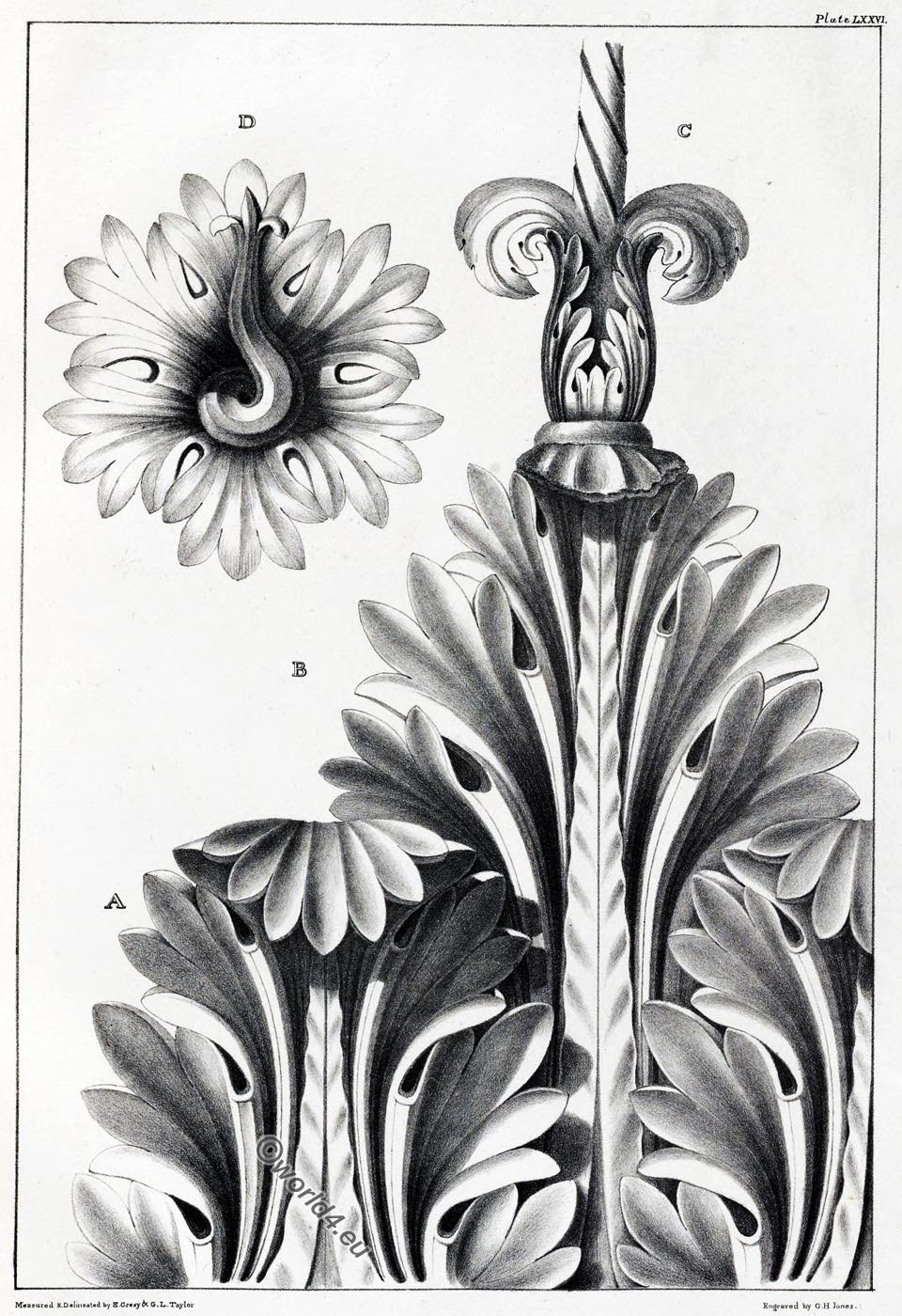

ROMAN ORNAMENT.

