The Nightless City. Geisha and Courtesan Life in Old Tokyo by J. E. de Becker.

The History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku.

Mei-gi ryaku-den.

Brief sketches of the lives of famous courtesans

by J. E. de Becker.

Takao.

The first Takao flourished in the period of the former (moto) Yoshiwara, and was called Myōshin Takao. She was also known as Ko-mochi Takao (child-bearing Takao) as she used to promenade attended by a wet-nurse who carried the child of which she had been delivered.

The second Takao

was known as Daté Takao, also known as Sendai Takao or Manji Takao c.1640-1659.

The third Takao

was “Saijō Takao” who was redeemed by one Saijō Kichiyemon (a ratainer of Kii Chūnagon) and taken by him to his native province (Kii). Another account says that she was redeemed by Saijō Kichibei, a gold-lacquer painter at the Shōgun’s Court.

The fourth Takao

was called “Asano Takao” It is said that she was redeemed either by Asano Iki-no-Kami or Asano Inaba-no-Kami, both of whom were dainmyō *). According to the list of dainmyō published in the 4th year of Meireki (1658), Asano Iki-no-Kami seems to have been the grandson of the well-known Asano Nagamasa.

*) Daimyo (Japanese: だいみょう Daimyō) was a title given to a larger territorial lord in feudal Japan, derived from the word name lord.

The fifth Takao

was called “Midzutani Takao.” She was redeemed by Midzutani Rokubei, a banker to the Prince of Mito. Later she eloped with a servant of Mizutani—an old man 68 years of age. Then she married Handayū Ryō-un, and next became the concubine of Makino Suruga no Kami (a daimyō), but she again eloped with one of the latter’s attendants named Kōno Heima.

Next we see her as the wife of a hair-dresser at Fukagawa, then the wife of an actor named Sodeoka Masanosuke, and then that of an oil dealer at Mikawa-chō. The career of this much-married woman was brought to a close by her sudden death in the street in front of the Dai-on-ji temple.

The sixth Takao

was called “Da-zome Takao,” and was redeemed by a dyer named Jirobei. She is said to have been a very beautiful woman who surpassed all her predecessors except the fifth, (whose immoral behaviour we have just noticed) to have been a skilful writer (one of the necessary accomplishments of a lady) and to have been of a quiet and gentle disposition.

With her lady-like accomplishments and graceful manner she was fitted by nature to become the wife of a gentleman of position, and yet she married Jirobei although the latter was not only in humble circumstances but noted for being a rare specimen of ugliness. The strange union, however, proved a great success as the pair lived on most happy and affectionate terms.

The history of their marriage was briefly as follows. Jirobei, who was a dyer working in his master’s shop, one day went out to the Yoshiwara with his comrades to see the promenading of yūjo *). On this occasion he first saw his future wife, and, being greatly struck by her beauty and graceful demeanour, he thought if he could only approach her the one wish of his whole life would be gratified.

*) Oiran are prostitutes in the Yoshiwara brothels who are of high rank, known as yūjo (遊女, lit. “woman of pleasure”). Tayū are the highest-ranking courtesan of oiran.

At that time, however, the engagement of so superior a yūjo by a common artisan who made a hand-to-mouth living was, of course, out of the question and Jirobei felt desperate. The matter preyed on his mind to such an extent that when he returned to his master’s house he looked so melancholy and depressed that his appearance attracted the attention of his employer.

Unable to conceal his secret, he unbosomed himself to his master, and the latter encouraged him to work diligently and save money enough to engage the yūjo as it was, after all, only a matter of money.

For more than a year Jirobei worked very hard both by day and night, and by dint of great economy managed to save enough cash to pay the age-dai of a yūjo of Takao’s class. The very moment that he had sufficient money he hurried off to the Yoshiwara, as he feared that should he wait too long the object of his love might be redeemed by somebody and thus be lost to him for ever.

Entering the quarter dressed in his workman’s attire, and looking dirty and uncouth with his unkempt hair and stubbly beard, he experienced considerable trouble in approaching Takao, but finally he succeeded in meeting her and disclosed thing without reserve.

Her woman’s heart was greatly moved by this proof of loving sincerity, and she finally promised to marry him when her term of engagement expired. This promise she afterwards faithfully redeemed, and Jirobei then opened a dyer’s shop on his own account in the city, and became very prosperous in after years.

It seems that Jirobei was not a success as a dyer as he was unskilful in the technique of his trade, but his business prospered on account of the many people who patronised his establishment in order to catch a glimpse of the famous and romantic beauty.

It is not on record as to who redeemed the seventh Takao. Some persons mistake the seventh for “Sakakibara Takao.” In the Mi-ura record the sixth is erroneously mentioned as the “Sakakibara Takao.” The eight and ninth appear to have had successful careers in the Yoshiwara, but they were apparently not redeemed by people of note as no record exists on this point.

The tenth Takao

seems to have appeared in the Yoshiwara either in the 13th or 14th year of Kyolio (1728 or 1729).

The eleventh Takao

was redeemed by Sakakibara-Shikibu-Tayū, daimyō of Takata, Echigo province, who enjoyed an income of l00,000 Icoku of rice per annum. With the retirement of this lord she accompanied him to his clan headquarters (Takata): after his death she became a nun and died at the age of thirty and odd years.

Hana-ōgi c. 1793. Also known as Ogiya Hanaogi 扇屋花扇.

