Lake Kopais, also spelled Copais or Kopaida, was a lake in the ancient landscape of Boeotia in Greece. With no surface drainage, the lake carried water only periodically and already in ancient times attempts were made to drain the lake completely. In the 19th century, these attempts were successfully resumed. The resulting plain has since been called Kopaida.

All the lake’s outlets are underground and were called chasmata (χάσματα) or baranthra (βάρανθρα) in ancient times. In modern Greek, the openings in the karstic bed beneath the lake are called katavothra (ponor, sinkhole, natural funnel-shaped depression) and are divided into different groups at the Kopaïs.

Except for three of these natural gorges at the northern edge, all other katavothren are found in the east of the lake. The ponor is a typical karst phenomenon that occurs in many regions of the earth and therefore often occurs in regions whose subsoil consists of limestone.

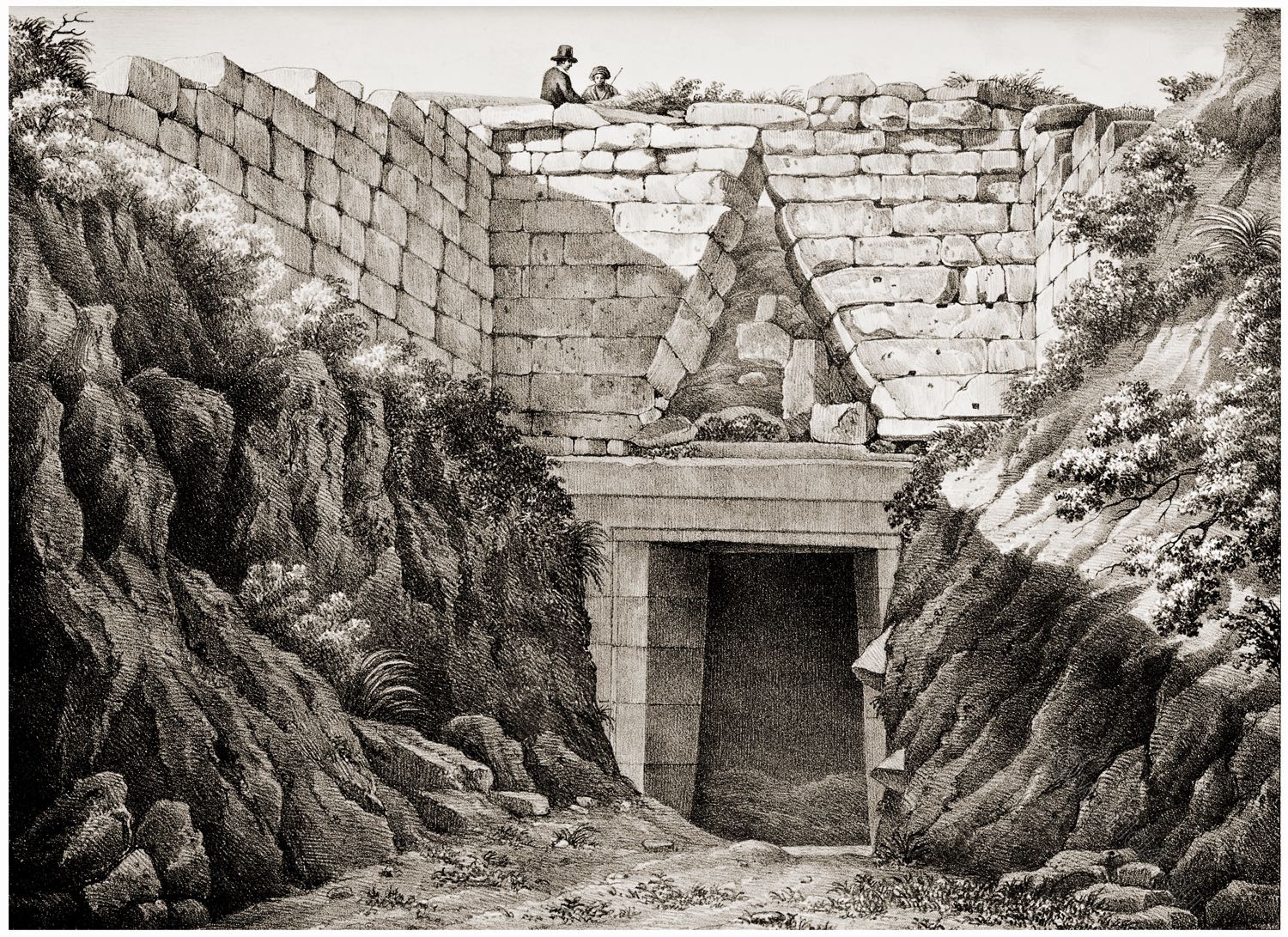

KATABATHRON OF LAKE KOPAIS

by Edward Dodwell.

LAKE Kopais, which is situated nearly in the centre of Beotia, is surrounded by lofty mountains, of which the most conspicuous are Parnassos, Helicon, Libethrion, Tilphousion, and Phoinikios, which throw out the subordinate eminences of Edylion, Akontios, Laphystios, Kyrtonon, and Ptoon.

The streams which are accumulated on these heights, descending into the intermediate plain, form the lake which was known to the ancients by the name of Kopais, or Cephissis. The two principal rivers which supply the lake are the Cephissos, and the Melas, of which the former rises at Lilaea in Phocis, and the latter a short distance from the ruins of Orchomenos.

The lake is deep only in a few places, and in summer it is nearly dry. It is, however, sometimes subject to inundations after heavy rains or when the snow is dissolved upon the surrounding mountains.

According to Pliny 1) the lake generally rose above its usual level once every ninth year. After the deluge of Deucalion nature and art appear to have combined the means of obviating the calamities occasioned by the inundation of the lake.

I allude to the subterraneous passages in mount Ptoon, through which the superfluous waters of Kopais are discharged into the lake of Hyla, and thence into the Euboean sea. They are at present denominated katabathra, and are noticed by ancient authors, particularly Strabo and Pausanias.

They pervade a calcareous rock, which is full of natural caverns and fissures. Strabo conceives that they were produced by earthquakes. He says that an inundation, which nearly demolished the city of Kopais, occasioned an aperture, through which the waters moved underground for thirty stadia, when they entered the sea near Larymna.

The Katabathron, to which the geographer alludes, is probably the same that is represented in the present plate. There are several others in the vicinity, but this is one of the largest size. It is situated between the ruins of Akraiphnion and the modern town of Talanda, at about nine miles from the former.

A large perpendicular chasm of an irregular form is seen in the rock; it is probably the work of spontaneous nature, and apparently about one hundred feet in depth. The descent is easily effected by a winding path, which is used by the shepherds when they seek in that cool recess a shelter from the sun’s scorching rays.

The bottom contains a deep pool of clear water, which oozes from the lake, and then entering a small chasm or passage in the rock finds its way to the Opuntian gulf, after a subterraneous course of about four miles.

I proceeded from hence to the side of the lake in order to inspect the mouth of the katabathron, where the water forms a gulf, and is seen flowing into the rock by three natural apertures.

1) Nat. Hist. b. 16. c. 36.

Source: Views in Greece. Drawings by Edward Dodwell. Rod Well and Martin, London, 1821.