India. The Mughal Empire 1526 to 1858.

The Mughal Empire was a state existing on the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1858. The heartland of the empire was located in the northern Indian Indus-Gangetic plains around the cities of Delhi, Agra and Lahore. At the height of its power in the 17th century, the Mughal Empire covered almost the entire subcontinent and parts of today’s Afghanistan. The Mughal Empire was known for his tolerance of other religions and had a much higher standard of living than Europe at that time.

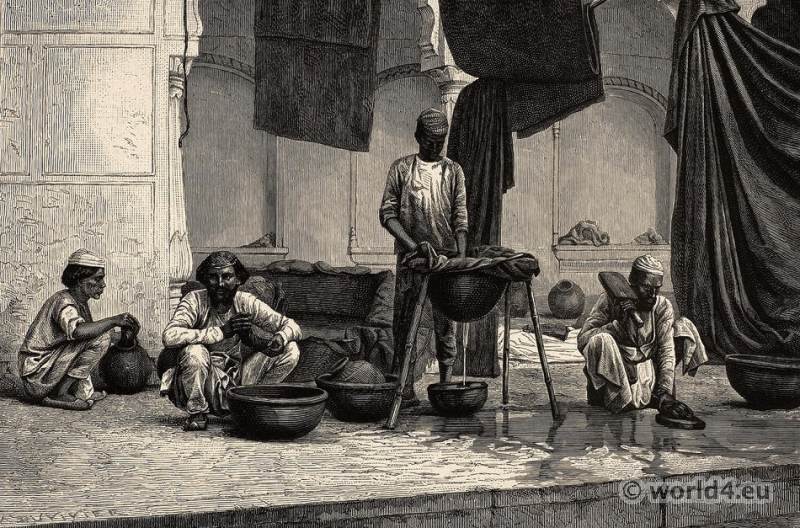

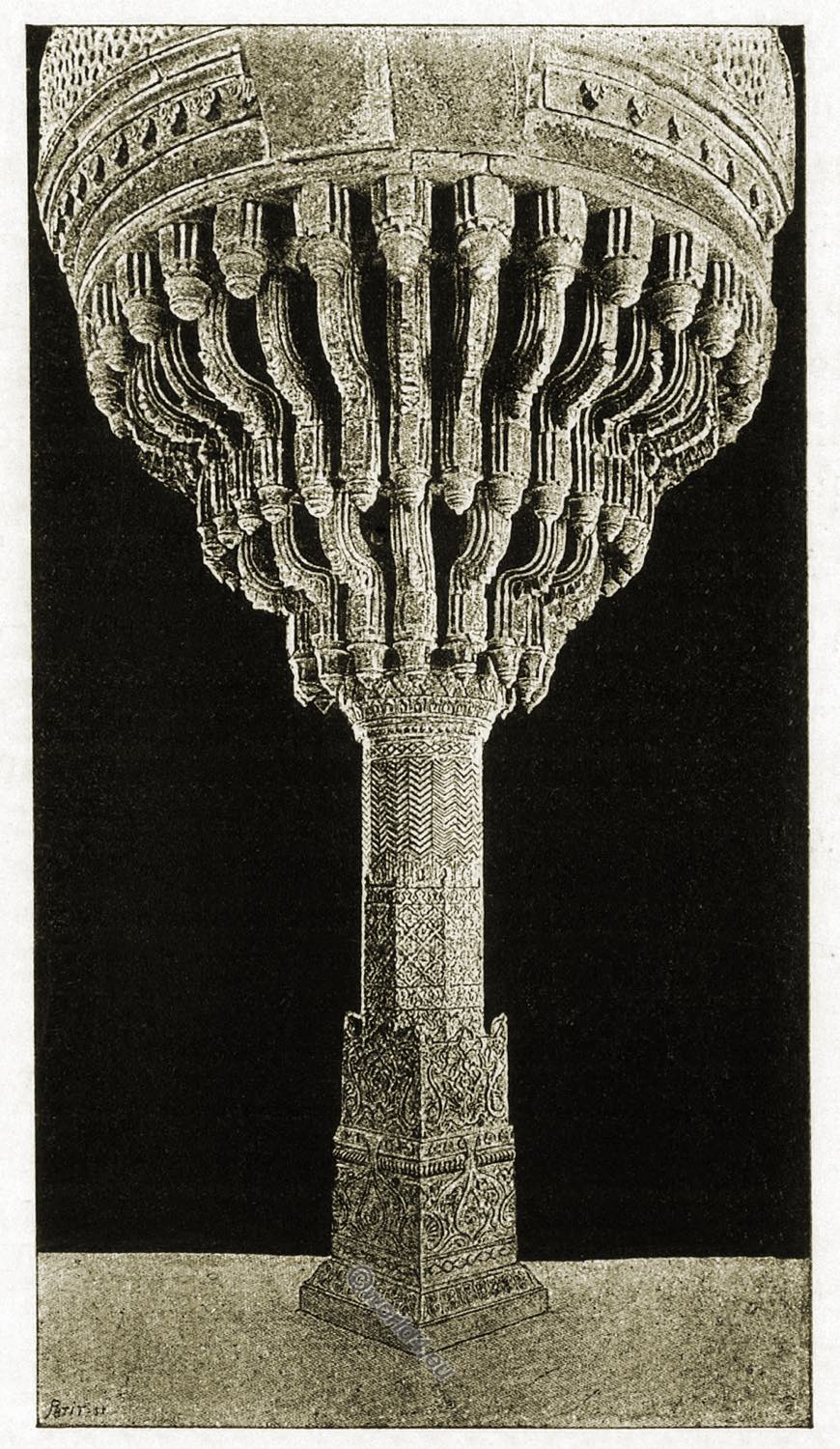

Salle D’Audience du Palais des Rois Mogols a Delhi.

D’après une photographie du Dr. Gustave Le Bon.

Audience Hall of the Palace of the Mogul Kings in Delhi.

Based on a photograph by Dr. Gustave Le Bon.