The Yedo-Kwagai-Enkakushi says that the brothel-keeper named Ōgi-ya Uyemon (Ogiya Uemon (扇屋宇右衛門)) was a pupil of Katō Chiin, well versed in the composition of Japanese poems, and favourably known by his literary name of Bokuka (“Inky River”).

Among the inmates of this gentle poetaster’s house was a yūjo named Hana-ōgi who was very popular at that time. About the 6th of Kwan-sei (1794) she escaped from the Yoshiwara and lived with a man with whom she had contracted intimate relations, but she was soon detected and brought back to her master’s house. She then refused, on the plea of illness, to act as a yūjo any more and no persuasion had any effect upon her.

Finally the master of the house composed a poem to the effect that: “Notwithstanding the careful attention given to the plum-tree by it’s care-taker in order that it’s flowers may not be injured the wind increases in violence.” and showed it to her.

Hana-ōgi, bursting into tears, and touched by the kindness of her master, instantly composed another poem which read: “The plum-blossoms that tightly closed themselves in order not to be shaken by a merciless wind may be found in bloom next Spring.”

From this time she changed her mind and her popularity returned. The Kinsei Shogwadan says that Hana-ōgi, a yūjo of the Ogiya Uemon, Yoshiwara, not only had poetical tastes and was well versed in the art of penmanship but was a most filial and dutiful daughter towards her aged Mother.

Though her literary accomplishments were wellknown and recognised, her filial piety was not so widely known, and the author of the Kinsei Shogwadan says “filial piety ought to be prized above all other things. It is a rare quality among women who sell their bodies for prostitution.”

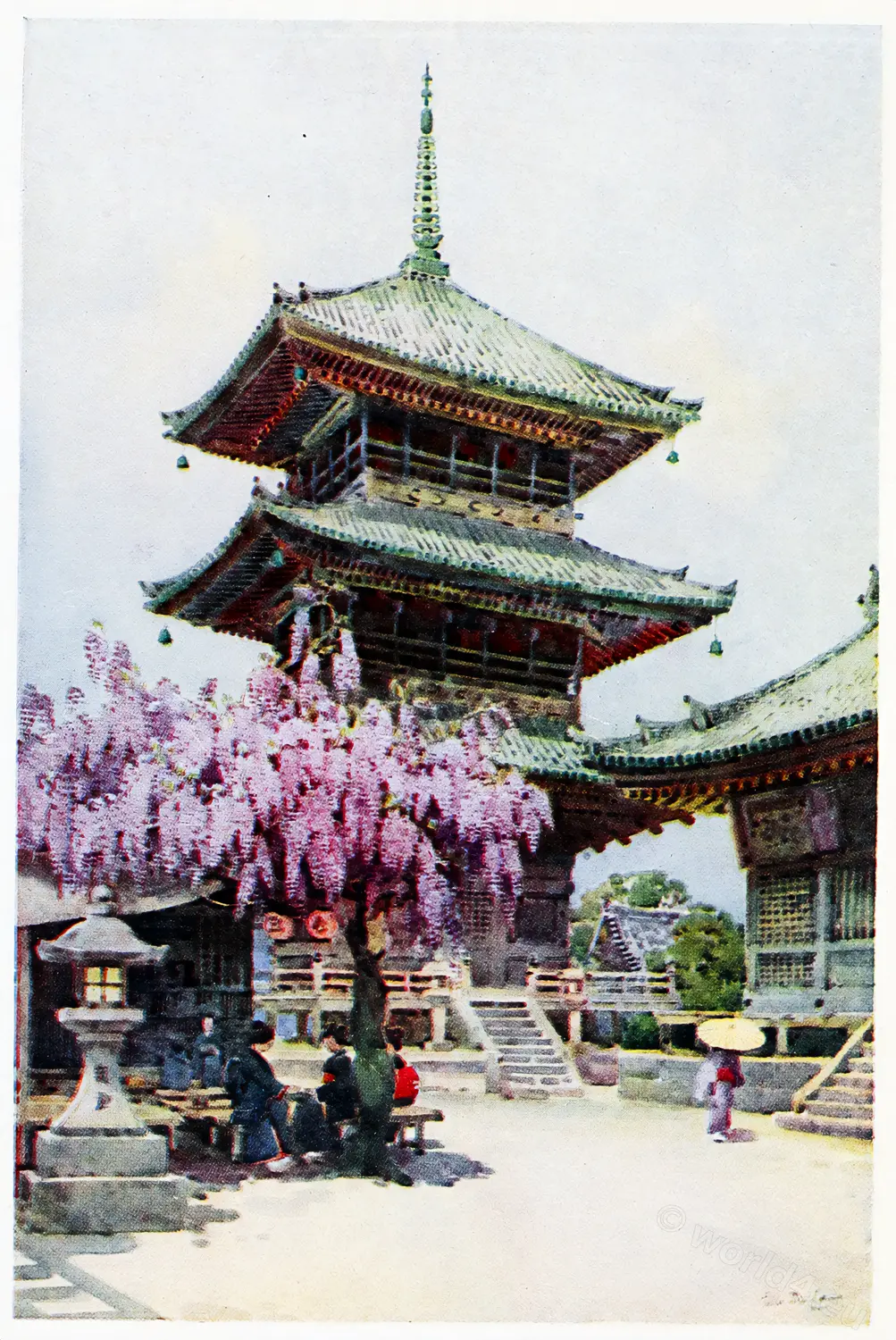

Nakanochō was the main street in Yoshiwara, a famous walled pleasure district that housed as many as 4,000 courtesans. In the early evening, elaborately dressed courtesans accompanied by attendants promenaded on the central thoroughfare, as in this scene.

