" ….. flutes In Dervish hands at mystic dance, Whose hopes or fears, loves, joys, or cares, Are whispered in ecstatic trance." IZZET MOLLA, The Reed-pen's Reply.

"Stone about its waist begirdled, and with iron staff in hand, Tremblingly the compass-needle seeketh for the Loved One's Land." JĀMĪ.

The Dervishes of the various Orders.

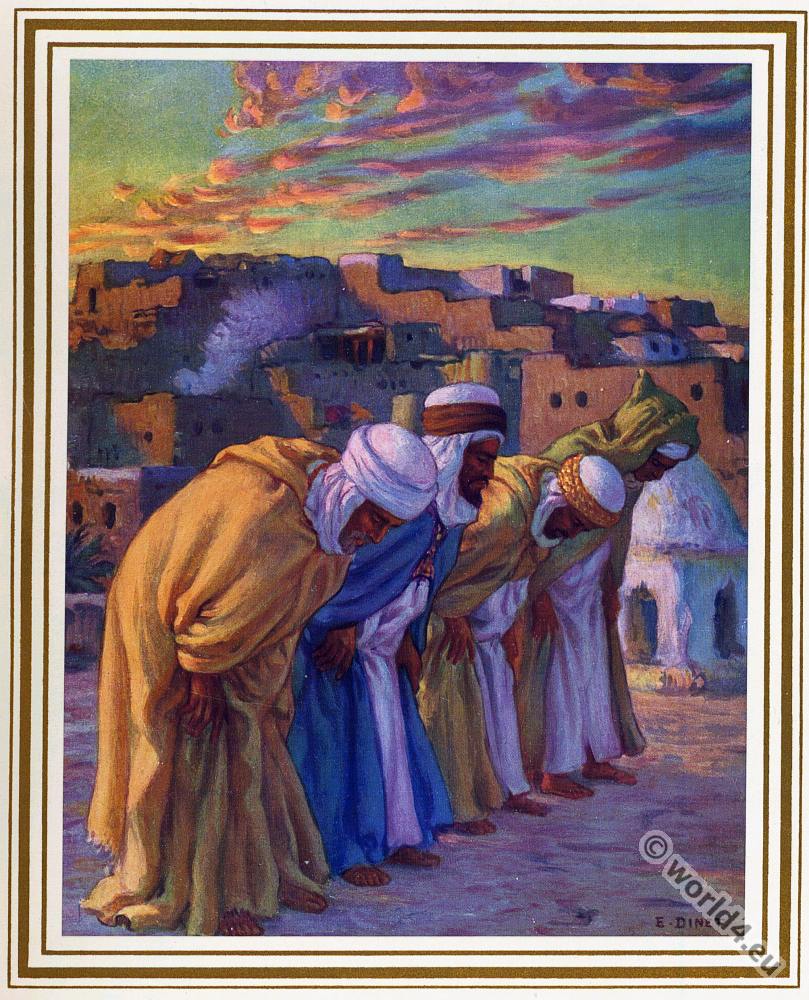

Islamic mysticism.

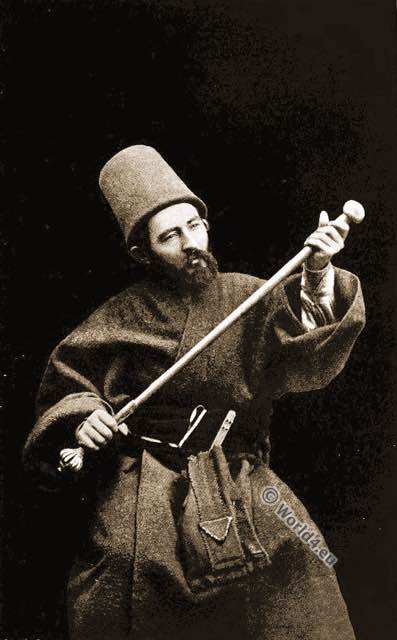

THE COSTUMES, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, AND SYMBOLIC OBJECTS OF THE DERVISHES.

