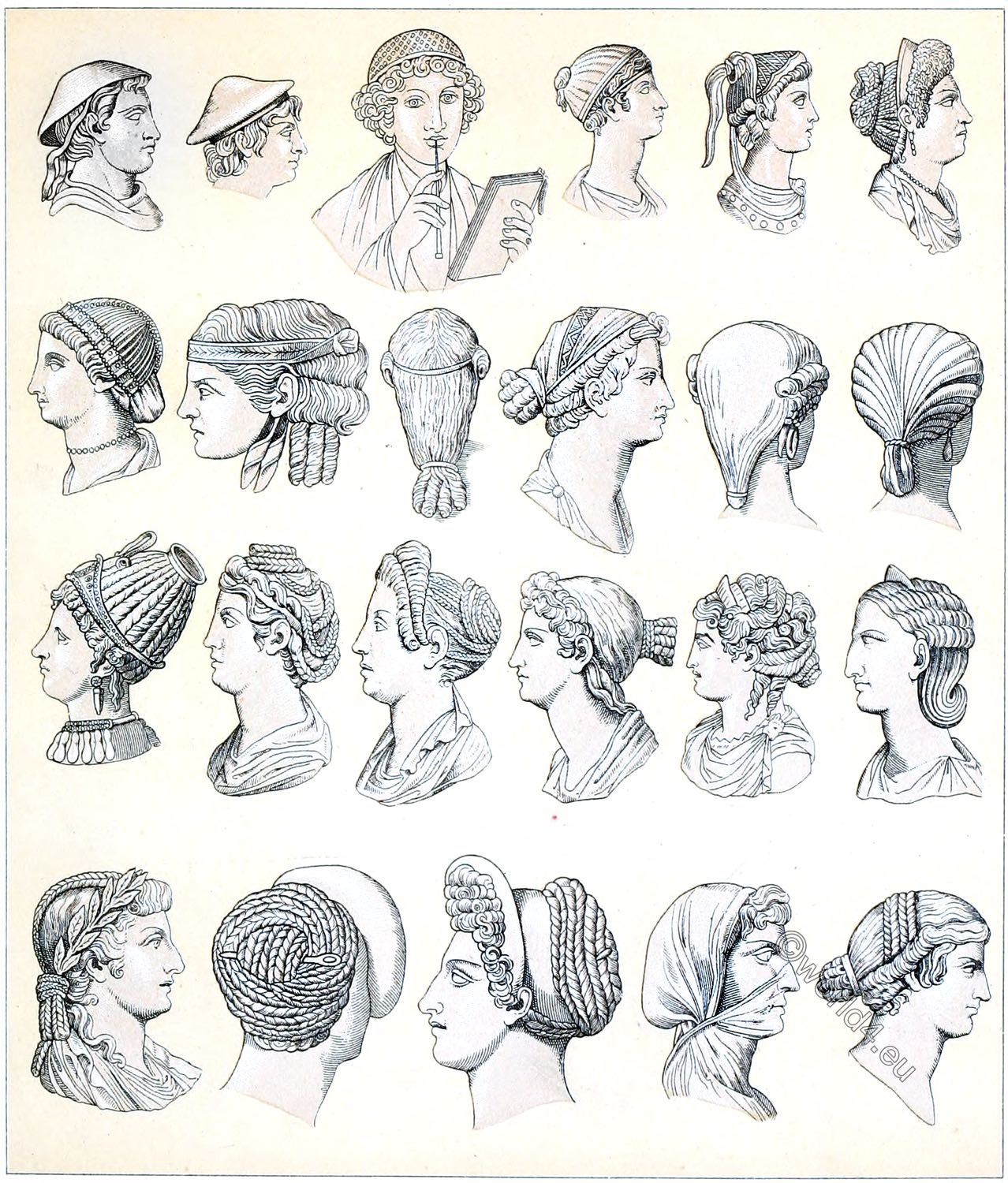

Ancient Greece Coiffures.

The Feminine Costume of the World. Coiffures. Part VIII. Ancient Greece. Plate 7.

Coiffures

The Beautiful Lines of the Greek Costumes.

1. Plain draped stuff with darker border, tied on back-hair, hanging and hiding neck.

2. Bacchante’s coiffure with small tresses tied up on top of head. Golden-yellow circle or bandlet on hairholds ivy-leaves descending on each side .

