The Hagia Sophia (Greek Αγία Σοφία Agia Sofia) is a church dedicated to the Holy Wisdom in Thessaloniki in Greece. The three-nave basilica was built in the 7th century on the foundations of a church dating back to 315; it is considered a precursor of cross-domed churches. The dome has a diameter of 10 metres and the ground plan of the church is almost square. Inside, there are mosaics from the 8th and 9th centuries.

Thessaloniki

THE CHURCH OE ST. SOPHIA.

Description by Charles Texier.

The idea of consecrating a church to the Divine Wisdom does not appear to have been realised before the reign of Justinian; but after the 6th century all the large towns of the empire emulated the example of the capital, and churches with this dedication were everywhere erected.

Several churches dedicated to St. Sophia still exist, and amongst the number the cathedral of Thessaloniki, on account of its good state of preservation and its fine construction, deserves to be classed in the first rank. In default of historical information about the date of its foundation, we may infer from its plan, and from the details of the sculpture, that the St. Sophia of Thessaloniki is contemporary with that of Constantinople, and certainly of the school of Anthemius, the celebrated architect and engineer who accompanied Justinian in all his expeditions.

When we find in Byzantine authors so many and such interesting details about the church of St. Demetrius, we are surprised to find that the cathedral of Thessaloniki is mentioned in their recitals only incidentally. Procopius, who has written six books upon the edifices constructed by Justinian, does not even mention the church of Thessaloniki, but it may be remembered that Justinian lived ten years after the book on his buildings was finished. Procopius finished his book about the year 555; Justinian died A.D. 565. 1) This explains why the erection of the castle and aqueduct of Trebizond, also the work of Justinian, 2) is not mentioned by Procopius.

This church, though it held the first rank in the town, is but little mentioned by historians. If we except the documents given by Eustathius and Comeniata, in other authors we find only a few short sentences relating to it. For instance: in the letter of the Roman pontiff, Innocent III., bishop of Neopatras, 3) in which there is mention made of the canons of Thessaloniki; it is mentioned a second time in the same letters 4) to which allusion has been made in the history of St. Demetrius; and also in the narrative of the taking of Thessaloniki by the Turks in the year 1430. 5)

During the time that the Normans were masters of the town, the priests of St. Sophia’s one day summoned the faithful to prayer by striking redoubled blows upon the semantron placed in the tower, and the Normans mistook this noise for the signal of revolt.

Tradition, whether it be that of the Greek clergy of Thessaloniki, or that of the authors who have described this church, is unanimous in attributing the erection of St. Sophia’s to Justinian; and the accordance that exists between this church and that of Constantinople goes far to confirm this opinion.

Pococke 6) remarks the resemblance of this church to that of St. Sophia at Constantinople, which was the prototype of all churches with the same dedication in the Greek empire. He makes the folio-wing observations about it

“Another mosque was the church of St. Sophia, built something on the model of St. Sophia’s at Constantinople, having a cupola adorned with beautiful mosaic-work: there arc some fine verde antique pillars in the church and portico, and in the church there is a verde antique throne or pulpit, with two or three steps up to it, the whole being of one piece of marble.”

Paul Lucas says on the same subject: 7) —

“I also visited the mosque which is still called St. Sophia; it is very beautiful and also of great extent. The bell-tower is still in existence; it is built of ashlar and brickwork, like the rest of the building.”

Eustathius in his Norman narrative 8) mentions this tower in the following passage:—

“A few days after, before the celebration of the eve of the feast, the choristers mounted to the summit of our Catholic church, to give, according to custom, the signal by striking the plank …. and when they had given the signal for the feast by striking the plank in a startling manner, soon the barbarians, &c.”

1) See Asie-mineure, p. 88. 8vo.

2) According to an ancient inscription still extant at Trebizond (today Trabzon, Turkey).

3) Letters of Innocent, XIII. 13.

4) Letter XV. 86.

5) John Anagnosta, eb. XX.

6) Description of the East, vol. III. p. 213. (Richard Pococke 1704-1765, was an English travel writer and Anglican bishop.)

7) Voyage, vol. i. p. 201. Amsterdam, 1720.

8) Ch. exxu. pp. 301—350.

Felix de Beaujour, in his Tableau du Commerce de la Grèce, 1) describes the same building in the following terms:—

“The church of St. Sophia was built after the model of that of Constantinople; it is exactly of the same proportions, but one-fourth smaller in size. Tradition affirms that it was erected in the reign of Justinian, from the designs of the architect Anthemius, the same who, some years before, bad erected St. Sophia of Constantinople. The forms of these two edifices are not characterised by that pure taste and noble simplicity which give us so much pleasure in the Athenian structures; still we cannot but admire the bold idea of a circular plan placed upon arcades, united by pendentives, a mode of construction which has served as the model for all domes since raised. It must be acknowledged that there is something imposing in the general effect in both St. Sophias, but the details are insignificant; and without the collection of columns of verde antique which dazzle the eyes of Europeans, I am certain that the beauties of St. Sophia of Constantinople would not be more admired than those of St. Sophia of Saloniki; at least, we should prefer to believe that travellers admired the two equally.”

Cousinéry in his turn gives his opinion about the cathedral of Thessalonica: 2)—

“The façade is ornamented with an octostyle portico, four columns of which are of verde antique, and four of white marble. The interior has nothing remarkable about it but the mosaic of the cupola, where are represented the twelve Apostles upon a gold-coloured ground: this mosaic becomes deteriorated day by day, and the sacristan detaches fragments of it, which he sells to Europeans.”

