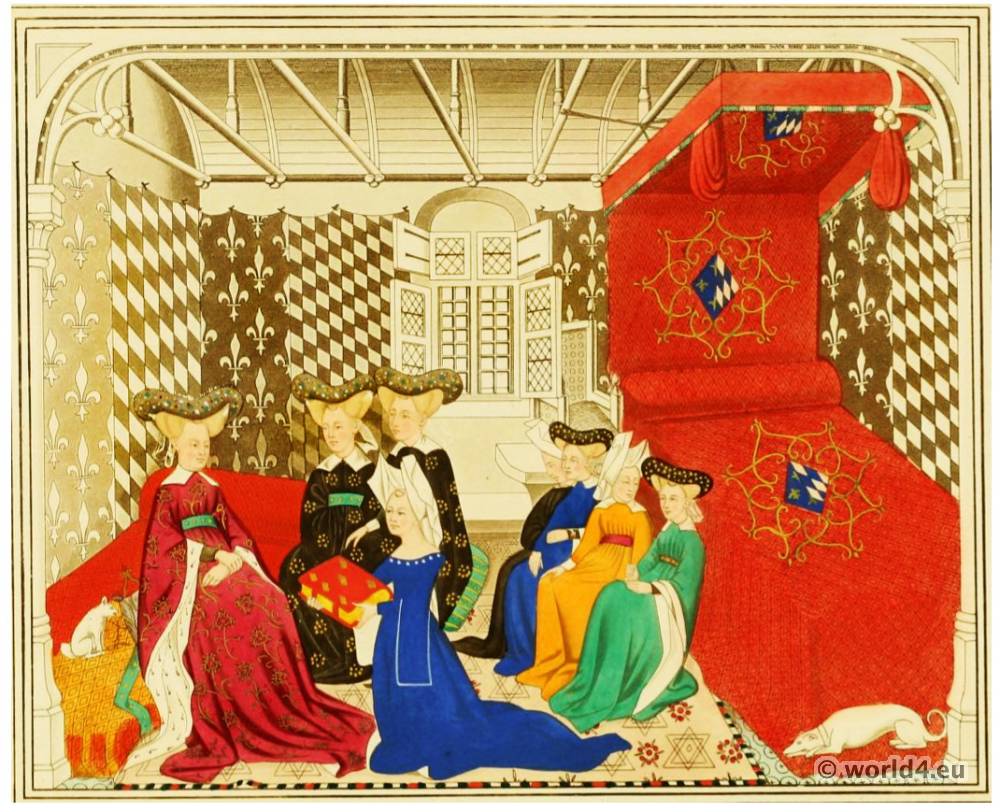

Christine de Pizan presenting her manuscript against the Roman de la Rose to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, France c. 1410 – c. 1414.

THE accompanying plate is taken from MS. Harleian No. 6431, a splendid volume, written in the earlier years of the fifteenth century, filled with illuminations, and containing a large collection of the writings in prose and verse of Christine de Pisan.

The illumination represented in our plate is a remarkably interesting representation of the interior of a room in a royal palace of the beginning of the fifteenth century; the ceiling supported by elegant rafters of wood, the couch (of which we have few specimens at this early period), the carpet thrown over the floor, and several other articles, are worthy of notice.

But the picture is valuable in another point of view: it contains portraits of two celebrated women, Christine de Pisan, the poetess, and Isabelle of Bavaria, the queen of France, to whom Christine is represented as presenting this identical volume. It is somewhat remarkable, that the compiler of the Harleian Catalogue represents it as doubtful for whom the book was made; the first poem, to which this picture forms the illustration, is addressed to the queen:

“Le corps enelin vers vous m’adresce,

En saluant par grant humblece,

Pry Dieu qu’il vous tiengne en souffranee

Lone temps vive, et après l’oultrance

De la mort vous doint la richece

De Paradis, qui point ne cesse.

* * * * * * * *

Haulte dame, en qui sont tous biens,

Et ma tressouverainne, je viens

Vers vous comme vo creature,

Pour ce livre ey que je tiens

Vous presenter, où il n’a riens

En histoire n’en escripture,

Que n’aye en ma pensée pure

Pris ou stile que je detiens,

Du seul sentement que retiens

Des dons de Dieu et de nature;

Quoy que mainte aultre creature

En ait plus en fait et maintiens.

