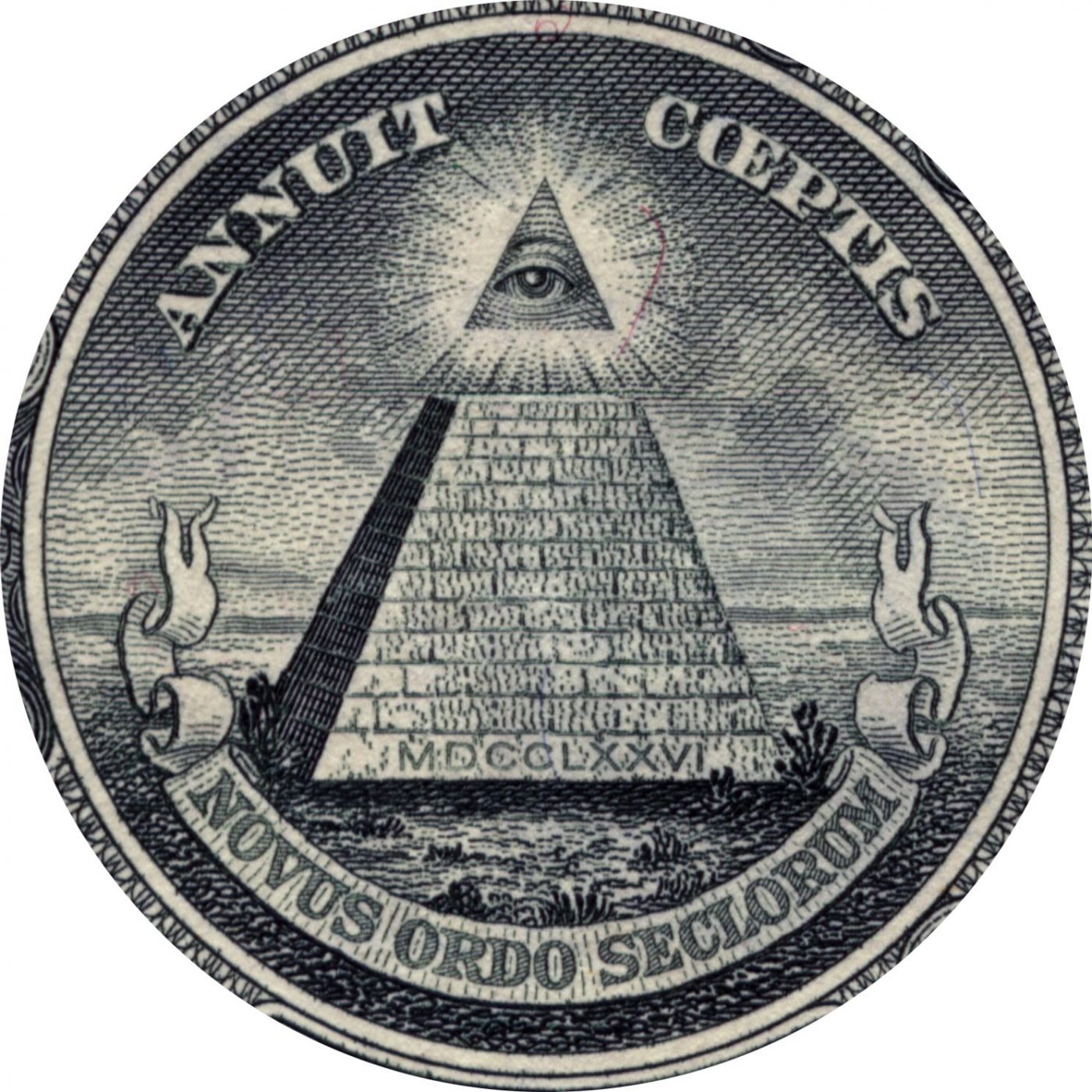

Eye of Providence which appears on the United States one-dollar bill is a symbol that is usually interpreted as the eye of God that sees everything, and is usually enclosed in a triangle that refers to the Trinity.

THE ILLUMINATI.