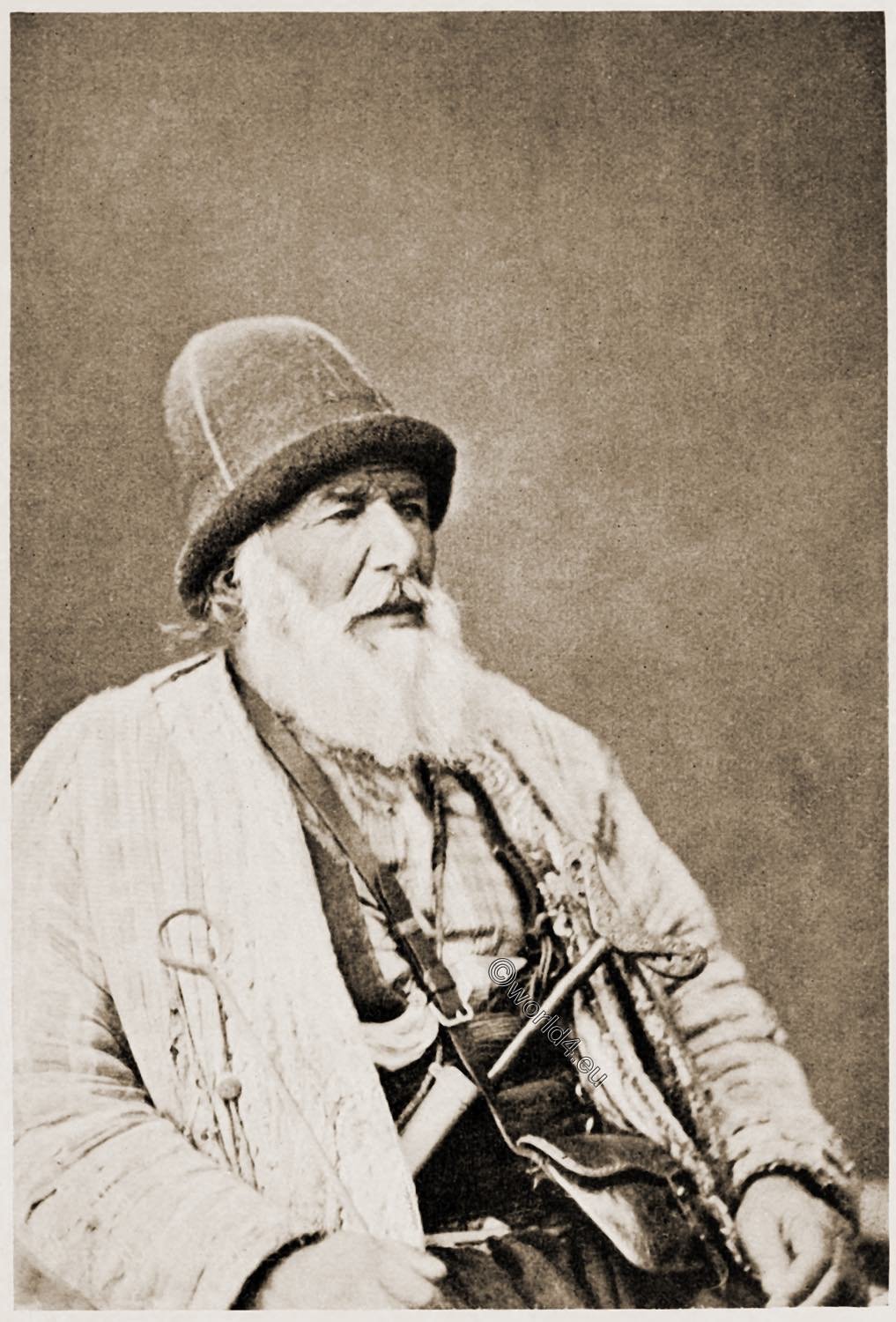

THE Dervishes of the various Orders may be easily distinguished from, their fellow-men, and also, generally, from each other, by their costumes, and, more particularly, by the shape of their headdresses; and to the latter, as well as to every other article of their clothing, some symbolic meaning, and, in many cases, some legend is attached.

The Mevlevi Order

The out-of-door costume of the Mevlevi Order is said to have been adopted by their talented founder Mevlāna (Our Lord) Jelālū-‘d-Dīn *), as a sign of mourning for his friend and spiritual master, Shemsū-‘d-Dīn (“Sun of the Faith”).

It consists of a tall hat called a kulak, of undyed camel’s hair felt, in shape like an inverted plantpot. Their Sheikhs, who all claim descent from the family of the Prophet, are, on this account, entitled to wear round their kulah a green turban.

The legend attached to this head-dress says that the soul of Mohammed had a previous existence in the Alemi Ervah, or Spirit World, where Allah placed it in a vase of light of that shape.

*) Ǧalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad bin Šaiḫ Bahā’ ad-Dīn Muḥammad bin Ḥusain-i Balḫī-yi Rūmī, called Rumi for short. Born on 30 September 1207 in Balch, today in Afghanistan, or Wachsch near Qurghonteppa, today in Tajikistan; died on 17 December 1273 in Konya, was a Persian Sufi mystic, scholar and one of the most important Persian-speaking poets of the Middle Ages. From his followers, especially the dervishes, he was nicknamed Maulana, “our master” (from Arabic Maulā). The Mevlevi Dervish Order is named after him.

Lay members

The lay members of the Order, who do not wear the Dervish dress except when taking part in its ceremonies, often, when in private, lay aside their ordinary fez, or turban, and don the kulak, in order to enjoy the happy influence it is believed to exert on the wearer.

When the son of Othman I (1258-1326, Soliman Pasha, asked the blessing of the Mevlevi Grand Master at Konya on the expedition he was undertaking against the Byzantine Greeks, that dignitary placed on his head a kulak, and prophesied that “victory should go with him.” The prince showed his reverence for the gift by having it covered with silver.

Ottoman state headdress

So high was the favor which this Order enjoyed under the early Sultans, that their kulak became the state headdress at the Ottoman Court. It was worn, ornamented with gold embroidery, by successive “Commanders of the Faithful,” and also, variously decorated, by civil and military dignitaries until the beginning of the present century, when “the Reforming Sultan,” Mahmoud II (20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839), relegated its use to the officers of the Janissary Corps.

The Khirkha

The khirkha of the Mevlevi Order is a long, loose, wide-sleeved robe of fawn-colored cloth for ordinary wear, and of black stuff when used to cover the costume in which they dance. Like the mantles of the Dervishes generally, it is more or less a copy of that believed to have been worn by the Prophet.

