The Ardabil carpet (also Ardebil carpet; Persian قالی اردبیل) is a famous Iranian Persian carpet from the 16th century and at the same time the oldest carpet in the world with a specific year of manufacture. It was made in two copies, which show very different states of preservation. They are in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in Los Angeles.

The two carpets were commissioned by the Safavid ruler, Shah Tahmasp I. (1524–1576). He wanted to dedicate them to the shrine of one of his ancestors, the Sheikh Safi d-Din Ardabili, in Ardabil. The carpets were completed in 1539-40 and shortly afterwards, on an unknown date. Older dated carpets are not known.

These two carpets are the most important Persian carpets created in Iran. It was therefore inevitable that they were copied almost endlessly in all variations of carpet knotting. A so-called ‘Ardabil’, for example, now adorns the residence of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at 10 Downing Street.

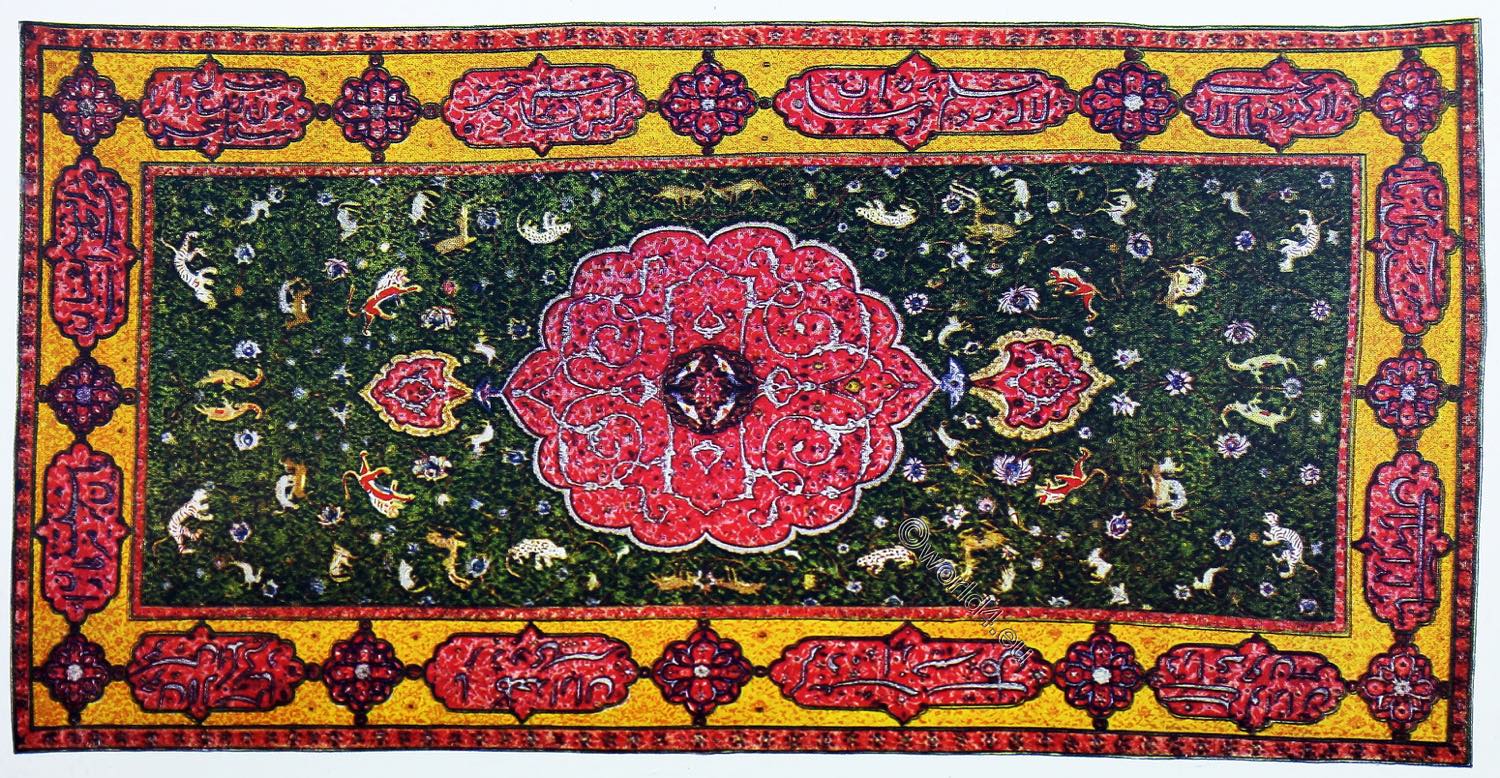

PLATE I.

THE HOLY CARPET OF THE MOSQUE AT ARDABIL.

Dimensions, 34 ft. 6in. x 17 ft. 6 in. Design: a floral tracery on a shaded ground of deep blue, relieved by a bold central medallion of pale yellow, in which the cloud design in light blue is shown in various forms, while the immediate centre is filled by a smaller medallion, also on a light blue ground, brom the outer edge of the large medallion spring sixteen cartouches of varied coloring, and from two of these, again, in the direction of the ends of the carpet, hang two of the sacred mosque lamps. Quarter sections of the central medallion form the angles. On a separate cartouche at the top of the carpet, within the border, is the following inscription in bold black characters, on a cream ground:—

“I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold,

“My head has no protection other than this porchway,

“The work of the slave of this Holy Place,

“Maksoud of Kashan,

“ in the year 942.”

Border: a very delicate floral tracery on a rich ground of brown, relieved by a series of alternate elongated and rounded cartouches, filled with floral and other tracery, the former on a red, the latter on a green or yellow ground. On the inner side of this border a bold band of cream, seven inches wide, exhibiting a formal treatment of the cloud pattern in red, and a narrow band of crimson, separate it from the centre of the carpet, while a similar band seven inches wide, of tawny brown, varying from light to dark, and relieved by a bold scroll work in light blue, frames in the whole design.