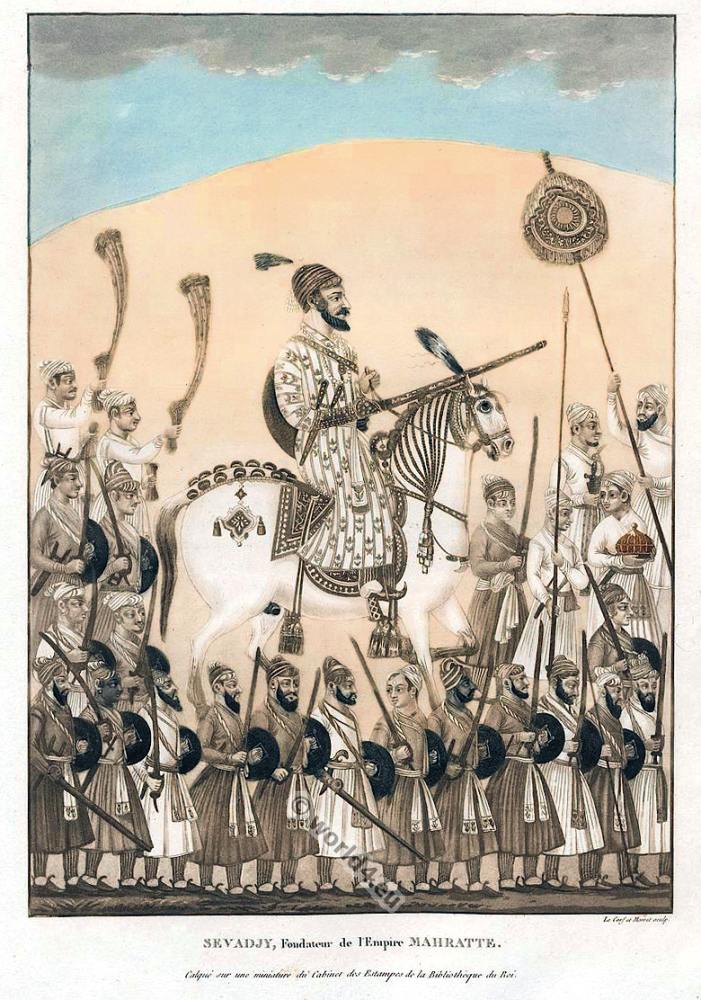

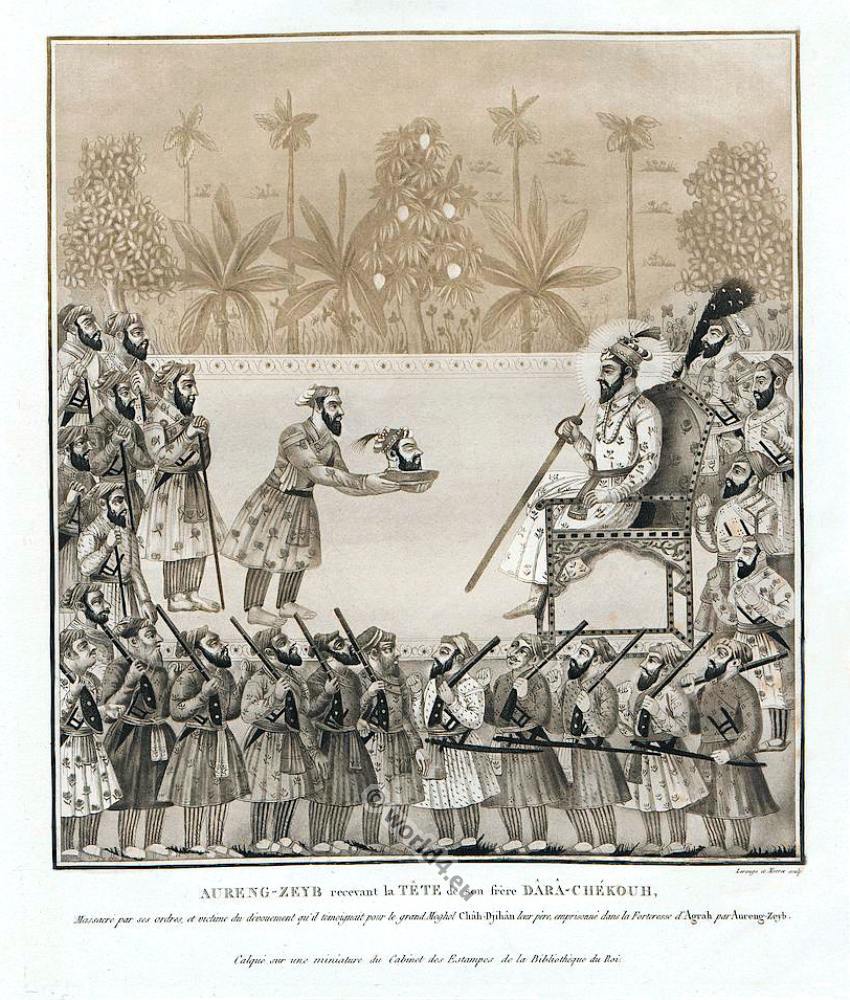

Under Aurangzeb (ruled 1658-1707) the Mughal Empire experienced its greatest territorial expansion. However, the territorial expansion overstretched it financially and militarily to such an extent that in the course of the 18th century it fell to a regional power in the political structure of India. Several serious military defeats against the Maraths, Persians and Afghans as well as the intensification of religious antagonisms within the country between the Muslim “rulers’ caste” and the subjugated majority population of peasant Hindus further favoured his decline. In 1858 the last Grand Mogul of