Amboise (after the stream name Ambacia, today Amasse) was a fortress of the Gauls that was taken over by the Romans. In 503, Clovis I (King of the Franks) and Alaric II (King of the Goths) signed a peace agreement here.

AMBOISE, INDRE-ET-LOIRE.*

by Theodore Andrea Cook.

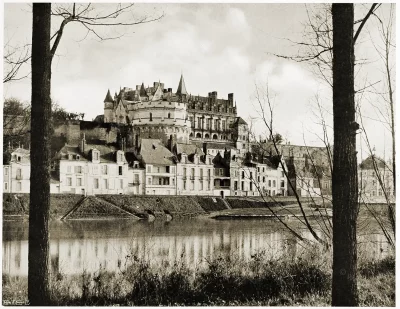

AMBOISE is the only castle in France, as far as our present knowledge goes, which has had the honour of being sketched by Leonardo da Vinci, and though his pen-and-ink drawing of it in the Windsor collection is not a more faithful representation of architecture than was Turner’s vision of Château Gaillard reproduced in previous pages, no one who knows how to treat a Leonardo manuscript can fail to recognise its authenticity.

When looked at in a mirror (as all the great Italian’s handwriting must be read) the round tower that is Amboise’s chief feature stands in its right place, and you find that Leonardo’s first impression of the castle is very much your own as it breaks on you from the bridge across the river.

AMBOISE.

A Seat of the Duc d’Orleans.

It is, therefore, with Leonardo, and with one other famous visitor to that gallery above the arches which Leonardo drew, that I shall chiefly deal in this short sketch of a place that has been so often described before in every detail of its long and varied history from Vercingétorix to Abd-el-Kader. That other visitor upon the rusted gallery was Mary Queen of Scots, and between her death and the birth of Leonardo you may find all that is greatest in the story of Amboise.

I know few places that still preserve so well the double character of a royal fortress the domination of its surroundings, the imposing of its strength and splendour on the town and river underneath, and, on the other hand, the remote and special quality of guarded isolation which rests upon the quiet terraces of its uplifted garden, terraces that breathe a higher air, a more reserved and prouder charm than can be felt beneath the pinnacles and buttresses that fence it in.

It stands like some Gothic Acropolis above a smaller Athens and a wider stream ; and it is built, with that gorgeous eye for situations which the older masons cultivated, upon high ground that looks higher than it actually is because the stonework rises from the lowest levels to the topmost platform, and completely commands the approaches of the noble bridge across the Loire.

The castle is now a kind of lordly refuge for the poorer dependants of the House of Orléans, and there is little left within it to recall the work of those Italian artists whom Charles VIII brought back with him from Italy. But neither time nor man has yet been able to ruin the massive exterior which had mainly risen before his reign, and which both he and Louis XII still further decorated. It was the playground of the youth of Francis I, and he cared little for it after he had grown to man’s estate.

Chambord is the measure of his taste, and Blois the test of his French workmen’s aptitude. The relatively small portion of sixteenth century Amboise, which is still standing, remains very much as Francis II and his young Queen saw it, and the only restoration possible has been the necessary strengthening of a fabric that was nearly destroyed in the Franco-German War.

One of the vast round towers, its special pride, has, for instance, received an obviously new set of battlements after the model of Pierrefonds. But the main lines of the massive masonry remain untouched; and though the façade that fronts the river has a fine effect of rich decoration, the inner courtyard is almost coldly bare.

It is the garden and the terraces that make the buildings of Amboise still beautiful—these, and the exquisite jewel of its chapel, reared on tall shafts of stone like an expanding lily on its rising stalk.

This chapel is probably the first thing that will be discovered by the visitor who wanders through the lower entrance and climbs gradually up towards the higher ground. From the level of its entrance it seems but a small and delicate fragment. Yet from without the castle walls it is one of the main features of the buildings’ outlines.

