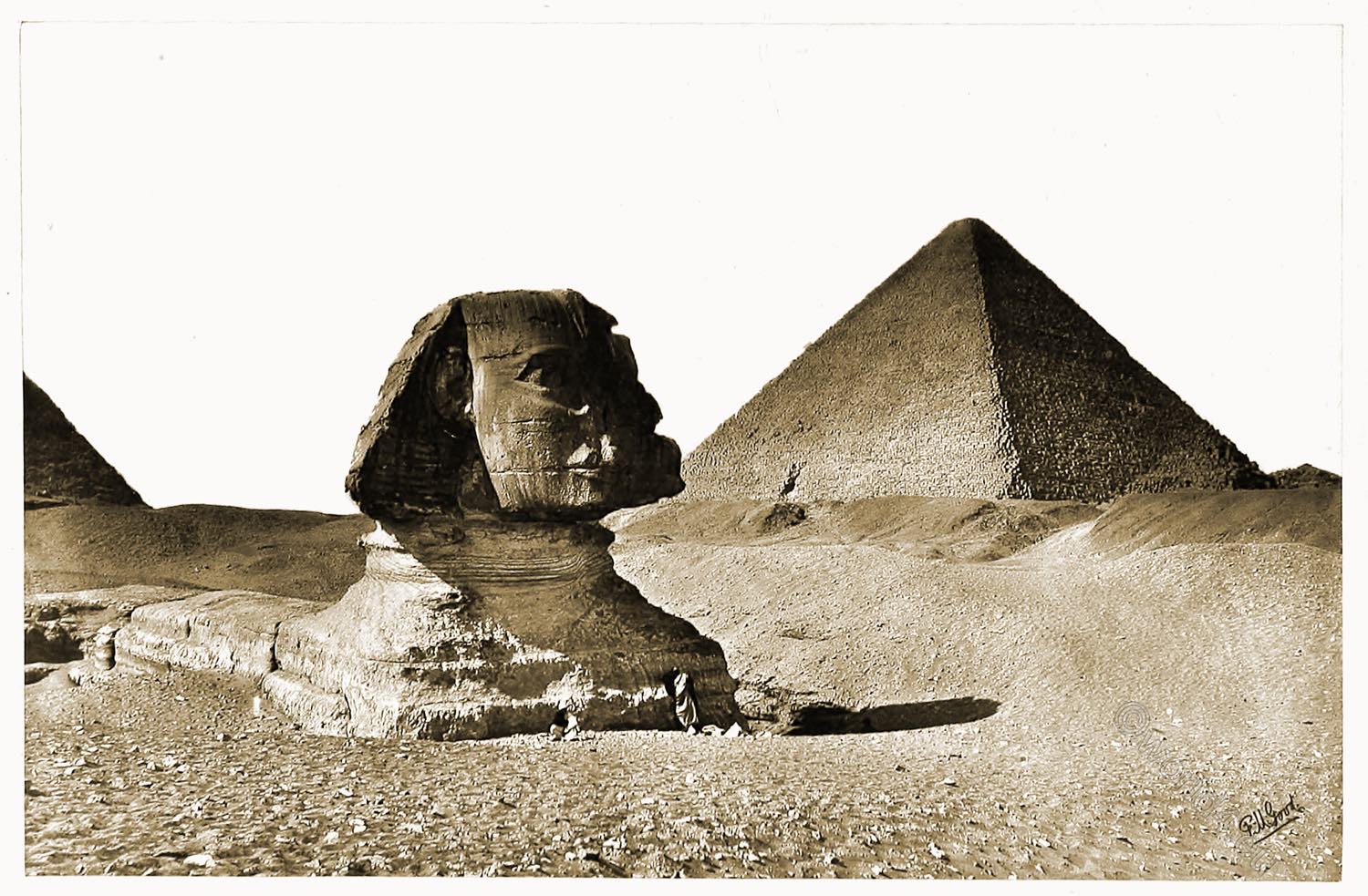

THE SPHINX AND GREAT PYRAMID

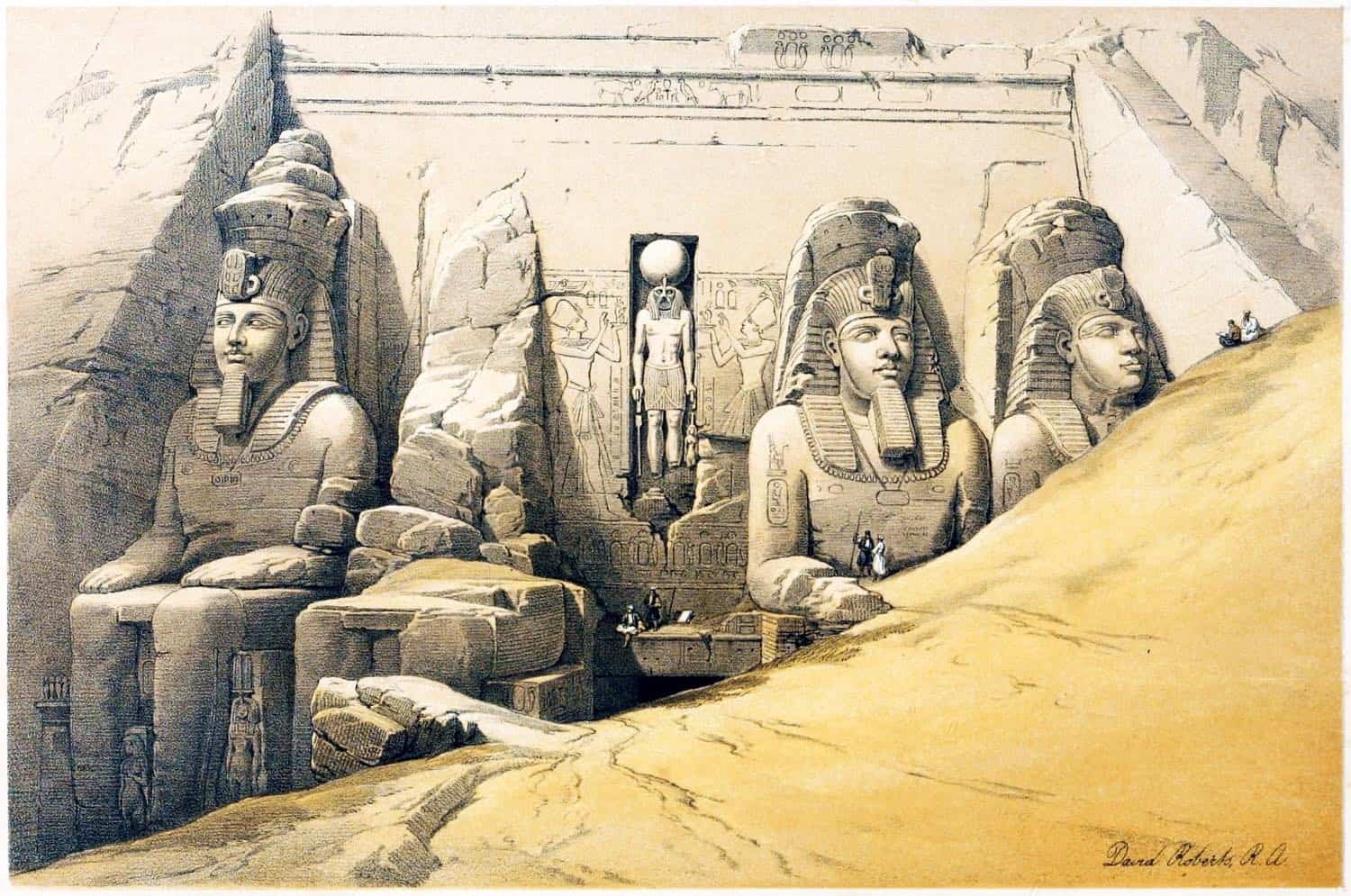

THE Pyramids of Egypt are probably the oldest monuments of human skill and industry. The great age, vast magnificence and the mystery which until lately enshrouded their origin and use, justly ranked them in former times among the seven wonders of the world. The period of their erection is the very dawn of secular history, for they were already old when Moses was rescued from the water to be the adopted son of Pharaoh’s daughter.

Various opinions have been held as to their use; but it seems to be now conclusively settled that they are tombs, built by kings who reigned between 2440 and 2080 B.C.

The first work of these kings was to prepare their graves, and they proceeded in this way: a chamber of a size to receive the intended stone coffin was cut deep in the solid rock, with a long passage to it slanting upwards and outwards. Over all this the structure was raised. Large blocks of stone, so large that this nineteenth century wonders how they could be moved, were laid tier on tier in regular progression, and the mass of building grew both in breadth and height during the monarch’s reign. At his death his sarcophagus was taken down by the long passage to its narrow resting place; the entrance was closed, and the step-like sides of the pyramid cut down smooth and cased so as to present an unbrokenly even surface. Thus the size of the pyramid was a measure of the power and resources of the king it entombed. The most remarkable of the Pyramids (of which there are seventy altogether) are at Gizeh, and of these the greatest is that of Cheops, or Kufa I.

It is said to be the result of the united labour of one hundred thousand men for half a century. Its perpendicular height is 450 feet 9 inches, and its base is 764 feet square. About 30 feet of its original height have been lost by time and violence, and, as with nearly all the rest, the fine stone casing has disappeared, and its sides are a series of rough stone steps from two to four feet in height. The summit is a platform 32 feet square.

