GRECO-ROMAN.

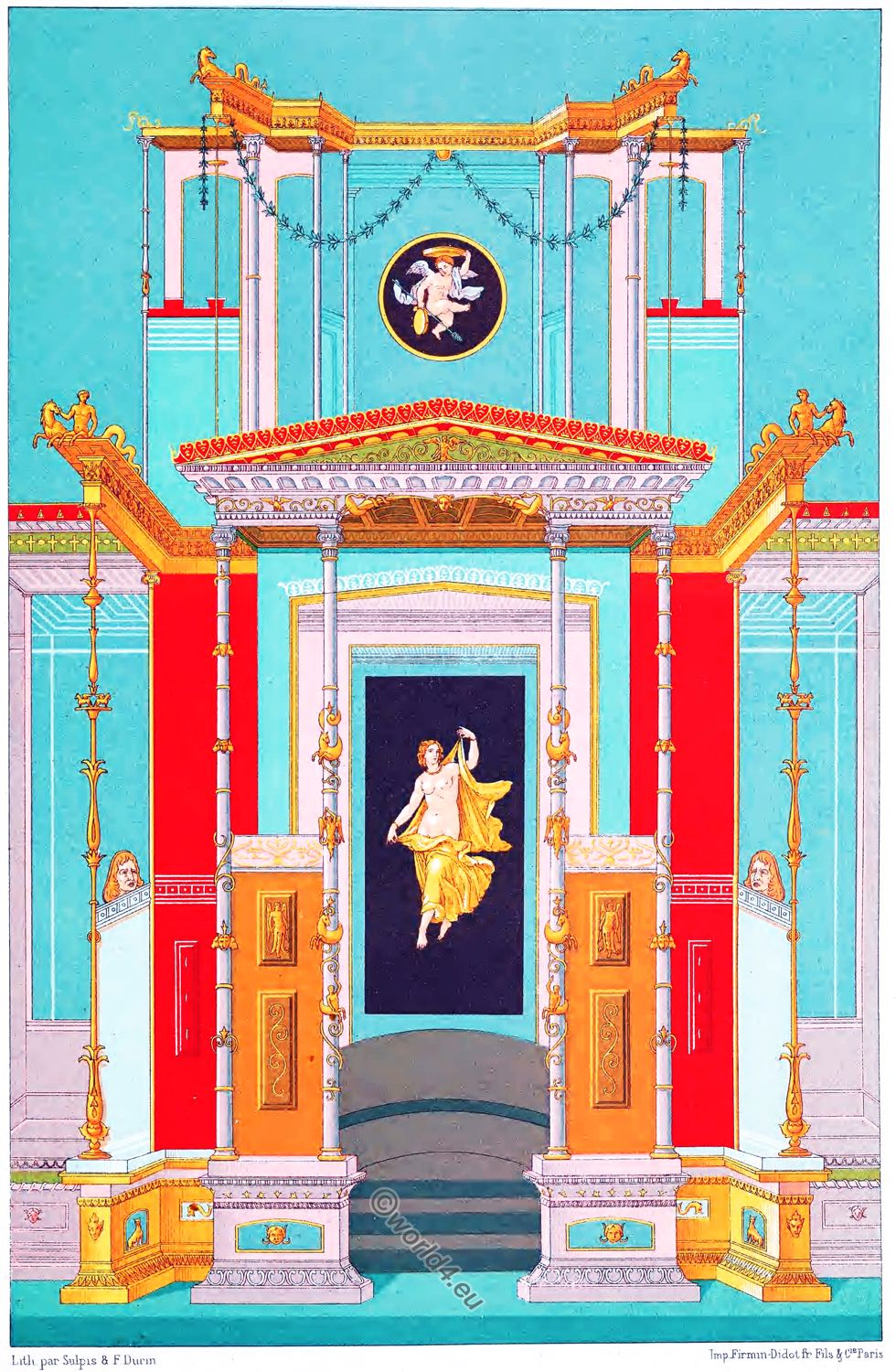

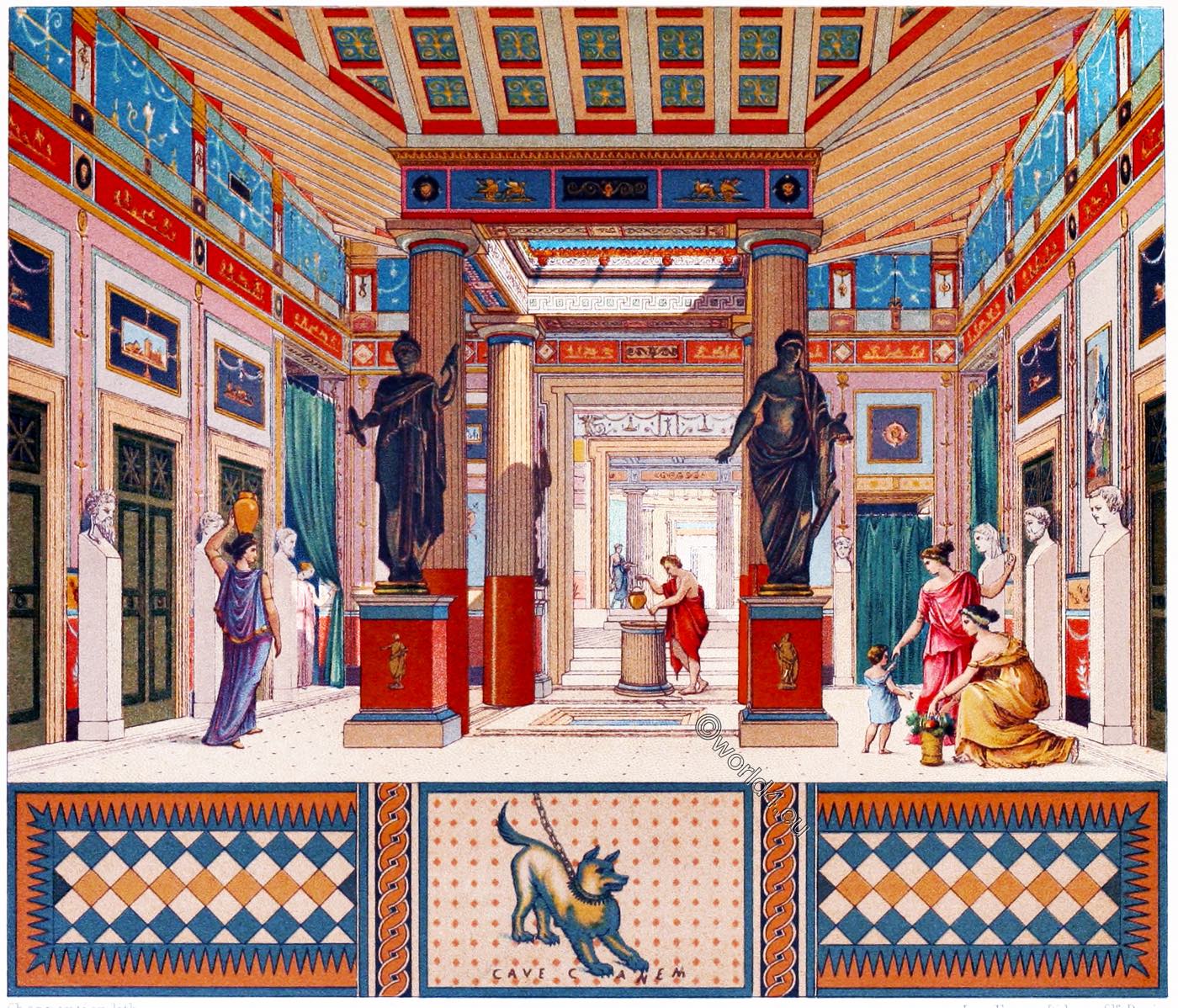

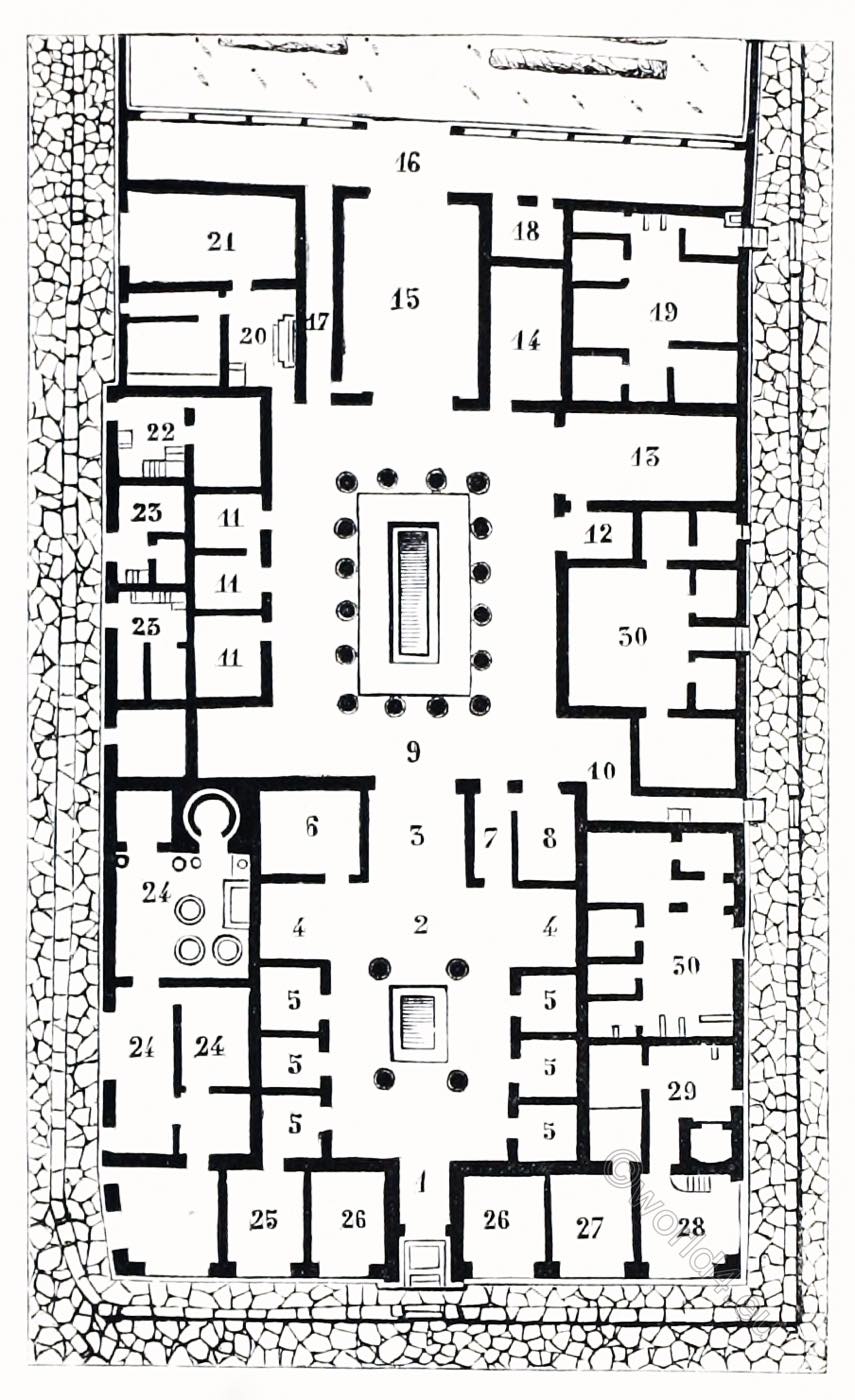

THE POMPEIAN HOUSE. THE ATRIUM. (RESTORATION BY JULES BOUCHET) PLAN AND SECTION OF THE HOUSE OF THE PANSA.

The Roman House almost always has the same floor plan; differences only arise in the size, number and distribution of rooms. The two main parts are always the atrium or cavaedium, the vestibule for external communication, and the peristyle (Latin peristylium), corresponding to the gynaeconitis (female tract, Latin gynaeceum or gynoeceum) of the Greeks, for internal life. The tablinum, open on both sides, forms the middle phalanx or central part.

The Pompeian House usually combined the character of the private dwelling with that of the apartment house. In this commercial city, people sought to earn a certain amount of interest on their property, hence the principle of the tavernae open to the street, which were rented to small merchants, and the chambers above, which were given to Inquilini (tenant). Naturally, the owner’s private home was extremely constricted by this system.