Delhi was deposed by the British. His territory merged into British India. Rich evidence of architecture, painting and poetry influenced by Persian and Indian artists has been preserved for posterity.

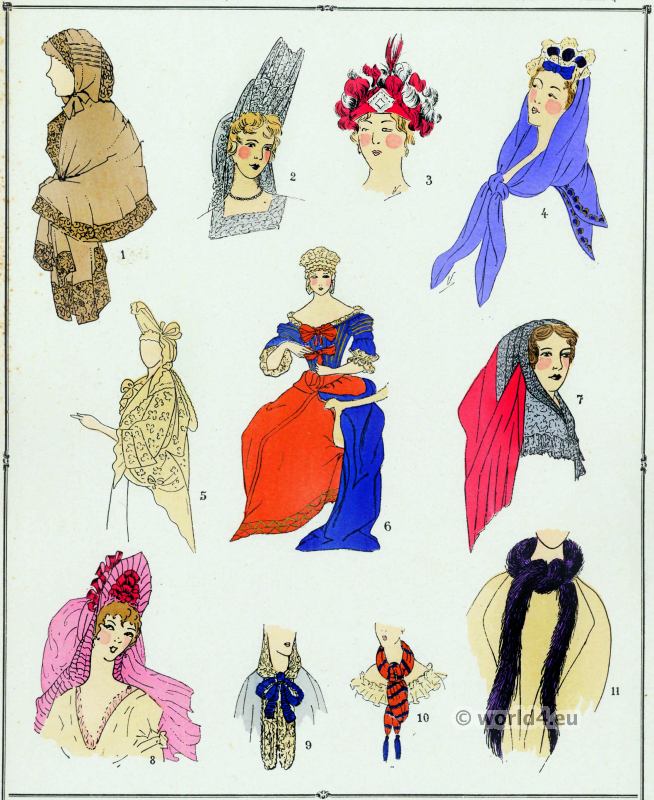

The people of ancient India had a philosophical outlook towards their clothes; these mattered little in life. But they were passionately fond of ornaments. The Muslim rulers loved both the glamour of garments and the glitter of gold. But as it was, not an inch of bare skin was available except on the face and the hands, for ornamental exhibition. The disadvantage was fully compensated by bejeweling dresses and wearing ornaments over them.

