

Reculver was a village – now a deserted village – about five kilometres east of Herne Bay in the English county of Kent. The village site, which included an auxiliary fort in ancient times and a monastery in the Middle Ages, was lost to the sea in the early 19th century due to coastal erosion.

Today, only the ruins of St. Mary’s Church, which was built later, can be seen at this site. The remains of the site where the village of Reculver once stood are managed by English Heritage.

THE RECULVERS.

"A heart that loved too tenderly and truly,

Will hreak at last—and in some dim sweet shade,

They'll smooth the sod o'er her you prized unduly,

And leave her to the rest for which she prayed."

Near Margate is an interesting and picturesque spot known as the Reculvers. There Caesar established a camp (Regulbium) and erected a fortress (Castrum); there the great Christian king of Kent lived and died and was buried.

But the sea, breaking in yeasty foam on rock and stone, has encroached each year upon the land, so that St. Mary’s Church, a good mile inland when Henry VIII. was king-, was gradually approached until it overhung the sea, and was finally dismantled in 1811.

Two towers of an old monastic house still serve as sea marks, and about these structures a strange tale is told, which told afresh may not be uninteresting to our readers.

Long years ago there was a worthy and valiant man, and he was blessed with two fair daughters—but in course of time the good man was dying, and his brother, the Abbot of St. Augustine, came to receive his last wishes and to impart the last consolations.

The old man commended his daughters to their uncle’s keeping, to him they were to look as to a father, adviser, and friend; in their deep grief they knew little, cared little what should happen on the morrow, all their interest was centred on their dying father, and the sands run out, and the lamp was extinguished, and the shadow of death was on the house.

The uncle did all that he had promised. To the eldest, who wished to enter the church, he rendered every assistance, and placed no obstacle in the way of the youngest, who married Henry de Belville, who was unfortunately wounded in some famous battle, and being carried to a neighbouring monastery became worse and worse, until what between the dangerous wound and the singular remedies applied, nature grew tired of the struggle and gave it up. So the youngest daughter was widowed almost as soon as she was married, and in the bitterness of her soul retired from the world and joined her sister in the cloister.

Those two sisters had loved each other from earliest infancy with more than sisterly affection. One had never smiled when the other was not merry, nor been sad but the other shed tears. Their hearts were open to each other —they lived for each other—the sorrows they had passed through together bound them more closely to each other, and now in the quiet retirement of the convent—these two sisters—whatever might be said of some of the other sisters, shut out the world, and only hoped to tread the path of life hand clasped in hand, till death should come—dark messenger of light—to summon them together to that world where sorrow never enters, and where partings are unknown.

Fourteen years had passed, and the serenity of their lives had been undisturbed. My Lady Frances, the eldest sister, had been elected Abbess of the convent, but nothing could change her affection for her sister Isabella, they were the same to each other as they had ever been. One day, however, there was a gloom seen on every face, as they assembled round the board of the refectory—and it was whispered that the Abbess had fallen sick, and that sister Isabella was distraught with grief. And in the little chamber where the Abbess, distracted with pain and weariness, lay on her hard pallet, sister Isabella wept and prayed.

What would she not do if her sister was restored, if the fever abated, if the impending stroke was spared; her sister—for her sake—struggled hard to live, and together they vowed, that if restored to health, they would make a costly offering at St. Mary’s shrine at Broadstairs.

After the lapse of a few hours, a favourable change took place : in two or three days the Abbess was able to leave her bed, in two or three more to appear in the chapel, and then both sisters took ship to make their pilgrimage and perform their vow.

That night a frightful storm arose, it prevailed all along the coast, and many a good ship went down before the morning. The vessel in which the sisters had taken passage was among the number wrecked. Some of the passengers escaped in boats. The Abbess in an insensible state was rescued in this manner, and was safely landed, but in the confusion, the Lady Isabella was forgotten, and when the Abbess opened her eyes and called upon her sister’s name there was no voice to answer. Two strong fellows, touched by her grief, returned to the drifting wreck, and brought away—oh joy unspeakable—her sister still alive; she clasped her in her arms again, and saw her die

The Abbess performed her vow alone. On her return to the place of the wreck, she restored the church where Isabella was interred. The twin towers looked out upon the sea, and beneath their shadow the Abbess and Nun united again in death—sleep soundly.

Source: Beauties of English scenery: illustrated with thirty-five engravings on steel, from designs by William Henry Bartlett, D. Cox, W. Daniell, R.A., H. Gastineau, C. Bentley, G. Shepherd, T. M. Baynes, &c. by John Tillotson (ca. 1830-1871). London: Allman & Co. 1860.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.