By the suppression of the Jesuit order by Clement XIV., the results of two centuries of painful toil in the interest of a universal ecclesiastical dominion were undone. Then it was that an ingenious mind conceived the thought of employing on behalf of enlightenment such instrumentality as the Jesuits had employed against it. lt was a pupil of the jesuits to whom this thought first occurred: their mechanical, soul-stifling method of education had made him their enemy; but besides he had learned the artifices and the secrets of the Jesuits, and hoped that by imitating them in a Catholic country likely to be influenced by such arts, he might thereby promote the very opposite interests.

Adam Weishaupt was born in 1748, and when only 25 years of age was professor of canon law and jurisprudence in the university of Ingolstadt, and also lecturer on history and philosophy, being the first in that institute to deliver lectures in the German language, and in consonance with the more enlightened spirit of the age. The intrigues of the ousted Fathers against their: successor in a professorial chair which they had held for nearly a century forced to maturity the thought which he had cherished from his student days: and the founding in the neighboring village of Burghausen of a lodge of Rosicrucians, who were trying to attract to themselves his students, decided him to carry his idea into execution.

On May 1, 1776, he founded the Order of Perfectibilists (The 18th Century Bavarian Order of the Illuminati) to which he afterward gave the name Illuminists (Illuminati). To propagate this institution and to strengthen it he adopted measures which, in the circumstances of the time, seemed not unpractical. First, he adopted entire the hierarchic system of government existing among the Jesuits=-despotic rule from top to bottom; secondly, he employed Freemasonry to promote the ends of his order, just as the Jesuits had attempted to do.

Accordingly Weishaupt, who was full of vanity, ambition, and desire of revenge, but knew nothing of the true Freemasonry, only of its perversions, obtained admission to the order in a lodge in Munich. Hence it is not true that the Freemasons founded the league of the Illuminati, but rather than an order that arose outside of the lodge simply made use of Freemasonry and so to the defeated reactionary movement against Freemasonry now succeeded an unmasonic revolutionary movement.

In executing his plan Weishaupt was assisted mainly by Francis Xavier von Zwackh (1756 – 1843), of Landshut, councilor to the government of the Bavarian Palatinate, a man initiated in the highest degrees of masonry. Several years after its foundation the order of the Illuminati was still confined to South Germany, or even to Bavaria; but as Weishaupt desired that the north also, and Protestants no less than Catholics, should take an interest in his institute, he sent the Marquis von Costanza (or Costanzo), Bavarian chamberlain, to Frankfurt am Main in 1779 to win over to the order the lodges in that city.

Costanzo himself had little success, the rich merchants of Frankfort being averse to anything that would unsettle the peace of the world; but a young man whose acquaintance he made was destined to be, after Weishaupt, the most effective promoter of the new society. This was Baron Adolf von Knigge, well known for his much-read book. “Ueber den Umgang mit Menschen.” He was born in 1752, and from his youth up had been an amateur of spiritism (ghostseership). He was already an Initiate of the higher degrees of the Strict Observance; but, dissatisfied with that order, he adopted the idea of Illuminism enthusiastically, and brought into the system a number of men who became its apostles; for example, Bode, the translator; Francis von Ditfurth (Franz Georg Wilhelm Ludwig von Ditfurth 1840 – 1909), associate justice, of Weimar. With these two Knigge attended the Conventus of Wilhelmsbad, and there championed the cause of Illuminism stoutly, and helped to give the, deathblow to Templarism.

And now as Knigge, who supposed the order to- be an ancient one, entered into a correspondence with Weishaupt, he was not a little astonished on learning from him that the society was as yet no more than an embryo: in fact, it had only the degree of the minor Illuminates (Kleine Illuminaten). Nothing disheartened, however, he journeyed to Bavaria, and was admitted to the order in splendid style. But his lively fancy led him to develop the order further; and the sober-mindel Weishaupt, whose gifts were those of the thinker rather than of the contriver of forms, left to Knigge the elaboration of the several degrees and their Lessons, in which both were agreed that allusions to the fireworship and lightworship of the Persians should be employed, as typical of the spiritual fire and spiritual light of Illuminism.