The open buildings with shop curtains hanging from their eaves are teahouses, establishments where men could arrange appointments with courtesans of the more prestigious brothels. On the left side of the street, an unaccompanied courtesan holding a long, slender pipe lounges on a porch and converses with another courtesan.

At the right, a pair of courtesans attract the attention of two men, one presumably a samurai who wears a hooded cloak and hides his face behind a fan. The open buildings with shop curtains hanging from their eaves are teahouses, establishments where men could arrange appointments with courtesans in the more prestigious brothels.

Source: The Cleveland Museum of Art

In the case of Hanaōgi, her filial piety having been noised abroad until her fame reached even to far away lands, a Chinese scholar, named Hikosei, who visited Nagasaki on board of a trading-ship, happening to hear about her sent her a letter of eulogy written in the style of a Chinese poem.

The composition, which was characterised by beautiful and imaginative thought, may be freely translated as follows: “You, who are the leading courtesan of a superior house of pleasure, are richly gifted by Heaven with a hundred various graceful accomplishment most excellent in woman. I, being a stranger and sojourner from a far-off land, must sail away without beholding your charms, but I shall long for you while tossed upon the bosom of the boundless sea.

There is in Yedo a famous courtesan, named Hana-ōgi, who not only is of unsurpassed beauty, but is well versed in literature. This lady has an aged mother at home whom she adores, and to whom she blindly devotes herself as a filial child is bound to do.

I have sojourned in Nagasaki for a decade and have known many women at once beautiful and possessed of poetic tastes, but never have I heard of a courtesan accomplished in literature and likewise distinguished for her filial piety. Having heard your story —Hana-ōgi— I wish to personally visit you, but this being impossible I compose a poem and send it to you.” [signed] Shokei Hi-sei-ko.

It appears that Hana-ōgi was a pupil of Tōkō Genrin (a poet) and often composed both Chinese and Japanese poems. Three of her compositions run as follows:

1.—The name of Hana-ōgi (“Floral Fan”) does not suit the person who bears it, and is comparable to the case of a rough woodman who has an uncommon and ludicrously fine name.

2.—Though the autumnal moon is shining, the countenance of him upon whom I gazed for the last time in the days of Spring vanishes not from my mental vision.

3.—The moon shines so brightly and magnificently upon the trembling surface of the river that the shadow of a man who is handling ropes in a boat may be clearly discerned.