3. From statuette. Coiffure of Greek girl wearing mitra.

4. From statuette. Coiffure figuring a cushion partly of plain ribbon and beaded stuff. Worn high over the forehead.

5. Phrygian cap of Greek prisoners with strings passing under chin. Also worn by women.

6. Short drapery of plain material, fixed behind, adorned with laurel on the sides.

7. Hat wholly covering head. Large brim tucked up in front; free sides descending towards shoulders.

8. Small coiffure with narrow scrolled brim and two ribbons hanging together on each shoulder.

9. Woman’s coiffure with ball-crown and tucked brim embroidered and edged. Colored embroidery-stitches.

10. Diadem of goddess Artemis with engraved designs.

11. Large untrimmed hat.

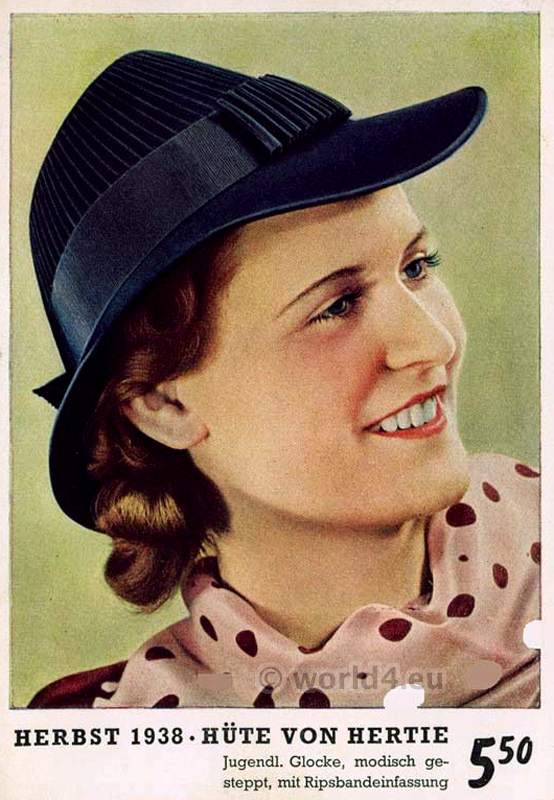

Hats and Head-dresses.

Greek women died their hair, which fact is revealed to us by Lucian (Dialogue of the Courtisans) when he puts these words in the mouth of the Courtisan Tryphoene: “Consider her well and look at her temples where some hair is still left, for all the rest of her head is covered with a wig; and when the color she takes care to dye it with has faded away, you will see it covered with grey hair. ” The word used to indicate this false hair, was” penike “. It meant a wig, or false curls.

Elien says, speaking of Atalanta’s hair: “Her hair was fair, and got its color from nature, not from art or from the drugs women use to give their hair its color.”

Ovid thus speaks of women in his “Art of Loving”: “Let each one choose what befits her best, and consult her mirror. A somewhat long face requires a head-dress to be parted in the middle and not rising on the head. Such was Laodomina with her lovely hair. Round faces require a small bow on the top of the forehead so as to let the ears appear. Another should let her hair fall on her shoulders, as you wear it, O Apollo, when you take up your melodious lyre. And let another yet tie her hair behind after the fashion of Diana.”

Horace says: “Having carelessly bound her hair in the fashion of Lacedaemonian women … “It becomes this one to wear her hair puffed out, and that one to lay it flat. One finds it befitting to set it in the shape of a tortoise, like the one Mercury once made a lyre out of; and another if she would appear her best must leave it in small ripples about her head. Only a poet imbibed with art could give members of the fair sex such advice worthy of the taste of an artist.

Both sexes had customs for hair-dressing that were peculiar to them; as, hair cut short for men, and, for women, the luxurious tresses that so advantageously adorned the beauty of virgins, or set off their charms in rising tiers of waves.