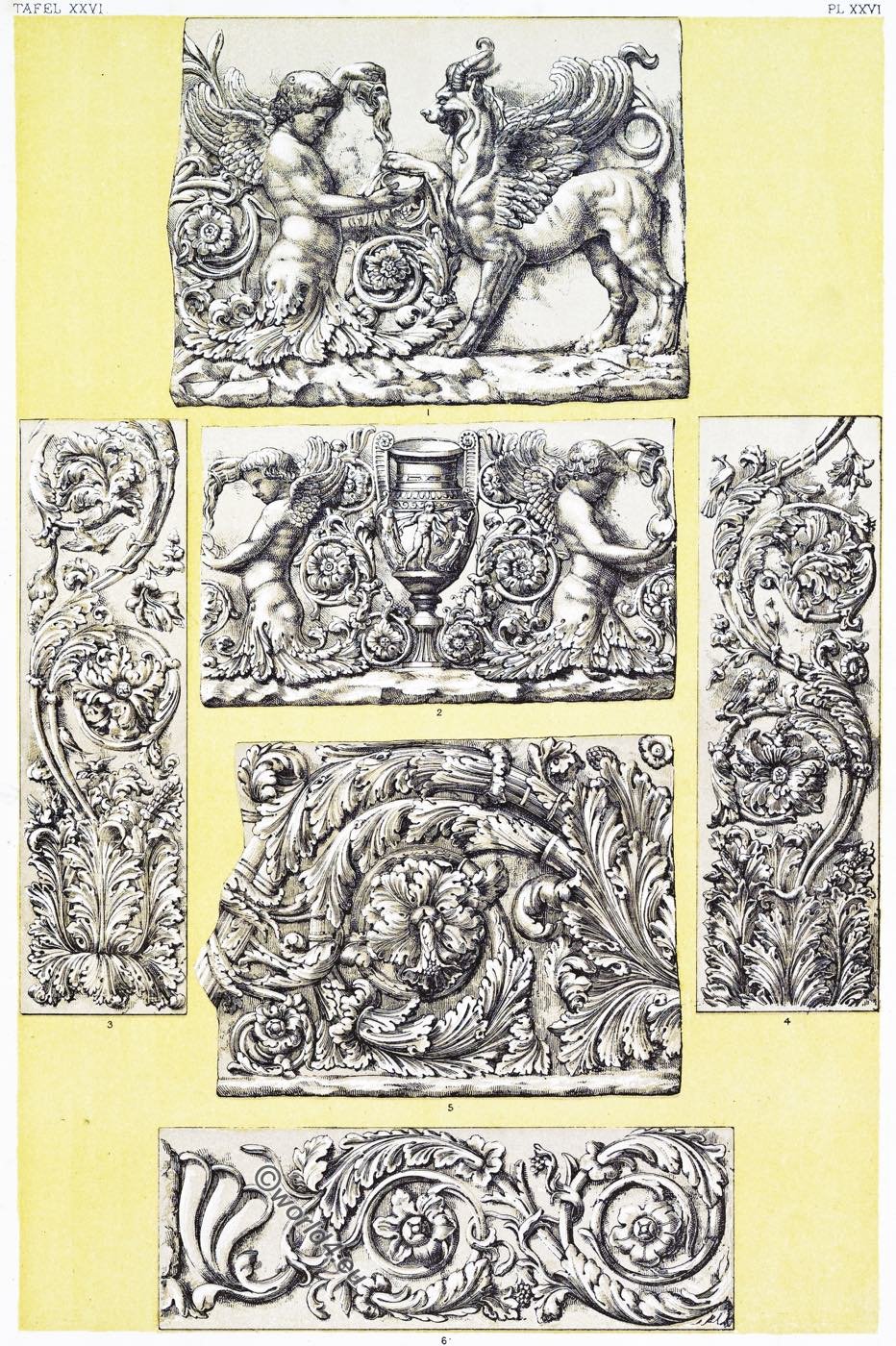

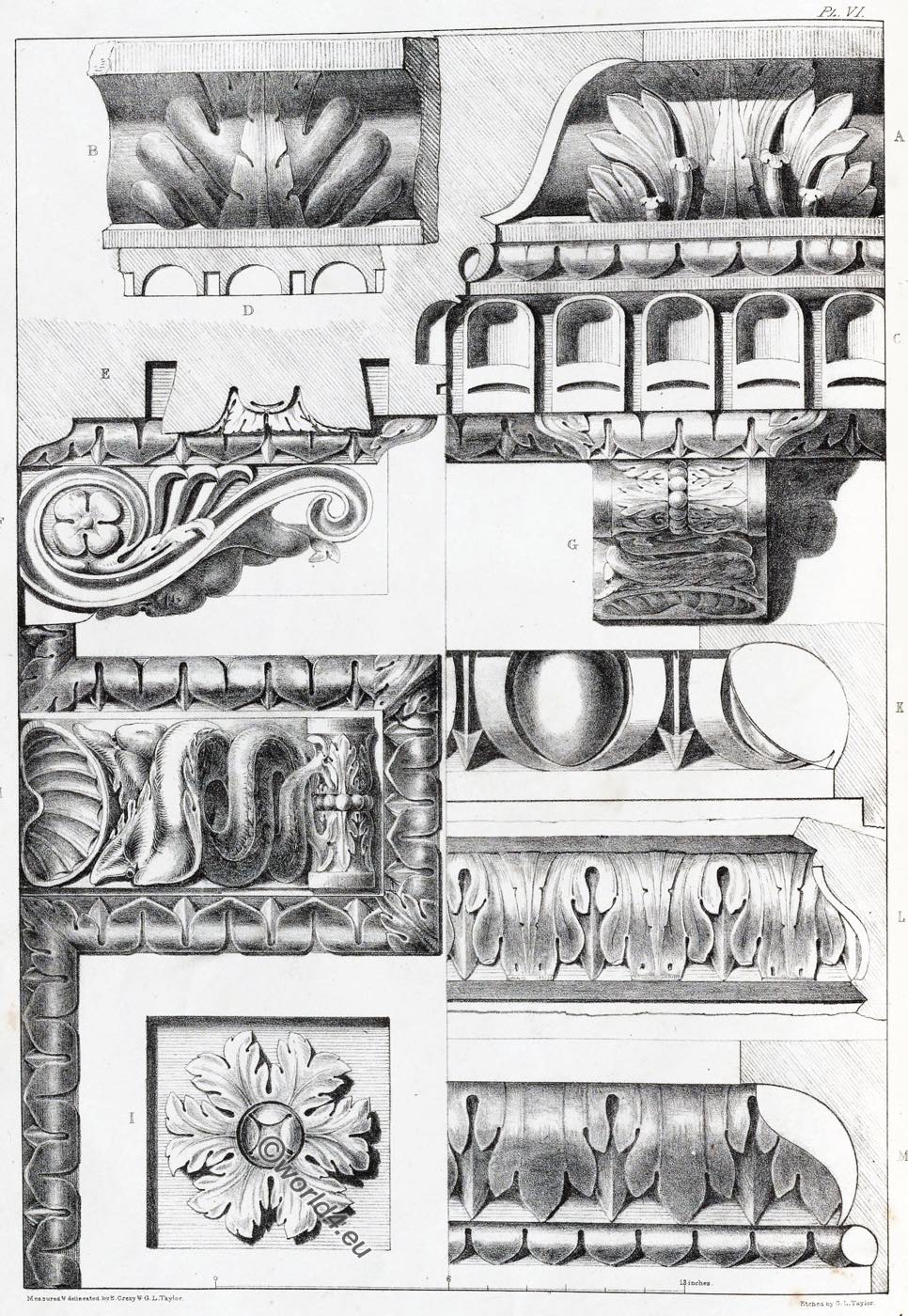

PLATE XXVI.

1, 2. Fragments from the Forum of Trajan, Rome.

3. Pilasters from the Villa Medici, Rome.

4. Pilaster from the Villa Medici, Rome.

5, 6. Fragments from the Villa Medici, Rome.

Nos. 1-5 are from Casts in the Crystal Palace;

No. 6 from a Cast at South Kensington Museum. *)

*) Examples of Ornamental Sculpture in Architecture, by Lewis Vulliamy, Architect. London. Museo Bresciano, illustrato. Brescia, 1838.