Leake says: 3)—

“Aghia Sophia is a mosque so called by the Turks, and which, like the celebrated temple at Constantinople, was formerly a church dedicated to the Divine Wisdom. The Greeks assert it to have been built by the architect of St. Sophia at Constantinople; its form is at least similar, being that of a Greek cross, with an octostyle portico before the door, and a dome in the centre, which is lined with mosaic, representing various objects much defaced; amongst them I can distinguish saints and palm-trees.”

When Bayezid I (1360–1403) took Thessaloniki, A.D. 1391, he converted the church of St. Demetrius into a mosque, but the Greeks remained in possession of their cathedral. Sultan Amurath, in the year 1430, allowed them the use of the principal churches; but in the year 993 of the Hegira, A.D. 1589, Ratkoub Ibrahim Pasha (1493-1536), governor of Thessaloniki, took the church of St. Sophia from the Christians and converted it into a mosque, retaining its name of Aghia Sophia, and preserving the mosaics of the dome and choir from injury.

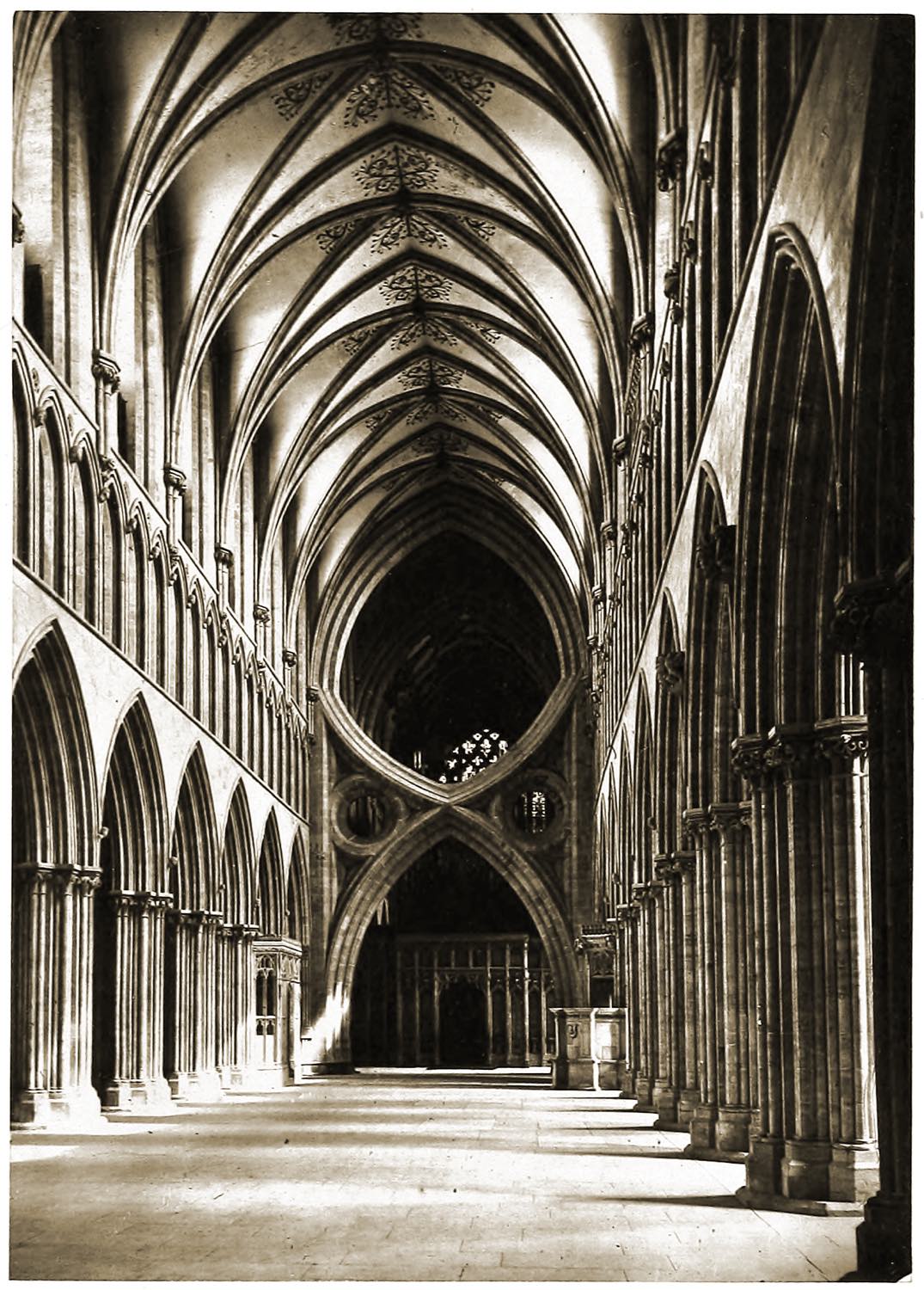

The church stands in the midst of an enclosure planted with trees; around it are Turkish schools and hospitals, which formerly were the habitations of the Greek priests. The building occupies a square of about thirty-three yards; it is built of ashlar masonry and bricks intermixed, and lined with slabs of white marble. The entrance of the church has in front of it a portico of eight columns of verde antique, supporting arches that have been entirely rebuilt by the Turks; the round arches of the Byzantines have been replaced by the pointed arches; and the capitals are Turkish in style, such as we see in modern mosques.

On entering, we come into a long transverse passage,— the narthex, which communicates with the nave by means of three doorways and by windows, through which catechumens and penitents heard the services; the gallery is lighted by windows in the portico.