Above its doorway is set the sculptured story of St. Hubert and the miraculous stag, together with the legend of St. Christopher and of St. Anthony in the desert, the latter on the spectator’s left. The mixture of three such entirely different subjects on the same panel is characteristic rather of French Gothic than of Italian workmanship, and if it must be attributed to a foreigner, there is more probability in thinking it was a Flemish hand to which we owe it. But the carvings inside are more Italian both in taste and execution, especially the grotesque figure of the ape above the altar, which was selected by Champfleury as a typical illustration of that age and country. This detailed work was probably all finished in the reign of Louis XII.

Italian taste most certainly presided over the gardens, for they were laid out by Pacello da Mercogliano, the Neapolitan. But his treeless parterre of varied “knots” surrounded by colonnaded loggias is not easily recognisable in the broad walks and shady avenues of clipped trees—very much like the famous avenue in Trinity Gardens at Oxford—which are the delight of every visitor. It is not in architecture alone that the Italians impressed their memory on the Valley of the Loire. Two of the former patrons of Leonardo were known there before his own arrival— Ludovico Sforza, called II Moro, and Caesar Borgia.

After taking Bayard prisoner at Milan, only to set him free again, Ludovico had been betrayed to La Trémouille by his Swiss mercenaries, and was sent to the dungeons of Loches, where he languished for nine years in a sunless subterranean cavern before he died.

The pitiful frescoes and inscriptions he left in his cell by the banks of the Indre were still fresh when Leonardo drew the great towers of Amboise across the Loire, not very far off.

SCULPTURE OVER CHAPEL ENTRANCE.

The Story of St. Hubert and the miraculous Stag, with the legend of St. Christopher and St. Anthony in the Desert.

At Blois, on the same stream, at Chinon, on the Vienne, the recollection of Caesar Borgia can have been scarcely less vivid in the minds of the inhabitants; for it was at Blois that Caesar, who was created Duc de Valentinois as a reward for the Papal consent to Louis XII’s divorce, had been himself married to Charlotte d’Albret. The French King had made his triumphal entry into Milan with his new ally in October, 1499, and saw there for the first time the fresco of the Last Supper and the equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza.

Though it is by the former of these masterpieces that Leonardo’s fame has gained its greatest modern expansion, it was his work upon the statue that most deeply impressed his genius upon his countrymen.

The project for it was as old as 1472, but for many years “non era un Lionardo ancor trovato,” *) as Baldassare Taccone said when the model by Da Vinci was first set up in 1493 in the court of the castle of the Visconti, when Bianca Maria Sforza was married to the Emperor Maximilian.

*) “was not a Lionardo yet found”.

It was never cast in bronze, because its sculptor insisted on attempting it in one piece, and sufficient money was never forthcoming from the Duke’s exchequer for the purpose, or even for his artists’ salaries.

There is every probability that the model seen by Louis XII was partially destroyed when his restraining hand was no longer over his soldiers and they occupied Milan after the battle of Novara in April, 1500. “I cannot speak of it without grief and indignation,” writes Fra Sabba di Castiglione; “so noble and masterly a work made a target by the Gascon bowmen.” Enough was left for the Duke of Ferrara to ask the Cardinal d’Amboise for a cast of what, even then, was “daily perishing.” But Louis XII would not accord permission.

We have, therefore, nothing save a few sketches in Leonardo’s manuscripts that can recall a work which was more highly praised during its brief existence than any other single work of the Renaissance. And of its artist’s other sculptures we know even less.

The Duke had fled from the law when Louis XII entered the city. In April Leonardo wrote: The Duke has lost his state, his possessions and his liberty, and not one of his works has been completed. The disappointment conveyed in the last few words is perhaps the reason for the cold impassiveness of the first sentence. The artist moved on to Mantua, Venice and Florence, where his Madonna with St. Anne was the admiration of the populace.

But by the autumn of 1501, with a mind that ever shifted from sculpture to painting, from biology to architecture, from mathematics to engineering, Leonardo was inspecting the fortresses of Romagna for Cæsar Borgia.