The groundwork of the polity of the Illuminati was as follows: A supreme president ruled the whole, having next below him two officers, each of whom again had two others under him, and so on, so that the first could most conveniently govern all. The doings of the order were kept most strictly secret. Each member took the name of some historic or mythic personage of distinction: Weishaupt was Spartacus; Zwackh, Cato; Costanzo, Diomede; Knigge, Philo; Ditfurth, Minos; Nicolai, Lucian, and so on. Countries and cities also had pseudonyms: Munich was Athens; Frankfort, Edessa; Austria, Egypt; Franconia, Illyria, and so forth. In correspondence the members used a secret cipher, numbers taking the place of letters; in reckoning time they followed the calendar of the ancient Persians with the Persian names of months and the Persian aera.

The number of degrees and their designations were never definitely fixed, hence they are different in different localities. But all the accounts agree that there were three principal degrees. The first of these, the School of Plants (german: Pflanzschule) was designed to receive youths approaching adult age. The candidate for admission was at first a Novice, and, except the one who indoctrinated him, knew no member of the order. He was required, by submitting a detailed account of his life, with full particulars as to all his doings, and by keeping a journal, to prove himself a fit subject for admission, and one likely to be of service to the order.

From the grade of Novice he passed to that of Minerval. The members of the Minerval class formed a sort of learned society, which occupied itself with answering questions in the domain of morals. The Minervals, furthermore, were required to make known what they thought of the order, and what they expected of it, and they assumed the obligation of obedience. They were under the eye of their superior officers, read and wrote whatever superiors required of them, and spied on each other, and reported one another’s faults to superiors as in the Jesuit system.

The leaders of the Minervals were called Minor Illuminati; were taken by surprise at the meetings of their degree and nominated to that dignity – a method that wonderfully stimulated ambition; they were instructed in the management and oversight of their subjects, and practiced themselves in that art; they were besides required to report their experiences. The second principal degree was Freemasonry, through the three original degrees of which and the two so-called Scottish degrees the Illuminati passed; and strenuous effort was made to have the masonic lodges adopt a system agreeable to the ideas of the Illuminati, so that the membership of the order might be steadily increased.

The three original degrees of masonry were imparted to the regular Illuminati without ceremonies. The members of the two Scottish degrees were called Greater Illuminati, and the task of these was to study the characters of their fellowmembers; and Dirigent Illuminati, who presided over the several divisions of the illuministic masonry.

The third and highest degree was that of the Mysteries, comprising the four stages of Priest, Regent, Magus and King (rex). This principal degree was elaborated only in part, and was not brought into use. In these four divisions of the third degree the ends of the order were, according to Knigge’s plan, to be explained. The supreme heads of the several divisions of the order were called Areopagites, but their functions were never fully defined. It was proposed also to add a department for women. The aims of this organization of the Illuminati remind us forcibly of those of the Pythagorean League. They contemplated, not a sudden and violent but a gradual and peaceful revolution, in which the Illuminism of the 18th century should gain the victory. This revolution was to be effected by winning for the order all the considerable intellectual forces of the time, though the new associates were only little by little to learn what the aims of the order were.

And inasmuch as, the members, when they should have among their number all those forces, must everywhere attain the highest places in government, the triumph of their enlightened principles could not be for long delayed. In the superior degrees the members were to be taught as a grand secret of the order that the means whereby the redemption of mankind was one day to be accomplished was Secret Schools of Wisdom. These would lift man out of his fallen estate: these would, without violence, sweep Princes and National boundaries from the face of the earth, and constitute the human race one family, every housefather a priest and lord of his own, and Reason the one law code of mankind. To imbue the minds of men with these principles, illuminist books were prescribed to the members for their reading. In sharp contrast to the masonic systems in which Jesuits had had a hand, the Illuminati avoided all forms which might suggest obedience to any religion or church, and welcomed whatever favored the dominance of reason and the overthrow of revelation.