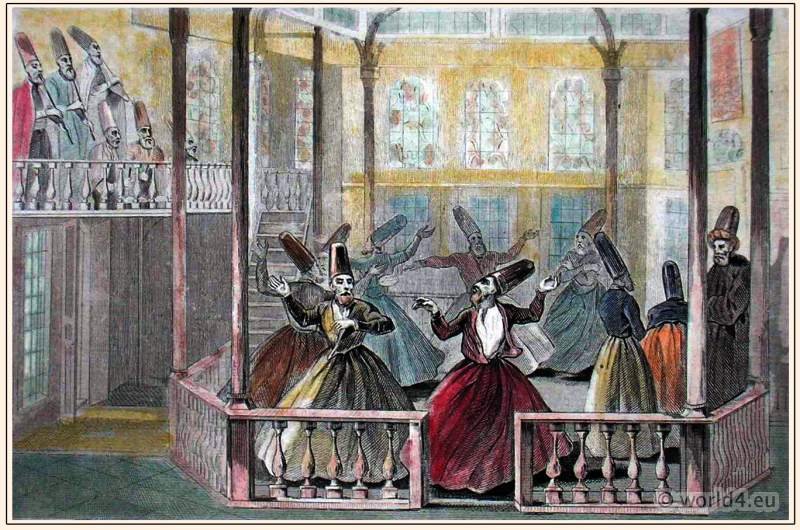

The Tennūri

The tennūri, or skirt, is worn only by Mevlevi Dervishes when performing their religious exercises. It may be red, yellow, or brown; is made very wide and without gores, and reaches to the feet. The rapid motion of the wearers when spinning round in their mystic dance extends these skirts to their full width, exposing to view the drawers of white linen worn beneath.

Stone of Contentment

The upper part of the body is clad in a short jacket of colored material with tight-fitting sleeves, and round the waist is bound the taybend, a girdle containing in its folds the “Stone of Contentment.”

This is commemorative of the stones formerly carried by begging Dervishes, who bound them close to their stomachs in order to suppress the pangs of hunger. Three were usually carried, though their wearers confidently believed that Allah would not fail to send relief before the necessity arose for using the full number.

Vocal and instrumental music

The use of vocal and instrumental music by this Order is said to have been adopted by its founder in order to rouse the lethargic natures of the inhabitants of Rūm to a devotional love of Allah through the allurement of sweet sounds addressed to their outward senses.

The orchestra of their chief Mevlana tekke at Konya is composed of six different instruments, among which are the reedflute and zither, the rebeck, a kind of violoncello, drums, and tambourines. In the generality of their Tekkehs, however, only zithers, reedflutes, and small hemispherical drums are used.

Flutes

The music of these flutes appears to have a singularly entrancing effect on the Dervishes whose exercises it accompanies. They are lulled and soothed by it to a forgetfulness of the visible world as if they indeed heard in its strains the mystic voices of the spiritual world.

The Divine Love

In the “Song of the Reed-flute” the Dervish poet symbolizes under the figure of a Lover sighing for his absent Mistress, the Soul of Man languishing for reunion with the Divine Love.

In the Mesnevi of Mevlana (Our Lord) Jelalu-‘D-Din, Muhammed, is given the following charmingly poetical account of the origin of the reed-flute’s mystic music which recalls the beautiful myth of Orpheus and his lute.

The Holy Mysteries

“One day the Prophet privately imparted to Ali the Secrets and Mysteries of the ‘Brethren of Sincerity’-evidently the original Brotherhood-with the injunction not to reveal them to anyone. For forty days Ali kept these secrets locked in his breast, but feeling no longer able to contain them, he fled into the desert.

Coming upon a well, he stooped as far as possible down its mouth, and to the earth and water divulged, one by one, these mysteries. Some days afterwards a shepherd youth, whose heart had been miraculously enlightened, perceived a single reed growing up out of the well. He cut it down, drilled holes in it, and, while pasturing his sheep in the neighborhood, breathed through the flute he had made melodies like those performed by the Dervish Lovers of Allah.

Soon the various Arab tribes heard of the youth’s wonderful flute-playing, and came to listen to it, accompanied by their sheep and camels, which forgot to graze while hearkening. The nomad shepherds wept for joy and delight, and broke forth into transports and ecstasies.

The fame of this music at length reached the Prophet, who sent for the youthful musician. When he began to play before them, all the holy disciples of Allah’s Messenger were moved to tears; they burst forth into shouts and exclamations of pure bliss, and lost all earthly consciousness. When he had ceased, the Prophet declared that the notes of the shepherd’s pipe were the interpretation of the Holy Mysteries which he had confided to the keeping of Ali.

“Thus it is,” adds the author, “that, until a man acquires the sincere devotion of the linnet-voiced reed flute, he cannot hear in its dulcet tones the Mysteries of the Brethren of Sincerity, nor realize the delights thereof; for faith is altogether a yearning of the heart and a gratification of the spiritual sense.

"The pangs my love for thee excites, can I to mortal breathe?

Ah no I Like Ali's, some pure fount my sighs, too, must receive.

Perchance some reeds may thence upspring its brink to overgrow,

And plaintive flutes those reeds become to murmur forth my woe."

The Three Principles of the Bektāshi Order

The cap, mantle, and girdle of the Bektāshi Order *) are called by their wearers “The Three Principles,” or “Points,” and have the following legendary origin. The Angel Gabriel on the occasion of one of his visits to the Prophet, cut his hair, shaved his beard, and then invested him with a cap, mantle, and girdle.

