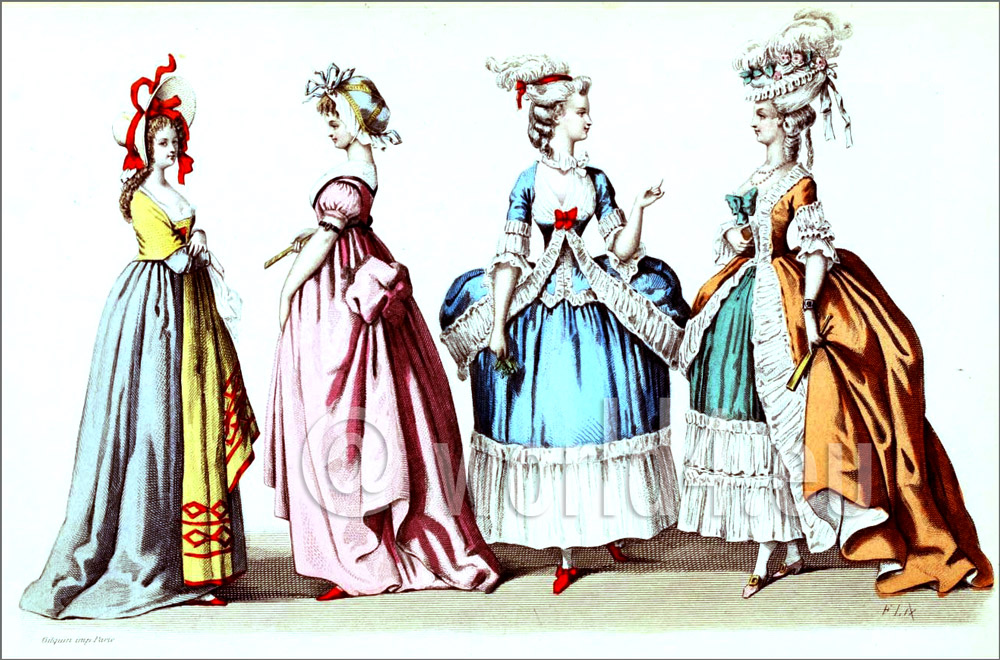

The Reign of Louis XVI. 1774 to 1780.

Content: Letter from Maria Theresa – Leonard and Mdlle. Bertin – Various styles of head-dresses. The Hérisson or the Hedgehog hairstyle – “Pouf” – “The Journal de Paris” – Reign of Louis XVI. – Male and female hairdressers -Plumes – Hair worn low – The queen’s puce – colored gown; shades of color in dresses – Oberkampf and the Jouy prints – Expensive satins- Trimmings, their great number and importance – Gauze, blond, tulle, and ribbons – Some kinds of shoes – Venez-y-Voir – The “Archduchess” ribbons – A dress worn at the opera.

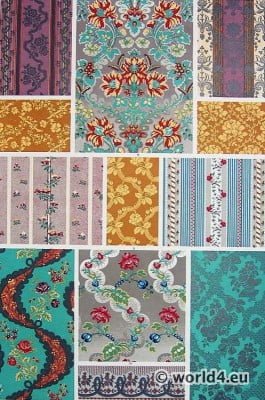

By the end of the eighteenth century heavy materials had fallen from favor and less metallic effects were sought in weaving, but oriental foliation, which was used before and during the Renaissance, again came in. Under Louis XVI the designers followed innumerable paths under the impulse of capricious fashion. We have Arabesque composition, foliage, flowers, figures, landscapes, country scenes, allegories and Chinese ornament.

In the fabrics we find stripes and ribbons combined with flowers. Stripes were so much used that in 1788 it was said that, “Everybody in the king’s cabinet looks like a zebra.” Unlike the Pompadour stripe, the Queen Marie Antoinette stripes were interwoven with flowers and ornaments such as feathers, medallions, lyres, columns, etc.

Marie Antoinette liked flowers, the pink, the tulip, but best of all the rose, and the impetus she gave the production of lace in the beginning of her reign shows the influence of her taste, which is everywhere seen in the entwined ribbons and garlands.