In the very short period of its existence the order of the Illuminati attained a membership of 2,000 a result very materially promoted by the’ rule that any member possessing authority from the superiors could! admit a candidate. Among the members were many men eminent, both socially and in science, as the dukes of Saxe-Gotha (Ernest), Brunswick (Ferdinand), of Saxe-Weimar (Charles Augustus, while yet only heir of the ducal crown); Dalberg, who was afterward prince-bishop; Montgilas, afterward minister of state; President Count Geinsheim; the celebrated philosopher Baader; Professor Semmer of Ingolstadt, Moldenhauer of Kiel, Feder of Goettingen; the educator Leuchsenring of Darmstadt (Franz Michael Leuchsenring 1746 – 1827); the Catholic cathedral prebendaries Schroeckenstein of Eichstadt and Schmelzer of Mayence (Mainz); Haefelin, bishop of Munich; the authors Bahrdt, Biester, Gedike, Bode, Nicolai, etc. Goethe, Herder, and probably Pestalozzi also belonged to the order. The league in “Wilhelm Meister” (a late novel by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe publ. 1795/96) reminds us strongly of the Illuminati.

The order was not yet spread abroad beyond the German borders, though a few Frenchmen had been admitted while visiting Germany; but its plans. were already reaching out farther. And now the head of the whole organization was to be the General (as among the Jesuits); under him there was to be in each country a head officer, the National; in each principal division of a country a Provincial; in subdivisions of provinces a Prefect, and so on.

This aping of Jesuit polity and the imprudent admission of objectionable or indifferent characters proved the ruin of the order. Despotic rule and espionage could never promote the cause of liberty and enlightenment and the founder of the order proposed to make enlightenment the means of attaining liberty.

Then the dissensions ever growing more serious between Weishaupt and Knigge. Whereas Weishaupt cared only for the ends of the society, all else being in his eyes only incidental, mere formalism, Knigge, on the other hand, being a man of the world, shrank in horror from the program of his associate: religion, morality, the State were imperiled. He dreaded Liberalist books, and would have been far better pleased to see the order working on the lines of the Freemasons of that day, though with an elaborate ceremonial and manifold degrees and mysteries, and with some harmless, innocent ideal of human welfare and brotherly love as the object of their endeavors. Weishaupt called Knigge’s pet contrivance tinsel and trumpery and child’s playthings, and the pair of “Areopagites” grew steadily ever more asunder.

This rising storm within boded less ill to the order than the attacks from without growing from day to day more violent. Illuminism was assailed by enemies of all sorts, that sprung up like mushrooms. First there were the masonic systems of the reactionary or superstitious kind, such as the Rosicrucians, the Asiatic Brethren, the African Masterbuilders, the Swedish Rite, the remnant of the Strict Observance, etc.; then such of the Illuminati as thought the hopes of the order had been disappointed, or who expected to profit by a betrayal of the order to the enemies of liberty and light; finally, and above all, there were the sons of Loyola, ever laboring industriously in the dark though their society had been suppressed, and now again, thanks to the licentious, bigoted despotic Elector Charles Theodore, possessing great influence in Bavaria, the country in which the membership of the Order of Illuminati was of longest standing and most numerous.

At that court, the seat of corruption, some courtiers, professors, and clergymen who had been members of the order, with the secret pamphleteer, Joseph Utzschneider (1763-1840), at their head, played traitor, charging the order with rebellion, infidelity, and all manner of vices and crimes, and at the same time, without ado, classing with the Illuminati the Freemasons.

By a decree of August 2, 1784, the lodges of all secret societies established without government’s approval, including the Illuminati and the Freemasons, were banned. The masonic lodges submitted at once, and closed their doors; but Weishaupt and his associates went on with their work, hoping to change the mind of the Elector by bringing up for public discussion their rules and their usages. Vain hope.

The Elector’s confessor, Father Frank, an ex-Jesuit, who already had labored against Freemasonry, procured on March 2, 1781, a second decree: by which the previous one was con finned, and all secret organizations that continued to exist in violation of it, and specifically the Order of Illuminati, were forbidden to hold meetings, and all their property was confiscated.