Hand-tied knots to the square inch, 380, or 33,000,000 for the whole fabric.

Place of origin: Ardabil or Kashan.

Date: A.D. 1535.

A full account of this carpet is given on pages 5-7, but as the following extract from Curzon’s “Persia” confirms the view taken of the importance attaching to Ardabil and its Mosque at the time when the carpet was woven, it may not be without interest to quote it:—

“Ardabil was elevated into the first rank of Persian cities as the residence and last resting place of the famous saint Sheikh Sefi-ed-Din, the direct descendant of the seventh Imaum and contemporary of Timour. In the fifth generation from him came Shah Ismail, the founder of the Sefair dynasty, who first established his power and was finally interred as sovereign of all Persia in Ardabil. No wonder that two sepulchers so holy should, throughout the duration of the Sefair dynasty, have attracted to Ardabil a host of pilgrims and have conferred upon it the distinction almost of a royal city.

“In a decayed and crumbling Mosque the tomb may yet be seen. In the main hall of the same building, behind silver gratings and a golden plated gate, is the tomb of the Sheikh overlaid with costly carpets and shawls. An adjoining hall contains a superb collection of old faience, principally china vases, the offering of Shah Abbas.

PLATE II

THE ARDABIL MOSQUE CARPET.

THE CENTRE MEDALLION AND THE TWO LAMPS.

Drawn to one-fifth scale.

Ot the many interesting details of the design of the centre piece the varied treatment of the “cloud” is most noticeable. In four instances the figure is given in its normal development. I refer to the four that encircle the small central medallion on a pale blue ground. Four more, bearing on the circumference, are equally regular in form, but these are bound in the centre by a graceful band or knot, while the intervening spaces arc filled by eight others of the conventional type commonly found in the decoration of Chinese vases. It is interesting to note that the special treatment of this figure, in the second series referred to, is that adopted for the decoration of the centre member of the border of the small contemporary carpet, also from the Mosque of Ardabil, illustrated on Plate IV.