This act of service the Angel had previously performed only for Adam and Abraham. Mohammed then proceeded to do for Ali what Gabriel had done for him, and Ali in his turn performed this office for the Twelve Imāms.

*) The Bektāshi Tarīqa (short for Shī’ah Imāmī Alevī-Bektāshī Ṭarīqah) is one of the largest and most influential Islamic-Alevitian Dervish orders in Anatolia and the Balkans. The founder of the order is traditionally considered to be the Sufi and mystic Hadji Bektash, to whom all Alevis also refer.

The symbolic significance of the Bektāshi cap

Much symbolic significance is also attached to the Bektāshi cap. It is called a Taj, or “crown,” and is of white felt, shaped like a dome, and divided into four parts by grooves, called “Doors,” which allude to the four great stages of the spiritual life.

These “Doors” are subdivided by other three grooves into twelve parts, in remembrance of the twelve Imāms, and signify also the abandonment of twelve sins.

The turbans

The green or black turban worn round the cap is called the “parable” (Istīva). It signifies the abandonment of the world for the pursuit of high and holy things. As a general rule, the Sheikhs alone wear turbans. They, however, frequently appoint deputies who, as they bear the same honorary title, are also entitled to wear this distinctive head-dress.

Mystical significations of the cap

The cap has, besides, thirteen mystical significations attached to its several parts, among which are its border, circumference, “key,” or apex, and decoration.

This cap is, spiritually speaking, of two kinds: the “Crown of the Ignorant” (Tāj i Jahil), the wearers of which are often to be seen in the bazaars and public streets; and the “Crown of the Perfect” (Tāj i Kiamil), worn by those who shun, rather than seek, intercourse with the world.

The Alifer

There are also other forms of the Bektāshi Tāj, for, according to their saying: “As all the letters of the alphabet grew out of the first one, Alif, so the caps of the various Orders were derived from the Alifer, or original cap.” It is sometimes also called “the Founder” (Pir), and was in earlier times inscribed with the text: “All things will perish, save His face, and to Him will all things return.” On putting it on, the Dervish recites this invocation :-

“Sign of the glorious [name of the Pir of his Order]; of Kamber, [the groom of Ali]; of those who are dead; of the great family of the Imām Riza (The eighth Imam); permit me to put on this Crown, for I fully believe in its virtues. Great is Allah.”

The mantle of the Bektāshi Order

The mantle of the Bektāshi Order, though similar in shape, differs from that of the Mevlevi Dervishes in being decorated with twelve lines, or stripes, symbolical, like the grooves in their “Crowns,” of the Twelve Imāms, and is edged with green.

Among its mystical attributes are the following, with their meanings as given by the fourth Imām, Jafer-es-Sadik.

Its “True Faith” = to use it as a covering for the faults and follies of others.

Its Kibleh (point to which the attention is turned, or Mekka) = the Pir.

Its “Ablution” = the cleansing from sin.

Its “Obligation” = the forsaking of cupidity.

Its “Duty” = Contentment.

Its “Soul ” = the keeping of vows.

The different parts of this garment have also their several significations. Its border is symbolical of the condition of a Dervish; its collar, of submission; its exterior signifies” spiritual light,” and its interior “secrecy.”

The collar and edges are embroidered with Arabic words signifying “O Friend!” “O Healer!” “O Great One!” etc.

The vest of the Bektāshi Dervishes

The short tight-sleeved vest worn under the mantle is also decorated with twelve stripes of a colour different from the material, likewise symbolising the twelve Imāms.

The girdle of the Bektāshi Dervishes

The girdle worn folded round the waist under the mantle is made from the wool of the sheep sacrificed at the initiation of its owner, and is characterized by several symbolical names.

The Bektāshi Dervishes relate that its prototype was worn by Adam, and subsequently by a succession of sixteen Prophets, beginning with Seth, and including Elias, Jesus, and Mohammed. Their legend also says that the one presented to the Prophet by the Angel Gabriel bore the inscription: “There is no God but Allah, Mohammed is His Prophet, and Ali is His Friend.”

The rope of the Bektāshi Dervishes

The kamberieh is the rope placed round the neck of the Dervish at his initiation, and subsequently worn by him round his waist. Three knots are tied in it, called respectively the hand-tie, the tongue-tie, and the rein-tie, to remind the wearer of his vows of truth, honesty, and chastity.

The Palenk crystal, or stone

It is also commemorative of the cord with which Kamber, the groom of the Khalif Ali, was in the habit of tethering his master’s horse, “Dūldūl,” and serves to support a septagonal crystal, or stone, called the Palenk, symbolizing “the seven heavens and seven earths, seven seas and seven planets,” which, according to the Koran, obey Allah’s command and worship him by revolving round His holy seat.

Stone of Submission

Another stone, called the “Stone of Submission” (teshem tāsh) is worn suspended round the neck, and attached to it is the following curious legend:-

” Moses, the Servant of God, was in the habit of bathing in the Nile at a spot remote from that used by his fellows for that purpose, in order that they might not observe the radiance that emanated from his body.