The Minister of State, Aloysius Freiherr von Kreitmayr (1705) – 1790), distinguished himself by the rigor with which he executed the ukaz. Weishaupt was deposed from his place at Ingolstadt, expelled from that city, and declared incapable of legal defense; he had to flee the country. He first tarried in Ratisbon; but soon, in consequence of the discovery of compromising documents in a search of the houses of Illuminati, very grave charges were brought against the members, and the Elector became alarmed for his throne. Without distinction of class or station a prosecution was entered against all persons accused of membership in the order, or even suspected of sympathy with it, and they were imprisoned, deposed from office, banished, and in the case of persons of the lower classes, punished with stripes.

This whole business was managed, without any recourse to’ the regular tribunals, by a special commission under Court direction. This persecution lasted till after the outbreak of the French Revolution, and a refusal to condemn the French people was taken as evidence of a revolutionary spirit. This system naturally fostered ignorance among the lower classes, but among educated people it tended to spread the principles of Illuminism, and to awaken opposition to monkish rule in the state.

Weishaupt, no longer safe at Ratisbon, the Bavarian government having set a price on his head, fled to Gotha, where Duke Ernest, a member of the order, protected him, and made him Court councilor. Here he lived till 1830, but he failed to resuscitate his order on an improved plan.

As for Knigge, he made haste to quit the incriminated order, and in his prim, emasculate “Umgang mit Menschen,” (interpersonal skills) strongly condemned all “secret societies” – he, the old-time Templar, Freemason, and Illuminist. Few were so stout-hearted and firm as Ignatius von Born (1742 – 1791), the naturalist, a native of Transylvania, who had been a Jesuit, but who, after the suppression of the Society of Jesus, had joined the Illuminati and become a Freemason.

After the suppression of the Bavarian lodges, Born, who was then in the service of the Emperor Joseph II. at Vienna, sent back to the Bavarian Academy of Sciences his diploma as member of that” body, accompanying it with a letter in which he bluntly declared that he would rather be a Freemason than a member of a body with which he had nothing in common. And thus was the cry of Voltaire, “Ecrasons l’Infame,” taken up by the party against which it was first uttered, and by them given effect in the shape of a most infamous persecution, before men of enlightenment had made the first move toward “stamping out” what to them seemed an “infamy.” For the rest it is said that the suppression of the Illuminati was the result of an understanding with Frederic the Great, whose policy was threatened by the order.

IMITATIONS OF ILLUMINISM.

Not long after the break-up of the Order of Illuminati in the South, a similar order sprang up in Northern Germany. It originated in the brain of a man unfortunately at once a zealous Illuminist and a morally depraved vagabond, who made a deplorable misuse of the talents with which nature had endowed him richly. This was Dr. Charles Frederic Bahrdt (Karl Friedrich Bahrdt 1741 – 1792), Protestant theologian, sometime preacher, professor, or teacher in sundry places, and once even keeper of an eating house at Halle. In 1788 it occurred to him to found an association to promote enlightened views, and his plan was to combine it with the masonic society, of which he had become a member in England. The projected association he called the “German Union of the Twenty-Two.” (Deutsche Union der XXI!.), for the reason, as he explained in a circular letter, that twenty-two men had formed a union for the ends set forth.

The Union was to be organized on the plan of Jesus Christ, whom Bahrdt in a voluminous work portrayed as the founder of a sort of Freemasonry, and of whose miracles he offered a rather forced natural explanation. In accordance with this plan the association was to be a “silent brotherhood” that was to hurl from their throne superstition and fanaticism, and this chiefly by the literary activity of the members. The literary labor was ingeniously organized in such fashion that the Union would by diligent effort in time gain control of the press and the whole book trade, thus acquiring the means of insuring the triumph of enlightenment.

Outwardly the Union was to have the appearance of a purely literary association: but inwardly it was to consist of three degrees, of which the lower ones were to be simply reading societies, while the third alone would understand the real purpose of the order, viz., advancement of science, art, commerce, and religion, betterment of education, encouragement of men of talent, remuneration for services, provision for meritorious workers in age and misfortune, also for the widows and orphans of members.

But inasmuch as Bahrdt had painted this beautiful picture solely to make money, the Deutsche Union existed only on paper; but it wrought for its projector a protracted term of imprisonment, which he survived but a short time; he died in 1792.