The bold scroll decoration in greenish blue, edged with red, is very effective, and gives a marked character both to the centre and angle medallions. Persian designers appear to have introduced it freely where breadth of treatment was required, as may be seen in an example at the South Kensington Museum, labelled “ A painted copy, size of the original, portion of wall tile decoration at Isphahan.”

The two Mosque lamps, introduced into the design with consummate skill, point clearly to the sacred purpose for which the carpet was intended. The delicacy of treatment in their decoration is astonishing, and one may almost imagine that specimens of the famous enameled glass itself are before one.

Marvelous as is the accuracy displayed by the weavers in working out the details of the design of this wonderful carpet, still there are not wanting traces of the irregularity often found in Oriental art.

The lamp figured on the right of the Plate is a good example. This was the first lamp introduced, and although the want of symmetry clearly seen in the drawing, against the plain background, is by no means so apparent in the carpet itself, still it had not escaped the notice of the master weaver, nor was the irregularity forgotten. Years must have elapsed before the second lamp had to be woven, but then Maksoud of Kashan surpassed himself and produced the perfect specimen shown on the Plate at the left of the centre medallion.

PLATE III.

THE ARDABIL MOSQUE CARPET.

Corner Section and Inscription.

The scale of the drawing given on this Plate is one-sixth.

The general details of the whole design, with the exception of the lamps, are here represented with an accuracy that recalls the very feeling of the carpet itself. The outer member of the border, apart from the boldness and freedom of treatment displayed in the execution, is especially interesting. I have given on Plate VII, figure 9, a section of this border, while figure 10 gives the motive of the design. Figure 11 on the same Plate is a section of the inner member of the small contemporary carpet, the subject of Plate IV., while figure 11 B.B. shows the separate details of this inner member. Dissimilar as is the general effect, the design is the same. It must be remembered that both these carpets date from nearly four hundred years ago. Figure 8 of the same Plate is taken from the border of a carpet about one hundred years old, and is again the same design, as an examination of figure 8 A.A. will show.

Finally, figure 12, although taken from a carpet border of some sixty years ago, is the prominent feature of most carpets of the Herati design still woven at the present time. The identity of figure 12 of to-day with figure 10 of four hundred years ago is most interesting, and it may not be out oi place here to point out that the general outline of this recurring form bears a striking analogy to the skeleton bull’s head introduced freely in classical architecture as the ornament of the Metope.

The decoration of the angle is practically the same as that of the centre medallion, but it will be noticed that the cloud forms are dispensed with.

The inscription cartouche is introduced with great skill, and is in itself an ornament. It is well known that calligraphy was an art highly esteemed by the Persians, one that even princes and rulers have been proud to excel in, having first adopted it in compliance with the Mohammedan law which requires every man to be acquainted with some art, or means of earning a livelihood, in case of need. Dr. Wills, indeed, states “that a single line by a great calligrapher was worth a fabulous amount, and that large sums were often paid for a good manuscript of Hafiz or the Koran,” but he adds “that printing has destroyed all this, and that calligraphy as a high art is dying the death.”

The changing shades freely introduced, both in the dark blue ground and in the various decorative details of this masterpiece of weaving, call for a few remarks.

It is well known that the Eastern weaver dyes his wool from day to day—uses now white wool, now brown or tawny, as the case may be; and from this carelessness or necessity it is frequently argued that the changes and shadings so much admired are accidents for which the weavers are not responsible, and that consequently they are not to be credited with the beautiful effects so created. Such is the contention; but this, at all events, is certain—that the Ardebil carpet owes its power of radiating light to these changes and shadings; and if, in their production, Maksoud of Kashan showed either carelessness or Ignorance, he was probably content to feel that he shared them in common with the setting sun when he robes the sky with rainbow hues.