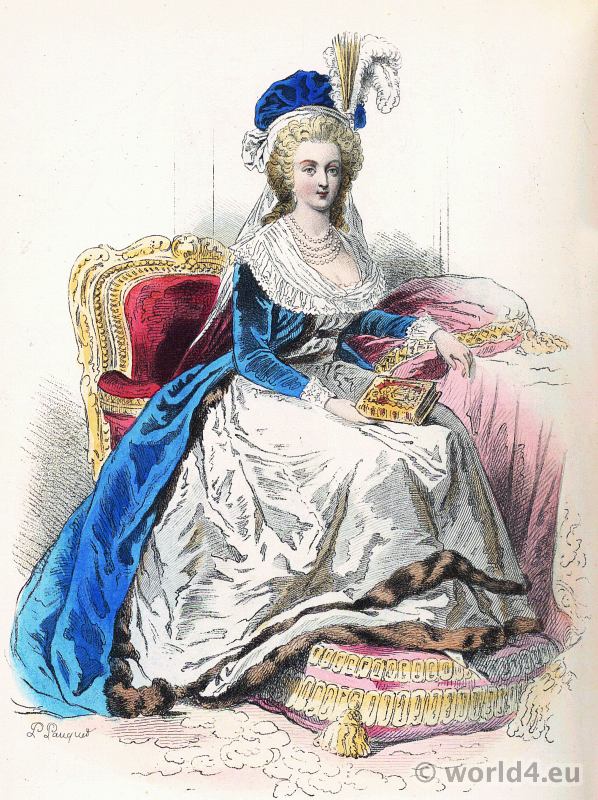

The influence of Marie Antoinette on fashion.

WE have now reached the reign of Louis XVI., when Marie Antoinette was holding her court. She had already begun to set the fashion when only Dauphiness. One day, in 1775, the new queen took up from her dressing-table two peacock feathers, and placed them with several little ostrich plumes in her hair. Louis XVI came in, and greatly admired his wife, saying he had never seen her look so well.

Almost immediately feathers came into fashion, not in France only, but throughout Europe. But when; shortly afterwards, Marie Antoinette sent a portrait of herself, wearing large feathers as a head-dress, to her mother, the Empress Maria Theresa returned it. “There has been, no doubt, some mistake,” wrote Maria Theresa; “I received the portrait of an actress, not that of a queen; I am expecting the right one.”