The evil-minded took advantage of this custom of the Seer to circulate a report that he was leprous, or afflicted with elephantiasis, and for that reason was ashamed to wash with them. ‘But Allah cleared him from the scandal which they had spoken concerning him.’ *)

*) Koran, Chap. xxxiii.

One day when Moses was bathing, he laid his clothes on a stone by the riverside. The stone immediately set off at a rapid pace towards Misr (Cairo), followed by the Seer, who, eager in the chase after his garments, found himself amid the Israelites before he was aware.

When he came up with the stone, in his wrath he perforated it with his stick in twelve places. The stone then spake and said, ‘O Moses, I walked by the command of the Lord, and was the cause that thy purity has been witnessed by the people.’

Moses, being sorry for his unjust behavior, said, ‘I have perforated thee in twelve places, for which I ask thy forgiveness – A Dervish is forgiven by Dervishes.’ *) ‘Well, Moses,’ replied the stone, ‘I am satisfied with thy excuses; but now take a cord, and pass it through one of the holes, and keep me till thou requires a collar of penitence.’

*) This reputed saying of Moses has remained a current expression in the mouth of Dervishes.

Moses did as the stone commanded, and suspended it round his neck.” “And this,” says the Dervish Evliya, ” is the origin of the stones generally worn by Dervishes, and also of that put on by penitents, both of which are called sigil tashi.”

According to the same author, this is the stone that spoke to Moses at the rock of Horeb: “O Moses, put me on the ground, and give me twelve blows,” upon which twelve streams gushed out of the holes.

Another legend says that the “Stone of Submission” had its origin with Abū Bekr, who, having one day used language which gave offense to the Prophet, repented of his fault, and, to guard against its repetition, hung round his neck a pebble, which he placed in his mouth on entering the mosque.

When putting on for the first time the” Stone of Submission,” the Dervish utters this prayer :-

“O Allah, the rites of the Brethren have become my faith; no doubt now exists in my heart. As I hang round my neck the teshem tāsh, I give myself to Thee. In the name of Allah, the Merciful, and the Clement.” Then follows the recitation of the chapter of the Koran relative to the striking of the rock by Moses.

The Mengoosh Tāsh stone

A stone of a crescent shape called the mengoosh tāsh is also worn as an earring: It is supposed to represent the shoe of Ali’s horse “Dūldūl.” A Dervish who wears it in only one ear is called a Hassani; one who wears it in both, a Hussaini – these terms referring to the two sons of Ali.

The wearing of these earrings signifies that the Dervish accepts the words of his spiritual Guide as those of Allah, and that they are the laws that he hangs perpetually over his heart. When he inserts them, he prays: “End of all increase; Ring about the neck of all prosperity; Token of those who are in Paradise; Gift of the Martyr Shah (Hussein)! Cursed be Yezīd!” (his murderer).

The post or postaki

The post or postaki, the sheepskin mat on which the Dervish sits, has also its attributes. Its head signifies “Submission”; its feet, “Service”; the right side, the “Hand” given to a brother at his initiation; the left, “Honour”; the east, “Secrecy”; the west “Religion”; the middle, “Love.”

It has also, among other symbols, its Law, which means absorption into the Divine Love, when the soul is freed from the body, and wanders away to join other sympathetic spirits.

The chellek

A curved stick called the chellek is kept in the Bektāshi Tekkehs for the chastisement of erring Dervishes. It is commemorative of that used by the Khalif to chastise his groom, Kamber, who thenceforth humbly carried it in his girdle.