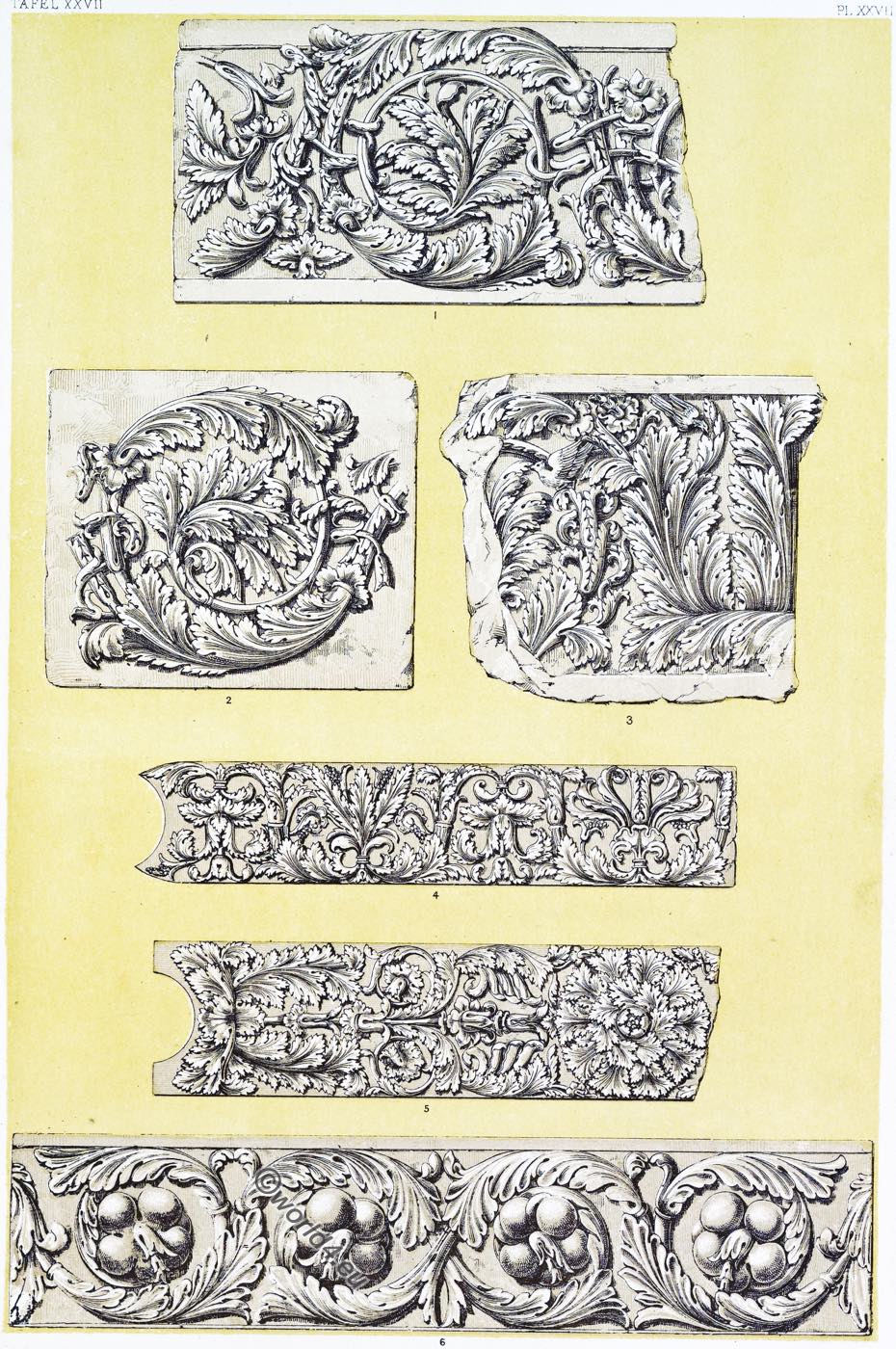

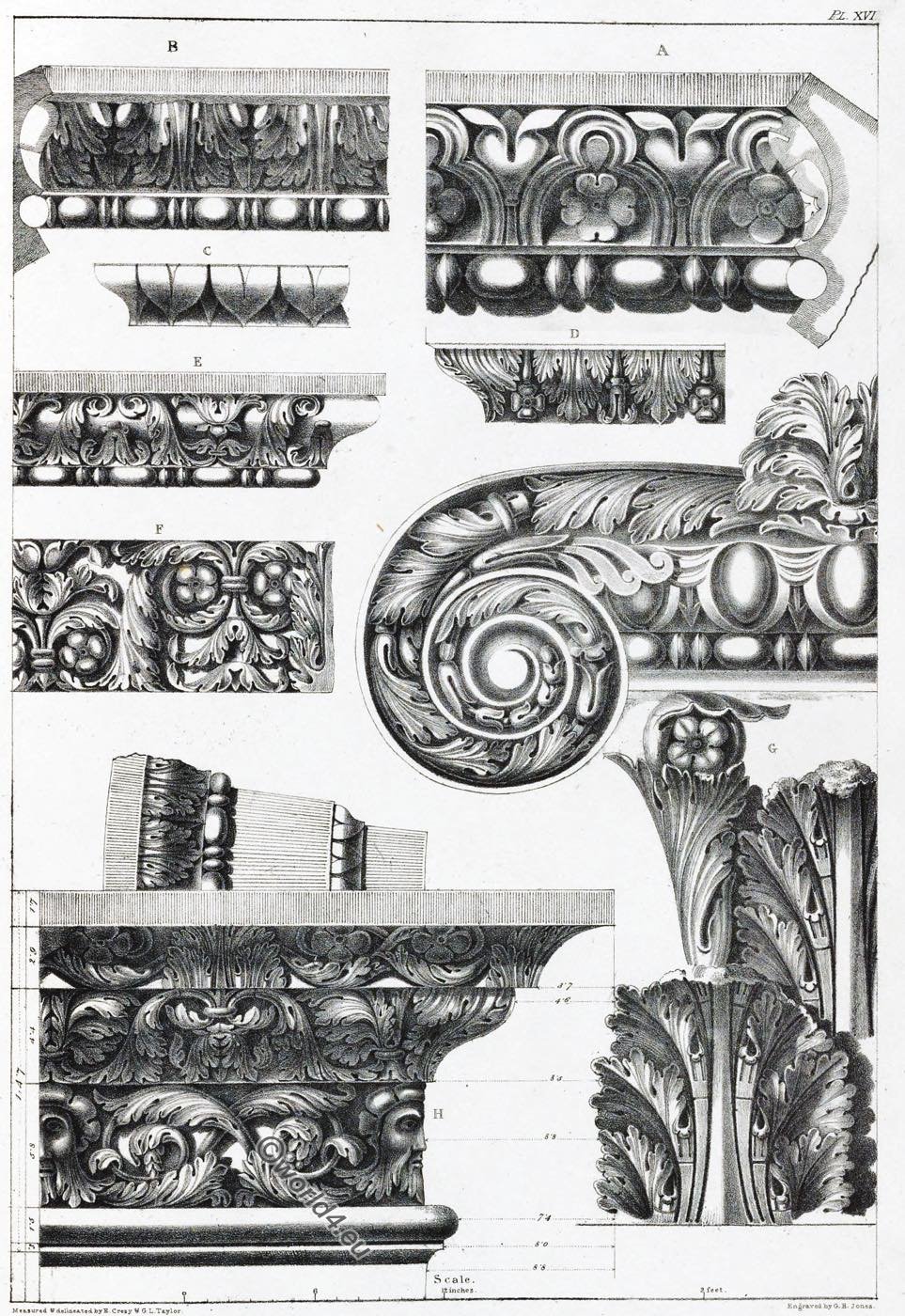

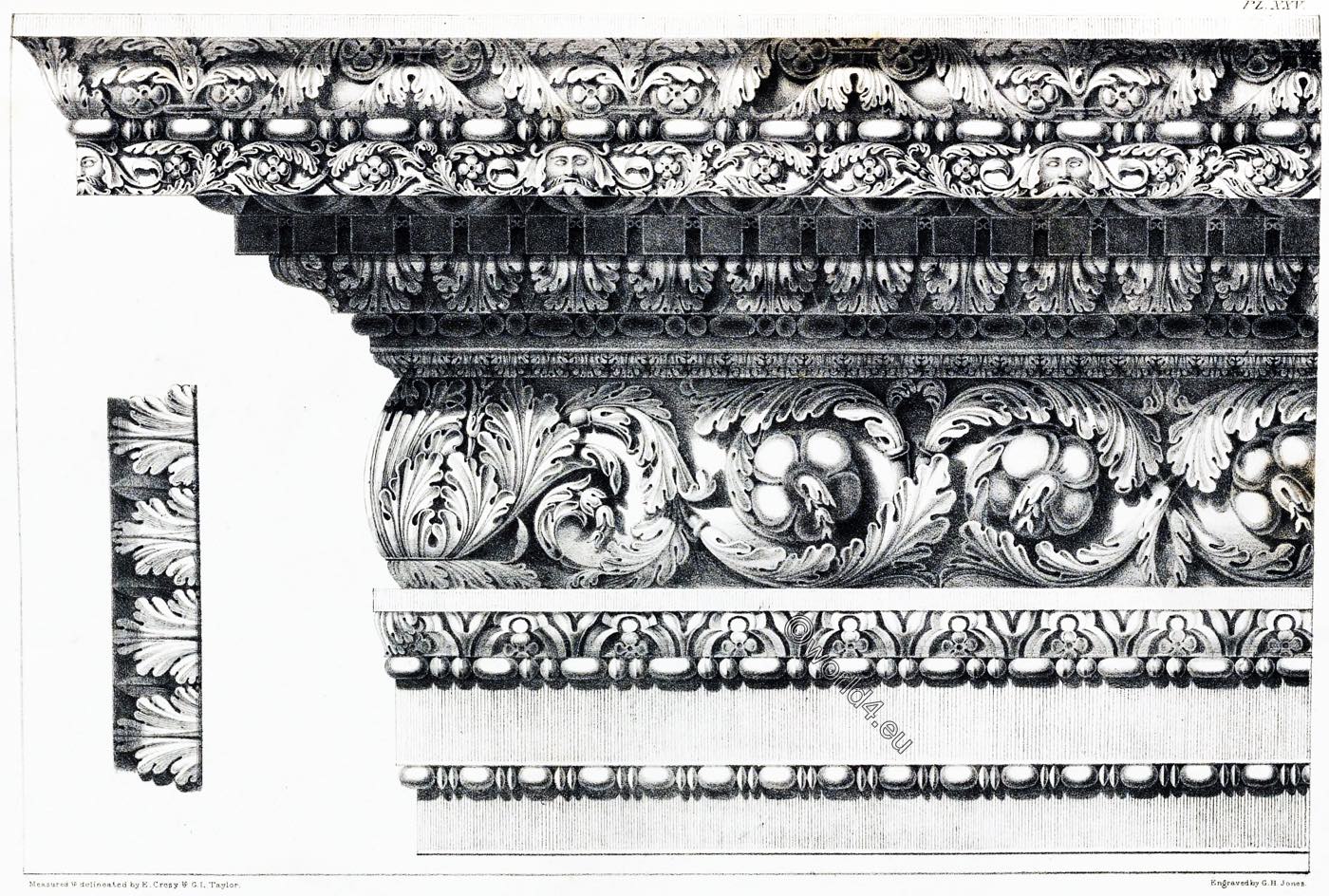

PLATE XXVII.

- 1 – 3. Fragments of the Frieze of the Roman Temple at Brescia.

- 4. Fragment of the Soffits of the Architraves of the Roman Temple at Brescia.

- 5. Fragment of the Soffits of the Architraves of the Roman Temple at Brescia.

- 6. From the Frieze of the Arch of the Goldsmiths, Rome.

- Nos. 1-4 from the Museo Bresciano; No. 5 from Taylor and Chest’s Rome.

The real greatness of the Romans is rather to be seen in their palaces, baths, theatres, aqueducts, and other works of public utility, than in their temple architecture, which being the expression of a religion borrowed from the Greeks, and in which probably they had little faith, exhibits a corresponding want of earnestness and art-worship.