The nave, which is 34 feet wide, is surmounted in the centre by a hemispherical dome of the same dimensions, supported by four pendentives, forming on the plan a Greek cross with four equal arms. (See Plates XXXV. to XXXVIII.)

To the right and left are two side aisles (aulae), separated from the nave by four columns: this is all after the plan of St. Sophia’s at Constantinople. Another passage parallel to the narthex divides it from the nave.

The chancel, the depth of which is 22 ft. 9 in., has a waggon-headed vault, and terminates in a semicircular apse lighted by three windows.

To the right and left of the apse are the two indispensable chapels mentioned as existing in St. Demetrius’s, communicating with the chancel through two side doors. These two chapels do not range with the aisle. The level of the chancel or bema is one step above that of the chapel. The iconostasis and the ombo have both been removed by the Mussulman’s.

1) Vol. I. p. 43

2) Voyage en Macêdoine, vol. i. p. 41.

3) Leake, Northern Greece, vol. III. p. 241.

A staircase situated at the left end of the narthex conducts to the gynaeconitis. This gallery runs round the nave, and forms large tribunes supported by columns: this arrangement is also to be seen in St. Sophia’s at Constantinople.

The same staircase leads into the interior of a small tower in which was placed the semantron, which was used until the 9th century. The columns on the ground-floor are of the Corinthian order, and the capitals are similar to those in the church of St. Demetrius; they are surmounted by a dosseret ornamented with a cross. (See Plate XXXIX.)

The capitals of the columns of the narthex are of the cubical form invented by the Byzantines; their faces are adorned with crowns of olives surrounded by a wreath of a character that reminds one of Greek work. The dosseret is ornamented with a cross. The bases of the columns are all more than half a diameter high.

The capitals of the upper gallery are Ionic; hut this order was generally stunted and without grace in Byzantine times. The dosseret is excessively high; it is ornamented with a simple cross. The imposts and archivolts are ornamented with very simple mouldings, composed of a cavetto and ogee. The cupola is lighted by a dozen round-arched windows. The thrust of the vault is counteracted externally by stone buttresses; it seems to have been strengthened by a stone basement.

The aisles have waggon-headed vaults outside; they have roofs covered with lead.

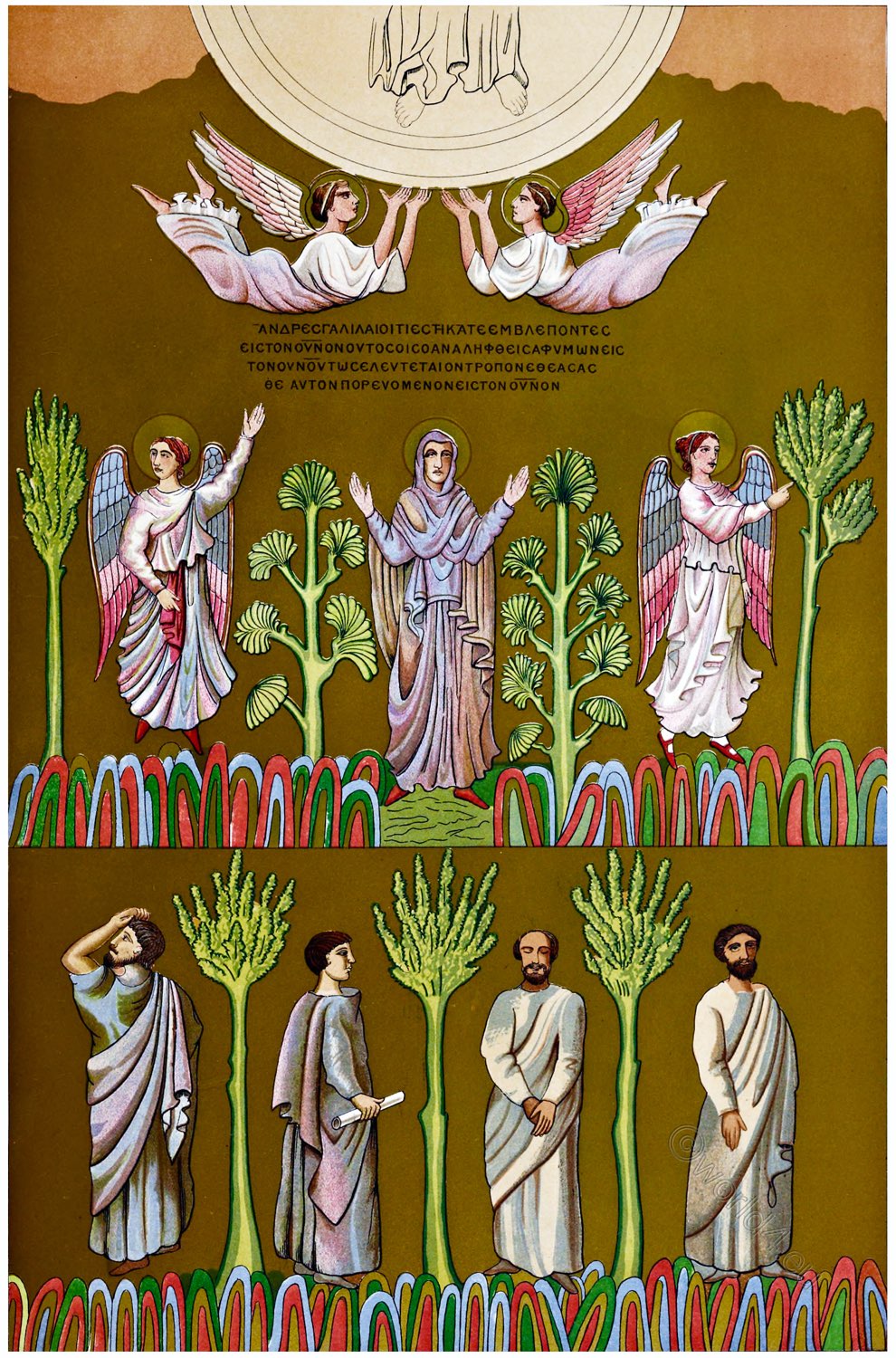

The Mosaics.

