Ralph Waldo Emerson Barton (August 14, 1891 – May 19, 1931) was an American artist, cartoonist, caricaturist, and filmmaker, decorated with the Légion d’honneur and companion of Germaine Tailleferre.

During the years 1910-1920, Barton managed to sketch most of the celebrities of his time. His last sketch was of Charlie Chaplin. One of his most famous drawings, “When the Five O’Clock Whistle Blows in Hollywood”, appeared in Vanity Fair in September 1921 and depicts 139 Hollywood celebrities in a sort of curtain-raising “revue” immortalised on Hollywood Boulevard. He also worked for The New Yorker from 1924, as an art adviser, and contributed to Collier’s Weekly, Judge and Harper’s Bazaar, in which Anita Loos’ comic novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was serialised from 1925.

At the insistence of his friend Chaplin, he made a single short film in 1926, Camille, a free adaptation of The Lady of the Camellias, starring, among others, Paul Robeson, Ethel Barrymore, and Sinclair Lewis, and featuring Paul Claudel, Sacha Guitry, etc., a very impressive cast of French, German and American artists of the time.

At the height of his popularity, admired and respected, Barton was in fact prone to acute forms of depression, probably suffering from manic-depressive disorder. After three successive divorces, he eventually married the French composer and musician Germaine Tailleferre. But Barton, jealous of his wife’s talent and fearful of the success she might have, opposed her musical career, making their marriage impossible and lasting only three years. In fact, he was unable to recover from his separation in 1926 from his third wife, the actress and director Carlotta Monterey.

On 19 May 1931, in his Manhattan flat, he ended his life by shooting himself in the temple. Barton was forgotten relatively quickly. In 1968, the Rhode Island School of Design organised an exhibition of his drawings. In 1998, the National Portrait Gallery (Washington D.C.), which owns a Barton collection, and the Library of Congress paid him a major tribute.