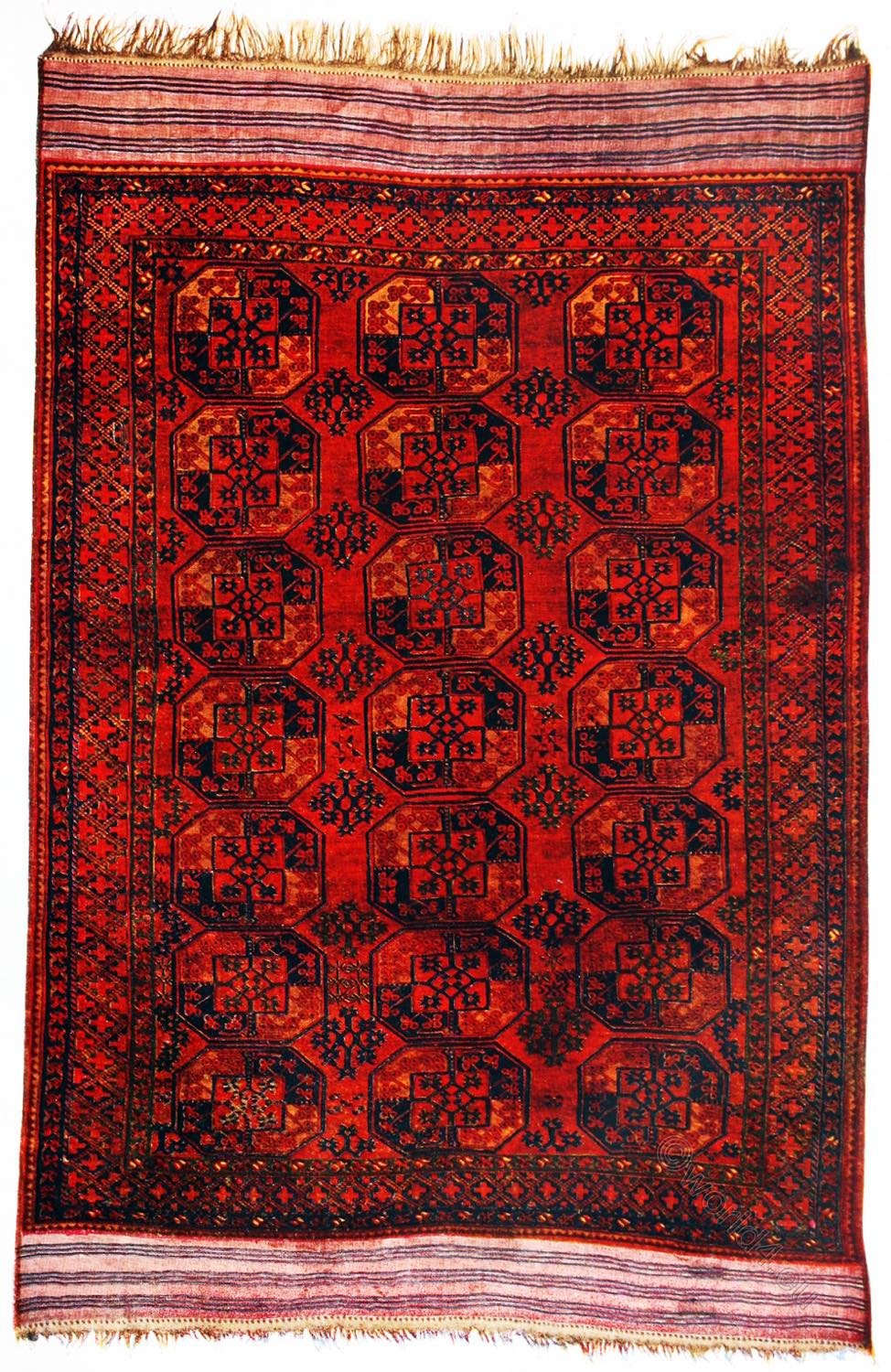

PLATE IV.