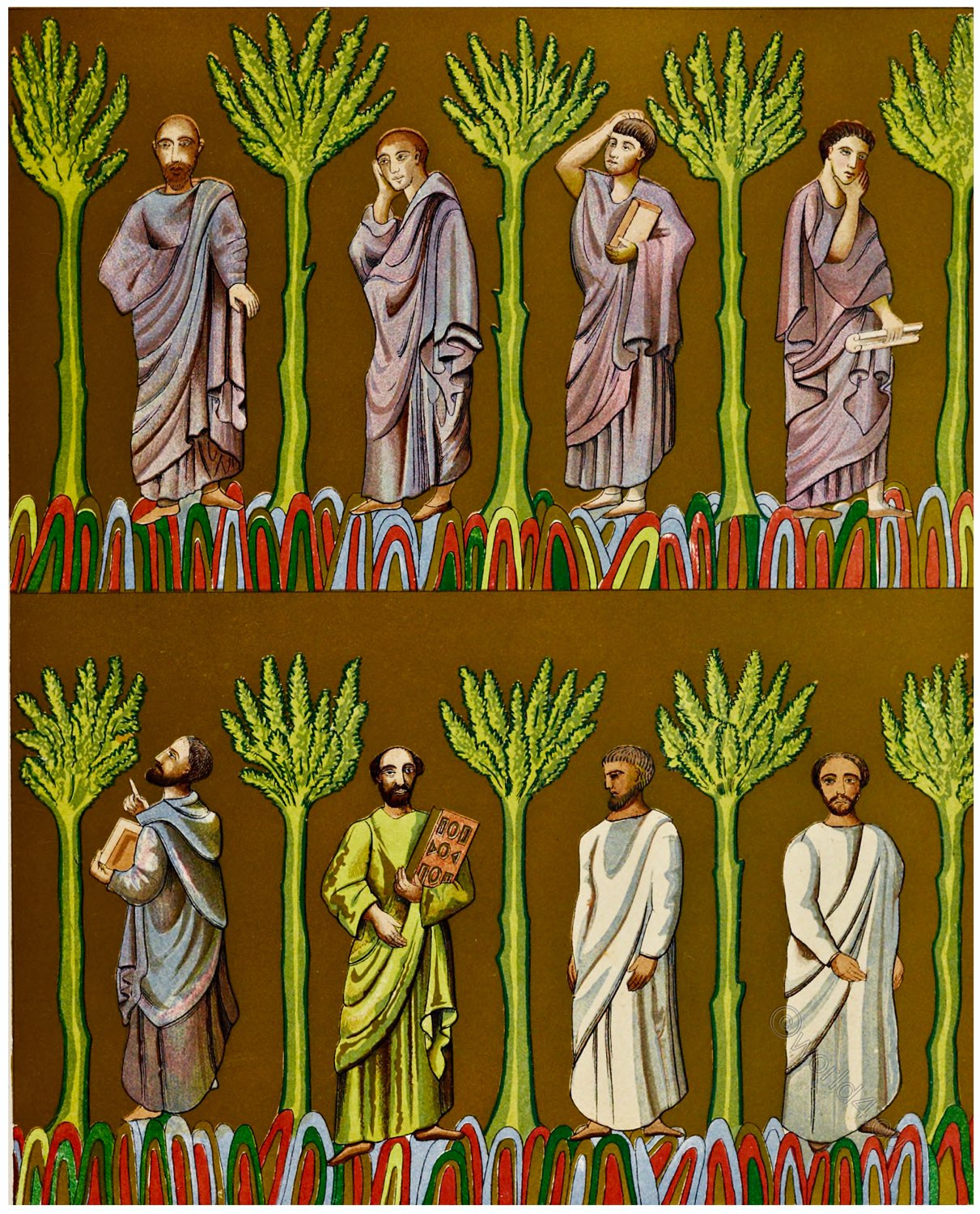

The dome is adorned with a large mosaic on a gold ground, which covers the whole surface. The subject represented is the Ascension. In the centre, on a circular medallion, is the figure of our Saviour, of which only the feet are at present visible, the rest being hid by an Arabic inscription. The circumference of the dome is occupied by the twelve Apostles and by the figure of the Virgin between two angels. The figures are all separated from one another by olive-trees: near the Virgin there are two trees of a fantastic character. (See Plates XL. XLI.)

The Virgin is clad in a purple chlamys; she is veiled, and her hands are pressed together. To the right and left of the Virgin arc two angels clad in white tunics, and having scarlet sandals; they have light hair fastened with blue ties; their hands are raised towards heaven, pointing to the risen Saviour.

Above this group are two other angels supporting the medallion on which is the figure of Christ. Between the angels and the figure of the Virgin is the following inscription on a gold ground:—

Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven? this same Jesus, which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as ye have seen him go into heaven.

All these figures have their heads ornamented with nimbi.

