Ancient Greece. The Women’s toilet.

Lucian gave us a detailed description of the toilet of the Greek women in his conversations about love, which is further illustrated by the antique vase pictures. Before the actual toilet began, body washes were carried out in a bowl on a high podium ( No. 1, 2 and 16).

The water in this bowl was perfumed with fragrant essences poured from small bottles and vessels (lekythos, alabastron, phiale) of metal, glass, alabaster, etc..

Apollonios of Kition wrote a treatise on the fragrances, the citation of which in Athenaeus of Naucratis shows that the cosmetics of the Greeks or women of the Hellenes were very extensive and that the beauty products were made in different areas.

Among others, sword iris extract from Elis or Cyzicus, rose extract from Phaselis, Naples and Capua, saffron extract from Soli in Cilicien and Rhodus, nard essence from Tarsos, vine leaf extract from the island of Cyprus and from Hadramyttium (Adramyttion), marjoram and apple perfume from the island of Kos, plum essence from Egypt, Phoenicia and Sidon have been handed down. The Panathenaeicum, which was only produced in Athens, was accompanied by an extract of bitter almonds, which only the Egyptians understood how to produce.

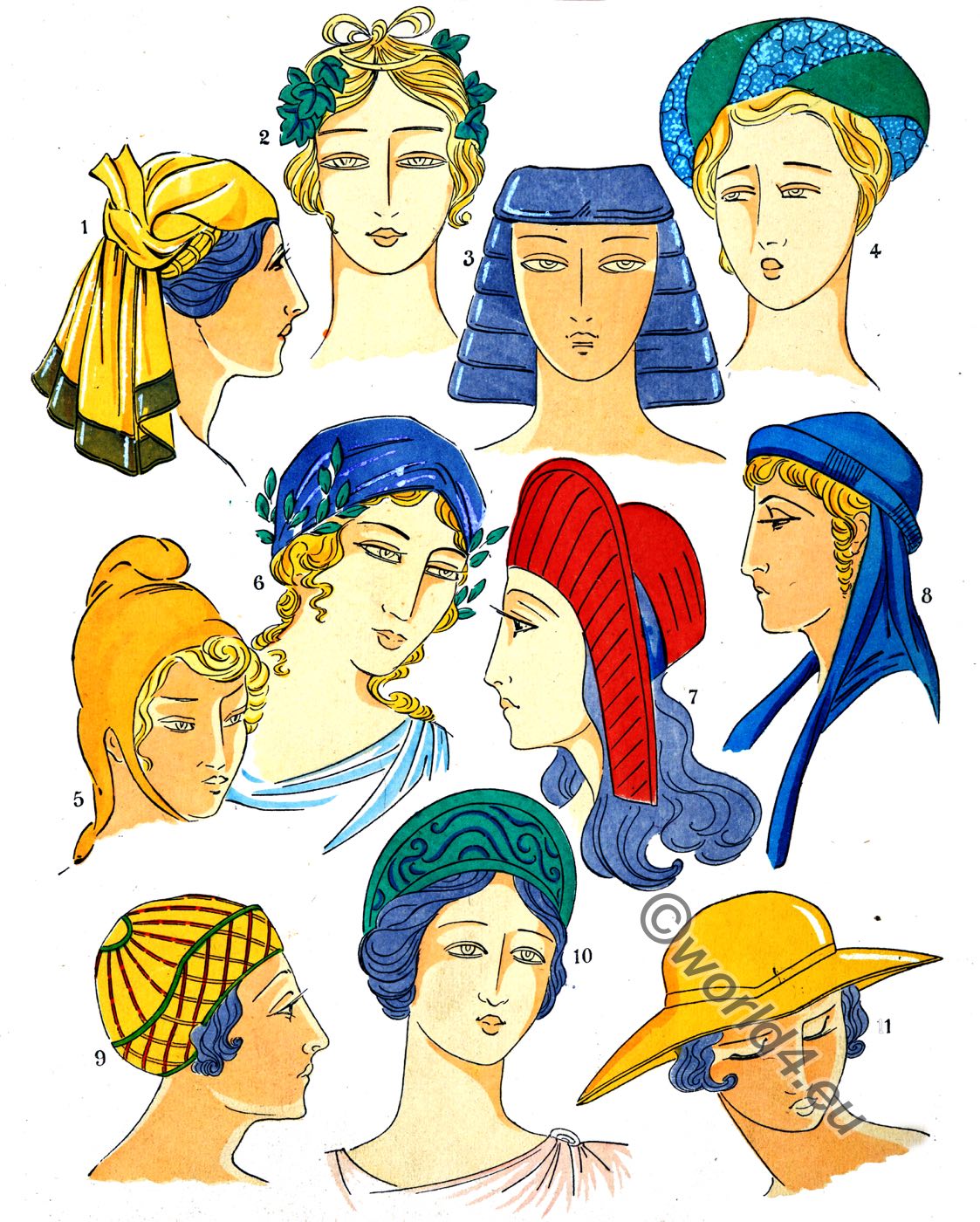

The figures Nos. 16, 1 and 2, 19 and 20 show the first phases of the female toilet. The first figure washes her hair standing to clean it of the color or powder of the previous day. The hair was dyed black like ebony or with dazzling colours, like that at the neck of a dove, or azure blue like the sky and the waves of the sea or blond, like the honey of Attica or Sicily, as Apulejus says. Or the hair was powdered with gold dust, white or red flour. In addition to dyed or powdered hair, eyebrows were naturally dyed black.

The Greek women devoted the most embarrassing care to their hair. “In the care of their hair,” says Lucian, “they exhausted their knowledge by making their hair as shiny as the sun at noon, dyeing it like wool, and using all the scents of Arabia to perfume it.” In Lucian’s time, the hair was first washed with lye to dye it blond, then rubbed with a pomade made of yellow flowers and left to dry. The hair of woman number two seems to have already dried. She looks into a convex mirror while the servant pours water into the basin. Nos. 19 and 20 are a manipulation of the washing up.