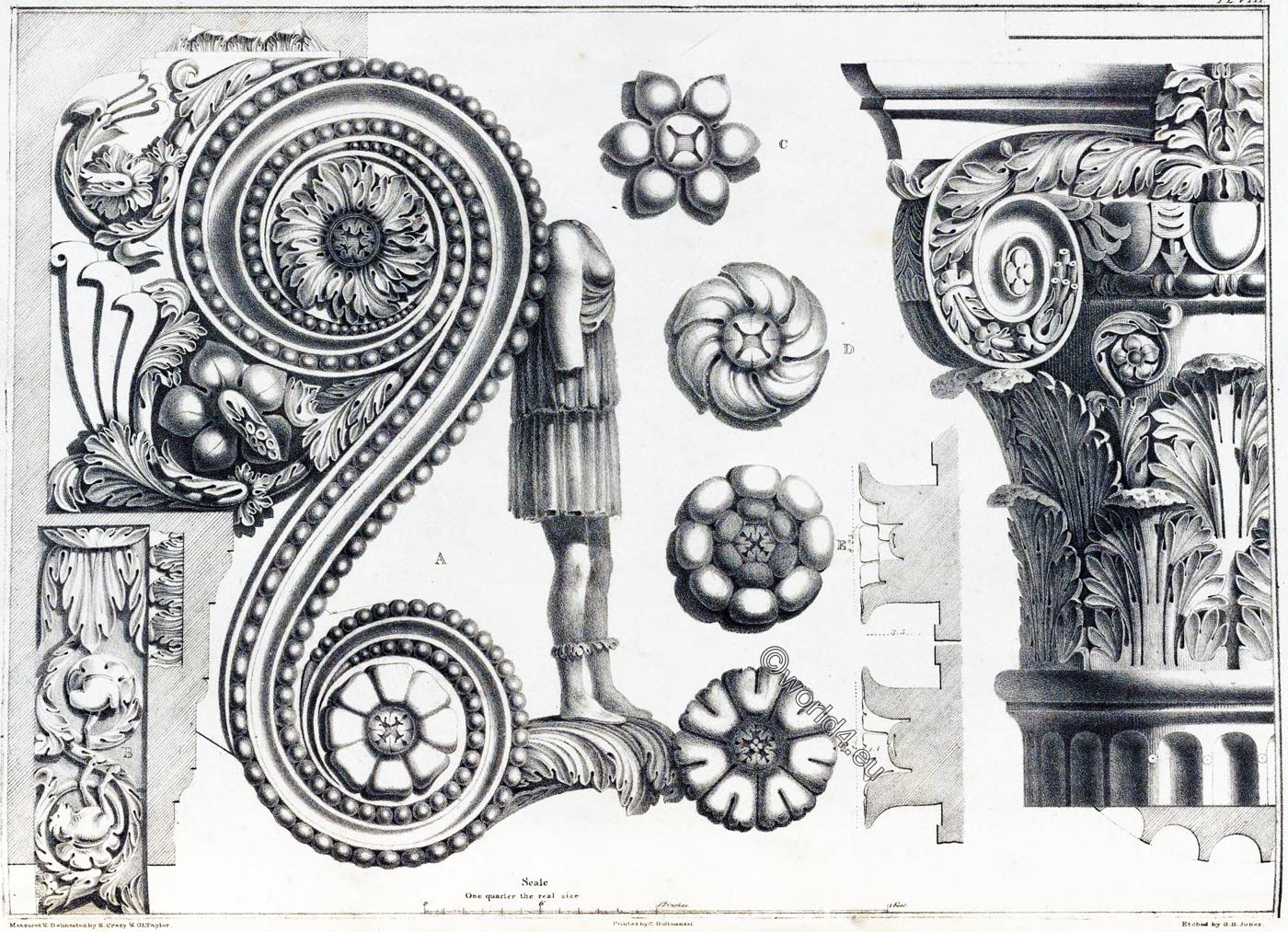

In the Greek temple it is everywhere apparent that the struggle was to arrive at a perfection worthy of the gods. In the Roman temple the aim was self-glorification. From the base of the column to the apex of the pediment every part is overloaded with ornament, tending rather to dazzle by quantity than to excite admiration by the quality of the work. The Greek temples when painted were as ornamented as those of the Romans, but with a very different result. The ornament was so arranged that it threw a coloured bloom over the whole structure, and in no way disturbed the exquisitely designed surfaces which received it.