Round the dome are the twelve Apostles assisting at the Ascension. They are all to be distinguished by their attributes: the Evangelists hold books richly hound; the others hold rolls or diplomas in their hands. They are all represented in attitudes appropriate to the grand scene of which they are witnesses. Some support their heads with their hands; others have their eyes raised to heaven. They are all clothed in the Roman toga, of a blue colour, with dark shadows. The ground on which they stand does not resemble the earth, but is a curious collection of rocks of various colours.

Tins vast composition, which covers about six hundred square yards, the figures being more than twelve feet high, is executed in a superior manner to many of the works of the Middle Ages that we observe in the West. We see that the traditions of the Roman school of art wore not yet forgotten. The pictures of the churches of Thessaloniki, too lone neleeted ought to throw some light upon our knowledge of the Byzantine school.

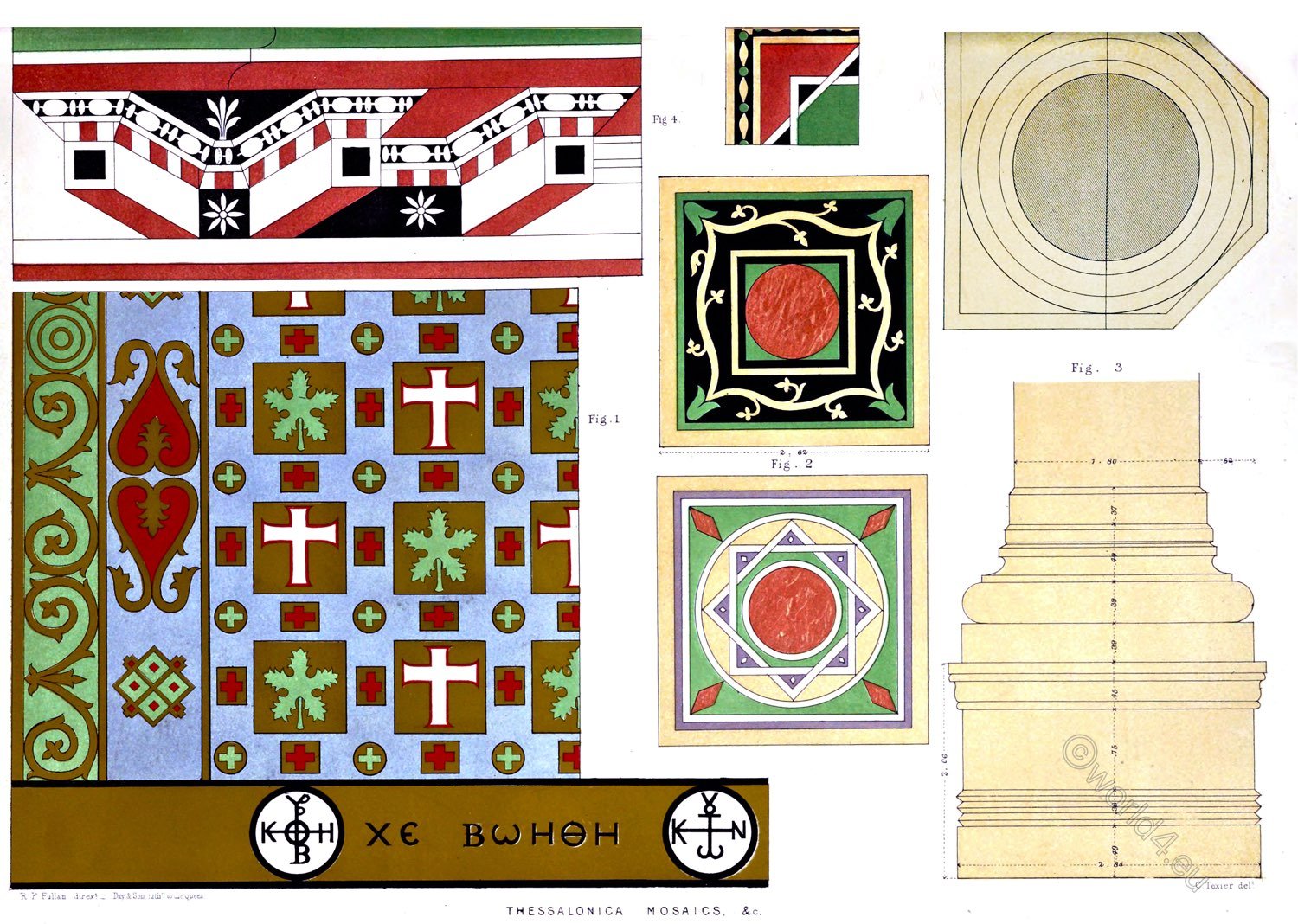

We have a few words to add about the apse. The hemispheres of the Byzantine absides are invariably adorned either with a colossal figure of Jesus Christ, or with a representation of the Virgin seated, holding in her hand the infant Jesus. The latter decorates the apse in the church of St. Sophia. The walls of the apse are ornamented by a mosaic representing a design composed of alternate squares; in one is a silver cross, in the other a vine-leaf (See Plate XXVI.).

All the mosaics are executed with a finish rarely seen in works of the same kind. We ought to render this justice to the Turkish ministers of religion at Thessaloniki, that, notwithstanding the great number of Christian figures in this edifice, it is still the object of their most assiduous attention.

In the pavement of the women’s gallery, which is almost entirely composed of Byzantine brick, we find stamps like those which we mentioned as existing in the church of St. George.