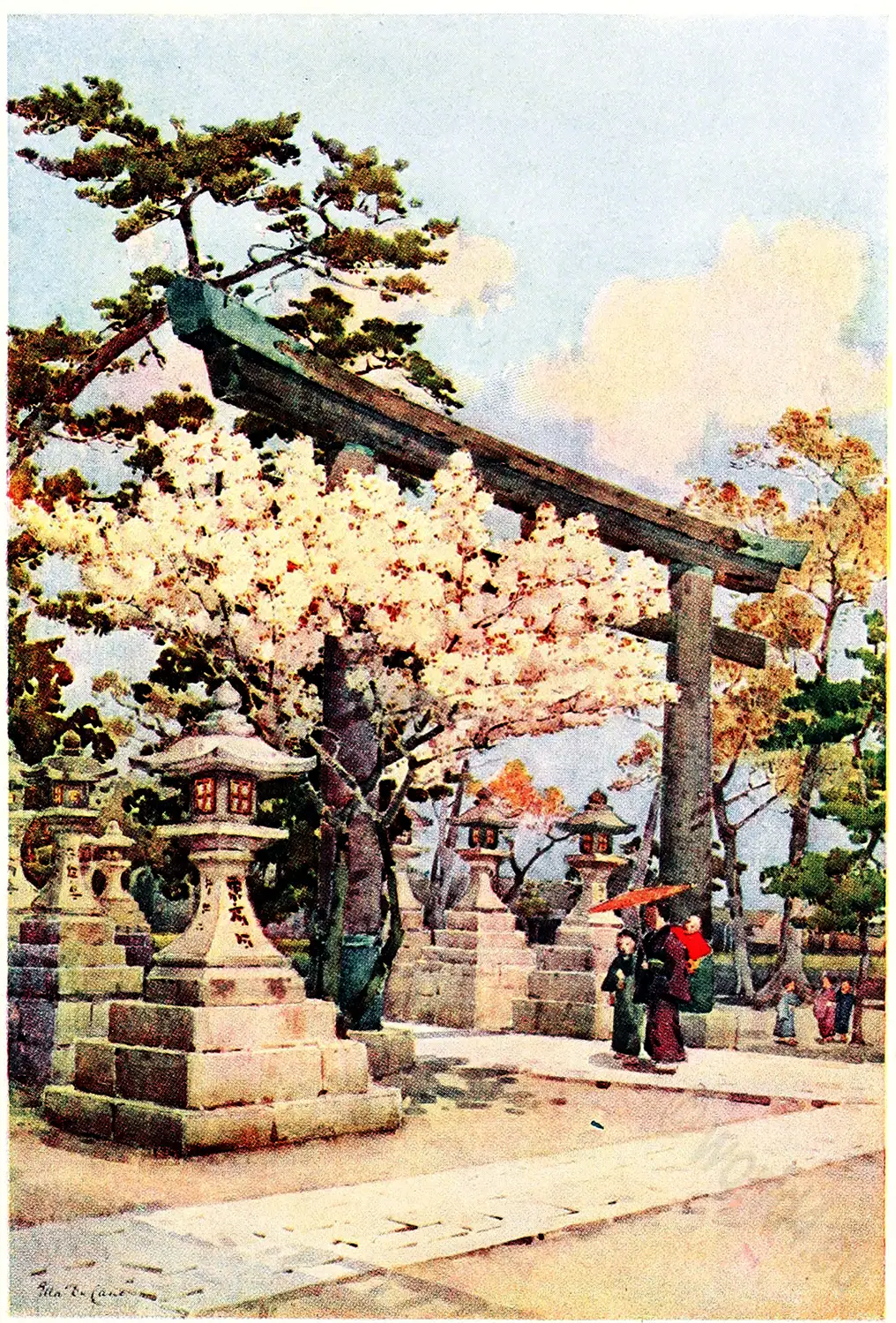

It is said that this noted courtesan wrote the Chinese characters (meikin “tinkling harp”) and after framing the paper presented it to the Ishi-yama-dera (temple) where it was hung in the Genji-no-ma (room). *)

*) The monastery of Ishi-yama was founded in 749 by the monk Riō-ben Sūjō, at the command of Shōmu Tennō. It was destroyed by fire in 1078 and rebuilt a century later by Yoritomo.

The present hen-dō (main hall) was built by Yodo-Gimi, the mother of Hideyori, towards the end of the 16th century. The little room to the right of the hen-dō, known as the Genji-no-ma, is said to have been occupied by the famous authoress Murasaki Shikibu during the composition of her great romance, the ‘Gen-ji Monogatari.’ Ishiyama-dera is famous for the beauty of its maple-trees in autumn. (Murray’s Hand-Book of Japan.)

Tamakoto.

In one of the poems of the famous Basho it is said: “The pine-tree of Karasaki is more obscure than the flowers.” This poem is considered to be written in praise of the virtue of the evergreen solitary pine-tree which is inferior to the flowers on a cloudy night.

Tamakoto may be favourably compared to this pine-tree of Karasaki (which is a universally recognised symbol of virtue) as she is described to us as “a model of sincere, charitable, and charming womanhood, whose graceful manner and delightful conversational power lifted her high above the other women her class.”

Owing to these unique and sterling qualities she became the most popular of all the courtesans of the Yoshiwara. The custom of depositing a leaf of a “naki” tree in the back of the handle of the mirrors, used by ladies in making their toilettes, was inaugurated by Tamakoto, it was afterwards followed by many ladies of high rank.

In feudal days the sword was called “the living soul of the samurai” and a lady’s mirror was also considered as equally precious and important to her. The depositing of a leaf of the “naki” tree in the mirror handle appears to have had a religious significance, as the naki tree is said to have been the sacred tree of the shrine of Idzu Dai-Gongen, in Hakone, Idzu province.

It was believed that the Hakone Gongen was the deity who supervised the carrying out of promises made between the sexes, and therefore the naki leaf placed within the mirror handle was equivalent to a pledge to the gods that the owner of the mirror would be faithful to men and never utter a falsehood.

While she was yet in the prime of life Tamakoto fell sick and returned to her parents’ home, where, in spite of everything done to restore her to health, she departed this life and “set out on her journey to the unknown world” in the 25th year of her age.

During her life this accomplished woman composed a lyric song entitled “The sorrowful butterfly” which was afterwards set to music by Ranshu and sung in loving memory of the gentle authoress.

Katsuyama.

In the employ of Yamamoto Sukeye-mon, of Kyō-machi ni-chō-me, was a yūjō named Katsuyama who, though a sancha-jorō, was a gentle and kindhearted woman, accomplished in the art of composing Japanese poems and very aesthetic in her nature.

Once, on the occasion of the celebration of a hina-matsuri in the third month of a certain year, a well-known poet of that age —Ransetsu—happened to be in Katsuyama’s room and witnessed her preparations for the festival, and he wrote the following stanza: “It is pitiable to see a barren woman celebrating the hina festival.”

This is in allusion to the fact that the doll-festival (hina-matsuri) was originally inaugurated for the purpose of celebrating the birth of children and of manifesting a desire to have a succession of lineal descendants to perpetuate the family name.

It means young birds newly hatched from the eggs, and in feudal times child-bearing was considered of such great importance that barrenness was a sad disgrace and formed a legitimate ground for divorcing a wife.

A courtesan, in consequence of her unnatural life, and the physical strain to which she was subjected, was supposed to be incapable of conceiving, and hence Ransetsu’s lament that a women of Katsuyama’s goodness and beauty should be condemned to celebrate a festival which amounted to a mere mockery of her unfortunate position.

Though a courtesan, Katsuyama was a sincere and worthy woman, an earnest and devout Buddhist, possessed of refined tastes which made her a lover of the beautiful, an adept in floral arrangement, and an accomplished writer.

She also seems to have been gifted with an inventive genius for she devised a unique style of hair-dressing which was so simple and unaffected that it speedily found favour with every class of women, not excepting the ladies of the daimyos’ courts, the latter adopting this coiffure almost universally. It is still known as the “Katsuyama magé”.