RALPH BARTON

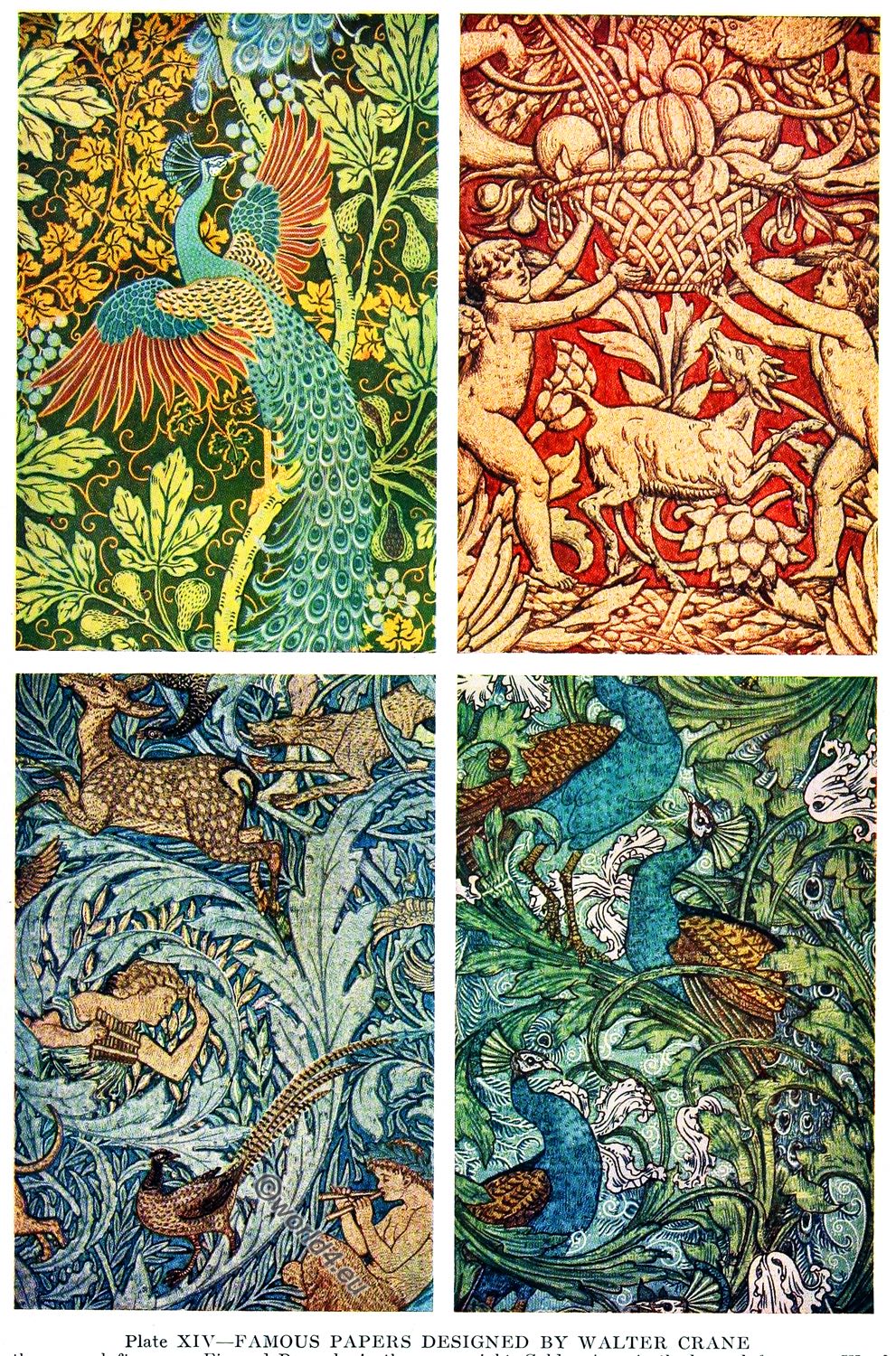

GENERALLY an artist can be placed within the limits of a certain school or its suburbs, but we defy any art historian to place Mr. Barton in any one section of art’s vertical file. Nor could we blame the baffled “clerk of the collection,” who, as Whistler wrote, loves to “mix memoranda with ambition and reducing art to statistics, files the fifteenth century and pigeon-holes the antique.”

The fault is Mr. Barton’s. By his own words, he is as conglomerate as the Tower of Babel. “I hail from the state of Missouri, and am about as American as it is possible to be, both sides of my family having quit England for these shores before the English were obliged to quit them, and being myself the possessor of enough Cherokee blood (one-sixteenth) to make me adore the scale of primary colors. Everybody m America thinks my work is ‘French.’ In France they thought it was ‘un peu boche!’ and in Germany I suppose they would call it Chinese. As a matter of fact, I copied the designs on Greek vases at first and developed the style from that.”

He is Middle-Western, English, American Indian, “a little bit German, French, Chinese and Greek, and to crown it all lives in Babylon—Long Island.