On group 3 and 4 the mistress has already finished her toilet and looks pleasingly into the mirror. To the completion of her head-cleaning, a servant hands her another Tainia (headband, ribbon, or fillet.) to it. The same is done by the servant No. 18. Such Tainia, which appear countless times on vase pictures, are also depicted under No. 9, 11, 12, 13 and 22. These Tainia were mostly used for the headdress.

However, among those depicted there may also be those that were used as belts over the robes or as bust bandages on bare bodies to maintain breasts. Figure 17 shows that the flap of the chiton was held in place by a band around the hips.

Among the most indispensable toilet equipment were, of course, mirrors and jewelry boxes. There were flat and concave, round and elliptical mirrors. The oldest were made of copper. The numbers 4, 5 and 21 show hand mirrors that could be hung on eyelets. A jewellery or toilet box can be found at No. 2 and Figure 21 holds such a mirror in his hand on a braided hanger.

The fan, the flabellum of the Roman women and the skepasma of the Greek women, could not be folded (nos. 6, 7, 8, 10, 14, 15 and 22). It was stiff and had a more or less long style, depending on whether it was intended for self-use or for handling by a servant for the supply of fresh air. The fans were sometimes made of peacock feathers, which were lined up like rays. The fans often had the shape of lotus leaves. The parasols had the shape of today’s parasols and were closed in the same way with the help of poles. They were made of various materials, including silk. They were usually held over the heads of their mistresses by servants. During the Panathenian procession (The Panathenians) in Athens, the daughters of the Metocene had to wear the umbrellas for the bourgeois daughters.

(After antique vases, published by Willemin in his works: Costumes des peuples de l’antiquité)

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

[wpucv_list id=”136457″ title=”Classic grid with thumbs 2″]Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.