1 2 3 4 5

6 7 8

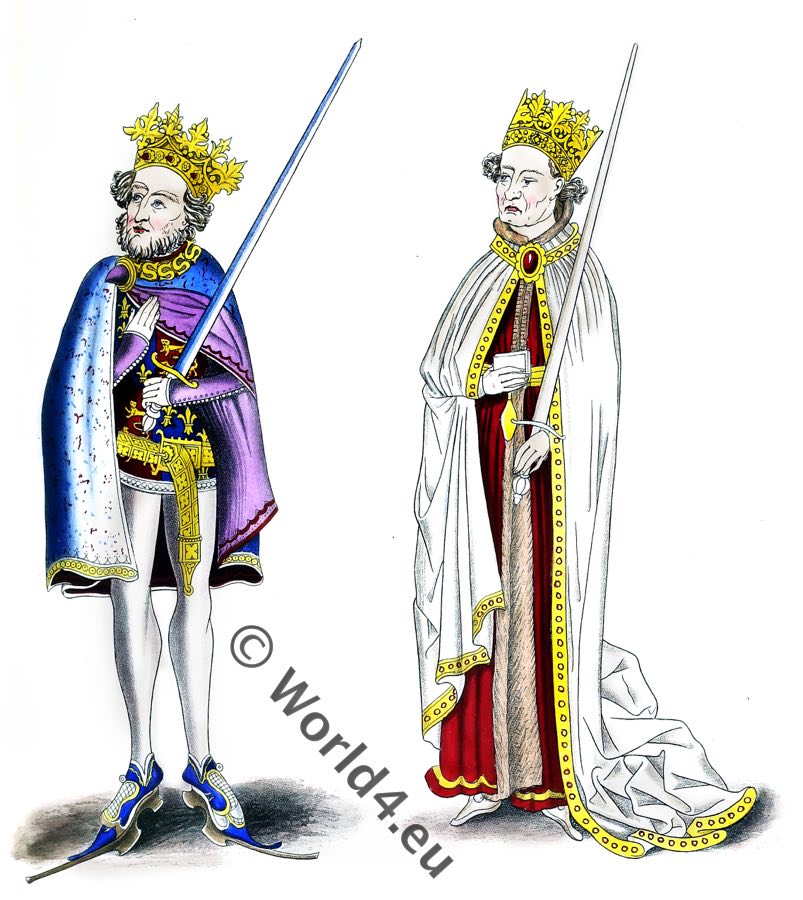

FRANCE 17TH CENTURY. THE COSTUMES OF THE ARISTOCRACY; 1646-1670. THE KINGS OF FASHION.

- Nos. 1 and 5, noblemen of the entourage of Renée du Bec, Marshal of Guebriant,

- No. 2. Page of the same lady.

- No. 3. René Crespin Du Bec, Marshal of Guébriant. Ambassadrice extraordinaire, special ambassador at the court of the Polish king Wladislaw IV. 1)

- No. 4. Anna Budes, Miss of Guébriaut.

- No. 6 and 8 Louis XIV, 1660 and 1670.

- No. 7. Maria Theresa of Austria, his wife 1660.

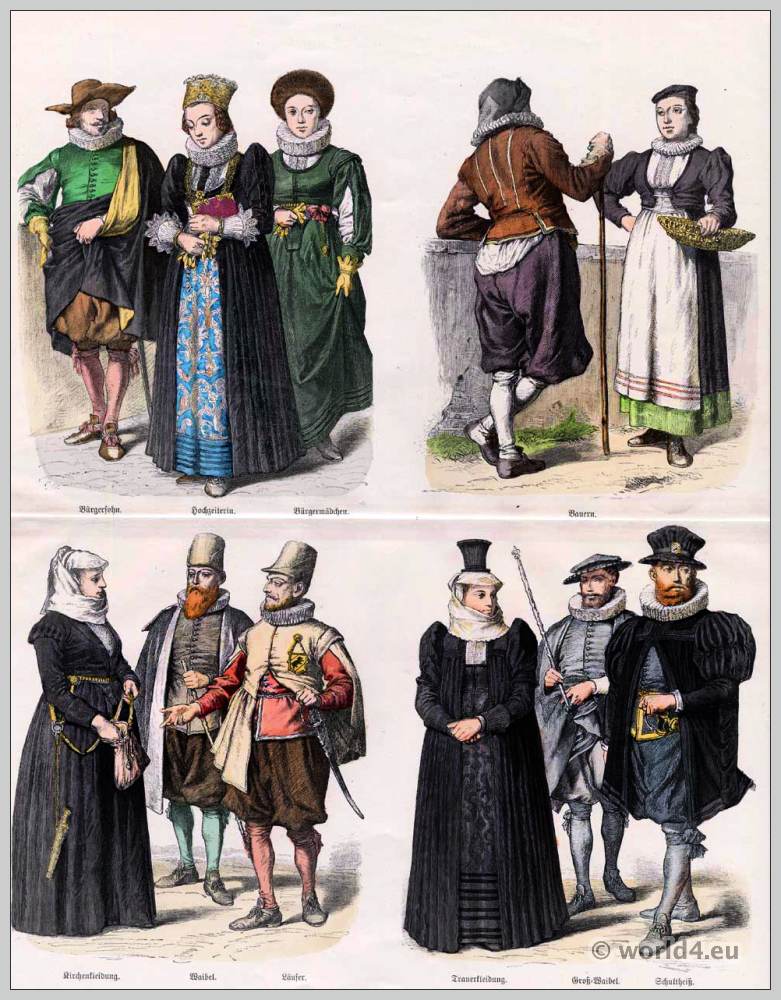

Twenty years after Roger de Saint-Lary, Duke of Bellegarde, Grand Stable Master of France (Grand Ecuyer de France), Monsieur le Grand, as he was called, had set the tone at the court, Montauron and, after him, Candale took power in the realm of fashion. From 1648 onwards, political events exerted a decisive influence, with fashion à la Fronde, à la paille, au papier being worn. Of the male costumes of our panel, 1, 2 and 5 still belong to the Montauron regime (Pierre Puget de Montauron, a leading financier of the day); No. 6 falls under the rule of the Duke de Candale.