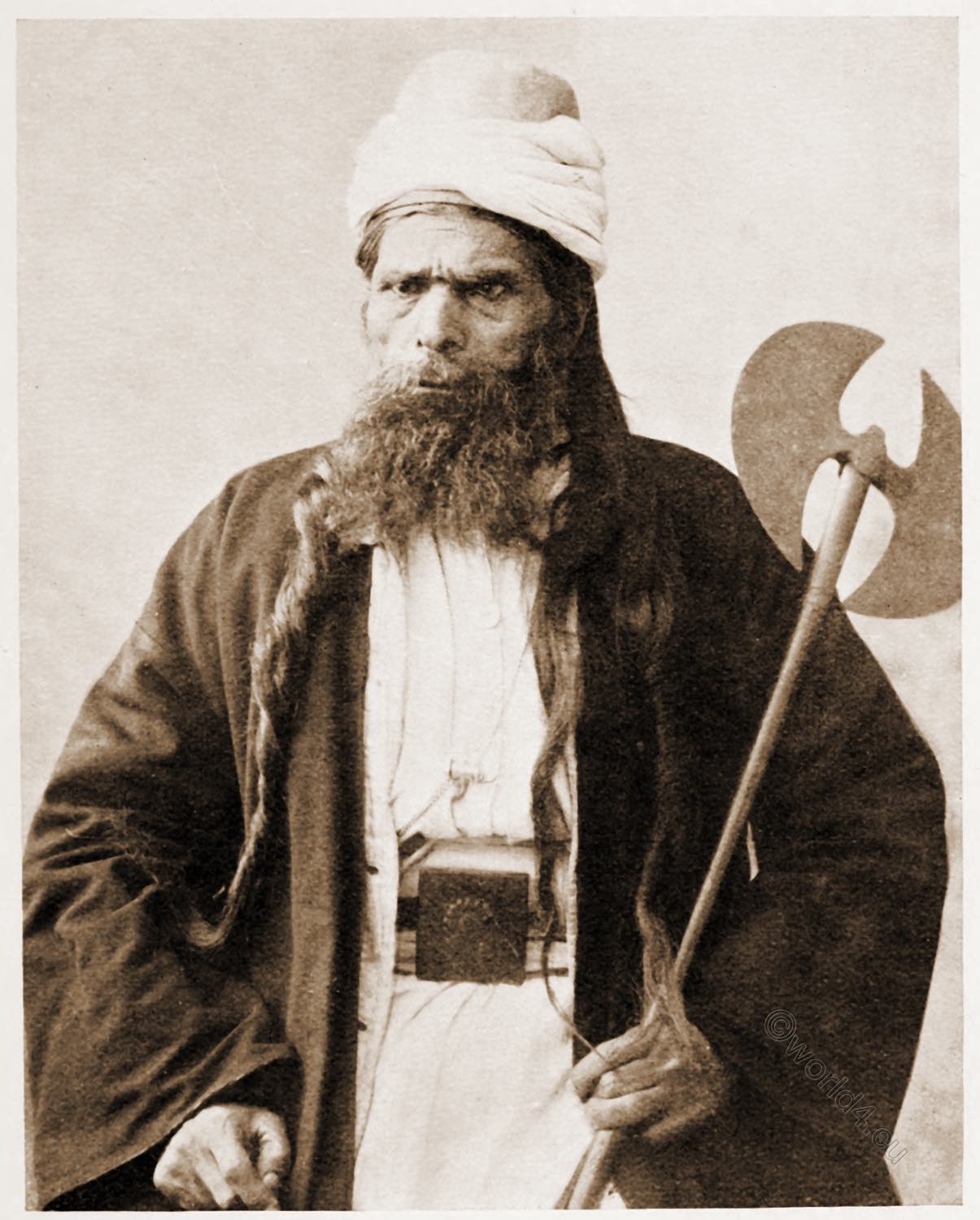

The tebber

A curiously shaped instrument called the tebber has been mentioned as used by the Bektāshis at their ceremonies of initiation, when it is carried by one of the “Interpreters,” or sponsors.

The members of this Order carry also a horn in shape like that of a wild goat, and a two-beaked alms-bowl. The former is sounded in the Tekkehs to call the Brethren to their meals and devotions, and is used generally as a signal from one Dervish to another.

It appears to be an imitation of that said to be carried by the Angel Gabriel, and is also called by one of the attributes of the Deity- “O Loving” – and a Bektāshi carrying it makes use of that exclamation.