A very pretty story is told which illustrates the kindness of heart that characterised Katsuyama. There was a certain Bugyo, named Kaisho, who was on intimate terms with the fair dame and who was so infatuated with her goodness and beauty that he spent considerable sums of money in the purchase of rare and costly articles for the purpose of affording her pleasure.

On one occasion he sent her a silver cage, fitted with a golden perch, containing a beautiful Korean bird, known as a hiyo-dori (brown-eared bulbul). When he sent her this present he remarked that it was impossible to buy such a bird with money, and that he had only obtained possession of the pretty warbler owing to his position and influence as a bugyo.

Katsuyama was delighted to receive the kind gift of her friend, but after she had exhibited it to the inmates of her house she took the cage into her own room and addresed the feathery inmate in the following words:

“Sweet little birdie, there may be those who envy your position living in a cage decorated with gold and silver and being petted by people, but I, my birdie, know that the thoughts which fill your mind are quite opposite to those others attribute to you. I have lived for many years in the Yoshiwara like a bird in a cage and can sympathize with your situation.

I too have lived in a golden cage and am arrayed in gorgeous robes, but I know that a person deprived of freedom is like Ōshokun *) for whom jewels and flowers had no attraction and who felt as if living in Kikaigashima (devils’ island).

Judging by my own feelings I can imagine the sorrow of you, birdie, for be you ever so well treated and carefully tended you will flutter against the bars of your cage and long to fly away and be at liberty under the blue sky of Heaven just as I long to return to my dear native place”.

*) Wife of an ancient Chinese King who was held by the enemy as a hostage in a foreign country.

So saying, Katsuyama took the beautiful bird from its cage and allowed it to fly away. If this had happened in the time of Kenkō Hōshi (the priestly author of the Celebrated Tsurezure-Gusa) he would assuredly have praised her kindly deed in the same manner as he did a similar act of Kyōyū in his well-known book of jottings.

Segawa.

The second Segawa of the Matsuba-ya of Yedo-chō ni-chō-me (Yoshiwara) was redeemed by the master of E-ichiya (an establishment in the vicinity of Ryōgoku-bashi, and the third Segawa by a blind musician named Toriyama.

The second Segawa lived on affectionate terms with her redeemer, but by and by she fell sick and lay helpless for a long time in spite of everything which her doctor could do.

Some person having suggested that if she were named after an animal she would recover, Segawa changed her name to Kisa, (archaic term for “elephant”) and tradition says that after this she was gradually restored to health under the treatment of a certain Doctor Kitayama Gian.

While Segawa was still in the Yoshiwara she sent a letter, written in a beautiful hand, to her intimate friend Hinadzuru (of the “Chōjiya”) on the occasion of the latter leaving the Yoshiwara in consequence of having been redeemed by a guest.

The letter was a model of Japanese feminine writing, and ran as follows:

“It is with feelings of the utmost satisfaction

“and delight that I hear you are to-day going to

“quit the “house of fire” (Kwa-taku) of this

“Yoshiwara for ever, and that you are going away

“to live in a cool and more congenial city. I

“cannot find words adequate to the task of express-

“ing my envy of the promising future which awaits

“you at your new residence. Moreover, according

“to the principles of divination, your nature has

“affinity with wood while that of your husband

“has affinity with earth. This is an excellent

“combination of the active and passive principles

“of nature, for the earth nourishes and protects

“the wood (tree) as long as it lives. This is indeed

“a good omen and augers well for your future pro-

“sperity and happiness, and I therefore again

“congratulate you on the felicitous and promising

“union you have made.”

Usugumo (Faint Clouds)

In the Genroku period (1688-1703) Usugumo (Tamaya uchi Usugumo) was one of the most popular of the Yoshiwara courtesans and ranked next to Takao in this respect. She was an exceedingly beautiful woman, graceful and slender as a willow-tree, and moreover she was versed in all those polite accomplishments the acquirement of which is necessary to a Japanese lady.

On the 15th day of the 8th month of a certain year she was holding a “moon-viewing” party with her guest in the second story of an “ageya” and was busily composing or reading Japanese and Chinese poems while enjoying the ravishing splendour of the full harvest moon which hung like a glittering silver mirror in the cloudless autumnal sky.

Presently thin clouds appeared on the horizon, and gradually spreading themselves over the heavens screened the moon from view. In the adjoining room a Kōshi-joro named Matsuyama (“Pine Mountain”) was also holding a moon-viewing” parly with her guest, and this woman, not being on good terms with Usugumo (“Thin (or “Faint”) Clouds”) maliciously remarked: “The thin clouds are insolently hiding the beauteous moon from public gaze.”

Hearing this but ill-veiled sneer directed at herself by means of a clever play upon the words “uso-gumo” (faint (or thin) clouds) Usugumo, unable to control her temper, replied with cruel directness: “Those thin clouds which now obscure the moon may appear to be blots on the sky above us, but after all they are but transient and will soon drift away.

The pine-crowned mountain (Matsu-yama) yonder, on the contrary looms up dark- and forbidding in the landscape and permanently obstructs the best view of the orb of night.”

Discomforted by this spontaneous and fitting answer, Matsuyama coloured up and immediately retired from the party. Usugumo was well-known for her ready wit and cleverness in repartee, and the above incident proves that her reputation was well deserved. Usugumo possessed a beautifully furred cat which she was accustomed to take with her whenever she went out promenading, the animal being carried by one of her attendant Kamuro.

Strange to say, whenever Usugumo went to the lavatory her pet followed her without fail, and this fact having become well known among the inmates of the house it gave rise to an idle whisper to the effect that the cat was in love with its owner!