SMALL CARPET FROM THE ARDABIL MOSQUE.

XVIth CENTURY.

Dimensions : 10 ft. 7 in. x 5 ft. 10 in.

A floral tracery of soft coloring on a deep red ground forms the body of the carpet, a large number of the flowers being worked with great delicacy, as it were in relief, on a base of silk-covered wire skillfully introduced to give strength to the fabric, the whole treatment subordinate to a display of animal life, arranged in groups or pairs across the carpet.

Ten groups represent a dappled stag, pulled to the ground by a lion, and seized at the same time by a tiger. In addition to these groups, ten wild boars are represented in full flight, the drawing strikingly recalling one of the animals represented in the rock-cut sculptures of Tank-e-bostan, near Kermanshah, dating from A.D. 400. There are also ten large animals, perhaps bears, and twenty of smaller size, all drawn with great freedom.

Border: deep blue ground, relieved by a regular but conventional treatment of the “cloud” pattern in pink, and a very beautiful interlacing treble trellis of buff, light blue, and green, the latter connected, at intervals of about six inches, by flowers woven in relief, as explained above, on a flat ground of white, with a raised pile in blue and red. A narrow band of cream, relieved by a colored tracery, separates the border from the centre, and a similar band of red completes the carpet on the outside.

Date: early 16th century. Hand-tied knots to square inch, 650.

Place of origin: Kashan.