Of that journey he has left notes concerning the dovecote and the palace steps of Urbino, the bell of Siena, the library of Pesaro, the harmony of falling water in the fountain of Rimini, the breaking of the waves upon the shore of Piombino, the bastions for the tower of Porto Cesenatico, the contour of the ground in Central Italy. In 1503 he was in fresh service, studying for the Signoria of Florence how to divert the course of the Arno and thus cut off Pisa from the sea. Soon afterwards he was at work on the Battle of Anghiari, the third great commission of his life.

Again his passion for experimenting robbed the world of yet another masterpiece. His work upon it was, indeed, interrupted by a summons to Milan from the Cardinal d’Amboise and Louis XII, who speaks of him as “our dear and well-beloved Léonard da Vincy, our painter and engineer in ordinary,” and by the death of his father, Piero. But the Battle of Anghiari remained a fragment which soon disappeared, and the cartoon itself is lost. Its artist’s mind had once more been directed in other channels.

The triumphal entry of Louis XII into Milan in 1509 was graced with an “automatic lion ” designed by Leonardo, whose praises still echo in the verses of the French Court poets.

After the death of Gaston de Foix at Ravenna in 1512, Maximilian Sforza, strong in the support of Spain, the Pope and Venice, re-entered Milan. Leonardo shows his customary indifference to these political catastrophes; but his work for Italian Princes was evidently over. His sympathies had been too publicly in favour of the French invader.

He first sought, in these circumstances, for the patronage of the Pope, Giovanni de’ Medici; and Melzi accompanied him in 1513 to Rome, where he worked in the Belvedere, and no doubt painted “the portrait of a lady of Florence executed by request of the late Julian de’ Medici, the Magnificent,” which was seen at Cloux, near Amboise, in 1517, by Antonio de Beatis, secretary to the Cardinal of Aragon.

The reason for its presence there was that in December, 1516, Leonardo had been attending the Concordat held in Bologna between the Pope and Francis I, and that when the French King returned home, a month afterwards, Leonardo went with him. The artist had definitely thrown in his lot with France. He came to the Valley of the Loire to die, and close to Amboise he breathed his last.

The official salary allotted to Leonardo da Vinci, the “premier peintre et ingénieur et architecte du Roy, mechanischien d’estat,” was about one thousand four hundred pounds, and he was given a residence at the little manor house of Cloux, near Amboise. Of the courtyard and entrance, with its soft warm brickwork and cream-coloured mouldings, Mr. Frederick Evans has made a photograph for these pages, and no traveller in the Loire Valley should omit to visit one of the few places now left where Leonardo is known to have lived for some time. It was built for Le Loup, maitre d’hôtel to Louis XI.

We may imagine that the old man passed most of his days in his studio, but his mind remained to the end more active than his body, and there are traces of many various projects in which he was engaged, such as the festivities at the Dauphin’s birth and christening and the wedding of the Duke of Urbino, or the planning of a canal, with locks near Romorantin, that was to join the Loire and the Saône and thus provide a highway by water from Italy to the northern centres of France. Sketches have survived, too, for a great pleasure-palace and water-gardens that would have involved the destruction of much of the Amboise we know.

Amid all this the pictures which are Leonardo’s noblest claim to immortality to-day took the same secondary place in his activities which they seem to have done throughout his strenuous life of discovery and research. But among the many illustrious visitors who must have come to Cloux between 1516 and 1519, one at least has left on record the paintings which he saw. In October, 1517, the Cardinal of Aragon visited Leonardo, and his secretary describes the picture of the Florentine lady already mentioned, a second of the young John the Baptist, which was probably that now in the Louvre, and a third of the Madonna and Child in the lap of St. Anne, “all three perfect.” They had probably all been brought with him from Rome and Florence.

The secretary also notices that “a certain paralysis has attacked his right hand which forbids the expecting of any more good work from him”; but Leonardo was left-handed, and always wrote very badly with his right hand, as may be seen from the manuscripts. His drawings are invariably shaded from left to right, for the same reason, and the writing of his notes goes from the right-hand end of the line towards the left of the page, so that they have to be read in a mirror. This also was because he wrote with his left hand, as his friend, Fra Luca Pacioli, definitely states.