PLATES

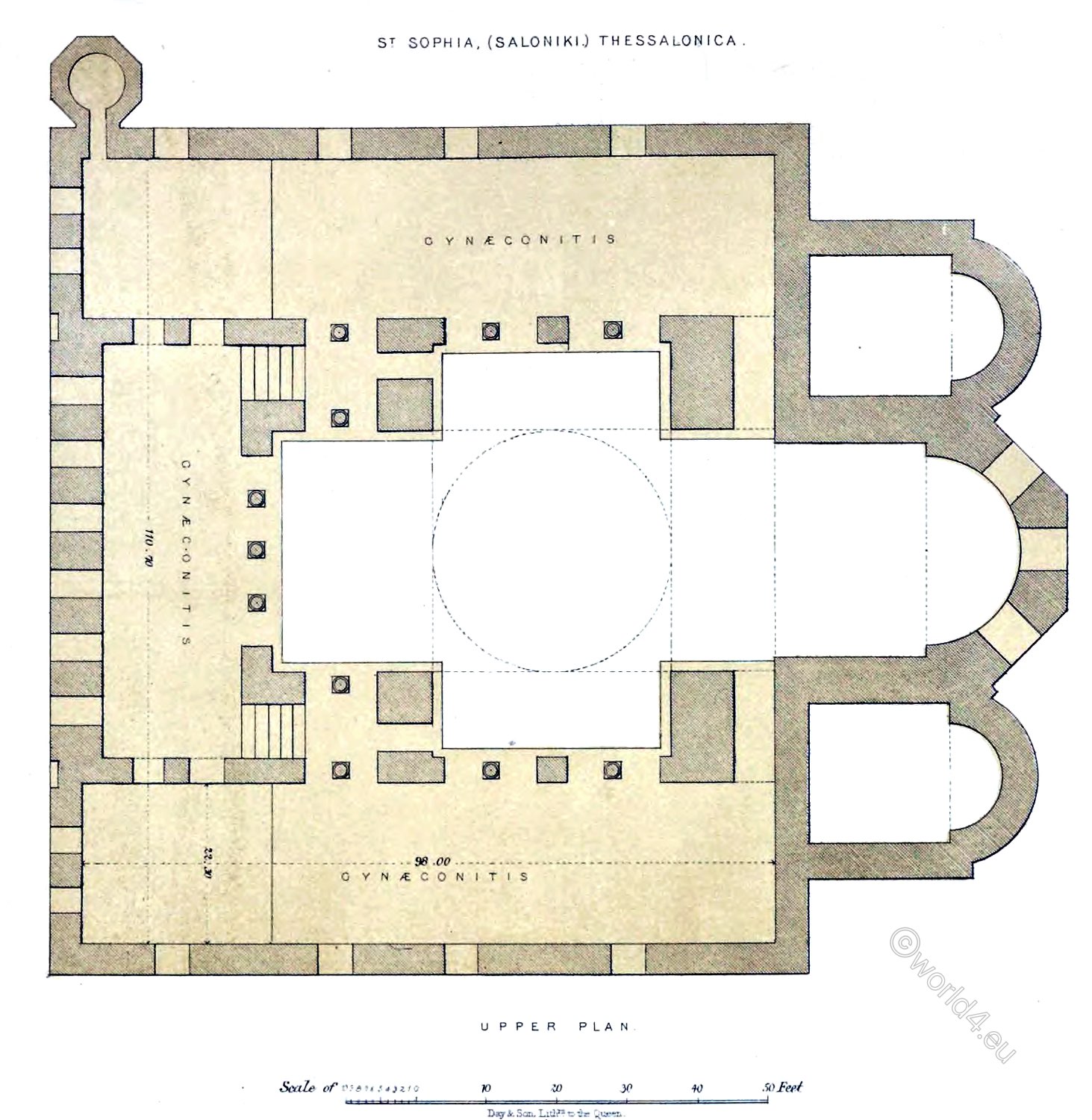

Plate XXXV.

PLAN OF THE CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA, THESSALONICA.

The porch in front of the narthex is a modern Turkish work. Probably the primitive facade was very simple in character. We may remark from this plan, that the architect had above all things studied to give that solidity to his building which is so necessary in a country subject to severe shocks of earthquakes.

There was no exonarthex here, as in the church of St. Sophia at Constantinople, although the designer of this building evidently took that building as his model.

At the end of the narthex there is a staircase leading to the turret and to the women’s gallery.

Plate XXXVI.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA, THESSALONICA — PLAN OF THE UPPER STORY.

The gallery here shown was reserved exclusively for women, and was so arranged that they could walk round the nave. The plan is the same at Constantinople.