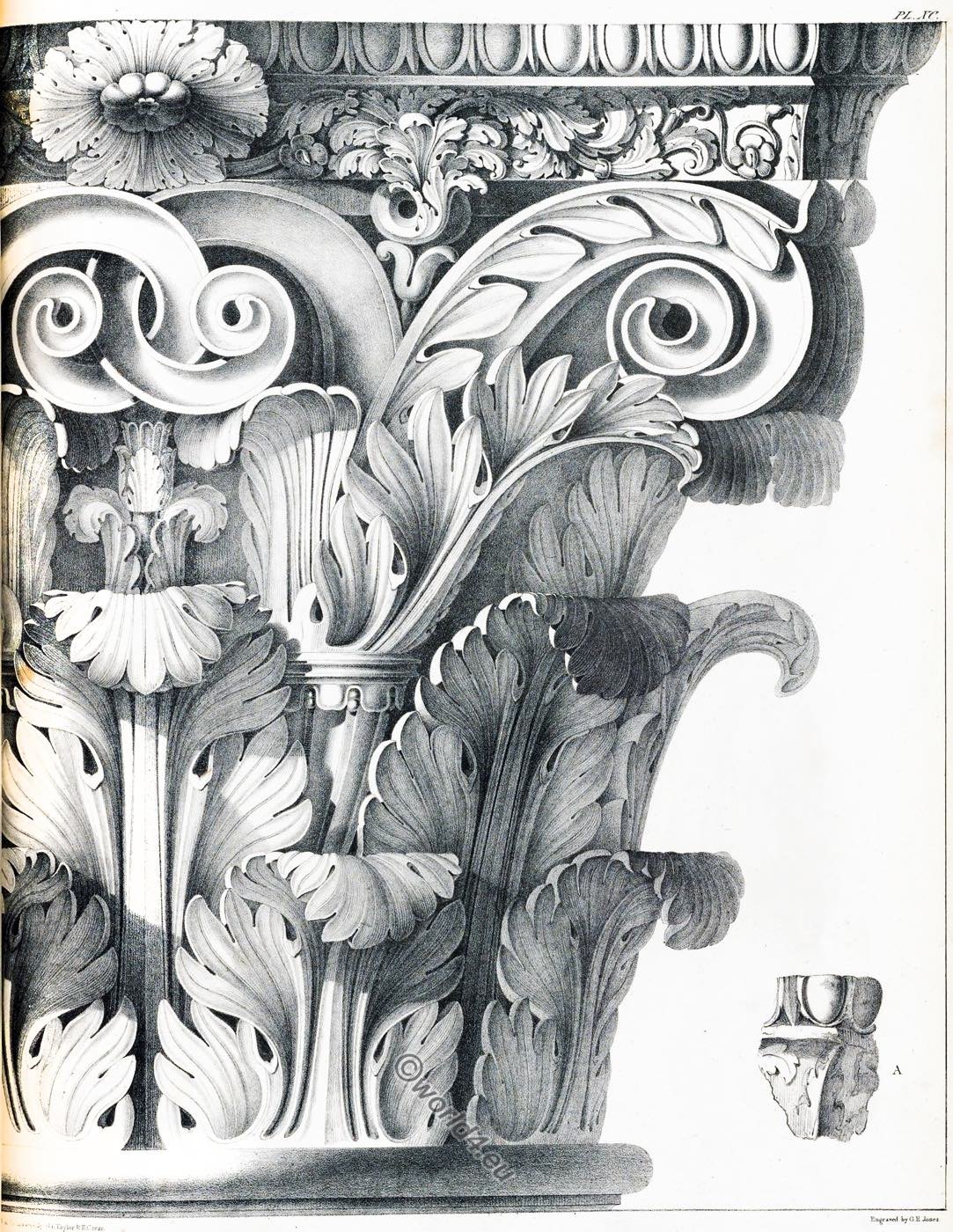

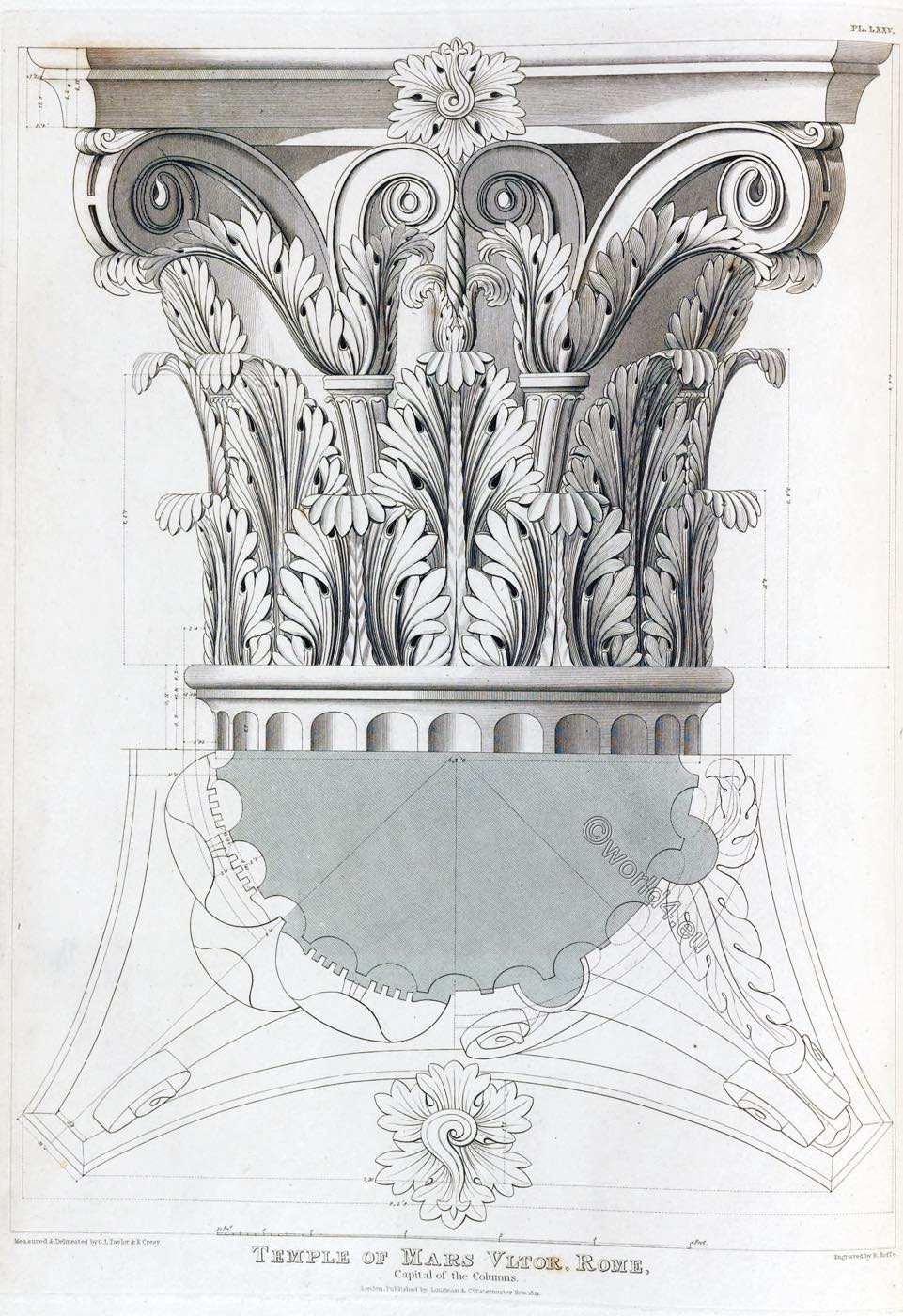

The Romans ceased to value the general proportions of the structure and the contours of the moulded surfaces, which were entirely destroyed by the elaborate surface-modeling of the ornaments carved on them; and these ornaments do not grow naturally from the surface, but are applied on it. The acanthus leaves under the modillions, and those round the bell of the Corinthian capitals, are placed one before the other most inartistically. They are not even bound together by the necking at the top of the shaft, but rest upon it. Unlike in this the Egyptian capital, where the stems of the flowers round the bell are continued through the necking, and at the same time represent a beauty and express a truth.

The fatal facilities which the Roman system of decoration gives for manufacturing ornament, by applying acanthus leaves to any form and in any direction, is the chief cause of the invasion of this ornament into most modern works. It requires so little thought, and is so completely a manufacture, that it has encouraged architects in an indolent neglect of one of their especial provinces, and the interior decorations of buildings have fallen into hands most unfitted to supply their place.

In the use of the acanthus leaf the Romans showed but little art. They received it from the Greeks beautifully conventionalized; they went much nearer to the general outline, but exaggerated the surface-decoration. The Greeks confined themselves to expressing the principle of the foliation of the leaf, and bestowed all their care in the delicate undulations of its surface.

The ornament engraved at the head of the chapter is typical of all Roman ornament, which consists universally of a scroll growing out of another scroll, encircling a flower or group of leaves. This example, however, is constructed on Greek principles, but is wanting in Greek refinement. In Greek ornament the scrolls grow out of each other in the same way, but they are much more delicate at the point of junction. The ‘ acanthus leaf is also seen, as it were, in side elevation. The purely Roman method of using the acanthus leaf is seen in the Corinthian capitals, and in the examples on Plates XXVI. and XXVII. The leaves are flattened out, and they lay one over the other, as in the cut.

The various capitals which we have engraved from Taylor and Cresy’s work have been placed in juxtaposition, to show how little variety the Romans were able to produce in following out this application of the acanthus. The only difference which exists is in the proportion of the general form of the mass the decline in this proportion from that of Jupiter Stator may be seen readily. How different from the immense variety of Egyptian capitals which arose from the modification of the general plan of the capital, even the introduction of the Ionic volute in the Composite order fails to add a beauty, but rather increases the deformity.