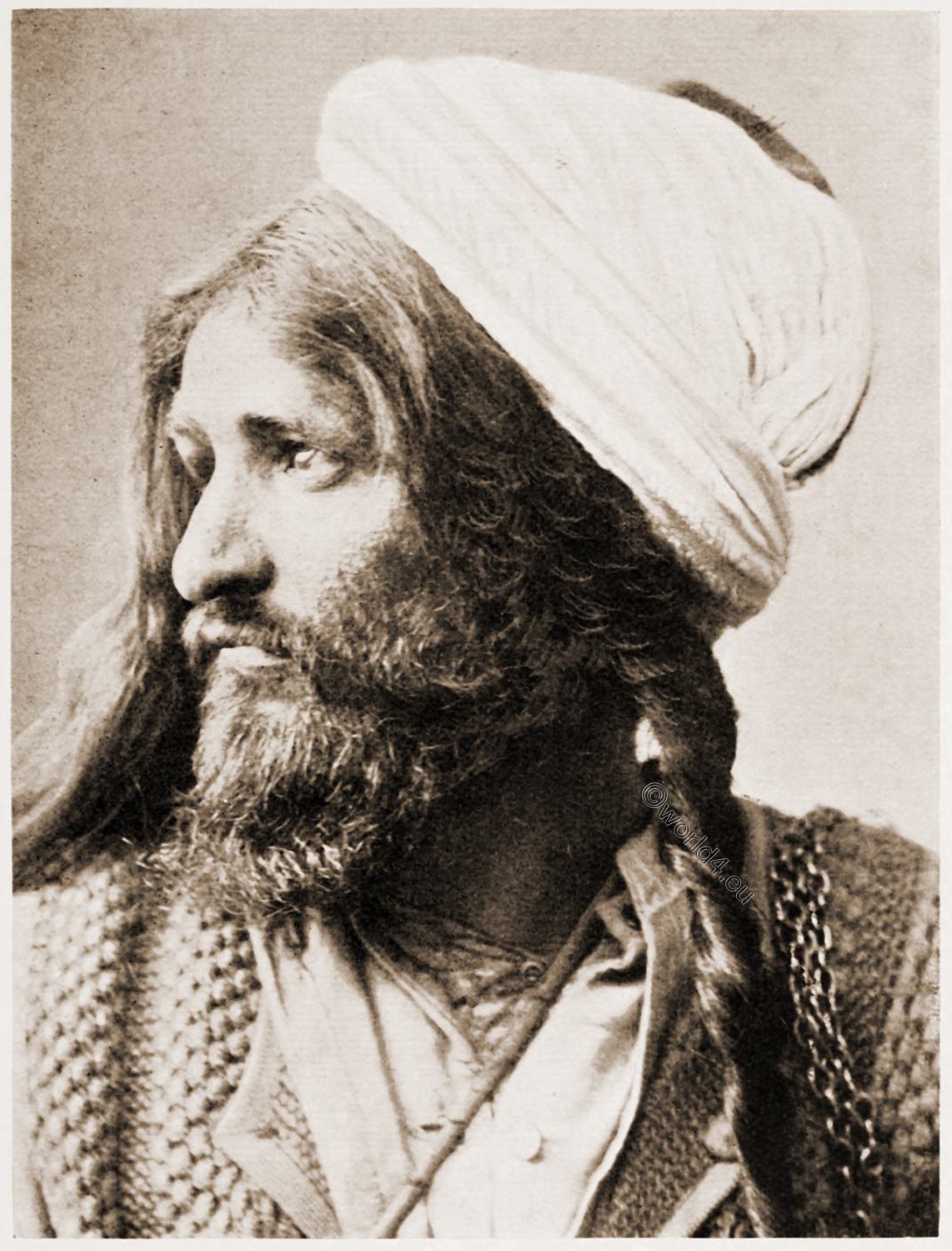

The Rifa’i or Rifāʿīya Sufi order (tariqa).

The Rifāʿīya or Rufaʽi is an Islamic Sufi order founded by the well-known Muslim mystic Ahmed Rifai. In the West the order is also known as “the Howling Dervishes” due to the ecstatic dhikr.

The cap of the Rifa’i, Howling Dervishes.

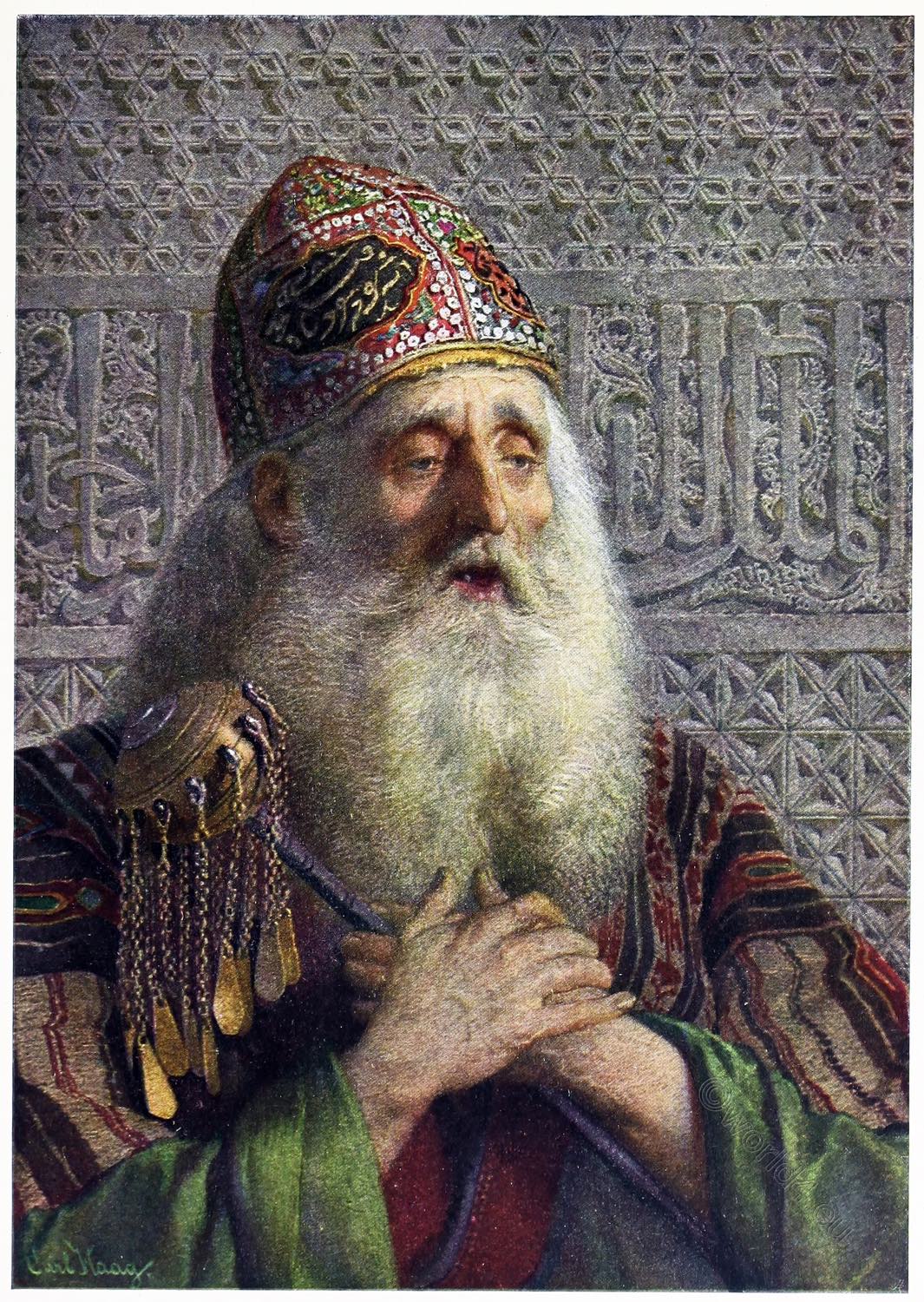

The cap of the Rifāʿīya, or, as they are commonly termed by Europeans, the “Howling” Dervishes, is very similar in form and material to that worn by the Bektāshi Order, and is also called a “Crown.”