ORNAMENTS

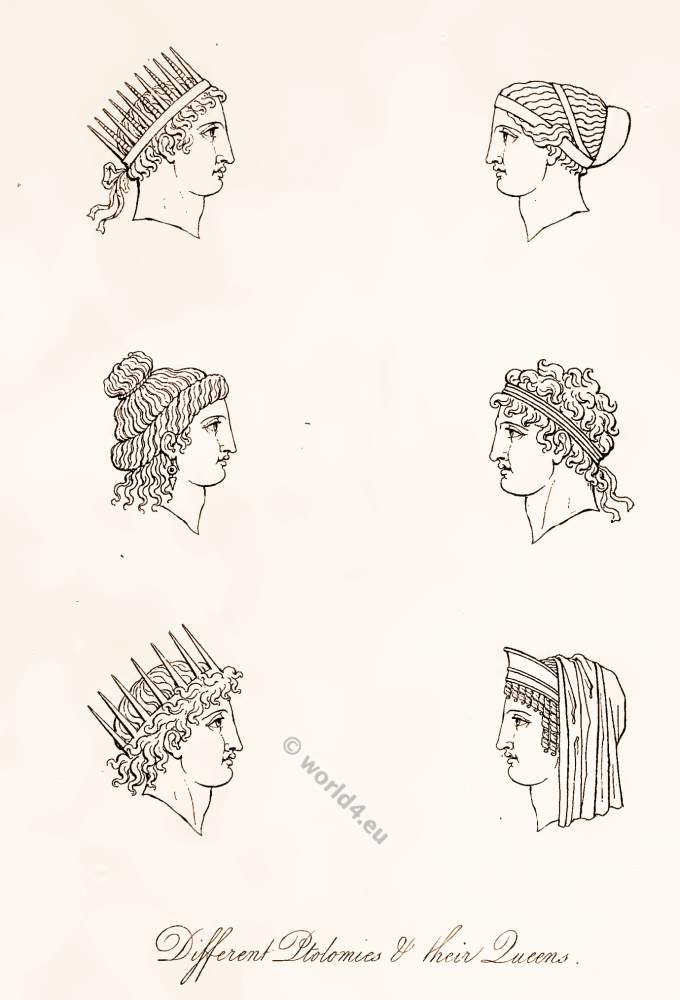

The head-ornaments for women were: the miter (mitre), the ampyx, the cecryphale, the tiara, the diadem, the anadème, the strophos, the kredemnon, the cheiromactres, the tholia and the calyptra.(1)

The mitre was of wool; the opisthosphendone was the part of it wrapping the back-hair; it was sling-shaped.

The ancients mention an ornament worn by women called the sphendone, from its resembling a sling. It was broad in the middle and was worn over the forehead, being tied behind by the thin ends.

(1) Nicolas Xavier Willemin’s Choix de Costumes civils et militaires des peuples de l’antiquité. Costumes des peuples de l’Europe. Troisième partie. Les Grecs. Coiffures et ornements de tête des femmes (1798-1802).

Other writers mention the mitre. Virgil says: “The Syrian woman whose head was adorned with a small Greek mitre … “The amphyx and the cecryphale were likewise nets. The former was circular and in the shape of a cap; the latter sling shaped, like the mitre.

Theocrites writes of it: “A woman of enchanting beauty, clad in a peplos with her hair in a net.”

The diadem, anadem and strophos were bands fastened on the head in diverse ways.

The diadem was a head ornament. It was of gold texture and garnished with gems. Its two ends were brought together and fastened behind.

The strophes was a band of wool worn around the head. Catullus says. in the “Nuptials of Thetis and Peleus” “Snow-white hands bound their rose-scented hair.”

Sappho speaks of the cheiromactres, in her songs when addressing Venus: “Despise not the cheiromactres or the purple veils of my dolls. I have sent them unto thee as precious gifts from thy dear Sappho.”

Homer also attributes as veils to Juno and Penelope the broad band “Kredemnon.”

By the cheiromactres of her dolls, Sappho means such a head ornament as described by Hecatus, the man who wrote of his travels in Asia.

The tholia and the calyptra were coifs of different shapes. The tholia was a cap narrowing to a point.

The cecryphal; From the Greek κεκρύφαλος, kekryphalos, is a type of female hairstyle from ancient Greece, forming a net or a strip of fabric holding the hair on the upper back of the skull.

The ampyx: A woman’s headband (sometimes of metal), for binding the front hair in Ancient Greece.

BRAIDS

It is on the braiding of their hair that women bestow most time and exhaust the secrets of their arts. Some use drugs to make it as brilliant as the noonday sun, they dye it like wool; or anon, discontent with the color given it by nature, they seek to give it a dazzling blond hue. Those that fancy that black hair suits’ them better waste their husband’s wealth on scents. “Their heads must exhale all the perfumes of Arabia. With iron instruments heated at a flame, they scroll the hair and twist into long rings. With what care they judge the placing of them so that they might fall exactly over their eyebrows! Scarcely may a narrow interval of forehead be seen. The back-hair proudly waves on the shoulders and down their back.” (Lucian: Treatise on Love.)