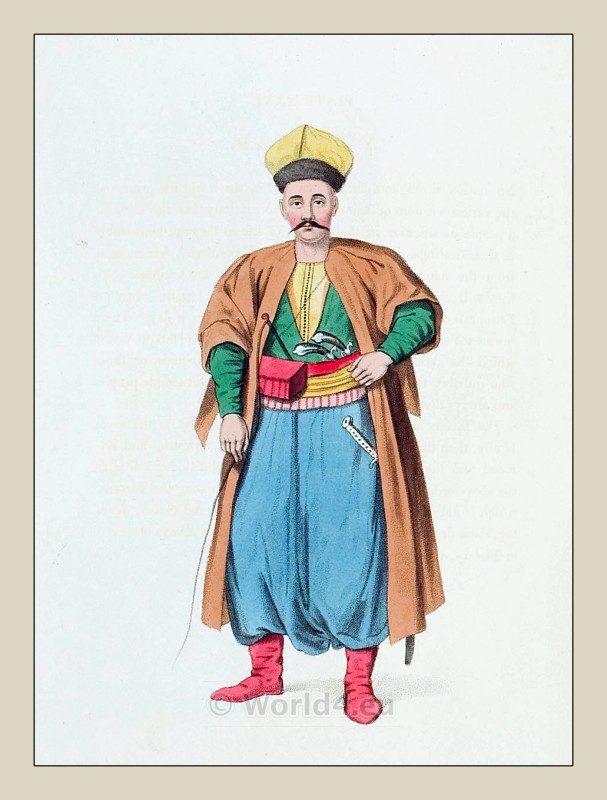

Ibn Batuta ( Abū ʿAbdallāh Muhammad Ibn Battūta 1304 – 1368 or 1369) at one place refers to a silk robe of blue colour embroidered with gold and studded with precious stones’ and ‘the precious stones were so many that the colour of the cloth was hidden from view’. The dresses of kings and nobles were a copy of Persian and Turkish fashions. In an account of the Muslim costume of the fourteenth century it is found that the Sultans, Maliks and other officers wore gown (jakalwat), coat (quaba) tied at the middle of the body and turban. The gown and sleeves were gold embroidered. They plaited their hair and put silk tassels on the hanging locks. They wore gold and silver belts and used shoes and spurs. Their turban was formed by putting a conical cap (kulah) on the head and winding a long piece of cloth round it.