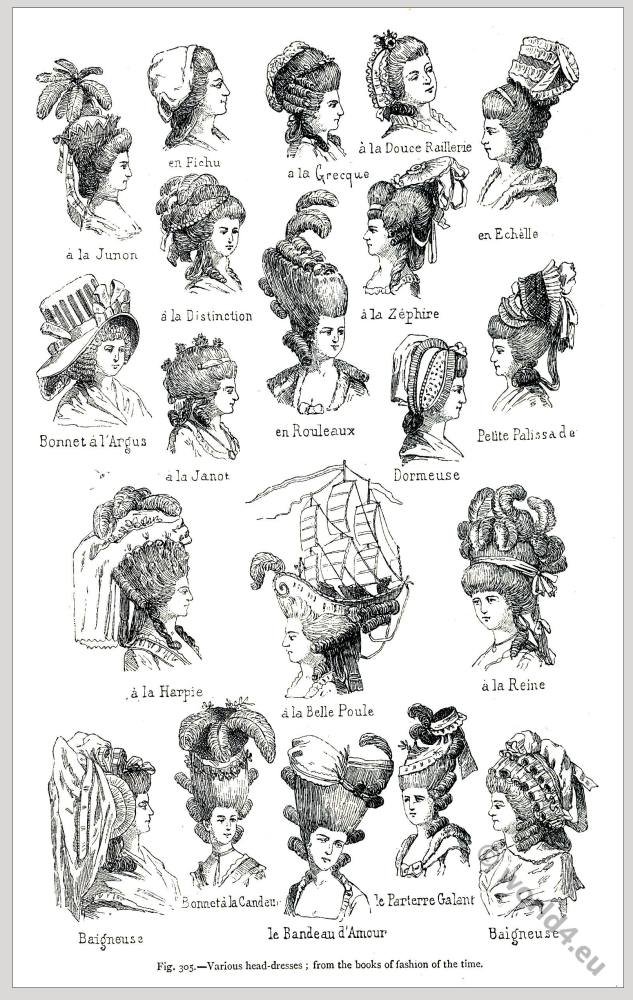

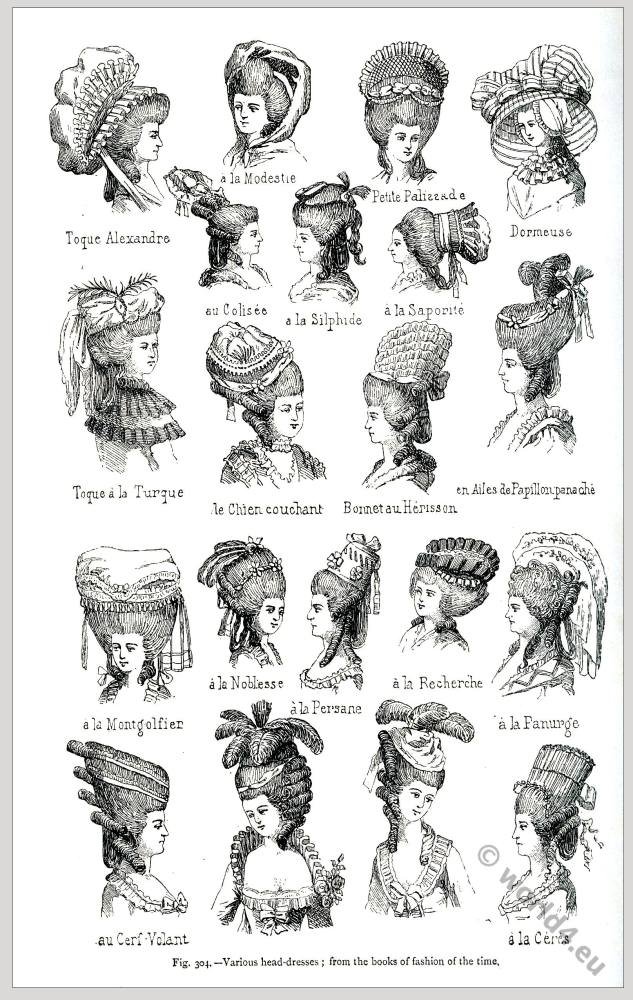

Various styles of head-dresses.

This severe rebuke had no effect. Before 1778 the hair had been so arranged as to form a point in front, called à physionomie, accompanied by attentions, or thick, separate curls. But in 1778 the queen invented the hérisson, or hedge-hog style of head-dress.

Imagine a porcupine lying on the top of the head, that is to say, a bush of hair frizzed from the points to the roots, very high and without powder, and encircled by a ribbon that kept this horrible tangle in its place.

This style of head-dress, somewhat modified, and reduced to a demi-hérisson, or half hedgehog, was in fashion for several years.

Marie Antoinette continued to invent new styles, such as “jardin a l’anglaise,” “parterre,” “forest,” “enamelled meadows,” “foaming torrents,” &c. How many ridiculous names were given to the inventions of ladies endeavouring to imitate and surpass their queen! The hair was dressed “butterfly” fashion, or “spaniels’ ears,” or “milksop,” or “guéridon,” or “commode,” or “cabriolet,” or “mad dog,” or “sportsman in a bush,” by turns.

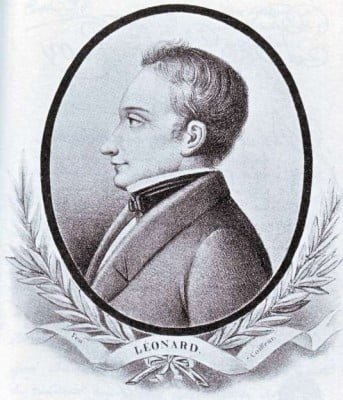

Mdlle. Rose Bertin

At the clubs or in the public gardens, everyone talked in raptures of the achievements of Léonard, “Academician in coiffures and fashions,” and those of Mdlle. Bertin, a milliner who at a later period delivered herself as follows:- “The last time i worked with the queen, we decided that the new caps should not come out for another week.” A didactic mode of expression! Turgot or Necker could not have spoken more solemnly. It is true that Mdlle. Bertin’s fame had spread throughout Europe. In the “coiffure à la Dauphine” the hair was curled, and then drawn up from the forehead, falling at the back of the head; that called “monte-au-ciel” was of enormous size. In 1765, caps were worn “à la Gertrude,” so called from the opera-comique Isabelle et Gertrude, by Favart and Blaise; and in 1768, caps “à la moissonneuse” (the reaper) and “à la glaneuse” (the gleaner) came into fashion, copied from those worn in the opera of the Moissonneurs, by Favart and Duni.