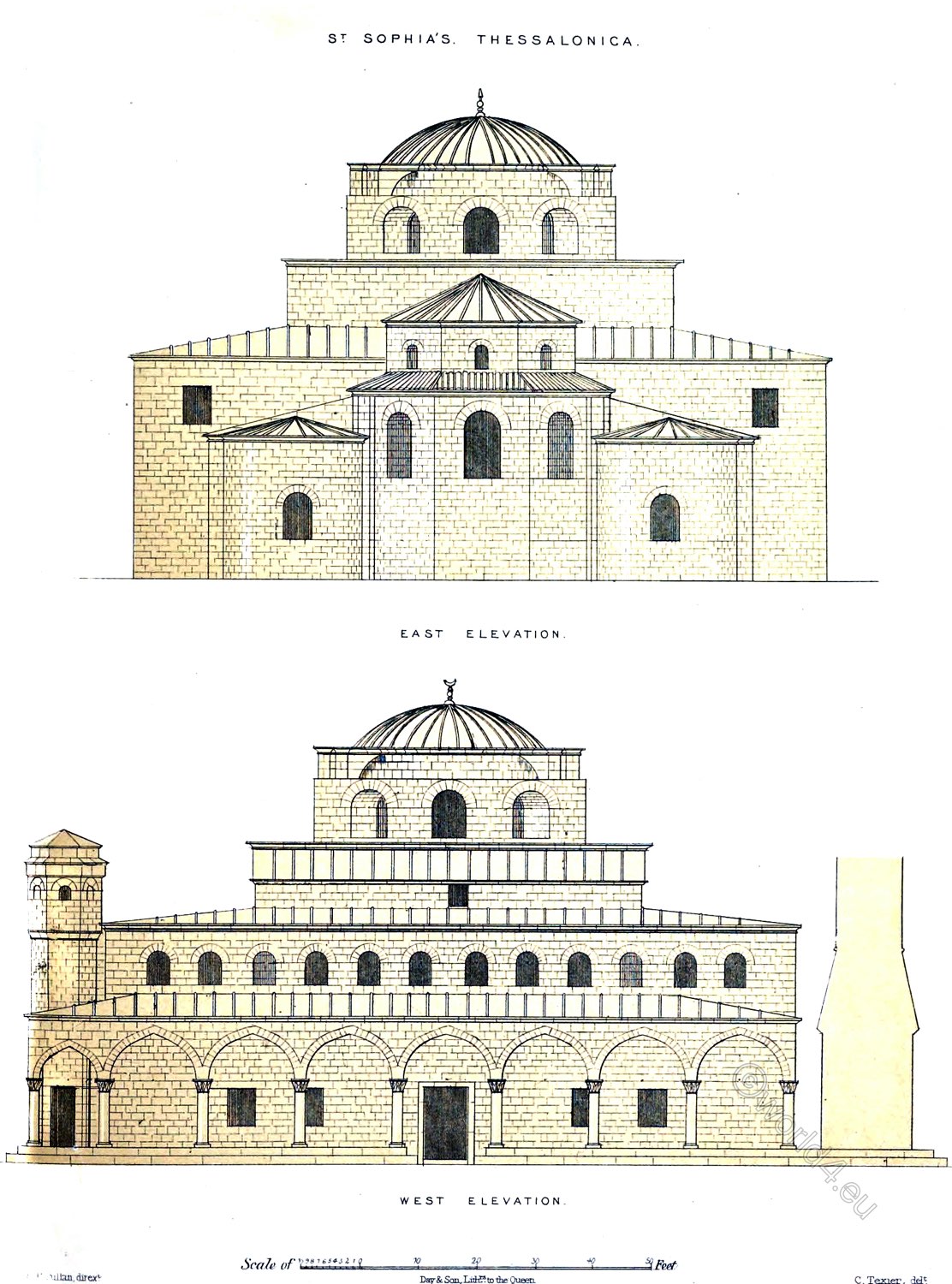

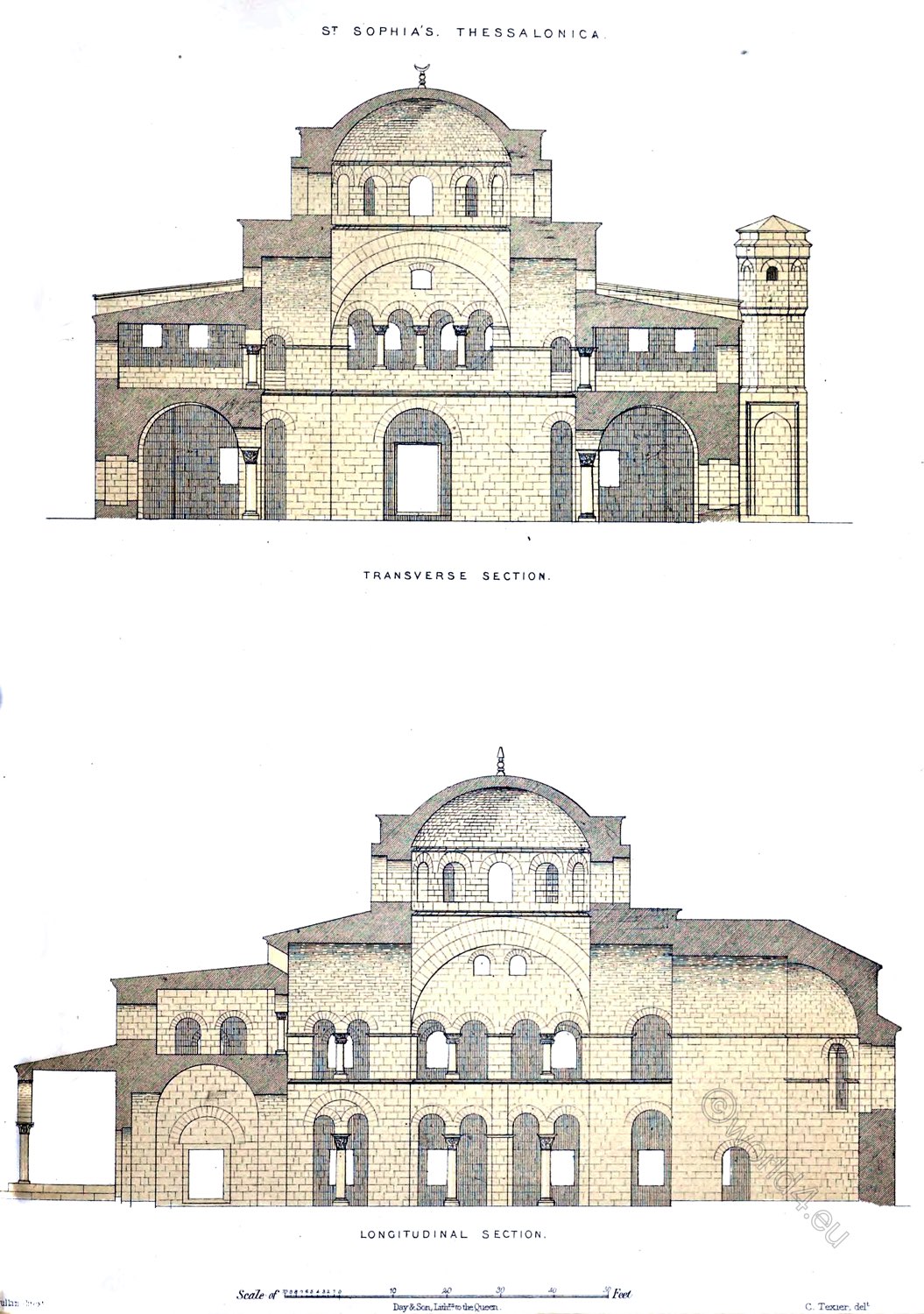

Plate XXXVII.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA — WEST ELEVATION — EAST ELEVATION.

Plate XXXVIII.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA — LONGITUDINAL SECTION — TRANSVERSE SECTION.

This edifice is an excellent example of the architecture of the time of Justinian, both in plan and elevation, and it has become the type of most of the churches subsequently built in the East. A uniform principle is found to prevail in these churches. All those on the continent of Greece have a family likeness to one another—in every case there is a central dome. As Byzantine art approached its decline, the domes were raised higher above the roof of the nave, as in the church of St. Elias at Thessalonica. (See Plates LII. to LV.)

The facade of St. Sophia’s was always very simple in character, and it resembled in that respect that of St. Sophia’s at Constantinople. The Byzantines generally reserved their ornamentation for the interior. Masonry has been employed in the place of brick for the greater part of the building. The dome rests upon a massive square basement, which we do not meet with in other cases. Upon this there are heavy buttresses, which tend to obstruct the windows and give a rather clumsy effect to the composition. These have been evidently employed to counteract the effect of earthquakes. The dome of St. Sophia’s at Constantinople has been often damaged by them, while that of Thessaloniki has not suffered at all.

The interior of the church is in accordance with the severe style of the facade. We see that the designer aimed at solidity in every part of his work. The piers which bear the cupola are well calculated to resist the thrust. The numerous columns, and, above all, the brilliant ornamentation, give a very imposing aspect to the interior.

Plate XXXIX.

CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA — CAPITALS.

We may observe in these capitals a greater departure from the classical style than in those in the church of St. Demetrius. These capitals are executed in better style than even those of St. Sophia’s at Constantinople.

The art of sculpture prevailed longer in the capital of Macedonia than in Byzantium, and we can perceive in the foliage of the cubical capital from the nave a treatment resembling that of good Greek art. The Ionic order, when used by the Byzantines was, as we have before stated, always stunted and without elegance, but it was the most difficult to execute.

Plates XL. XLI.

THE CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA — MOSAICS OF THE DOME.