The second pyramid, that of Kufa II., is somewhat smaller than the first, and of inferior workmanship; but it is built on a higher elevation. The third is that of Mycerinus, a kind and wise king, who was the darling of his people. Some human remains found in this pyramid, and now in the British Museum, are supposed to belong to this good king.

About a hundred yards to the east of the second pyramid is the Sphinx, the most remarkable figure of its kind. Old pictures show only a huge head rising above the sand; but the head is found to belong to a body 176 feet long and 56 feet high, cut out of the solid rock, with masonry added here and there to complete the form. Of the precise uses of this human-headed quadruped very little is known more than that it was a religious emblem; it belongs to the same age as the Pyramids.

There they stand, strange monuments of a race long passed away! Built in the infancy of science, they now overlook the highest results of human invention. The desert at their feet is crossed by the railroad and the telegraph, and the waters of old Nile are broken by the paddle-stroke of the steamboat. Our picture is a proof that the majesty of their hoary state has been invaded by the photographer’s camera-the wonder-working chamber of the youngest but most marvelous of the sciences. What greater wonders will they see ere they crumble quite away?

Descriptive Article by G. Shrewsbury. Photographed by Good.

Source: Treasure spots of the world: a selection of the chief beauties and wonders of nature and art by Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834-1885); Francis Clement Naish. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, Paternoster Row, 1875.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.