Considering the few pictures we hear of at Cloux, it is probable that the priceless collection of manuscripts was the most valuable of his possessions there ; certainly it is the last place in which we know that they were all together, and those on anatomy, on the nature of water and on various machines, his visitors saw “ in an endless number of volumes which will be profitable and very delectable.” I have examined a large number of them, and possess several hundred photographs of the drawings and diagrams they contain.

Apart from this portion, which is perhaps the most valuable, as it is certainly the most lovely, the papers are very much like the notes that might be made by a very exceptional professor for a course of very extraordinary lectures. Their literary construction lags far behind the ardour for discovery that inspired them. They remained almost as unknown to Leonardo’s contemporaries and immediate successors as he was himself in the last years of his life.

In many cases they were either lost or concealed for centuries, with the curious result that the laws which he established or divined have been in that long interval of oblivion rediscovered independently and proved more clearly by advancing knowledge. So that, though many discoveries had to be ante-dated, when the manuscripts at last came to light, the reputation of his successors remains as bright as it had been before.

We think no less of Lyell because it is now known that, centuries before Lyell’s theories of the age of the earth were published, Leonardo had calculated two hundred thousand years for the accumulations at the mouth of the Po, and had explained the meaning of the strata in the Apennines revealed by the cutting of the river Lamona. His method was to penetrate the secret hiding-places of truth with a passionate industry that never shrank from toil, that has been paralleled by few save Darwin.

His anatomical drawings, apart from their exquisite draughtsmanship, contain so many keen parallels and suggestive indications that the author of The Origin of Species would have perused them with delight. His studies of trees and plants and clouds would have enchanted the writer of Modern Painters. But, as far as we are aware, neither Darwin nor Ruskin had ever seen these manuscripts.

I might follow out the same line of thought in many details: Leonardo suggested the theory of the eye which was slowly elaborated by Kepler and by Helmholtz afterwards. “II moto,” wrote the Italian, “é causa d’ogni vita.” “Activity,” said Professor Clifford, four hundred years later, “is the first condition of development.” It was Leonardo who first proposed the division of animals into vertebrates and invertebrates, and first guessed the circulation of the blood without having discovered its actual mechanism. It was he who first explained the presence of fossil shells upon the arid mountain-tops as due to the action of water, “Nature’s charioteer,” which left these traces of living organisms behind her in the dawn of a far older world.

He anticipated Cuvier with the proof that the floor of the ocean is continually rising, sometimes rapidly, sometimes with almost inappreciable slowness. If he may be said to have founded the scientific study of anatomy by means of dissection, he certainly was the first to investigate the structural classification of plants—to enunciate the botanical laws of phyllotaxis. He even anticipated Copernicus by the assertion, “Il sole non si move.” He laid down the principles of those laws of the movement and equilibrium of fluids which were completed by Pascal, D’Alembert and others.

He designed a breech-loading cannon which propelled its ball by steam, and invented paddle-wheels for boats. He studied the flights of birds with extraordinary accuracy, and suggested the use of parachutes and of screws on a vertical axis as a means of aerial locomotion. No wonder that Cellini heard King Francis say, “He did not believe that any other man had come into the world who had attained so great a knowledge as Leonardo, and that not only as sculptor, painter and architect, but as a profound philosopher as well.”

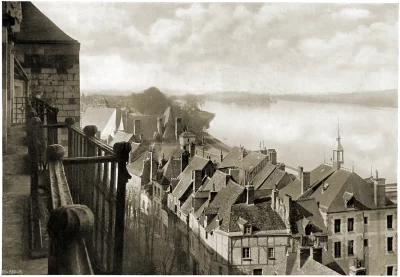

UPPER BALCONY OF THE TOUR DE CESAR.

Showing the Railing, on Spikes of which the Heads of the massacred Huguenots were stuck.

The King may have thought so once, but he must have easily forgotten it. It is not even metaphorically true that Leonardo died in the arms of Francis, except in so far that the artist’s last lodging upon earth had been provided by the King. But no provision seems to have been made for the interment of all that was mortal of the greatest thinker of his own or any age.

