Art in England during the Elizabethan and Stuart Periods. Textiles and Embroidery by Aymer Vallance.

CHAPTER V

TEXTILES AND EMBROIDERY.

THE manufacture of tapestry hangings was brought to such perfection on the continent, and the ease with which they could be rolled up and transported such that there does not seem to have been any attempt to produce them at home throughout the middle ages, nor previously to the time of Queen Elizabeth.

Thus the magnificent series of tapestries purchased by Cardinal Wolsey for his palace of Hampton Court were all woven abroad.

It is explicitly recorded that the first to introduce at his own cost into England the art of weaving tapeta was a Warwickshire gentleman, named William Sheldon. In the latter half of the sixteenth century he commissioned one Richard Hicks to visit the Low Countries for the purpose of studying the several processes of the craft of weaving.

On the latter’s return from his travels, tapestry looms were accordingly set up at Weston, where the Sheldon estates lay, and at the Manor House at Barcheston, the home of Sheldon’s wife’s family.

In his will and final directions, dated 1569 and 1570, William Sheldon describes Richard Hicks as “the only author and beginner of this art within this realm.”

And in the same document also he sets forth the motives which led him to establish the weaving industry in this country. Adam Smith was yet unborn, and Sheldon therefore did but express the current economic ideas of his day when he declared that to do as he had done was to confer a public benefit, not only as providing profitable employment for young people, but also because it must prove “a means to secure great sums of money within this realm”-sums that would otherwise “issue and go out of this realm” in the purchase of “the same commodities, to the maintenance” of foreigners and “to the hindrance of this commonwealth.”

Moreover, William Sheldon’s will directs that certain hangings of tapestry and arras, then at his house at Beoley, were to remain there as heirlooms in perpetuity. None of these works can now be traced.

After Richard Hicks, the factory at Barcheston was conducted by his son Francis, under whom, about the year 1640, a set or sets of tapestry are known to have been produced, consisting of woven maps of counties of England. They had nothing of the nature of ornamental design about them, except in the borders, which represent figures and plants under architectural arcades.

The only authenticated pieces of Barcheston tapestry surviving are five maps, which, after various vicissitudes (passing through the hands of Horace Walpole, among others) have now found a final resting place in the Museum at York and in the Bodleian Library.

ENGLAND. Second half of 16th century. Panel of fine canvas, embroidered with coloured silks and gold thread in tent stitch. The shield bears the arms of Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. In the possession of the Duke of Devonshire, K.G.)

Meanwhile, the Barcheston looms cannot long have been established before colonies of Flemish weavers, in 1567-8, settled in Kent, at Canterbury, Maidstone, and Sandwich, and in East Anglia at Norwich and Colchester, followed a year or two later, i.e., in 1570, by two Dutch arrasweavers at York.

But what is believed to have been the most formidable rival to the Barcheston tapestry works, and such that brought about the latter’s decline and eventual collapse, was the factory founded at Mortlake, under the patronage of James 1., by Sir Francis Crane, in 1619.

Belgian weavers were brought over to start the industry, and six of them are known to have been employed there in 1630. Sir Francis Crane was succeeded in the proprietorship by his brother Sir Richard, from whom the premises and goodwill were acquired and turned into the royal factory by Charles I.

In 1670 other tapestry-weaving works were established at Chelsea and Lambeth; and also, in the following century, at Fulham. To trace the subject further is outside the scope of the present work.

ENGLAND Second half of 16th century. Panel of canvas, embroidered with coloured silks in tent stitch of two sizes. There is a narrow velvet border, embroidered with couched tinsel. The central medallion shows two frog’s on a well-head and has the monogram of Mary, Queen of Scots, who worked the panel. (In the possession of the Duke of Devonshire, K.G.)