Head-dresses named d’apparat (or state head-dresses) or loges d’opera (opera-box head-dresses) were seventy-two inches in height; they came in in 1772. Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide was performed in 1774. The singer who took the part of Iphigenia wore, when about to be sacrificed, a wreath of black flowers, surmounted by a silver crescent, and a long white veil flowing behind. Every lady immediately adopted the lugubrious coiffure à l’Iphigénie.

Now that we are on the subject of theatricals, I may mention that in 1778, Devismes, the director of the opera, made it a rule that only head-dresses of moderate height might be worn in the amphitheatre. The comet of 1773 gave its name to certain head-dresses, in which flame-colored ribbons played a striking part; in 1774 a “quésaco” head-dress was invented (This is a Provençal expression, meaning,” What does it mean?” or “What is it all about?”) consisting in part of a large bunch of plumes behind the head.

At court the pouf au sentiment was much in favor; it was composed of various ornaments fastened in the hair, viz. birds, butterflies, cardboard Cupids, branches of trees, and even vegetables. Louis Philippe’s mother wore a pouf in which everyone might admire the Duc de Beaujolais, her eldest son, in the arms of his nurse, a parrot pecking at a cherry, a little negro, and various designs worked with the hair of the Dukes of Orléans, Chartres, and Penthièvre.

The “coiffure à la Belle Poule” consisted of a ship in full sail, reposing on a sea of thick curls. In the Jeu des Costumes et des Coiffures des Dames, an imitation of the Royal Game of Goose, the winning number, sixty-three, was assigned to the Belle Poule.

The scaffolding of gauze, flowers, and feathers was raised to such a height that no carriages could be found lofty enough for ladies’ use. The occupants were obliged either to put their heads out of the windows, or to kneel on the carriage floor, so as to protect the fragile structures. This seems like a return to the reign of Louis XV.

In a letter addressed to the actors of the Italian Theatre, in January 1784, by Lenoir, the lieutenant of police, we read as follows: “There are constant complaints of the size of headdresses and hats, which, being loaded with plumes, ribbons, and flowers, intercept the view of spectators in the pit….” A number of caricatures, of which some – to the horror of all monarchists – actually reproduced the features of Marie Antoinette, were brought out in ridicule of the fashionable head-dresses.

Male and female hairdressers.

Hair-dressing was a difficult art, requiring time and labour. Country ladies employed a resident female hair-dresser in their house, by the year, and on the occurrence of any family festival she would be kept at work nearly the whole day.

In order to show the importance of this subject, we quote from the Journal de Paris of February 10, 1777, to which was added a supplementary engraving with the following explanation: “We add to our issue of this day an engraving representing two different dressings of the hair, back and side views; they are drawn from nature by a clever artist who has been kind enough to give us his assistance. The figures I and 2 refer to one of these methods, the figures 3 and 4 to the other.

If by this attempt we succeed in giving pleasure to those ladies who are included among our subscribers, we shall be happy to renew an expenditure that proves our zeal in their service.”

No satire was intended by the above publication. The Journal de Paris was a grave production, and the prints it published were of moderate head-dresses, if I may so express myself, of no excessive height, powdered, and such as might be worn by bourgeoises without appearing extraordinary.

Besides the fashions we have described, there were others from 1774 to 1789, viz. Grecques à boucles badines (or Greek with playful ringlets), à l’ingenue, à la conseilliere, à l’oiseau royal, chien couchant, les parterres galants, les calèches retroussées, and many others, the description of which would fill volumes. (It will not assist the reader’s imagination much to give the translation of these extraordinary names; but here they are: the ingenuous maiden, the counsellor’s wife, the royal bird, dog lying down, gallant pits, calèches with the hoods up.)

Marie Antoinette continued to rule the fashionable world; nor can we be surprised that the flattery of courtiership “took up the tale.” In honor of Louis XVI.’s accession, hats were invented under the name of “delights of the Augustan age,” and a color called “queen’s hair,” of a pretty blonde tint.

For many years a great rivalry had subsisted between the male and female hair-dressers, and towards 1775 an amusing law-suit was commenced between the former and the wig-making barbers.