The proprietor of the “Miura-ya” (to which establishment Usugumo belonged), hearing of this story, one day caused the cat to be fastened to a pillar and awaited the result. On seeing Usugumo going into the lavatory, however, the cat became desperate, and biting through the rope with which it had been fastened attempted to rush after it’s mistress, leaping clean over a pile of kitchen utensils which stood in the way.

As it flew along, one of the cooks gave the animal a blow on the neck with a sharp kitchen knife, completely severing poor pussy’s head from her body. Usugumo, who had been in the lavatory, being frightened by the noise and comkmotion, came hurriedly out and was much distressed to find her cat dead, but she noticed that although the body remained the head of the unfortunate animal had disappeared.

On an examination of the lavatory being instituted, the missing head of the cat was discovered with its teeth tightly closed in a death grip on the throat of a great snake which was writhing in the throes of impending dissolution!

Then the mystery of the cat’s constant attendance on it’s mistress was fully explained as the people saw that the unhappy animal, knowing of the snake’s existence, had followed Usugumo for the purpose of protecting her from injury, and had died in her defence.

When the story of the cat’s faithfulness became known everyone bewailed pussy’s sad fate, and in order to atone for the cruel treatment to which it had been subjected the animal was buried in the family cemetery of the house. Kikaku’s poem to the effect that:

“The cat of Kyōmachi was wont to play

“between it and Ageya-machi”

Seems to refer to Usugumo’s pet.

In former days the grave of this loyal creature was pointed out at Ageya-chō, but nowadays the site of the monument has been forgotten owing to the frequent occurrence of fires in the Yoshiwara.

Ōsumi.

Though Ōsumi was comparatively lower in rank than Shiragiku of the “Yama-gata-ya” and Karyū of the “Hyōgo-ya”, she was a very popular courtesan and more sought after than they.

One day she was suddenly taken ill, and her malady increasing in severity she could get no rest even at night. When, worn out with fatigue she finally succeeded in dropping into a fitful slumber, she dreamed of things so horrible that she shrieked and groaned in an agony of terror, while the cold sweat poured in a profuse stream from her quivering frame.

Her symptoms were so dreadful that the other inmates of the brothel felt their blood run cold as they gazed on her drawn and terror-stricken countenance and heard her awful cries of fear, but they did their best to alleviate her sufferings and attended her assiduously.

Curious to relate, the women who nursed the unhappy sufferer found an immense toad at the side of her couch, and although they flung the loathsome creature away several times it would immediately return and squatting down by the bed would sit gloating over the patient— a portentous and revolting watcher!

At length, notwithstanding the efforts of her attendant physician, Ōsumi wasted to a skeleton and finally died of the dread disease which had seized upon her, but to the last she uttered the most ghastly and blood-curdling cries and in her delirium expressed a sense of the most awful terror pursuing her to the grave.

It is stated that a certain priest had been in the habit of frequently visiting Ōsumi, and having fallen in love with her tried his best to win the fair courtesan for himself, but failed owing to her having a paramour. The latter had squandered his parent’s money in riotous living and had been driven out of his home on that account.

Ōsumi, in order to assist her sweetheart in distress, pretended to be deeply in love with the priest referred to, and by this means inveigled the recreant “Servant of Buddha” into supplying her with considerable sums of money, all of which she promptly gave to her secret lover.

One dark night, the deluded priest was foully murdered on the banks of the Nihon-Zutsumi, and it is said that his troubled spirit sometimes passed into the body of a frog which sat haunting the bedside of Ōsumi, and at other times took possession of the body of a kamuro and in a hollow sepulchral voice expressed his resentment to the heartless woman who had allured him to death and perdition.

Komurasaki (Little Purple, the second of the name).

The name of this courtesan is known throughout the length and breadth of our Empire, and the fame of the fair girl has been spread even to Western lands by means of a story entitled “The Loves of Gompachi and Komurasaki” given in “Tales of Old Japan”.

She is regarded as a specimen of feminine faithfulness as exhibited by women of her class. She was proficient in the art of literary composition, wrote a beautiful hand, and was well versed in all those other graceful accomplishments which were considered necessary to ladies in this country.

It is said that she was the authoress of a popular song called the “Yae-ume” (The double-blossomed Plum) which ran as follows: “I am like the azalea which blossoms in the meadows: pkick my flowers ere they fall and are scattered. I am like the firefly in the field, which lights up the bank like a pine-torch.

However impatiently I may long for you and pine to meet you I am like a bird imprisoned in its cage and cannot fly away, and my inexpressible sorrow makes me brood in melancholy”.

The touching story of the loves of Ko-Murasaki and Shirai Gompachi is as follows: “About two hundred and sixty years ago there lived a young man named Shirai Gompachi who was the son of a respectable samurai in the service of a daiinyo in the central provinces. He had already won a name for his skill in the use of arms, but having had the misfortune to kill a young fellow-clansman in a quarrel over a dog he was compelled to fly from his native lace and seek refuge in Yedo.

On arriving at Yedo he sought out Bandzui-in Chobei, the chief of the Otokodaté (Friendly Society of the wards-men of Yedo) and was hospitably entertained and protected by that famous wards-man.