The pilasters from the Villa Medici, Nos. 3 and 4, Plate XXVI., and the fragment, No. 5, are as perfect specimens of Roman ornament as could be found. As specimens of modeling and drawing they have strong claims to be admired, but as ornamental accessories to the architectural features of a building they most certainly, from their excessive relief and elaborate surface treatment, are deficient in the first principle, viz. adaptation to the purpose they have to fill.

Arch of Titus, Rome 81 AD consecrated by Domitian. Total height 20 metres, attic 4.50 metres high, passage 5.34 metres wide. Pentelic marble. The wings restored in 1821.

The amount of design that can be obtained by working out this principle of leaf within leaf and leaf over leaf is very limited; and it was not till this principle of one leaf growing out of another in a continuous line was abandoned for the adoption of a continuous stem throwing off ornaments on either side, that pure conventional ornament received any development.

The earliest examples of the change are found in St. Sophia at Constantinople; and we introduce here an example from St. Denis, where, although the swelling at the stem and the turned-back leaf at the junction of stem and stem have entirely disappeared, the continuous stem is not yet fully developed, as it appears in the narrow border top and bottom. This principle became very common in the illuminated MSS. of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, and is the foundation of Early English foliage.

Victory Arch of Constantine (Arco di Costantino), Rome 312 A.D. Behind it the Colosseum. Central passage 11.40 m high, 6.60 m wide, side arches 3.40 m wide. Column shafts of Numidian marble. The Arch of Constantine is a three-arched triumphal arch in Rome. It was built in honour of the emperor Constantine the Great in memory of his victory at the Milvian Bridge (in 312) over his adversary Maxentius.

The fragments on Plate XXVII., from the Museo Bresciano, are more elegant than those from the Villa Medici; the leaves are more sharply accentuated and more conventionally treated. The frieze from the Arch of the Goldsmiths is, on the contrary, defective from the opposite cause.

We have not thought it necessary to give in this series any of the painted decorations of the Romans, of which remains exist in the Roman baths. We had no reliable materials at command; and, further, they are so similar to those at Pompeii, and show rather what to avoid than what to follow, that we have thought it sufficient to introduce the two subjects from the Forum of Trajan, in which figures terminating in scrolls may be said to be the foundation of that prominent feature in their painted decorations.

Source:

- The grammar of ornament by Owen Jones, John Burley, John Obadiah Westwood, Sir Matthew Digby. Publisher London: Bernard Quaritch, 15 Piccadilly, 1868.

- The architectural antiquities of Rome by George Ledwell Taylor and Edward Cresy. Publisher London: Published by G. L. Taylor, 1821. Printer: James Moyes.

- The Architecture of Antiquity by Ferdinand Noack (1865-1931). Berlin: Fischer & Francke, 1910.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.