The modern bust in the gardens of Amboise is his only memorial there, and it stands above some ashes that may or may not be Leonardo’s. For though the Italian had left instructions to be interred in the church of St. Florentin in the castle of Amboise, no one remembered he was buried there when it was destroyed by Ducos in 1808. When M. Arsène Houssaye dug through the ruins in 1854, he found a skull.

“The wide high forehead hung over the eyes. The occipital arc was ample and pure.” But no one can tell whether it was Leonardo s. At Cloux M. Houssaye also found two stones marked with the letters “LEO . . . INC . .” They are the sole memorials likely to be contemporary. He died on May 2nd, 1519, and to his beloved pupil and companion, Francesco Melzi, he bequeathed all his manuscripts and personal effects before he “lay down happily to die as one who slept happy after a long day’s toil.”

Very different is the character and personality of the next outstanding heroine whom I have chosen as typical of the story of Amboise. In November, 1559, just forty years after Leonardo’s death, Mary Stuart was riding into Amboise beside her young husband, Francis II, and all the town turned out to cheer her. In March she was looking down, from that rusted iron balcony which crosses the great façade of the castle above the river, upon a scene of carnage that was rarely paralleled even in those days of ruthless massacre. The Loire rolled thick with corpses. The château itself and all its woods were crammed with dead. The gallows and the scaffold never ceased their hideous work. The whole place reeked like a shambles.

The Guises, fairly maddened with blood, had crushed the ill-fated conspiracy of the Huguenots under La Renaudie by wholesale slaughter; and Catherine de’ Medici was looking on, with Mary Stuart and the whole French Court. Those who forget that Mary Queen of Scots was the daughter not only of James V, but of Mary of Lorraine, and that she was not yet eighteen when, as Queen of France, she saw such scenes as the massacre of Amboise, will never be able rightly to appreciate the years that followed in the life of a woman who expiated her shortcomings to the full and met her death upon the block, as she had faced her life throughout, with noble courage and unshaken resolution.

The exquisite crayon sketch of her, made just at the time she was in Amboise, by Clouet (or, as some think, by Jean de Court) shows “the bald expanse of brow” that, in those times, was fashionable; but above it is the reddish brown hair of her girlhood, delicately “crimped.” Her eyebrows, not too close together, show a thin, pencilled arch. Her eyes are reddish brown, somewhat long and narrow; her nose is long and low and straight. She looks too prim and staid for the creature of infinitely changeful moods we know, for the woman who flashed so readily from laughter into tears and back again.

But there is no sly, foxy look about her; no hunted expression in the defiant eyes of one who fights for life. “Espiègle,” Balzac calls her; and we may well believe it. But there was a dazzling pallor in her complexion, a curious haunting charm in the small mouth, the prettily rounded chin, the graceful oval of the face; a promise of vivacity and passion behind the seemliness and quiet of a Queen.

Mary was but six when in 1548 she set sail for France as the betrothed of the Dauphin. Of the society in which she lived for the next thirteen years Brantôme is the Petronius. Compared to it the Court of Charles II sounds like the Court of Queen Victoria. Its jests were murder and debauchery.

The policy of its leader was based on the corruption of her children; and to the feeblest of that poisonous brood Mary was married in 1558, six months before Elizabeth ascended the throne of England. By the counsel of the Guises their niece bore the arms of England as well as those of France and Scotland. It was an inauspicious start.

You may imagine the men and women among whom that young Queen lived her life, the escadron volant of Catherine de’ Medici, the mignons of the future Henri III, the men who were to be the assassins of St. Bartholomew. In the midst of them, her sickly husband, with his pale little puffy face and flat nose, stands beside the Queen Mother, the strong, intelligent, ruthless Florentine with the true muzzle of the Medici that became the underhanging jowl of her old age. In 1554, when scarcely twelve, with pretty Miss Fleming at her side, Mary made her first entrance on this sinister stage at a fête in the gardens of St. Germain.