One day Gompachi went to the Yoshiwara for the first time in company with Tōken Gombei, Mamushi Jihei and other protéges of Chōbei, and this visit was the cause of his undoing. While watching the gaily dressed courtesans promenading in the Naka-no-chō, escorted by their male and female servants, Gompachi’s attention was drawn to a famous beauty who had recently made her debut in the Yoshiwara.

It was a case of mutual love at first sight, and from that time the handsome young man went daily to the Yoshiwara to visit Ko-Murasaki. As was usual with a frequenter of the quarter, Gompachi, being a rōnin and without any fixed employment, had no means of continuing his dissipation and at last when his stock of money ran out he commenced to resort to robbery and murder for the purpose of replenishing his purse.

Blinded and infatuated by his love for Ko-Murasaki, he continued his wicked course of life and kept on slaying and robbing; but at length he killed a silk-dealer on the banks of Kumagaya and robbed the unfortunate man of three hundred ryō, and this act subsequently led to his arrest and execution as a common felon at Suzuganiamri (“Bell Grove”) near Ōmori which was the execution ground in the days of the Tokugawa Government.

When Gompachi was dead, Bandzui-in Chobei obtained the remains from the authorities and interred them in the burial ground of the Boron-ji Temple at Meguro. Ko-Murasaki, on the other hand, was redeemed by a certain wealthy man after her lover’s death, but on the very night of her redemption she escaped from her benefactor’s house and after spending the night somewhere she repaired the next morning to the temple where Gompachi lay buried.

First she thanked the priest in charge for his kind consideration and care for the soul of the departed, made an offering of a bundle of costly incense-sticks and ten ryō to the temple, and placed five ryō in the hands of the priest asking him to expend the money in erecting a stone monument over Gompachi’s grave.

After this she went out into the burial ground and offered prayers over the tomb of her loved one, and committed suicide by means of a dagger she had brought with her for the purpose. When the chief priest of the temple — Zuisen Oshō — heard what had happened lie reported the sad event to Bandzui-in Chōbei, and the latter soon came to the spot bringing with him the parents of the unfortunate girl.

Unhappy in their lives, in death at least they were not divided, for the body of Ko-Murasaki was buried in the same grave as that of Gompachi.

Beside the tomb was planted an orange-tree with two-branches as a symbol that the two sleepers had entered into their eternal rest in perfect and mutual accord, and over the grave they erected a stone monument on which were engraved the respective crests of the couple — a sasarindō *) in the case of Gompachi and a circle containing two characters in the case of Ko-Murasaki.

*) A family badge in the form of a tuft of five overlapping bamboo leaves with their apexes spreading downwards, and surmounted by three little flowers.

The names of the dead pair were also inscribed on the tombstone, and the words “Tomb of the Hiyoku” added. The monument remains to this day, and by it stands another bearing the following legend: “In the old days of Genroku, she pined for the beauty of her lover, who was as fair to look upon as the flowers; and now beneath the moss of this old tombstone all has perished of her save her name”.

Amid the changes of a fitful world, this tomb is decaying under the dew and rain; gradually crumbling beneath its own dust, its outline alone remains. Stranger! bestow an alms to preserve this stone, and we, sparing neither pain nor labour, will second you with all our hearts.

Erecting it again, let us preserve it from decay for future generations, and let us write the following verse upon it: “These two birds, beautiful as the cherry-blossoms, perished before their time, like flowers broken down by the wind before they have borne seed.”

While Gompacbi was in prison the following letter was sent to him by Ko-Mura- saki: “I am looking upon the rare flower, which yon sent to me only the other day, as if I were gazing upon your conntenance. I am extremely distressed to learn that you find yourself placed in such an unpleasant position, and am inconsolable at the thought that your unhappy plight has been caused by myself. I hear it stated that there is a god even in the leaf of a flozver and so I solemnly appeal to this diety to witness my unaltered faithfuhlness and constancy towards you come what may.”

The above document is still in existence and is known as the “Hana-kisho” (the Floral vow); it is often quoted to show how Komurasaki loved her sweetheart and how faithful and true she was towards him in the day of adversity.

Even to-day people think kindly of the sorrows and constancy of the beautiful courtesan and keep her memory green in song and story, and still pious folks burn incense and lay flowers before her grave and say a prayer for the souls of the ill-fated couple.

A popular song expresses the feelings of the Japanese people towards Ko-Murasaki when it says : “Who shall say that courtesans are insincere? Let him visit Hiyoku-zuka wich bears silent but eloquent testimony to a courtesans fidelity!”

Kaoru (Fragrance)

Kaoru was an exceptionally beautiful woman and was the leading courtesan of the “Tomoye-ya.” A certain enthusiast has left a record of the impression made upon him by this belle in the words— “Everyone who gazed upon her lovely countenance and noted her charming and graceful mien was intoxicated with the joy of her presence and remembered the story of the historical Chinese beauties Rifujin and Seishi.

Once, one of her familiar guests brought her a water-vessel containing” four or five much prized gold fish of a specie known as Ranchō.

Kaoru and the other inmates of the house were greatly delighted with the beautiful gold-fish, and surrounding the vessel looked eagerly into it, quite forgetting in their excitement that they were neglecting their visitor. By and by the guest became weary of waiting, and to beguile his tedium he also edged his way into the group of on-lookers to see what was going on.

He perceived a maid-servant, under the directions of Kaoru, taking the gold fish out of the vessel one by one and placing them on the cover of the latter. This proceeding aroused his curiosity and he enquired the reason saying: “Why do you take the fishes out of their element? None of them are dead”! Kaoru blandly replied —”The fish seem quite tired, so I am giving them a rest by making them lie down on this cover.”