The tavernae were mostly thermopoleis, better wine taverns for hot drinks, oenopoleis, smaller pubs, or popinae, cookshops. They all had no access to the inside of the house; unless the owner himself was the owner of such a shop.

The facade was kept extraordinarily simple. Built up in two, rarely three floors, it showed only a few openings in the upper floors or a few covered galleries. The flat roof formed the solarium, a kind of terrace, to which one tried to give shade by stretched out velaria *).

*) A velarium (“curtain”) was a type of awning used in Roman times. The main function of the velarium was to create a ventilation updraft that provided air circulation and a cool breeze.

Lava, tuff, peperine, travertine and marble were used as building materials. Painted stucco was used everywhere with special preference. The best type of Greco-Roman dwelling, as it most suited the Pompeian taste, is the house of Panza, excavated between 1811 and 1814.

The quarter formed by this one house had its main front facing the street of Fortuna. There were six Boutiques (shops) here, one of which (no. 25) is connected to the interior, while only one narrow entrance (no. 1) remains free.

No. 1 – Ostium or Prothyrum. The prothyrum, the vestibule of the Roman house, is here a narrow corridor which served as a stay for the Ostiarius, the doorkeeper. The chamber of the latter was probably located to the right behind the prothyrum.

No. 2. Atrium. You can get into the same directly through the ostium. It was a covered courtyard with an opening for air and light in the middle of the roof, which corresponded to a basin for collecting rainwater. The atrium in the House of Panza (No. 2) is, according to Bouchet’s restoration, a tetrastylum with a roof sloping towards the centre and supported by four columns. It originally served as a family meeting room until the intimate life withdrew into the peristyle. The tablinum (No. 3) belongs more to the atrium than to the peristyle.

At the beginning it contained the family archive, later it was used as a dining room and it could be closed by curtains. If one wanted to avoid passing through this room, one went through the narrow corridor (No. 7) from the atrium to the peristyle. (No. 17 also serves as a passage from the peristyle to the garden). The chamber (No. 8) is called the abode of the atriensis *), the slave to whom the special supervision of the atrium was entrusted.

*) The steward who ran the whole economy.

No. 6 was the library; No. 4 were reception rooms (alae) for visitors and clients. The other rooms grouped around the atrium (No. 5) served as guest rooms and as chambers for the slaves. No. 10 is a side exit facing the street.

No. 3. – Peristylium.

The peristylium was an open rectangular courtyard surrounded on all sides by continuous porticoes with flower beds, a fountain and a rainwater basin.

The basin, the Piscnia, in the house of the Pansa is about 2 m deep and was painted on the inside. In the middle there is a kind of pedestal (pedestal). The chambers (no. 11) were the bedrooms of the family. No. 13 contains the triclinium and no. 12 served as a serving room.

No. 15 – Oecus or Cyzicenian Hall (from Cyzicos, an ancient city in Mysia).

This representative room, borrowed from the Greek house, was used to receive guests and as a banqueting hall for the summer. In front of it, after the garden, there is a portico (no. 16) to which the special passage (no. 17) leads. No. 14 is the Lararium or Sacrarium, the chapel of the household gods, and no. 18 is a kind of boudoir where one held one’s siesta. No. 21 serves as a place of residence for the slaves and therefore has a special connection with the road. No. 20 contains the kitchen and the adjoining rooms, the Horreum, the Olearium, the Cellae vinariae and the Carnarium.

Nos. 22 – 29 are the above-mentioned boutiques, of which nos. 22 and 23 contain special staircases to the dealer’s private residence.

Nos. 19 and 30 are separately rented accommodation.

Everywhere in Pompeii, even in the smallest houses, a kind of mosaic made of grey lava and marble, embedded in a mortar similar to red granite (Opus signinum), served as a barrel floor. By adding other coloured stones all kinds of ornaments, arabesques and figures were created. As far as the decoration of the wall surfaces is concerned, the base was kept dark, the frieze light, and the central surfaces in vivid colours, red or yellow. The plinth and frieze were initially covered with linear ornaments, then with arabesques and festoons. The wall surfaces were decorated with directly applied or embedded paintings.

The floor plan of the House of Panza by the architect Paul Benard.

The restoration of the average according to Léveil.

The restoration of the atrium according to Jules Bouchet.

The mosaic of the floor with the cave canem is in the so-called House of Homer.