Et sont ou volume compris

Plusieurs livres, esquieulx j’ay pris

A parler en maintes manières

Differens, et pour ce l’empris,

Que on en devient plus appris

D’oyr de diverges matieres.”

After more verses of this kind, Christine proceeds to say that, since she had received the queen’s order to make the volume for her, she had caused it to be written, chaptered (i. e. adorned with initials), and illuminated, in the best manner in her power:

“Si l’ay fait, ma dame, ordener,

Depuis que je seeus que assener

Le devoye à vous, si que ay seeu,

Tout au mieulx, et le parfiner,

Descapre, et bien enluminer,

Dès que vo command en receu,” etc.

Christine de Pisan was one of the most remarkable women of her time. She was the daughter of Thomas de Pisan, a famous scholar of Bologna, who, in 1368, when his daughter was five years of age, went to Paris at the invitation of Charles V. (1338-1380 Charles V, called the Wise was from 1364 to 1380 King of France. He was the third king of the House of Valois, a side branch of the Capetian, and is considered one of the great kings of the French Middle Ages.) who made him his astrologer.

Thomas de Pisan was made rich by the munificence of his royal patron, and Christine, greedy of learning like her father, was educated with care, and became herself celebrated as one of the most learned ladies of the age in which she lived. She married a gentleman of Picardy, named Étienne du Castel (1354–1390), whom the king immediately appointed one of his notaries and secretaries. But the prosperity of this accomplished family was destined to be suddenly cut short.

Charles V. died in 1380; the pension of Thomas de Pisan ended with the life of his patron, and, reduced to comparative poverty, he died broken-hearted; and Stephen Castel was, after a few years, carried off by a contagious disease. Christine was thus left a widow, in poverty, with three children depending upon her for their support.

From this time she dedicated herself to literary compositions, and by the fertility of her talent obtained patrons and protectors. Thus Christine, when she had retired from the world personally (for she had sought tranquillity in a convent), was brought before it more directly by her writings. She was thrown on troubled and dangerous times, and, though a woman, she did not hesitate to employ her talent in the controversies which then tore her adopted country.

On one side she took an active part with the celebrated chancellor Gerson (Jean le Charlier de Gerson 1363-1429 was a French theologian, mystic and chancellor of the Sorbonne in Paris.) in writing against the Roman de la Rose; while on the other, by her political treatises, she attempted to arrest the storm which was breaking over France in the earlier part of the fifteenth century. If she was not successful in her efforts, she nevertheless merited the gratitude of her contemporaries, and the admiration of future times. She looked forward in hope to better times, and lived at least to see them mend: both Gerson and Christine welcomed by their writings the appearance of the Maid of Orleans.

The writings of Christine are extremely numerous, both in prose and verse, and are historically of great importance. It is to be hoped that the zeal of our continental neighbours for their early literature will lead to their publication. A clever and interesting publication, by M. Thomassy, entitled Essai sur les Ecrits politiques de Christine de Pisan, suivi d’une notice littéraire et de Pièces inédites, has already paved the way. The manuscripts are tolerably numerous.

The initial letter on the preceding page is taken from the same volume which furnished the illumination.

In the French literary history Christine de Pizan was treated for a long time rather neglected, but today it is regarded as by far the most prolific and versatile of all writers of her generation. Literary and social scientists appreciate them also as a woman’s rights activist avant la lettre.

Her’s today most famous work is Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Women). Following the Epitre au Dieu d’Amour (Epistle to the God of Love) by Christine de Pizan to 1399 inflamed also the first known literary controversy in France or in Paris. Herein Christine criticized the negative comments made by Jean de Meung in the Rose novel (Le Roman de la Rose) is authored in the 13th century verse novel about love and is considered the most successful and influential of medieval French literature) about women and love.

As particularly hostile to women she denounces his dramatic and cynical representation of physical love. Christine herself also referred again to the position Dit [poem =] de la rose (1402) in which she portrays the fictional creation of a women protective “Orders of the Rose”.

Source: Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages from the 7th to the 17th centuries by Henry Shaw F.S.A. Published: London William Pickering 1843.

Continuing