“We are,” contended the hair-dressers, “essentially ladies hair-dressers… . What are the duties of barbers? To shave heads, and purchase the severed hair; to give the needful plait by means of fire and iron to locks that are no longer living; to fix them in tresses with the help of a hammer; to arrange the hair of a Savoyard on the head of a marquis; to remove the attribute of their sex from masculine chins with a sharp blade; all these are purely mechanical functions that have no connexion with our art… .“

They went on to say that the art of dressing women’s hair was nearly allied to genius; and that in order to exercise it nobly, one should be at once a poet, a painter, and a sculptor. “It is necessary to understand shades of color, chiaro oscuro, and the proper distribution of shadows, so as to confer animation on the complexion, and make other charms more expressive. The art of dressing a prude, and of letting pretensions be apparent, yet without thrusting them forward; that of pointing out a coquette, and of making a mother look like her child’s elder sister, of adapting the style of dress to the disposition of the individual, which must sometimes be guessed at, or to the evident desire of pleasing… in fine, the art of assisting caprices, and occasionally controlling them, requires a more than common share of intellect, and a tact with which one must be born.”

I am not drawing on my imagination. The memorial of the ladies’ hair-dressers is still in existence, and bears the names of the procureur and advocate-general of the time. The artists in hair exclaim in poetical accents, “If the locks of Berenice have been placed among the stars, who shall say that she reached that height of glory unaided by us”! They vaunt their honesty: “The treasures of Golconda are continually passing through our hands; it is we who decide how to arrange diamonds, crescents, sultanas (a particular form of necklace), aigrettes.” They compare themselves to heroes: “A general knows how to take advantage of a demi-lune in front of his position – in the van, he has his engineers; we, too, are engineers so far; a crescent advantageously placed by us is hard to contend against, and it seldom happens that the enemy does not surrender at discretion! … A lady’s hair-dresser is, as it were, the first officer of the toilet… and under his artistic hands, amid his artistic influences, does the rose expand and acquire her most brilliant beauty.”

The conclusion to be drawn is that wig-makers and their assistants are evidently unfit to dress the hair of women. The law proceedings, however, did not prevent the competition of wig-makers and female hair-dressers, even at the period when all trade guilds were suppressed.

The toilet of the queen of France was a masterpiece of etiquette.

“The toilet of the queen of France was a masterpiece of etiquette, according to Mme. Campan. First was the chambermaid of (French première femme de chambre) Marie Antoinette. After the death of Marie Antoinette, she founded in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a boarding school for girls who attended Napoleon’s stepdaughter Hortense de Beauharnais.

1822 or 1823 her famous memoir, Memoires sur la vie privee de Marie Antoinette, suivis de souvenirs et anecdotes historiques sur les règnes de Louis appeared XIV-XV, a revealing insight into the life of the French aristocracy before the revolution, particularly for the necklace affair, give; everything was done by rule: the lady of honor and the lady of the bedchamber were both present, assisted by the first dresser, and two others who did the principal part of the service; but there were distinctions to be observed. The lady of the bedchamber (dame d’atours) put on the queen’s petticoat and handed her gown, the lady of honor poured out water for washing the royal hands, and put on the queen’s chemise”.

Marie Antoinette carried the fashion of “panaches” or plumes to an extreme. If we may believe Soulavie’s memoirs of the period, “when Marie Antoinette passed through the gallery at Versailles, one could see nothing but a forest of waving plumes a foot and a haIf higher than the ladies’ heads.” The king’s aunts, who could not make up their minds to follow such extraordinary fashions, nor to copy the queen’s dress day by day, used to call her feathers “ornaments for the hair”.

The majority of the court ladies, however, imitated the queen. Hats and caps were so overladen with feathers, that not only were coaches too small to contain the plumed dames of the period, but ladies were fain to bend their heads in the “entresols” of certain suites of rooms, because of the lowness of the ceilings. “Nevertheless,” says a lady of the court, “it was a fine sight to see that forest of plumes in the Versailles Gallery, waving with gown, old puce, young puce “ventre de puce” (flea’s belly), “dos de puce” (flea’s back), &c.

As the new color did not soil easily, and was therefore less expensive than lighter tints, the fashion of puce gowns was adopted by the bourgeoisie, and the dyers were unable to meet the pressing requirements of their customers.

The queen’s puce.

During the reign of Louis XVI., many new colors were worn, either in combination or successively, such as puce, rash tears, Paris mud, Carmelite, entraves de procureurs (procureur’s tricks), &c. These were all quiet colors, and were used for simple costumes.

In 1763, the Opera House was burnt down; and the fine ladies would wear nothing but “couleur tison d’opéra,” or “brand from the opera;” in 1781, they held to “opéra brûllé,” or burnt opera-house. I should find it difficult to describe these two shades otherwise than as flame-colored.