The guest was dumbfounded at this marvellous exhibition of unadulerated ignorance and burst into laughter. This story may seem to reveal most crass ignorance and a wonderful depth of idiotic stupidity but in those days such an exhibition oif want of information on common topics was greatly appreciated in Japan, for it was supposed to betray maiden-like innocence of the World.

At any rate, it is said that Kaoru’s guest was so struck with her simplicity that he became more attached to her than ever alter this event. There is another highly disgusting and somewhat Rabelaisian story narrated about Kaoru which is supposed to show the affection [sic] in which this charming courtesan was held in the Yoshiwara.

A party of reckless young bloods were holding a sake party one night, and the liquor was flowing freely, when suddenly some stupid individual dared any person in the assembly to swallow the contents of a large cup filled with pepper. Flushed with wine, and ready for any devilment, another human ass immediately accepted the challenge and volunteered to undertake this feat of horrible gormandizing.

First the enterprising idiot drank a cupful of sake and then proceeded to gulp down the pungent preparation; but no sooner had he swallowed the first mouthful of pepper than he fell down writhing in terrible anguish, his eyes starting from his head, and his countenance revealing the tortures of the damned in the

burning hell.

Naturally a scene of great confusion followed this occurrence, the party was sobered up by the untoward event, and a doctor was immediately summoned to treat the patient.

This disciple of Æsculapius was apparently as well posted about medical affairs as an ordinary coolie, for he was at his wits end to know how to treat the case. However, something had to be done to keep up the reputation of the “faculty,” and the worthy leech gravely prescribed human feces as a medicine possessed of remarkably curative properties!

This abominable prescription frightened the attendants, and they decided to ask the patient for his opinion on the matter. The latter, being unable to speak, seized a brush and wrote down on a piece of paper— “If I must perforce take the horrid dose, I prefer * !!!

Kokonoye (Nine-folded.)

Kokonoye was the name of a wellknown courtesan who was possessed of considerable literary ability. Her story is a sad and withal interesting one as it reveals the vein of illogical reasoning traversing the unnecessarily severe and inhumane judgments of the Japanese judicial authorities in ancient times.

It appears that Kokonoye had been in the employment of a certain respectable citizen of Tokyo as wet-nurse for his infant son. By and by the child grew older and one day, while playing, he got drawn into a quarrel with one of his comrades.

Words soon led to blows and the boy inflicted an injury on his little playmate which caused the death of the latter. The dead boy’s parents, indignant at the deed, complained to the authorities and the case came on for hearing before Oka Echizen no Kami who was renowned as a great jurist in the olden days.

The Solomon- like Judge decided that both the little prisoner and Kokonoye were alike guilty. He said that the boy had actually committed homicide and that the nurse had been an accessory to the crime inasmuch that she had failed to exercise proper control over her charge.

The boy was therefore sentenced (due consideration being had for his tender years) to be sent to a monastery and trained as a priest, while the unfortunate nurse was condemned to a life of shame in the “Sea of bitter misery” (the “Yoshiwara”) for a term of five years.

Kokonoye was accordingly sent to the Yoshiwara and was there engaged as a courtesan in the “Nishida-ya” at Yedo-chō, It-cho-me.

Another account says that this woman originally belonged to the family of a Kyoto citizen, but that owing to her lewd conduct she was sent to the Yedo Court for trial and there sentenced to perpetual service as a courtesan in the Yoshiwara.

That she was a woman of literary and poetical tastes some of her compositions testify; especially one poem in which she feelingly refers to her native place, her banishment, the three great duties of women, and the five obstacles against women attaining the joy of Nirvana.

Years rolled by, and, on account of her age, Kokonoye was no longer able to retain the popularity which she had originally enjoyed. Accordingly in the Kyōhō era (1716-1735) the nanushi and elders of Yedo-chō proceeded to the Court and prayed for the commutation of Kokonoye’s sentence on the ground of her age, but the petition was rejected.

On hearing this, the poor woman was overcome with the most bitter grief and composed a poem which may be translated thus:- “Alas I am doomed to live in a place far from my parents’ home, and to ladle up forever the water of the never-ceasing stream of the Sumida river.”

On reading this sad poem the nanushi’s pity was intensified a thousand-fold, and with moist eyes he brought the lines to the officials of the Bugyō-sho and again begged for the writer’s liberty.

Greatly moved by this expression of hopeless misery, the authorities were graciously pleased to show their clemency to the unfortunate courtesan, and readily granted the nanushi’s second petition.

Source:

- The Nightless City: or, The “History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku” by J. E. De Becker (1863-1929). Publisher Yokohama: Max Nössler & Co.; London: Probsthain & Co., 1905.

- Japanese colour prints and their designers, by Japan Society (New York, N.Y.), 1913.

- A handbook for travellers in Japan, including Formosa by John Murray (Firm); Chamberlain, Basil Hall, 1850-1935; Mason, W. B. New York, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

- Legend in Japanese art; a description of historical episodes, legendary characters, folk-lore myths, religious symbolism by Henri Louis Joly. London; New York: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1908.

- On collecting Japanese colour-prints; being an introduction to the study and collection of the colour-prints of Ukiyoye school of Japan. Illustrated by examples from the author’s collection by Basil Stewart. New York, Dodd, Mead & company, 1917.

- The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art

- The Walters Art Museum

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.