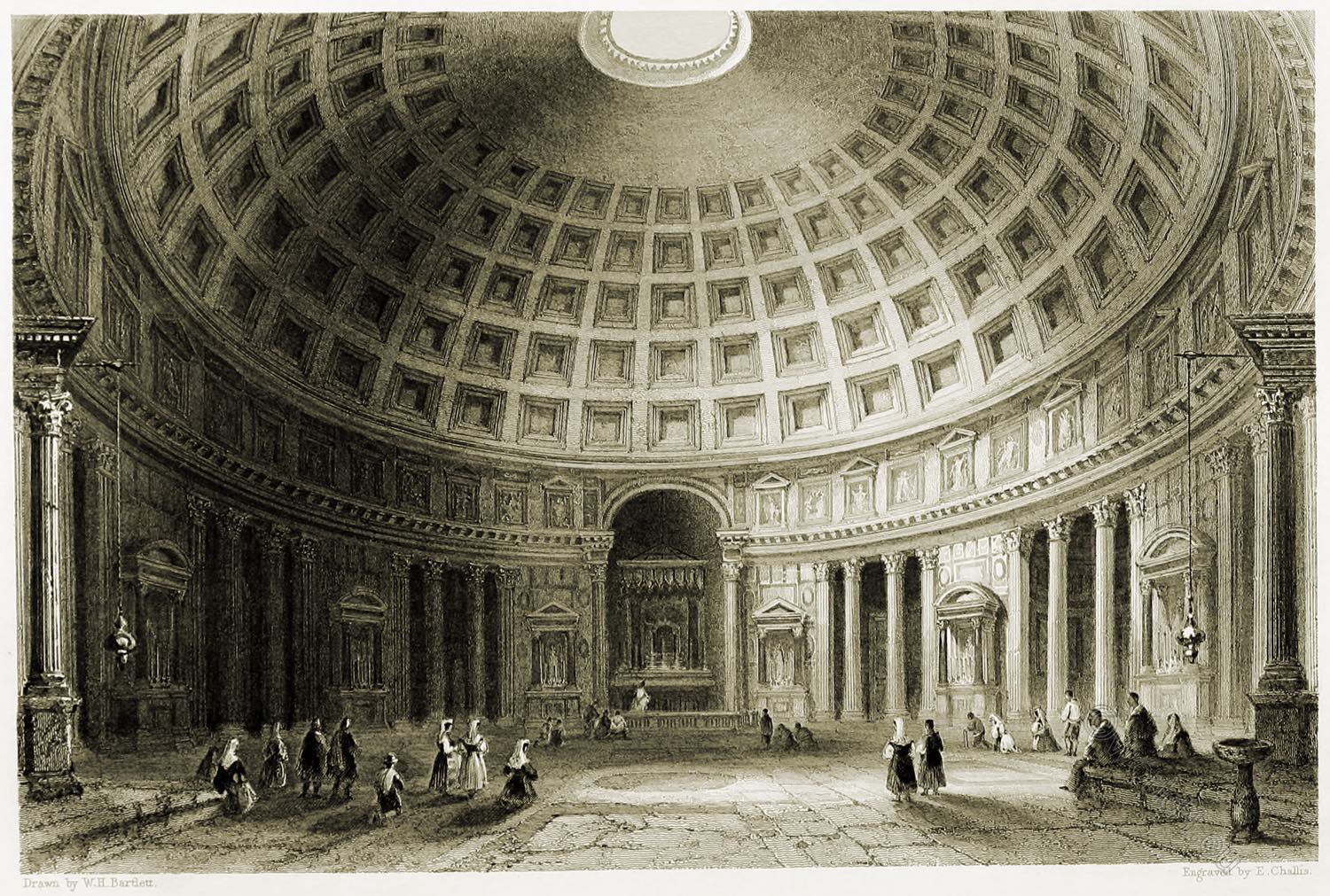

THE PANTHEON.

ROME.

"Simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime -'

Shrine of all saints, and temple of all gods,

From Jove to Jesus—spared and blest by time;

Looking tranquillity—while falls or nods

Arch, empire, each thing round thee, and man plods

His way through thorns to ashes. Glorious dome

I Shalt thou not last? Time's scythe and tyrant's rods

Shiver upon thee. Sanctuary and home

Of art and piety — Pantheon! —pride of Rome,"

From: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage by Lord Byron (1788–1824)

The Roman Pantheon is the most perfect specimen of ancient art in existence, the most magnificent evidence of the refinement of that nation which time has spared to posterity. The idea of a temple to all the Gods was itself ambitious, and the sumptuousness with which the comprehensive thought was embodied, is a model for after ages in the execution of public works. Athens had its Pantheon, but the Roman emperor Adrian was its founder, and Paris has raised a grand mausoleum to the shades of the people’s demi-gods, which is amongst the noblest monuments of modern times.