Watercolor by the architect Hoffbauer.

Compare: Ch. Fr. Masois, Les Ruines de Pompéi, Paris, 1812-1838. – Derselbe, La Maison de Scaurus. – Faust und Fel. Nicolini, Le Case ed i monumenti di Pompei, Neapel, 1854. Raoul-Rochette, Peintures antiques inédites, Paris, 1836. Roux aîné und Barré, Herculanum et Pompei, Paris, 1837-1840. J. Gailhabaud, Monuments anciens et modernes, 1850. – Överbeck, Pompeji in seinen Gebäuden, Altertümern und Kunstwerken, Leipzig, 1884. Restored average of the House of Panza. after Léveil. From the “Monuments anciens et modernes” by Gailhabaud.

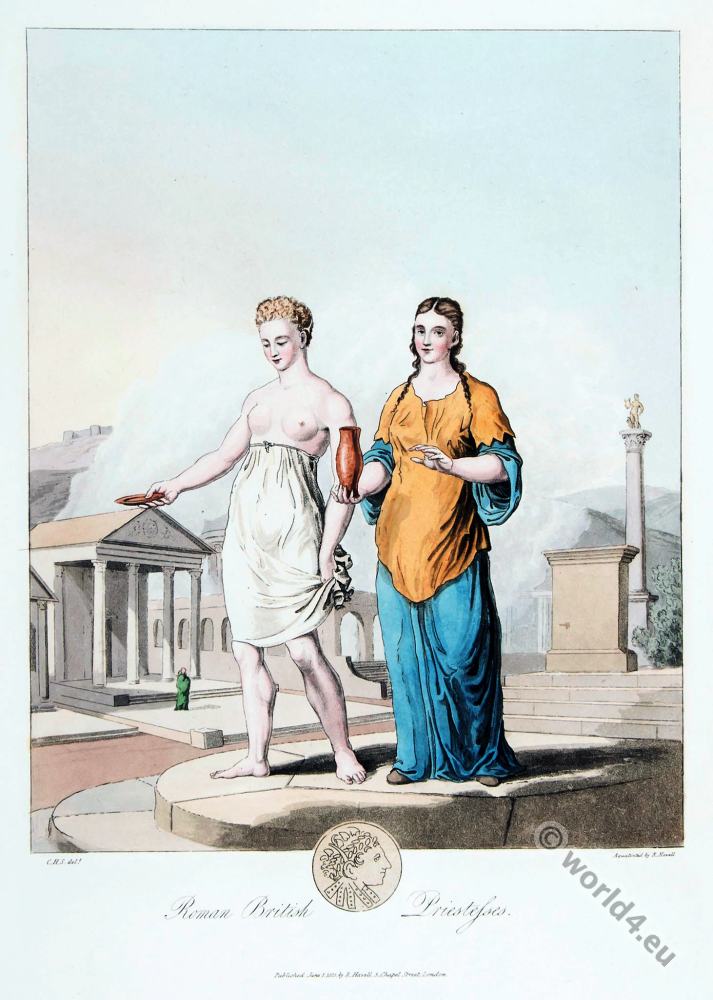

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Published by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Continuing

- Roman Costume and Fashion History.

- Roman clothing in its diversity and development.

- The early toga. Former roman clothing. 700 BC. – 500 BC.

- The Toga and the manner of wearing it.

- The costume of the Roman women. Republican Rome.

- The usual Roman garment during the Republican Rome.

- Roman Republic. Senator in the toga. A commoner in the paenula.

- The Togatus and the Roman ladies of the imperial period.

- The Roman Tunica or the Dorian and the Ionian chiton.

- Musical instruments. Wind and Stringed instruments of ancient Rome.