COLOR OF THE HAIR.

The handsomest of the forefathers of the Greeks and the greatest heroes were all pictured as having blond hair. Black hair and eyes still had, however, their own supporters. The question yet remains to be settled as to which deserves preference.

Jealous husbands would cut off their unfaithful wives’ hair, either as a punishment for their flirting, or in order by thus disfiguring them to make them stay at home.

CORYMBES

Girls contented themselves with simply coiling up their hair and Fastening it at the back of their head. This sort of head-dress was often called “corymb”. Sometimes they braided their hair so as to form a knot.

Women did not make so much fuss about their hair. They commonly went about bare-headed and tied their hair rather low behind, loose upon the head so that it fell in thick tufts under the ribbon fastening it. They sometimes covered their heads with the flap in their dress. Some had a kind of veil or a small piece of transparent stuff which they used especially for this purpose. The maidens wore them sometimes also.

KROBYLOS

Youths and maidens only combed their hair up around their head and tied it on the top without displaying the ribbon. This kind of head-dress wos called Krobylos.

Greek women had a talent for finding endless and various modes of dressing their hair.

All the virgins had their hair coiled up on the top of their head. The virgin-goddesses, Victory and Diana, are thus pictured.

Many of our head-dresses are taken from a Greek monochrome painting bearing the inscription, in Greek characters: “Alexander, the Athenian, made me.” This Alexander the Athenian was the author of our cover page and no doubt the then painter of fashion.

This painting was discovered at Resine, the 24th of March 1746. The rest of our collection are head-dresses copied from medals. On them we see heads adorned with the mitre and the crescent; they are from the bas-reliefs in the Pio-Clementino Gallery.

Greek women contrived much diversity in the arrangement of their hair; preserving its glorious luxuriance (except when in sorrow or mourning; when they cut it very short), and neglected nothing for the embellishment of that natural adornment.

For the decoration of the head-dress, they made use, either separately or in conjunction, of veils of rich or light materials, of bands of differing colors and of flowers and many perfumes. The hair was curled and dyed. “She was fair-haired, says Lucian. (Dialogue of the Courtisans); and her hair had that color from nature, not from art or such drugs as women make use of.”

WIGS

Wigs were also worn, “entrichon”, “penike”, and “procomium “, were the names given to false heads of hair, worn by men and women without distinction. The penike was the front part of the head or “procomion”, and the entrichon consisted of two parts of hair, or of tufts to be placed on the bald parts.

Young people of both sexes allowed their hair to grow until their adolescence; then they consecrated it to the gods.

Girls generally parted their hair on the forehead, gathered it together and tied it on the top of the head. Women parted it likewise and formed at the back of the head a tuft or knot, sometimes made fast with braids, and funnel-shaped. The figures in ancient style show that, from an early period, simplicity in the matter of head-dress was a mere appearance. The hair was, as may be seen on the pediment in the Temple of Aphaia or Afea (Greek: Ναός Αφαίας), divided into small regular curls around the head. Then it was held by a narrow band falling in a point behind the back; but in order to secure this result, it had been pressed in tongs. The general name of anademata or anadesme was given to all bands serving to fasten and adorn the hair: that of mitre was given them later on, for reasons hardly known; perhaps because or their shape.

The “nimbus” was a band of flaxen material adorned with gold embroidery, which women wore around their forehead in order to make it narrower and to make themselves appear younger. “Frons minima” was looked upon as a beauty, a high forehead being an attribute of old age which denudes the temples.

SPHEDONE

The sphedone was a fillet for holding the hair. It was broad in the middle and gradually grew narrower like the sling, whence its name. The broad part was first set in front and the narrower part fastened at the back of the head. The women used “vesica” or bladders with which they kept their hair neat by wearing them over their heads. They wore them at night and took them oH’ again when they dressed their hair. The women also wore caps which took after the older head-dresses in some of their peculiarities. They wore a pearl necklace and in their ears the triglenes, called by the Athenians” triotides” which is contrary to its assimilation to the vesica. It is more like the mitrella or small mitre; a pointed headgear also worn by men at home and at table, and which Cicero asserts he has seen worn in Naples by young and old men of the highest rank. It has also been found in Pompeii.

Source: Paul Louis de Giafferri. The History of the Feminine Costume of the World. The Beautiful Lines of the Greek Costumes. Published: 1926.