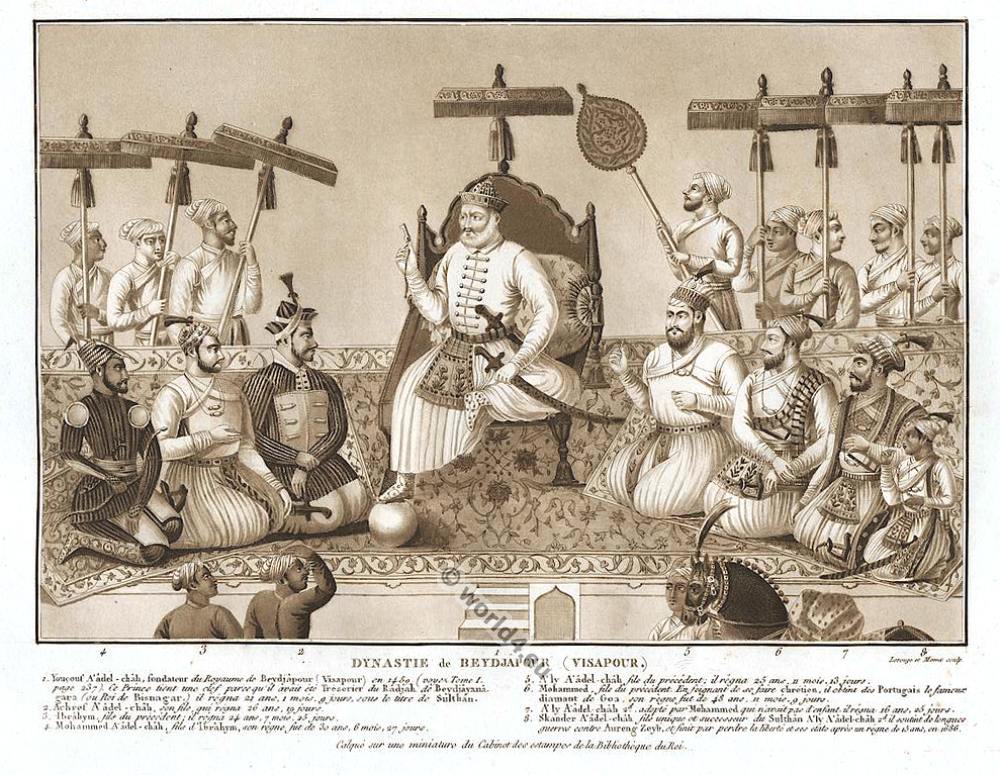

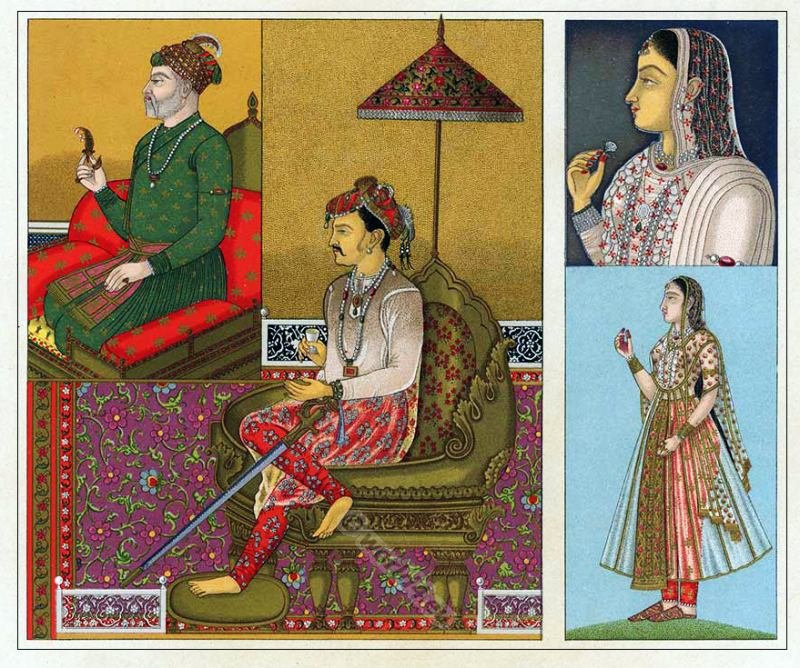

Picture above: The Grand Mogul and his court. This reproduction of an Indian miniature represents a Grand Mogul sitting on a throne. The miniature dates from the 17th century. These thrones were of elaborate ornamentation and raised admiration wherever they appeared. The main motif of the ornamentation here is a peacock. Similar elaborate thrones were mounted on horses and elephants. Two persons on the left represent the officials of the royal court. It is not clear, what was the function of the person sitting on the hexagonal chair, most likely it was Himad-oud-Deulet, the prime minister.

Fashion and foppishness had remained the pleasure and privilege of those who had pelf and power, culture and courage to accept the challenge of a change. During the Sultanate the difference between the well-to-do classes and the masses was almost antipodal. In spite of the political revolution, the villagers clad in scanty dresses remained busy with their ordinary occupation of life untouched and unmoved by any outside influence. When Babar entered India he found the dress of the masses so outlandish that he thought it important to be recorded in his memoirs in 1519. “Their peasant and lower classes,” he wrote, “go about naked.

They tie on a thing which they call langoti, which is a piece of cloth that hangs down two spans from the navel as a cover to their nakedness. Below this pendant modesty-clout is another slip of cloth one end of which they fasten before to a string that ties on the langoti and then passing the slip of cloth between the two legs bring it up and fix it to the string of the langoti behind. The women too have a lang, one end of which they tie about their waist and the other they throw over their head”.

The first Grand Mogul Babur (Zahir ad-Din Muhammad Babur. 1526-1530), a prince of the Timurid Dynasty originating from Central Asia, conquered the Sultanate of Delhi, starting from the territory of today’s Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