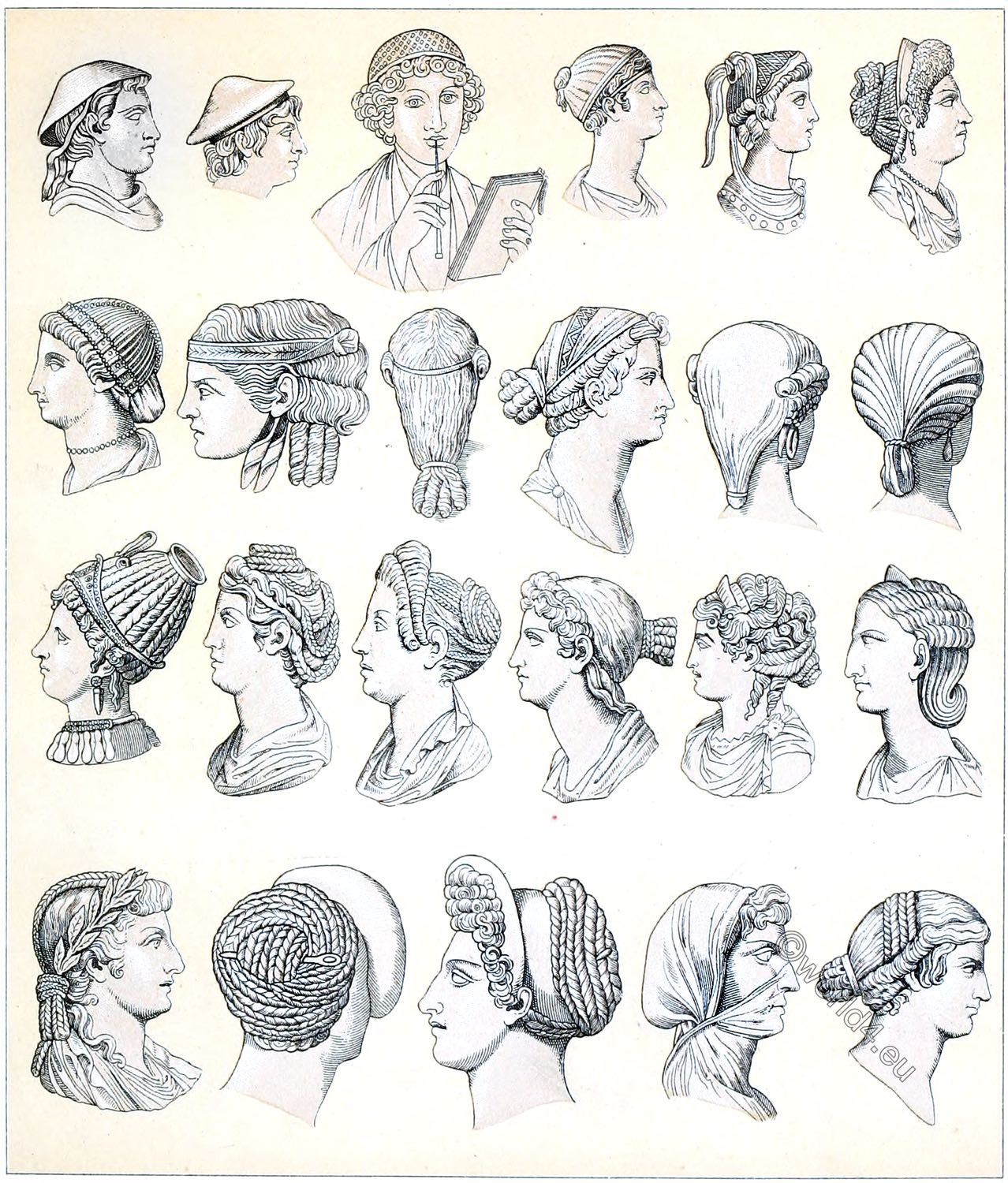

- Roman headgear and hairdos of antiquity.

- The Roman army. The legionary soldier. Equipment, assault weapons.

- Roman soldiers and gladiators. Function, armor and armament.

- The Roman legionary. Reconstructed after reliefs of the Trajan’s Column.

- The Lictor panel. A stately Roman lictor in a rich costume.

- The Roman Paenula. The cowl or hood. Traveling cloak.

- Pontifex Maximus. Roman high priest of antiquity. Collegium Pontificum.

- An Augur. Roman official priesthood.

- Religious sacrificial ceremonies of Romans in ancient times.

- The Clothing of the Vestal Virgins. The Cult of Vesta in ancient Rome.

- Shoes of antiquity. Sandals, closed footwear of the ancient world.

- The Etruscans. Culture, costumes, warriors in Etruria.

- Greek-Roman furniture. Throne chair, Bisellium, Sella castrensis.