In front of the Church of the Pantheon at Rome is a piazza, adorned with a fountain, above which rises a sculptured obelisk of Egyptian granite, and around this beautiful embellishment a common market is daily held. The noble portico of Agrippa consists of a double row of Corinthian columns, of oriental granite, sixteen in number, and fifteen feet in circumference. This chef-d’oeuvre of ancient art displays a prodigious knowledge of statics, and presents an endless variety of festoons, paterae, candelabra, and other raised basso-relievos, all of exquisite performance.

The grand simplicity of the facade has been violated by the vulgar taste of Pope Urban VII. who compelled Bernini to erect the two little spires that rise above the pediment at either end, and which the Italian architects have deservedly compared to “asses’ ears.” The space between the two central pillars, wider than the other intercolumniations, opens an avenue to the celebrated brazen portal, the beautiful valves of which, as they unfold, disclose to view the noble rotunda so consecrated by antiquity, and by the mastery of art which it exhibits.

In niches, on each side of the portal, were colossal statues of Agrippa and Augustus, the emperor being unwilling to be ranked amongst the gods. The majestic interior retains much of its antique lining of precious marble, and, being more judiciously disposed than St. Peter’s, of which it was the prototype, deceives, by the appearance of greater magnitude than it possesses. The pavement is also ancient and perfect; it consists of porphyry, and Egyptian granite, and, were it the only relic of ancient art which expiring Rome bequeathed to after ages, would be sufficient to establish her claims to a just appreciation of beauty and magnificence of style. Eight niches received the effigies of so many of the dii majores, between which stood as many pedestals for the support of inferior deities.

Constantine carried away the sacred statues to his new capital—Adrian erected noble pilasters in the vacancies, and Pope Boniface IV, when he consecrated the Pantheon to all the martyrs, placed eight altars where the pedestals stood, enclosed between two marble pillars of diminished proportions.

A cornice of white marble runs round the whole rotunda, sustained by sixteen columns, and by as many pilasters of Giallo antico, and this beautiful circle is the rim from which the glorious dome, of solid stone, arises to the height of 137 feet, the exact diameter of the temple itself. The light descends upon the floor in one bright flood, through an opening in the dome of twenty-seven feet diameter, and the effect of this arrangement, when the brazen doors are first thrown open for admission, is truly astonishing.

At night the effect of the moon’s rays through the lantern of the cupola, and of the fleecy clouds which float in the sky, and pass over the silvery disc of our satellite, is curious and interesting. It is like the passing visions of a dream. The encircling walls of the Pantheon are believed to be republican architecture, but the porch and portico are uniformly ascribed to Agrippa: — Domitian and Severus contributed to its decoration; Genseric, the Vandal, plundered it of some of its bronze ornaments, but Constantine, the son of Heraclius, in the seventh century, so completely despoiled it of its antique embellishments that he has been designated by indignant history “the scourge of Rome.”

The Pantheon itself is an object of so much beauty, excellence, and admiration, that works of art, when placed within it, lose too great a portion of their fair and deserved applause. One coincidence is extraordinary,— the greatest artist of modern ages, Raffaelle, begged that no other tomb might be placed above his remains than the cupola of the Pantheon,— the monument is suited to the man.

Lorenzetto, under the overwhelming impulse of ardent friendship, ventured to place his beautiful statue of the Madonna del Sasso as a guardian angel of the great painter, and the bones of Annibal Caracci have also been laid within the sphere of the same vain tutelage. Thorswalden too, had the good taste to avoid all meritricios ornament, all rivalry of attraction,in the simple cenotaph, with a beautiful and life-like bust, which he has placed here to the memory of Consalvi.

The form, effect, and whole design of this admirable monument are most distinctly understood by an introspect from the opening of the cupola. When Charles V. visited Rome, in 1536, he desired to be conducted to the exterior of the cupola, for the purpose of looking down upon the Pantheon’s symmetrical proportions; Crescenzi, a young Roman gentleman, was appointed to be his guide, and discharged the honorable trust with becoming grace. Upon his return home, however, he confessed to his father that he felt inclined to have thrown the emperor down upon the pavement, to revenge the sack of his native city just nine years before, “my son,” replied the modern Roman, “such things should be done, not talked of.”

Source: The Rhine, Italy, and Greece in a series of drawings from nature by George Newenham (1790?-1877). London: Fisher 1841.