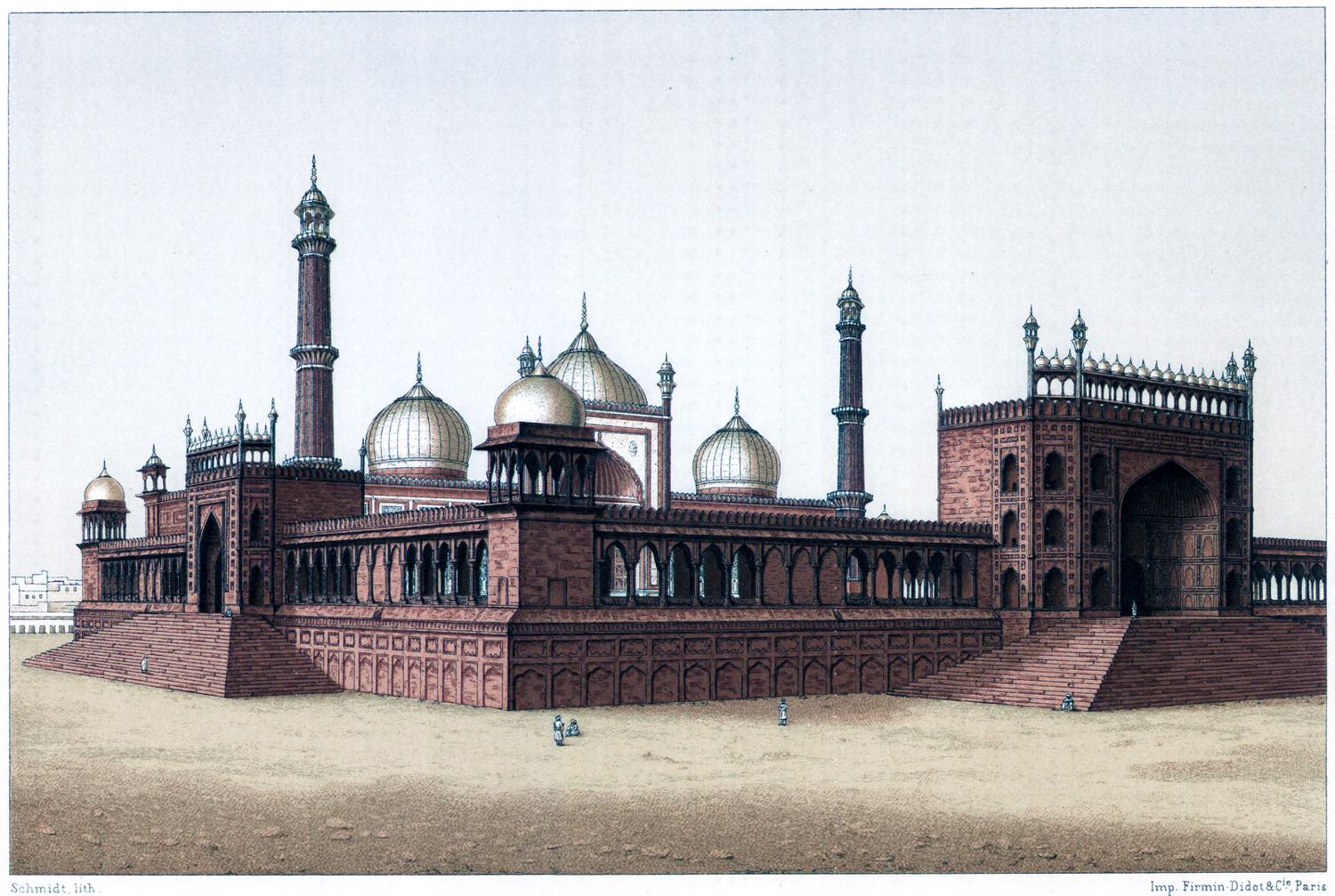

Grande Mosquée de Delhi. D’après une photographie et une aquarelle du Dr. Gustave Le Bon.

Great Mosque of Delhi.Based on a photograph and watercolour by Dr. Gustave Le Bon.

Babur himself used to put on clothes in many colour combinations. Over a tight- fitting long-sleeved garment, he wore a knee-length coat whose sleeves reached half way to the elbows. At the waist a kamarband was tied whose two gold tipped ends hung from a looped knot on the left. The short lapel of the coat, almost like a wide collar, was sometimes made of gold cloth. His turban was shaped by a long cloth, sometimes a gold cloth, wound several times round a tall kulah (a sort of pointed scull-cap). He wore close- fitting trousers with boat-like shoes. High boots up to the knees were worn while riding.

The outfit was suited for the cold climate of Central Asia from where it was imported. Babur’s attendants also wore a halfsleeved coat whose rear reached up to the back of the knees. At the front the coat displayed one, two or three short pointed flaps hanging from the waist.

Babur’s attire was more akin to that of a general and was appropriate to his great personality. With his indomitable spirit and remarkable military prowess he remained busy fighting the first battles that would lay the foundation stone of the Mughal Empire and open the way for an imperial line. Babur and Humayun did not have time or opportunity to think of any sartorial reform. The costumes of the days of the Sultanate continued.

