The citizens’ costume of the Romans. The Togatus and the Roman ladies of the imperial period. A horseman in battle.

Roman clothes.

The toga consisted of a single, about 6 meters long and 2½ meters wide, semi-circular piece of fabric, which was draped around the body without knots, ribbons, fibulae or other attachments. Wearing a toga allowed only measured movements so that the fabric would not slip. In order to achieve at least a certain safety against slipping, sometimes lead balls were sewn into the hem.

The term toga is derived from tegere (covering, dressing) and literally means covering, clothing. The origin of the toga is unknown. As gens togata, means Toga bearer or a person dressed a toga, the Roman felt in contrast to the Greek, the palliatus, the one dressed with the pallium. The toga was replaced in the war by the sagum or paludamentum, similar to the Greek chlamys.

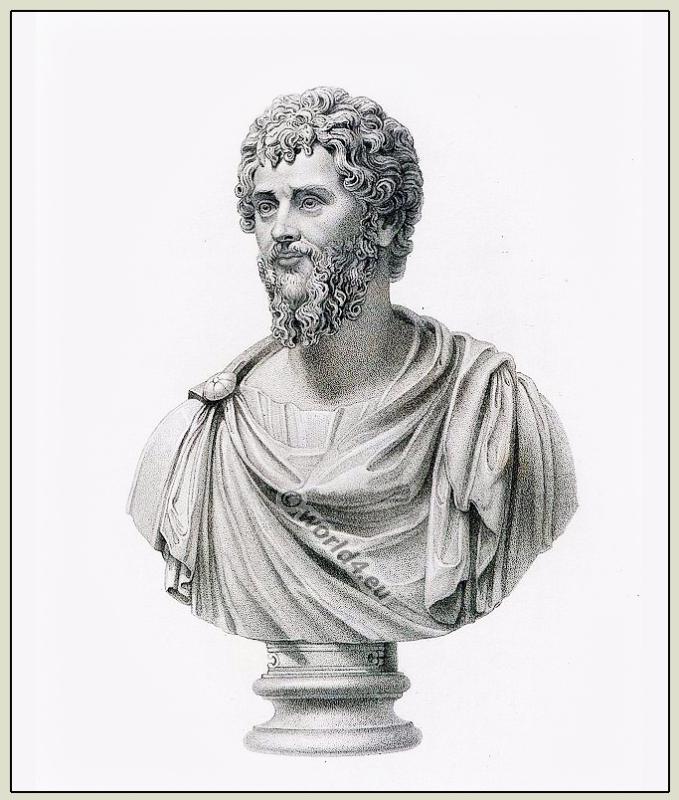

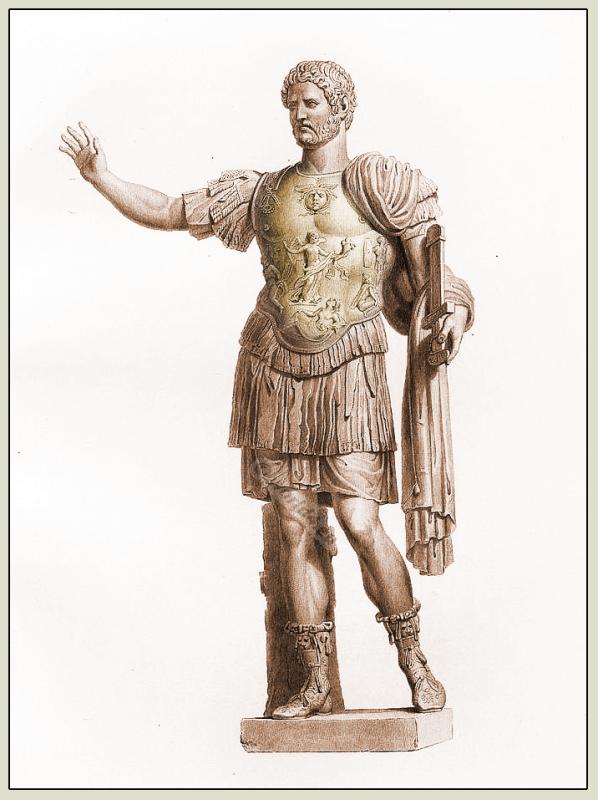

The paludamentum was the coat or cape of generals and soldiers. The coat consisted of a rectangular piece of cloth and was beaten over the left shoulder like the sagum of the Roman soldiers and fastened to the right shoulder with a brooch. It had less practical use, but rather served as an insignia of rank (depending on the colour of the coat). Roman emperors are often depicted with the paludamentum on coins and statues.

In the imperial period, a distinction was also made between the Togatus, the wealthy citizen, and the Tumicatus, who lived off his hands’ work. The toga of the preferred, higher estates was made of white wool, that of the craftsmen and poor of dark dyed wool. The stranger was not allowed to wear it at all; it remained the insignia of the free Roman citizen. The limed, purely white toga candida – hence the term “candidate” – was worn by applicants for public office.

The putting on of the toga happened in the following way. One end of the toga was placed over the left shoulder so that one third of the entire length covered the left side of the body and fell between the feet at the front, then the rest was pulled over the back, under the right arm at the back; the rest was placed twice, covering the lower body and falling over the left shoulder to the heels (see nos. 2 and 5). No. 5 also shows the double sine or bulge.

Velatus was the name given to the person who pulled the toga over the back of the head. It was a sign of the mourner or victim (cf. No. 13). The arrangement of the speaker’s toga is illustrated by nos. 5 and 10.