The grand scene of the Ascension, which forms the subject of the decoration of the dome, is one of the best specimens of Byzantine mosaic extant. In the centre was the figure of Christ clad in a tunic: of this the feet and the skirts of the robe only are now visible. Two angels support the auriole which surrounds the Saviour. The inscription beneath contains the passage from the Acts of the Apostles relative to the Ascension.

The base of the cupola has a line of cones of various colours representing rocks, upon which stand the Apostles.

Above the centre of the apse, and thus facing those who enter at the west end, is a figure of the Virgin in the conventional dress. Her robe is purple; she has scarlet sandals on her feet; her head is encircled by a nimbus. Two trees, representing possibly pines, stand on each side. Then come two angels clad in white garments, who appear to announce the accomplishment of the great event to the world. The remainder of the pictures consists of portraits of the twelve Apostles, the most ancient without doubt that have come down to us. It is interesting to remark how exactly their conventional costume has been perpetuated in more recent times. Each figure is separated from the others by an olive-tree, indicating the place where the event happened.

These mosaics are executed with the greatest care, but we can see that the drawing has not that character of antiquity which we have remarked in the figures of the church of St. George.

The apse of St. Sophia’s is decorated with the mosaics given in Plate XXVI.

Plate XXVI.

DETAILS FROM THE CHURCHES OF ST. DEMETRIUS AND ST. SOPHIA, THESSALONICA.

The arcades of the nave have a sort of entablature above them, representing modillions *), executed in marble of three colours. (See fig.4.)

*) A modillion is an architectural element used to support a cornice, eaves or balcony. It differs from a corbel in that it is carved. There are many examples of modillions, particularly the lines of modillions on Romanesque churches.

Above the centre of each column there is a square compartment also inlaid with different coloured marbles. (See fig. 2.) On the right of the plate the bases and pedestals of the central columns of the nave are given to one-tenth full size. (See fig. 3.)

The mosaicis from the apse of the church of St. Sophia at Thessalonica. We have given an explanation of the inscriptions in the text. (See fig. 1.)

Source: Byzantine architecture; illustrated by examples of edifices erected in the East during the earliest ages of Christianity, with historical & archaeological descriptions by Charles Texier (1802-1871). London, Day & Son 1864.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.