Another imitation of the Order of Illuminati, the League of the Evergetes (Bund der Evergeten, or benefactors, or welldoers) which sprang up at the close of the 18th century, had a longer term of life, though but little expansion. Its activity extended over all the arts and sciences, except positive theology and positive jurisprudence. The members were designated after the manner of the Illuminati; but they acknowledged no unknown superiors.

Time was reckoned from the death of Socrates, B. C. 400. The supreme head was called Archiepistat (archiepistates, chief overseer); there were two degrees, of which only the higher one had a political aim, popular representation. Fessler, by his protests against such tendencies, Drought about a split in the association, and afterward his adversaries tried to convert it into a sort of moral Femegericht *) by tracking and branding all offenses. One of the three leaders betrayed the other two, and was with them put in prison, but soon afterward released; that ended the association.

*) Secret, legally illegitimate meeting to pass judgement on certain political murders, attacks and the like. The term feme (also veme from Middle Low German veime = punishment) was originally used for the jurisdiction of feme courts, a special form of medieval criminal justice, and the punishments imposed by them.

FREEMASONRY AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

That there was any alliance of the Freemasons, or even of the Illuminists, with the men of the French Revolution, which broke out in 1789, can be affirmed only by those who are ignorant of history or wilfully blind-by men like the Privy Councilor Grolman of Giessen, friend of Stark (significantly named in the Strict Observance, Knight of the Golden Crab), or, like the abbe and canon Augustin Barruel in France, or the ship’s captain and professor, John Robinson, in England: their allegations were received only with ridicule, and passed into oblivion. As we have seen, the Illuminati were to be found only in Germany, where no revolution took place: in fact, they were no longer in existence when the French revolution broke out.

As for the Freemasons, we have already shown that they were opposed to the movement; but that movement could have no other ground than the dissatisfaction of the people of France with the shameful Bourbon dynasty, whose mischief could not be repaired by the well-intentioned but narrow-minded Louis XVI. No critical or serious work of history gives any justification of the belief that Freemasonry had a hand in bringing about that Revolution: but a decisive proof of the true relation of Freemasonry to the troubles of those times is had in the fact that the Terror made an end of the Grand Orient of France. All the clubs of the French Revolution were open: the people would not tolerate secret clubs, not even private assemblages, and hence as early as 1791 began to persecute the Freemasons as aristocrats.

The Grandmaster then existing, Louis Philip Joseph, Duke of Orleans, gave up his title, as we know, and called himself Citizen Equality, and at last, in 1793, declared that he had given up the “phantom” of equality, found in Masonry, for the reality; that in the Republic there should be no Mysteries: and, therefore, he would no more have anything to do with Freemasonry. That same year his head fell under the guillotine, and his blood sealed the “reality of equality”; and most of the members of the two zealous lodges, those of the “Contrat Social” and of the “Noeuf Soeurs” were taught, when they met with a like fate, that “real” equality was a more dreadful “phantom” than those they had pursued in the lodges. Only three lodges continued in- existence through the Terror by extreme caution and secrecy, and not till the fall of the Terrorists did Brother Roettiers de Montaleau (1748 – 1808) come forth from the prison in which he had been incarcerated simply because he was a Freemason.

Thus did French Masonry weather the terrible storm of the Revolution; the German lodges in the mean time were busy in reforming and strengthening themselves; for a season they withdrew into retirement, and exerted no longer any influence on public affairs. Superstition and child’s play fell into disrepute: the Rosicrucians, the “Asian” and “African” orders, the Templars, and their like, condemned by public opinion, had to give up their absurdities and return to right reason.

The general league of German Freemasons projected in 1790 by Bode of Gotha, failed of realization in consequence of the death soon afterward of that enlightened mason (1793); but its purpose was served, though not in its whole extent, by the sturdy Eclectic League of Masonry (Ekletische Freimaurerbund) founded as early as 1783, with headquarters at Frankfort. This League has ever since rendered notable service to the cause of genuine Freemasonry.

Source: Mysteria: History of the secret doctrines and mystic rites of ancient religions and medieval and modern secret orders by Otto Henne am Rhyn, Joseph Fitzgerald. New York: J. Fitzgerald 1895.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.