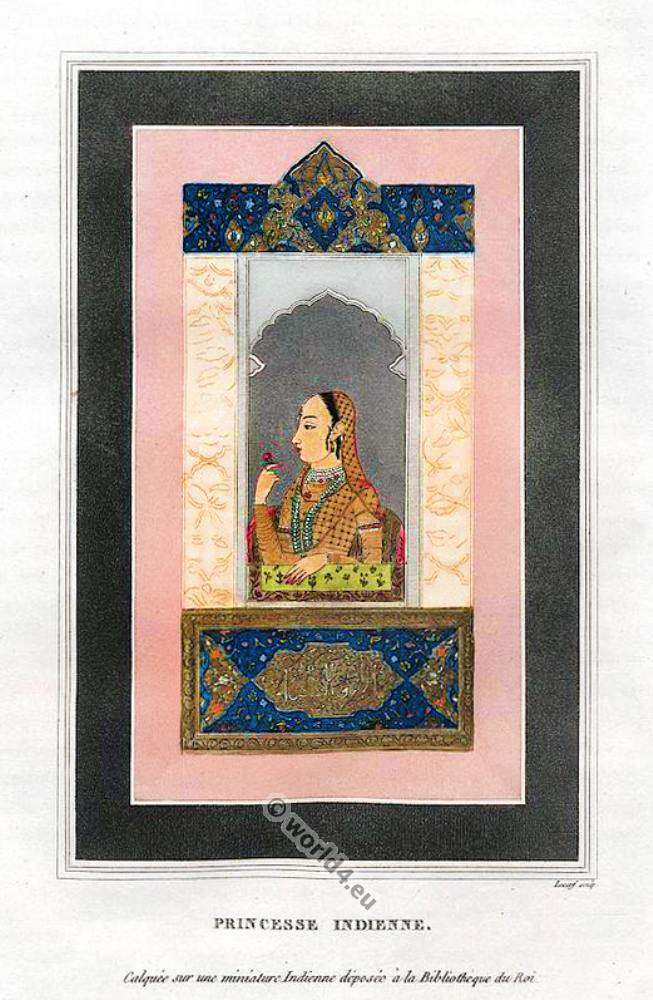

Mughal Princess Roshnara Begum (1617 – 1671), second daughter of Shah Jahan and Empress consort Mumtaz Mahal.

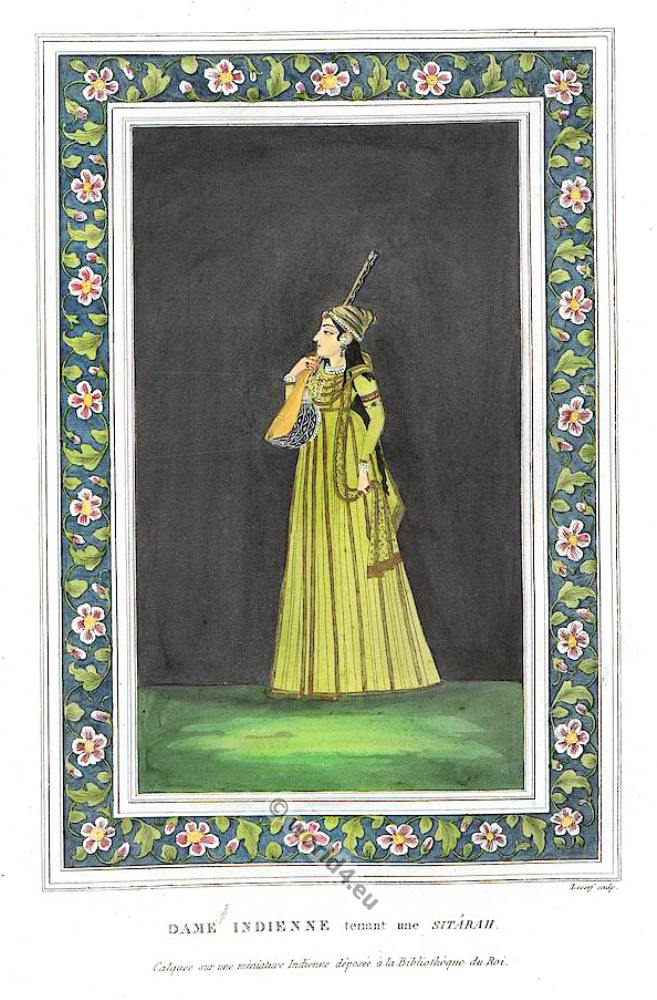

Shahzadi Jahanara Begum Sahib (1614 – 1681).