It is of undyed felt, but divided into eight, instead of twelve grooves, each signifying the renunciation of a sin-or what they conceive to be such. The ” Crowns” of their Sheikhs are, however, divided into twelve grooves which have the same symbolism as those of the Bektāshis, and their turbans are black.

The mantles of the Rifa’i, Howling Dervishes

The mantles of the Rifāʿīya Order may be of any color, but are always bordered with green. The reason for this is given in the following somewhat vapid little legend; “The Prophet once, on receiving some good tidings from the Angel Gabriel, started up and turned round so suddenly that his green mantle fell off his shoulders.

His disciples (with his consent, presumably) took possession of the mantle, tore it into shreds, and sewed them round the edges of their own garments. As the Prophet frequently wore a black khirka, the Sheikhs of this Order often follow his example.” *)

*) Tradition relates that the Prophet, at his death, bequeathed his mantle to the Dervish Sheikh Uwais, referred to on p. 2. It is said to be a long robe of woollen material made with a collar, and wide sleeves reaching to the knee. The charge of this sacred garment has ever since remained in the family of Uwais. Some years ago when the hereditary guardian of this sacred relic happened to be a minor, a Vakīl, or deputy, was appointed by the Sultan to discharge this duty.

The mantle is enshrined in one of the buildings comprised within the Old Serai at Stamboul, where it is “venerated” by the Sultan and his Court on the occasion of the annual festival of the Khirka Shereef, and also on the occasion of important national events.

The “Roses” used by the Rifa’i, Howling Dervishes Order

The knives, red-hot irons and coals, and other instruments used by the Rifāʿīya Order in their extraordinary religious exercises, are called by the symbolic name of “Roses.” *) This is evidently connected with the rose-symbolism of the Kadiri Order, whose Pir or founder, Abdul Kādr Ghilāni, was, as above mentioned, the uncle and spiritual teacher of the Pir of the Rifāʿīya Dervishes.

*) To speak of wounds as “flowers” is a common figure of speech with Eastern poets. Compare, for instance, Gibb, Ottoman Poetry, p. 240.

The Kādiri Rose

The Kādiri Rose, embroidered on the “Crowns” of the Brethren of that Order, is to them full of mystic meaning. Tradition says that the Prophet bestowed the name of his “Two Roses” on his grandsons, Hasan and Hussain; and the Sheikhs of the Order, who all claim descent from the family of Mohammed, are credited with the possession of peculiar powers in connection with this flower. *)

*) Sulieman Effendi’s work on the Mevlad, or Birth of the Prophet, contains the following couplet in reference to Abdūl Kādr:-

Whenever he perspired, each drop became a rose,

Each drop, as down it rolled, was gathered as a

treasure.

According to a legend of this Order, its Pir was directed by Khidhr to proceed to Bagdad and there take up his abode. On arriving at that city Abdul Kādr received from the resident Sheikh a cup filled to the brim with water, which signified that the place was already full of holy men, and that there was consequently no room for him.

Replying in the same symbolic language, the Saint miraculously created a rose- it was mid-winter- and placed it in the cup, which did not even then overflow.

When this was carried back to the resident Sheikh, he and those with him read the message: “There is yet room in Bagdad for the Kādiri Rose.” Marvelling at the miracle, they exclaimed, “The Sheikh Abdul Kādr is our Rose!” and going out to meet their saintly guest, they conducted him into the city with every mark of respect.

Meaning of the Kādiri

The conventional rose of the Kādiri has eighteen petals arranged in three rings of five, six, and seven respectively, and its colors are yellow, red, white and black. The five petals are symbolical of the “five virtues” attributed by the Pir of the Order to the followers of Islam; the six are symbolical of the six characteristics of faith; and the seven refer to the seven verses of the Fatiha, the first chapter of the Koran (Surah Al-Fatihah), which is also denominated, among other honourable titles, the “Holy Crown,” and the “Mother of the Koran.”

The Hamzavi Order

The Hamzavi Order appear to have no distinctive costume, neither do they make use of any mystical symbols in their worship. On their tombstones, however, are sculptured peculiar signs consisting of single and double triangles, with dots above and below the angles, and the “Solomon’s Seal” of six points, without the dots.

The Rosary

The Dervish tesbeh, or Rosary, consists of ninety nine beads, the number of the “Beautiful names of Allah”; and as a Dervish invokes each one of these in his Zikr, he records it upon his beads.

The rosary is also divided into three equal parts, each of which signifies a formula of worship.

The foregoing are, so far as it is possible to ascertain, the chief among the emblematical meanings connected with the costumes worn and the objects used by the various Orders.

They, however, by no means exhaust the list. For, to quote again from Evliya Effendi, “a Dervish’s dress is covered without and within with a thousand and one symbols which give occasion for a thousand and one questions.

He who is capable of answering them all is a Master of the Science of Mysticism, a true Ascetic, and an Ocean of Knowledge.”

Source:

- Mysticism and magic in Turkey; an account of the religious doctrines, monastic organisation, and ecstatic powers of the dervish orders by Lucy Mary Jane Garnett. New York, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1912.

- The ‘old’ Water-colour society by Charles Holme (1848-1923). London; New York: Offices of ‘The Studio’. Royal Society of Painters in Water-Colours.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.