Already she showed an astonishing acquaintance with books, affairs and men. In a very few years she was surrounded by a little court of poets, Du Bellay, Ronsard and De Maison Fleur among them. As Dauphine and as Queen her influence in France was even greater than her enemies imagined; and a romantic memory of her youthful beauty, a tender pity for her later sorrows never faded in a land where she was Queen for so short a time. “All the world wondered,” wrote Giovanni Correro, “to see a girl so delicately nurtured and so little used to government able to resist the influences against her. But her joy was short-lived. At one blow she lost her husband, her freedom, and her crown.”

Those who criticise the actions of Mary as a Queen, in the troubled years when she was fighting for her crown in Scotland, forget sometimes that she was also a woman as passionate as she was brave.

In 1568, at Carlisle, Sir Francis Knollys wrote the best description and the noblest panegyric extant of the Queen of Scots. He noticed particularly her indifference to form and ceremony, her daring grace and openness of manner, her frank love of revenge, her readiness to face any peril in the hope of victory, her intense delight in courage, which she praised in her enemies as keenly as she deplored the lack of it in any of her friends. Her loyalty was equally indomitable, as she showed after her arrest at Tixall Park, when she cheered the wife of her English secretary with promises to answer for every accusation brought against him, even with baptising his new-born child in her own name and with her own hands. In her will the same keynote is struck. Not a friend is forgotten, and every enemy is remembered. Her mind was as implacable to the one as it was faithful to the other.

If her courage was rare, her intelligence was just as brilliant. No kinder friend could be desired, no enemy more deadly could be dreaded. “Passion alone could shake the double fortress of her impregnable heart and ever active brain,” wrote Swinburne, in the finest biographical study he ever penned. “Of repentance it would seem that she knew as little as of fear, having been trained from her infancy in a religion where the Decalogue was supplanted by the Creed.”

In that atmosphere it is no wonder that she learnt the most delicate acts of dissimulation; it is extraordinary that she ever preferred daring to subtlety, or that beyond the voluptuous or intellectual charms of her beauty or her culture she preserved the fresher charm of a simplicity as frank as it was fearless.

In patriotism alone she was inferior to Elizabeth, and by that alone was she defeated; for much as Elizabeth loved herself, she yet loved England more, and against that irresistible strength of national emotion even the qualities which made Mary Queen of Scots so unparalleled a friend and leader were of no avail.

To me the two figures of Leonardo and of Mary are always evoked by the Italian gardens and the proud battlements of Amboise.

Beneath the trees I see the stately figure of the one, his head bowed on a delicate hand, thinking his last over the projects that were to outlive him for so long. Upon the gallery and above the huge round towers, the Tour de César and the Tour des Minimes, I see the brilliant white face of the Queen of Scots beneath her red-brown hair, facing the Huguenot massacres as she faced her own fate—unflinching, steadfast. It is almost the last fair thing the towers of Amboise have beheld.

Up those vast inclined planes within the Tour des Minimes the Emperor had ridden on horseback as the guest of Francis. They were the slow, sad thoroughfare of many a prisoner after Mary Stuart had left France. Here were shut up César de Vendôme and his brother Alexandre, sons of Gabrielle d’Estrées. Here wandered the banished Duc de Choiseul. Under the Revolution it became a prison, and its estate was little bettered when Napoleon gave it to his vandal colleague in the consulate, Roger Ducos.

The last of its prisoners was Abd-el-Kader. Finally it passed back to the Orleans family, in whose hands it remains to this day, as the hospice for their old retainers. The beauties of its interior have passed away for ever; but the splendour of its site can never be taken from it while one stone remains upon another.

La Fontaine thought the view from its battlements one of the most beautiful he ever looked upon. And from them you may still look out upon that valley where Plantagenets have bled and died, where the Black Prince’s troops have pillaged up and down the river, where Sir Walter Raleigh served his first campaign, in that broad, sunlit landscape.

Where from the frequent bridge

Like emblems of infinity

The trenched waters run from sky to sky.

Source: Twenty Five Great Houses Of France by Theodore Andrea Cook (British art critic and writer), 1916.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.