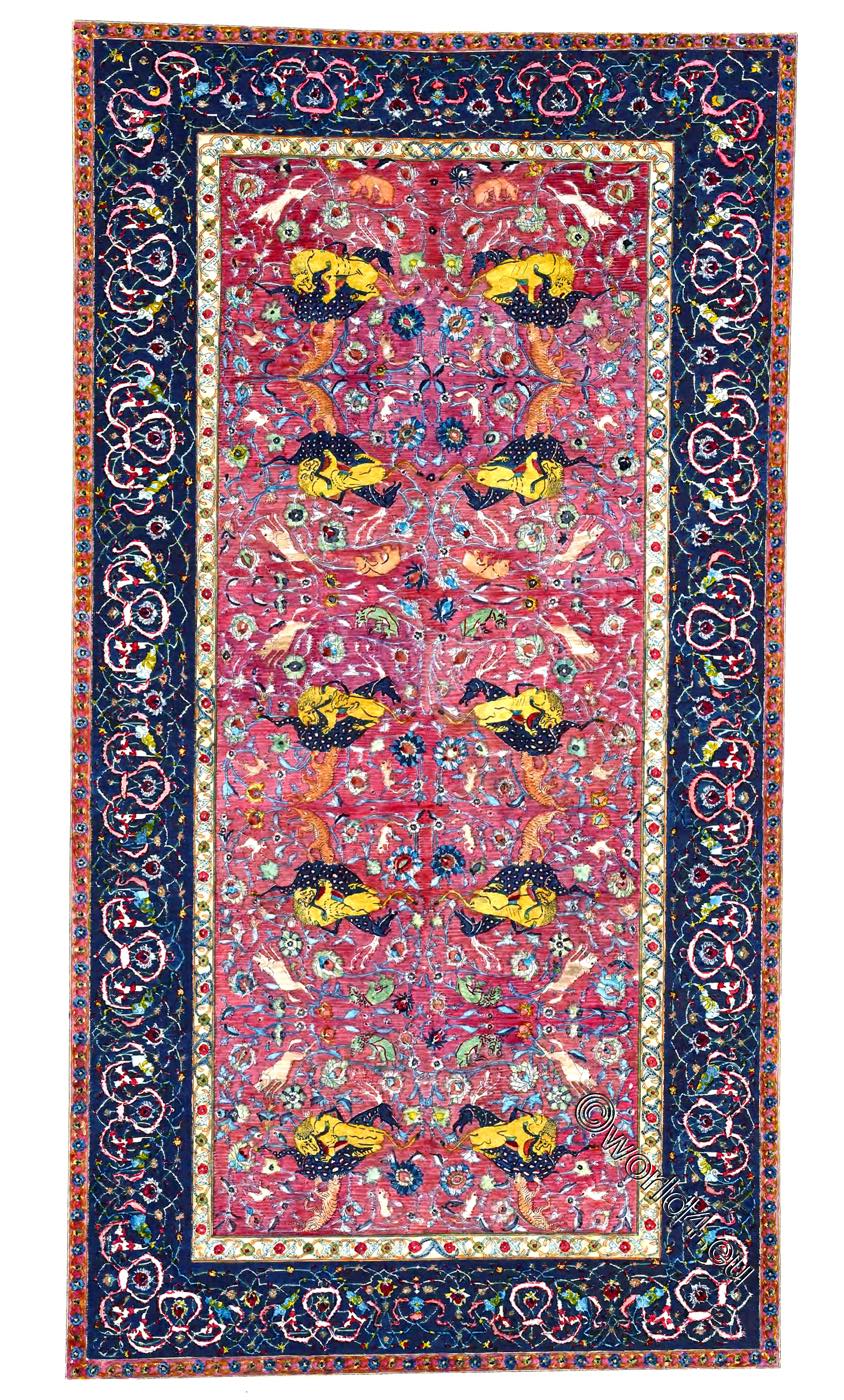

PLATE V.

SILK CARPET. XVITH CENTURY.

PRESS NOTICES

ON

THE HOLY CARPET OF THE MOSQUE AT ARDEBIL.

From “The Times,” May 26th, 1892.

Ax Extraordinary Carpet. — At the galleries of Messrs. Vincent Robinson and Co., of Wigmore Street, there will be on view in the afternoons of the next few days what may probably without any exaggeration be called the finest Persian carpet in the world. This is the Holy Carpet or the Mosque of Ardebil, in Persia; a carpet which for site, beauty, condition, and authenticated age is entirely unrivaled by any known example. To quote the description given by Mr. Edward Stubbing, the managing director of the firm, and a well-known authority on these matters, “The dimensions of the carpet are 34ft. 6in. by 17ft. 6in. The ground of the body of the fabric is of a rich blue, covered with a floral tracery of exquisite delicacy and freedom of treatment. A centre medallion of pale yellow terminates on its outeredge in sixteen minaret-shaped points, from which spring sixteen cartouches, four green, four red, and eight cream; and from two of these again are, as it were, suspended and hanging in the direction of the respective ends of the carpet, two of the sacred lamps of the mosque.”

But the most extraordinary detail of all is the pale cream cartouche placed within the border at the top end of the carpet, bearing its inwoven inscription, which is thus translated;— “I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold. My head has no protection other than this porch way. The work of the slave of this Holy Place, Maksoud of Kashan, in the year 942. “Now 942 of the Hegira is 1535 of our era; so that the carpet was actually in existence, in the Mosque of the Sacred city of the Suffavean Dynasty (Safavid dynasty), at the time when Queen Elizabeth sent Anthony Jenkinson (English diplomat 1530 – 1611) on an embassy to Shah Tahmasp I.

It need not be said that carpets thus signed and dated are extremely rare, and are historically important as forming the points de refère for the students of Oriental art. But a carpet not only dated and signed, but of such size and beauty as this, is literally a thing unheard of. In an adjoining room the firm have hung four specimens of very ancient Persian art, of much smaller dimensions, but still of great beauty and rarity, particularly one, about 7ft. by 6ft., with a deep red ground on which various forest trees are woven, with a stream running through them.

Source: The holy carpet of the mosque at Ardebil by Edward Stebbing. London: Printed by Robson & sons 1893.

Continuing