- Greek-Roman art. Mosaics, painted bas-reliefs and wall paintings.

- A quadriga. Greek-Roman Gods. The ancient greek-roman culture.

- The Roman Ornament. Corinthian and Composite Capitals. The Acanthus.

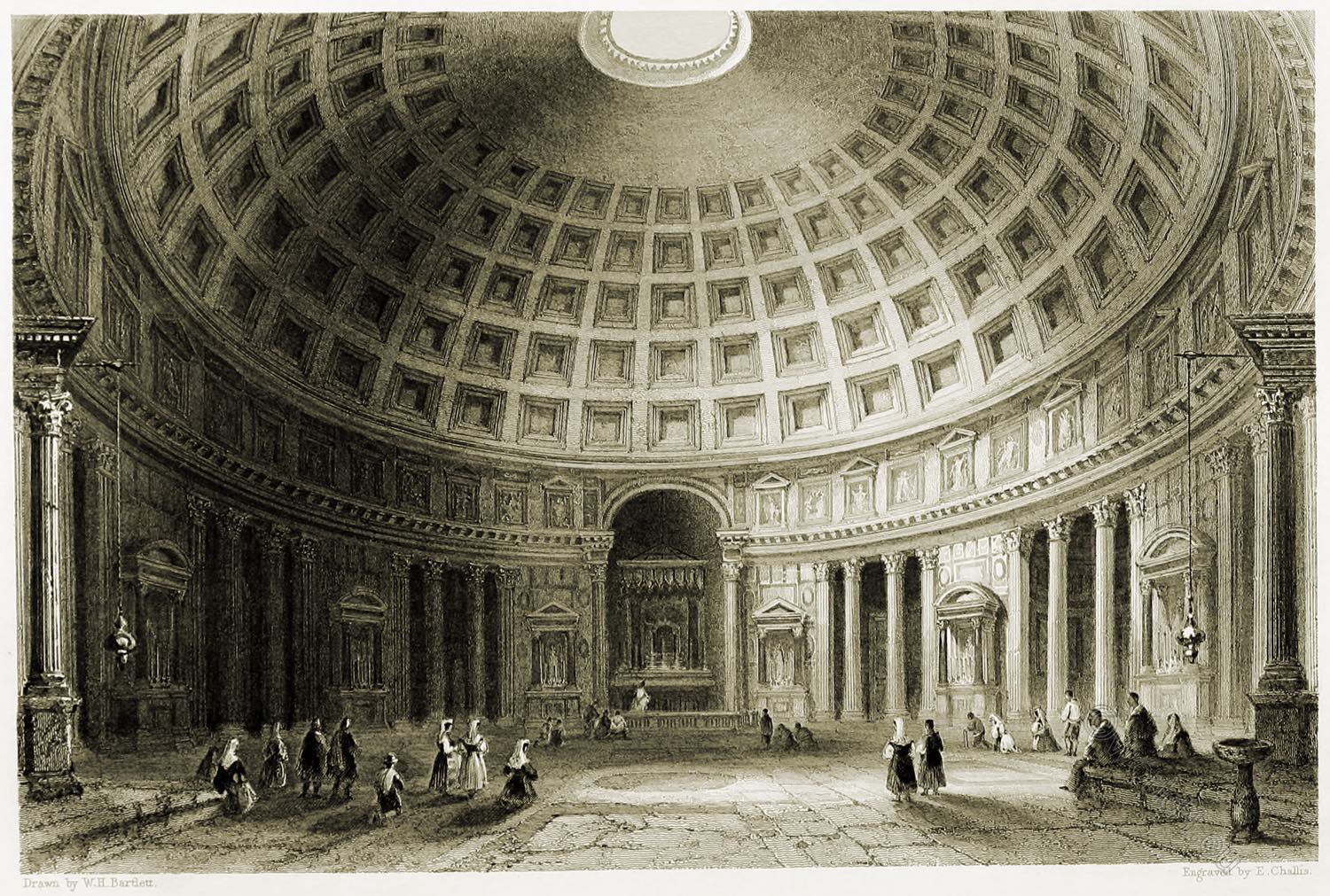

- Rome. The atrium. Interior of an ancient Roman palace.

- Pompeji. Roman architecture. The Pompeian House. The Atrium.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.