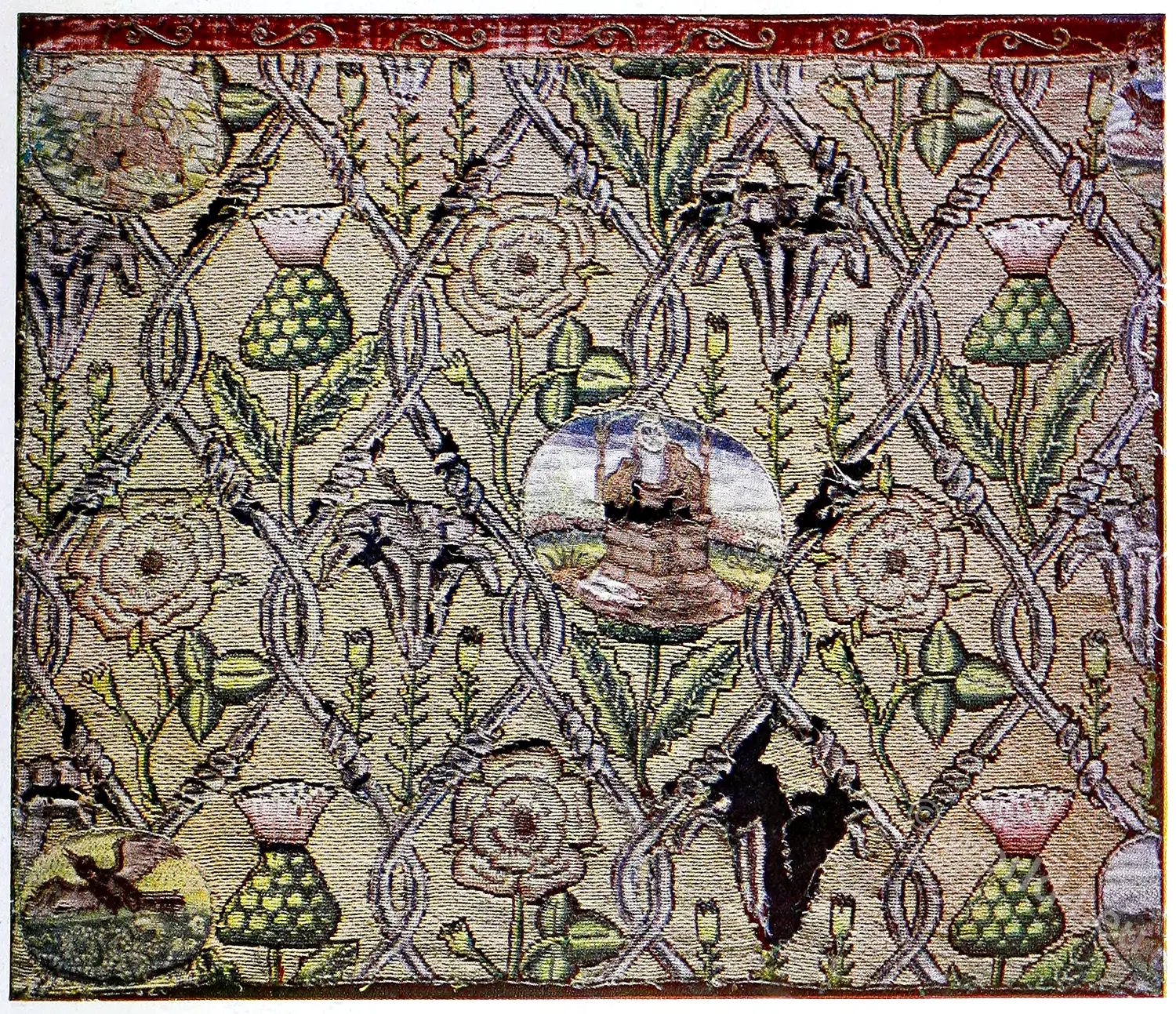

It rarely happens that any maker’s name or date was woven into the fabric, and so, when there is no other internal nor external documentary evidence of identification, it is rash to dogmatize as to the provenance of such a piece as that illustrated (page 99). It belongs to the class called “verdura,” subjects, that is, consisting of foliage with birds and beasts, but not human figures.

With its herbal-like treatment of plants, it probably dates from the latter part of the sixteenth or earlier half of the seventeenth century. It was at one time at the old Manor House at Hollingbourne, but is now at Sharsted Court, Doddington, Kent.

If tapestries were commonly imported into this country it is not less a fact that embroideries were of home product; the English needlework enjoying from the thirteenth or beginning of the fourteenth century a European reputation. And though the Reformation arrested the demand for embroidery for ecclesiastical purposes, the immense increase of domestic luxury gave a fresh stimulus to the secular phases of the art in the latter half of the sixteenth century and afterwards.

Queen Elizabeth’s own appreciation of the art of the needle was signalized by the incorporation, in 1561, three years after her accession, of the Broderers’ Company.

A fashion, introduced, it is said, from Spain by Catharine of Aragon, and resorted to as a solace in her troubles, was embroidery in black silk, sometimes enhanced with gold or silver thread, upon a ground of white linen. This kind of work continued to be popular down to the end of James I’s reign.

Larger pieces, for hangings and dorsers, like the three specimens reproduced, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, were executed in petit point in coloured silks, or silks and wools, upon coarse canvas, the whole of the ground being covered by the needlework.

Two strips (facing page 99), dating from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, quaintly depict, with the costume, architecture and other accessories of their period, two stories of the love and enmity of Venus, as enshrined in late classic mythology. The incest of Myrrha or Smyrna, with the connivance of her nurse, is followed by her metamorphosis, to enable her to escape her father’s vengeance, into a tree.

Next is portrayed Myrrha’s child, Adonis, grown up and hunting a boar, from which he receives a fatal wound; and lastly Venus, with her attendants, mourning for the death of Adonis.

Another example of petit point, all in silk, embellished by gold thread, is signed at the lower corners with the name, Mary Hulton (picture above). The initials J. R. and the royal arms, quarterly France modern and England, with Scotland in the sinister, and Ireland in the opposite dexter quarter, prove tha the work cannot have been finished earlier than the reign of James I.

The floral forms represented are partly conventionalized renderings of actual plants and partly abstract, all, however, growing indiscriminately from the same stem in the inorganic fashion that marks the initial stage of decadence.

From that treasure-house of embroideries, Hardwick Hall, is reproduced a set of four small panels, about 10 or 12 inches high, worked in outline of laid thread upon brownish-green velvet.

Read more: Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, England.

One bears the date 1590, and another the coronet and initials of the Countess of Shrewsbury, both within borders of strap ornament; while the others represent respectively the earth’s sphere and a pair of balances.

To the same place belong the two round stools and the back and seat from a chair of the suite in the Presence Chamber (picture above), the work of Jacobean or perhaps early Caroline date. The embroidery is executed firstly upon canvas and then cut out and applied to the velvet ground, which age has toned from the original crimson to a rich, purplish brown.

Among the floral forms may be recognized borage and poppies on the stools, and roses, daisies and strawberry blossoms, leaves and fruit upon the chairs. That the floral motifs do not suffice of themselves, but have to be supplemented by incoherent units like caterpillars and butterflies, betrays a certain limitation of the ornamental design of the times; and also how it was then already verging into the inconsequent type of the Caroline and Commonwealth periods, called embroidery “on the stump.”

Aymer Vallance.

Source:

- Art in England during the Elizabethan and Stuart Periods. Written by Aymer Vallance, Charles Holme, Malcolm Charles Salaman. London; New York: Offices of the Studio, 1908.

- A Book of old embroidery by Albert Frank Kendrick (1872-1954)and Charles Geoffrey Holme (1887-1954). London; New York: “The Studio”, 1921.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.