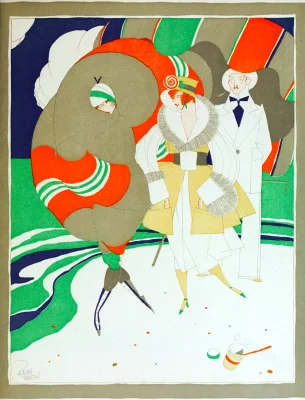

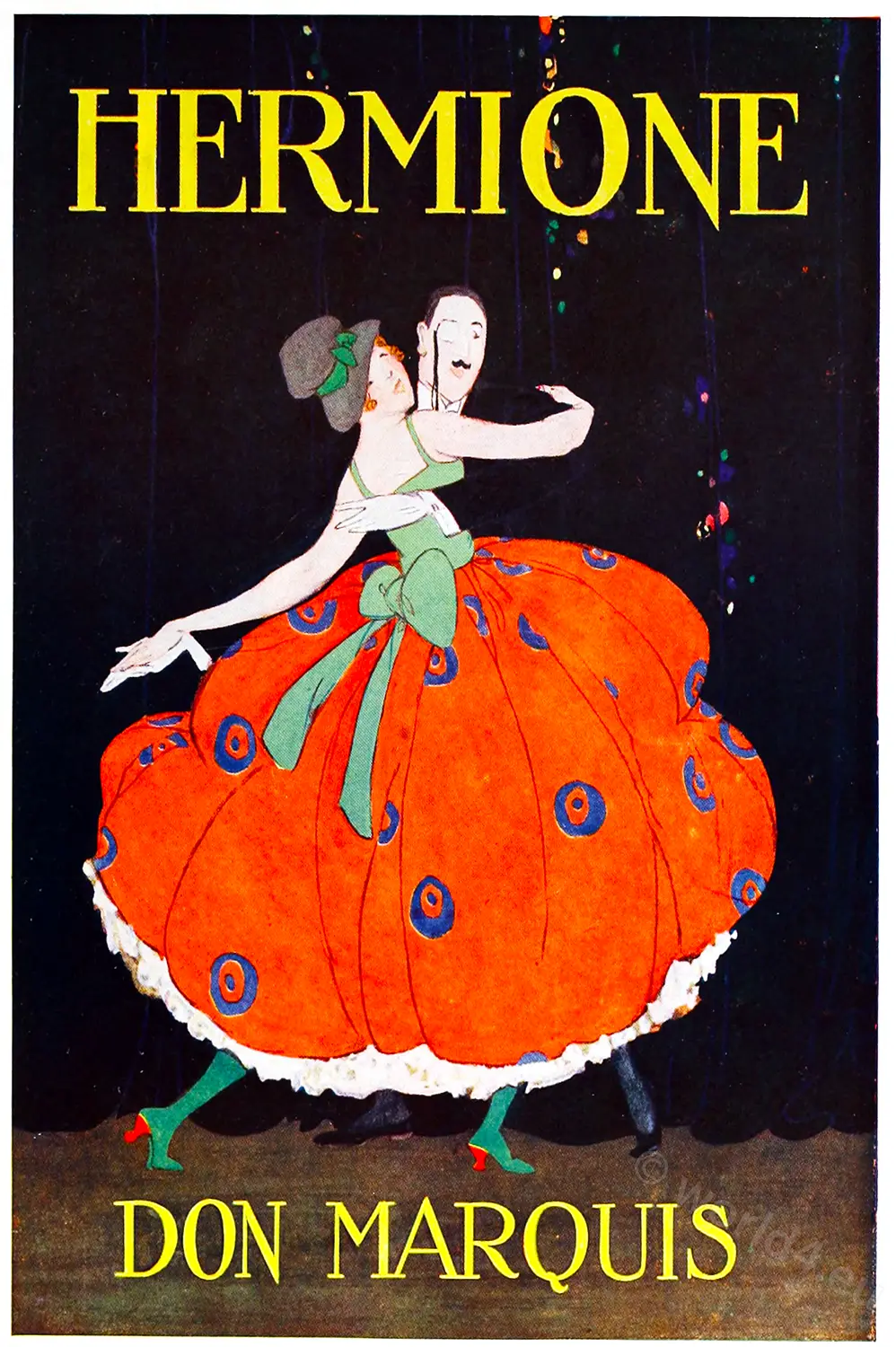

Our exhibit is an excellent example of his love for pure color in curious, modernist masses. The initial on this page, done especially for this book, is very “amusing,” to borrow a bit of studio slang. He has worked for a great many firms and a great many kinds of firms—advertising companies and humorous weeklies in particular — and Puck more than any other of the humorous papers.

Source: Some examples of the work of American designers by Dill & Collins Co; Joseph Moore Bowles (1865-1934). Philadelphia : Dill & Collins Co. 1918.