The higher magistrates (Curulan aedles, praetors, consuls, censors) as well as the members of the four great priestly colleges (Pontifices, augurs, epulons and Quindecimviri) in their official function wore a toga (toga praetexta) framed with a purple stripe about 75 millimetres wide, as did the boys until they reached adulthood. Then the young men took off the toga praetexta in a ceremony (tirocinium fori) and from then on as adults wore the simple, unbrushed toga, the toga virilis or toga pura.

The toga picta, a purple toga decorated with golden stars, or the toga palmata (trabea) decorated with embroidered palm branches of the triumphator became the official costume of the consuls and praetors during the imperial period.

The Toga rasa, made of light fabric, was intended for the summer; a transparent Togae vitreae was also worn.

The Clavus angustus (angusticlavia, angustiores clavi) was the badge of the knighthood and consisted of two narrow vertical purple stripes on the front of the tunic.

No. 3 shows the type of emperor with laurel wreath and purple toga; No. 4 is a picture of Nero as he appeared in the synthesina, a mixture of Greek and Roman costumes, after his return from Hellas.

No. 6 is a bronze statuette of Alexander the Great, which illustrates the Roman origin of the habitus of the fighting horseman.

The Roman ladies. The pallium or the palla.

In the early republic, rich women wore the toga just like men. In the 2nd century B.C. this type of clothing went out of fashion. At the time of Augustus at the latest, women rarely wore the toga, especially girls before puberty, in fact the toga worn by an adult woman was considered a sign of prostitution. The stole was the female counterpart to the toga. This dress was also often combined with a Palla worn over the shoulders. The stole was worn as a badge of social rank and was a sign that the woman was married. Compared to the toga, which was only made of white wool, the stole was made in all possible colours, including red, yellow and blue. Instead of linen and wool fabrics, which were used for men’s clothing, cotton and especially silk, which came from the Orient, were preferred.

The female clothing consisted mainly of tunica, stole and undergarments. On the skin, the women wore a shirt, the tunica interior, and under or above this shirt the strophium (various fabric and leather bands), which corresponds to today’s brassiere. Over the shirt they wore the stole, which represented the clothing of the Roman citizen, similar to the toga for the men.

The palla of the Roman ladies has nothing in common with that of the Greek ladies. In the first centuries of the republic (about 500 – 150 B.C.) the women wore the ricinium, a simple square cape covering the shoulders and sometimes also the head, as an overhang. In the last centuries of the republic (about 150 B.C. – 400 A.D.) and during the imperial period, this was replaced by the palla, a very wide and rich garment that had the shape of a cloak. It is a long, square-cut mantle worn by women, fastened by brooches, that goes down over the feet and was worn by women in the Roman Empire when they went out to dress over their other garments. It is the counterpart to the coat worn by the men, the pallium. Part of the traditional wedding attire was the yellow-red Palla galbeata.

No. 8 is a pudicitia, an allegory of shamelessness, of the museum in the Vatican. The palla is pulled over the back of the head, while a diadem rises above the forehead. The sandals have thick soles.

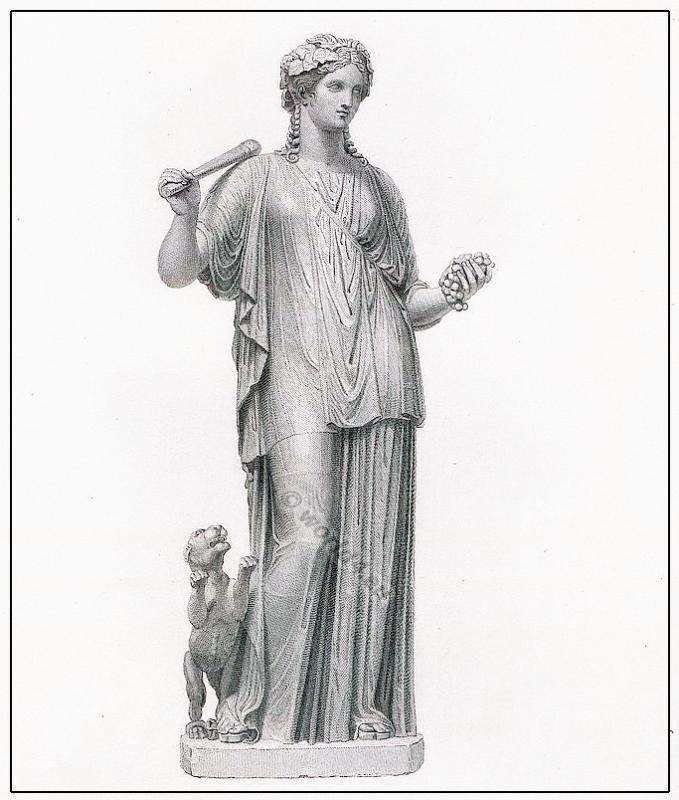

No. 9 is a calliope.

No. 12 represents a sibyl of the museum in Naples.

No. 7 depicts a statue in parish marble, formerly in the gardens of Marly, which uses the palla that surrounds the whole body at the same time to cover the lower part of the face.

No. 4 is a young noble lady after an antique of the Villa Medici.

No. 1 is reconstructed after a figure of the Aldobrandin wedding (Roman fresco painting from Augustan period 30 B.C. to 14 A.D.).

The originals of the male figures come from: No. 2 from Villa Medici, No. 5 from Villa Pamfili, No. 6 from the Museum in Naples, No. 10 from the Garden of Marly, No. 13 from the Museum in Naples. No. 11 is borrowed from the collection created by Levacher de Charnois and published in Paris in 1790.

Source:

- History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Editor: Firmin-Didot et cie. Paris, 1888.

- A description of the collection of ancient Marbles in the British Museum by Combe Taylor, London 1861.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.