No. 1. High conical hat with blunt tip and narrow brim, gold cord and falling feathers. Small folded collar. Short doublet showing a stripe of the shirt at the height of the belt. Slit sleeves and double-folded cuffs held together by a black velvet ribbon. Short trousers, decorated on the belt and at the bottom with rows of ribbons, the so-called galants. Stockings of English silk. Short coat, as usual, draped over the arm.

The lace was forbidden by an edict of 1644. For the trimming of the footwear, this prohibition was circumvented by giving it a new name. The “cannons”, first introduced under Charles IX, were given a different shape under Louis XIII. They were broadly turned under the calf and occupied with a double or triple fraise by Battist, Dutch canvas and Genoese lace. The long foot was truncated at the tip, the heel high and dyed red. In addition, spores of solid silver were worn, the shape of which changed as often as possible.

No. 5. Costume of similar cut. Coat with sleeves, lying on both shoulders. Seams and weir hangers richly embroidered with gold.

No. 2. The grègues on average of the 16th century remained in fashion for the costume of the pages. They were so tight that the term culottes was used for them. The upper part of it was puffed and decorated with the bows of the galants. A rich bandelier, silk stockings, delicate boots and a coat worn on one shoulder completed the costume. The fashion of long hair was maintained after it had been shorn for a while in 1645 in honour of the Swedes. The moustache was worn à coquill. It was ruffled at the tips with the help of a small instrument called bigotère after the Spanish bigotera.

Nos 3 and 4. The Marshal of Guébriant and his niece. The deep neckline of the robe is covered with a tulle-like collar to which Anna of Austria first added a lace trimming. Mrs. of Guébriant is still depicted here in widow’s mourning in 1646, three years after the death of her husband. She wears a large cross on her neck and a clock on her belt. The trimming consists of a simple silk peasant lace, called gueuse, with which one combined at most some real or fake pearls. The costume of the Miss of Guébriant is subdivided from that of her aunt only by the colors and the dressing up.

No. 6 and 8 Louis XIV 1660 and 1670. The most striking innovation with this costume are the underskirt trousers, introduced by a Rhine count Salm in France and named after him rhingrave. They went down in vertical folds up to the knee and were there fastened with the lining by a cord. The doublet is not only excessively shortened so that the shirt is visible around the waist, but also loses most of its sleeves, which end far above the elbow.

The Rhingrave trousers.

The so-called Rhine Count’s trousers (French Rhingrave, English Petticoat breeches) were a kind of culottes for men, which in the middle of the 17th century between about 1650 and 1670 belonged to the clothing of the European aristocracy and partly also of the bourgeoisie.

The trousers consisted of a wrinkled, approximately knee-length ‘skirt’, under it a puffed up bloomers emerged, which was laced at the knees with ribbons. This included obligatory lavish decorations with colourful silk ribbons and bows, which were placed at the knees, belly and around the waist. The lower trousers could also be decorated with lace at the knees, as well as the cuffs of the shirt and collars. They wore a short doublet, sometimes open at the front, under which the puffy white, lace-trimmed shirt stood out. Also silk stockings and shoes with high heels. Also on sleeves, shoulders and shoes ribbons and bows – all in the same colour, with preference in red. Sometimes a wide sleeveless coat (or cape) was placed over the shoulders.

The new trouser fashion is said to have been introduced in Paris around 1660 by the Dutch envoy Karl Florentin zu Salm, who bore the title of nobility of a Rhine count. The French aristocracy at the court of Versailles quickly adopted the new fashion, and since the entire European nobility was fashionably oriented towards the court of Louis XIV, the Rhine Count’s trousers were soon also worn in England, Germany and Holland.

Instead of his natural hair, Louis XIV did not adopt the wig until 1673. He enlarged the collar and connected it to a cravat with hanging ends. The puffed shirt became a lace-trimmed jabot. A myriad of ribbons and laces were also used to decorate the entire costume down to the shoes, which gradually replaced the jackboots. The upper covers of the latter replaced long lace cuffs attached to the garter straps.

In 1660 Louis XIV is depicted without a sword, but already in 1670 the same was worn again on a wide embroidered and fringed bandolier. The costume of 1660 is still influenced in its simplicity by Mazarin and his laws of luxury. In 1664 the permission to use brocade fabrics and lace was made dependent on a special patent to be granted by the king. Only the princes were exempt from the patent.

No. 7 Maria Theresa of Austria, 1660. Closed, strongly decolleted bodice, the neckline decorated with linen or gauze and wrapped in a rich collar. Short sleeves, from which twofold divided line puffs extend down to half of the forearm by loops. The decoration consists of galants or faveurs, a kind of ribbons that cover the edge of the manteau, which ends in a train. There is also such a loop at the level of the vertex. Maria Theresa had a penchant for jewellery made of pearls and rubies and knew how to apply them lavishly but with great taste.

1) Tischer, Anuschka: A French ambassador to Poland 1645-1646. Renée de Guébriant’s legation to the court of Wladislav IV, in: L’Homme: European Journal of Feminist History.

Figures from the collection of Gaignères, in the copper engraving cabinet of the National Library in Paris. See M. Quicherat, Histoire du costume en France.

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.