After the performance of Athalie at the Court Theatre, in 1780, (Athalie is the final tragedy in five acts by Jean Racine from the year 1691) women of fashion wore the Jewish Levitical tunic; and shortly after the opera of Atys (by Quinault and Lulli) had resumed its place on the stage, they dressed their hair “à la doux sommeil” (gentle slumber).

Louise-Rosalie Lefebvre (Artist name Madame Dugazon), * 1755 in Berlin, † 1821, was a French stage actress, dancer and singer) in Blaise et Babet, an opera by Nicolas-Alexandre Desède (1783), wore a blue silk skirt shot with pink, and shot silks became all the fashion. In 1786 the same actress set the fashion of caps “à la Nina,” from Nicolas Dalayrac’s opera of that name. “Coiffures a la creole” were worn next, made of Madras handkerchiefs, like those in Kreutzer’s opera of Paul et Virginie; and lastly, hats “à la Primerose,” from another play of Dalayrac’s.

Oberkampf and the Jouy prints. Expensive satins, gauze, blond, tulle, and ribbons.

During many years of the reign of Louis XVI the court of Versailles was ignorant of the very name of Oberkampf, a manufacturer who had at last (1759) obtained permission to establish a factory of colored prints (indiennes) near Versailles. (Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf 1738-1815, one of the best manufacturers of printed cotton cloth in Europe, the most famous textile designer its time working for him, many of the designs are now in the Musée de la Mode et du Textile in Paris).

A mere accident made him suddenly famous. A certain great lady, whose Persian cambric was the envy of all the princesses, had the misfortune to tear it. She hastened to the factory at Jouy-en-Josas, near Versailles, and claimed the help of Oberkampf, who succeeded in his efforts to produce a similar gown, and whose name was immediately in everyone’s mouth. The ladies at Versailles would wear nothing but Jouy cambrics; and from that time prints have been constantly worn by the women of the people, but they are seldom seen at the present day.

Gowns trimmed with one material only were much in favor; straw-colored satin was very much used. These dresses were trimmed in various ways, either with gauze, lace, or fur. There were innumerable varieties of trimming, besides brocaded or painted satin, and each had its own special name.

The most fashionable tint for satin was either “soupier étouffe” (stifled sigh), or apple-green with white stripes, called “vive bergère” (the lively shepherdess).

Some of the names given to trimmings are curious, and remind us of the “précieuses” of the Hôtel de Rambouillet. Such are: “indiscreet complaints,” “great reputation,” “the unfeeling,” “an unfulfilled wish,” “preference,” “the vapors,” “the sweet smile,” “agitation,” “regrets,” and many others.

Paniers were generally small, but padded at the top. Shoes, either puce color or “queen’s hair,” were embroidered in diamonds, and women’s feet might be compared to jewel-cases. Long narrow shoes, with the seam at the heel studded with emeralds, were called in the trade “venez-y-voir,” or “come and see.”

Women wore over their shoulders an arrangement of lace, gauze, or blond, closely gathered, and called “Archiduchesse,” or “Médicis,” or “collet monté.” Tulle was in great request, and was manufactured everywhere.

As for ribbons, the most fashionable were called “attention,” “a sign of hope,” “a sunken eye,” “the sigh of Venus,” “an instant,” and “a conviction.” Sashes were worn “á la Praxitèle,” an opera by Devismes. Once more we are reminded of Molière’s “Précieuses.”

A dress worn at the opera.

A great sensation was caused at the opera one night by the arrival of a lady dressed as follows. Her gown was “a stifled sigh” trimmed with “superfluous regrets,” with a bow at the waist of “perfect innocence, “ribbons of “marked attention, “and shoes of “the queen’s hair” embroidered in diamonds, with the “venez-y-voir” in emeralds. Her hair was curled in “sustained sentiments, “a cap of “assured conquest” trimmed with waving feathers and ribbons of “sunken eye,” a “cat” or palatine of swans’- down on her shoulders of a color called “newly-arrived people” (parvenus), a “Médicis” arranged “as befitting, “a “despair” in opals, and a muff of “momentary agitation.” Since that evening how many extraordinary costumes have been displayed at the opera, and have attracted the attention of the fair spectators!

By Augustin Challamel

Source:

- The history of fashion in France, or, The dress of women from the Gallo-Roman period to the present time by Augustin Challamel, Frances Cashel Hoey, John Lillie, 1882.

- Costume design and illustration by Ethel Traphagen. New York, London: John Wiley & sons, inc. 1918.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.