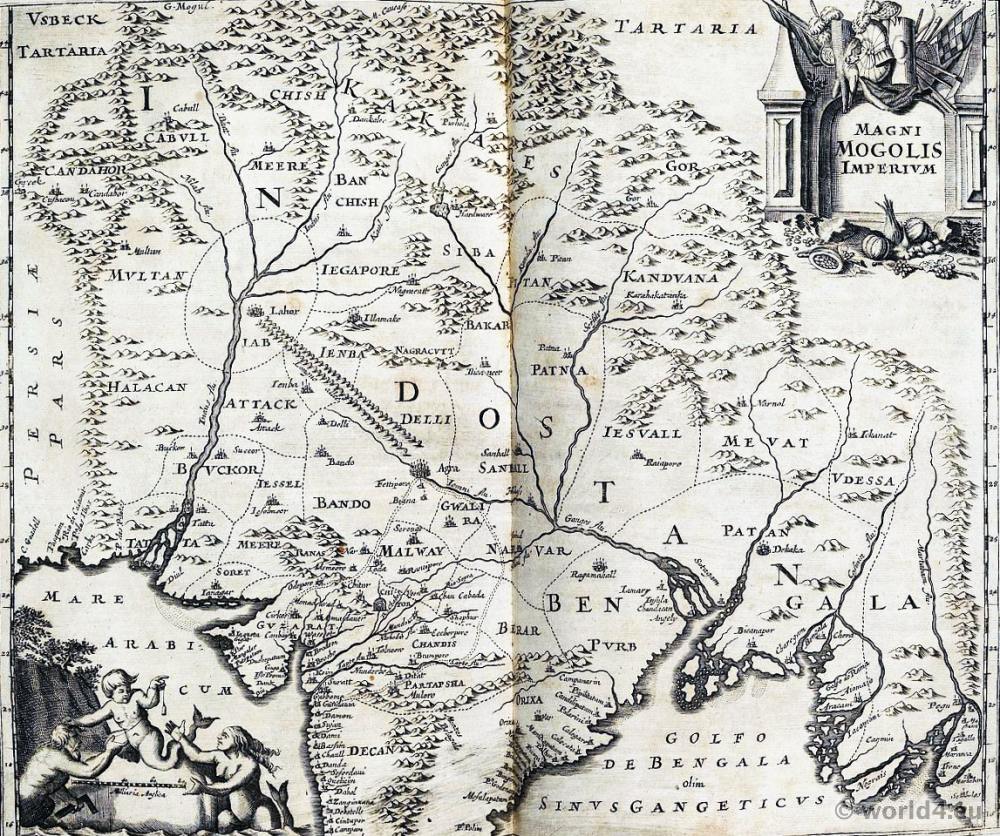

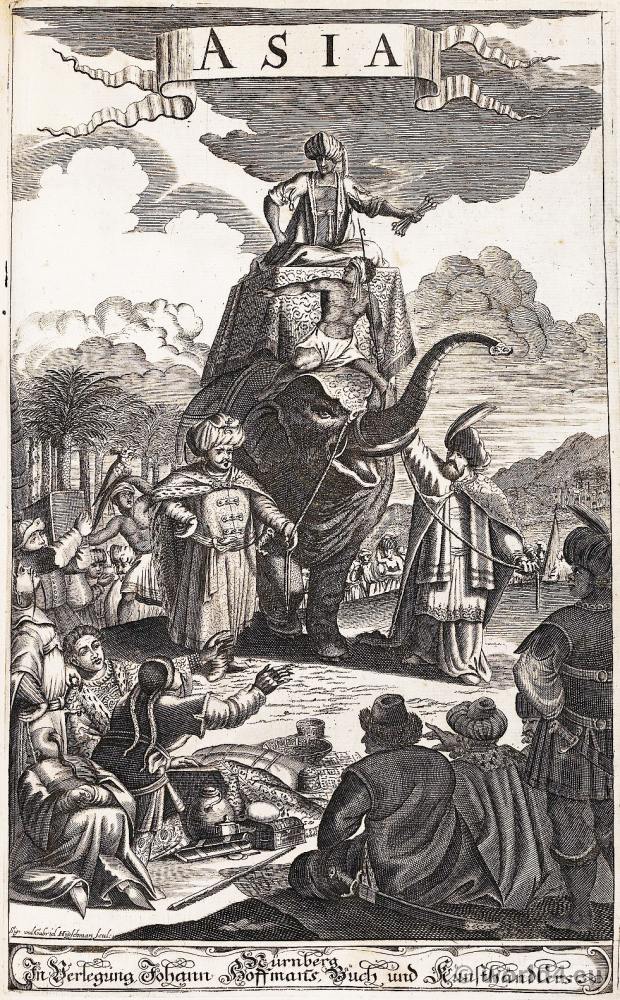

Frontispiz of the book: Asia, or: Detailed Description Of The Empire of the Great Mongols (Moghuls) and a great part of the Indies by Olfert Dapper in 1681.

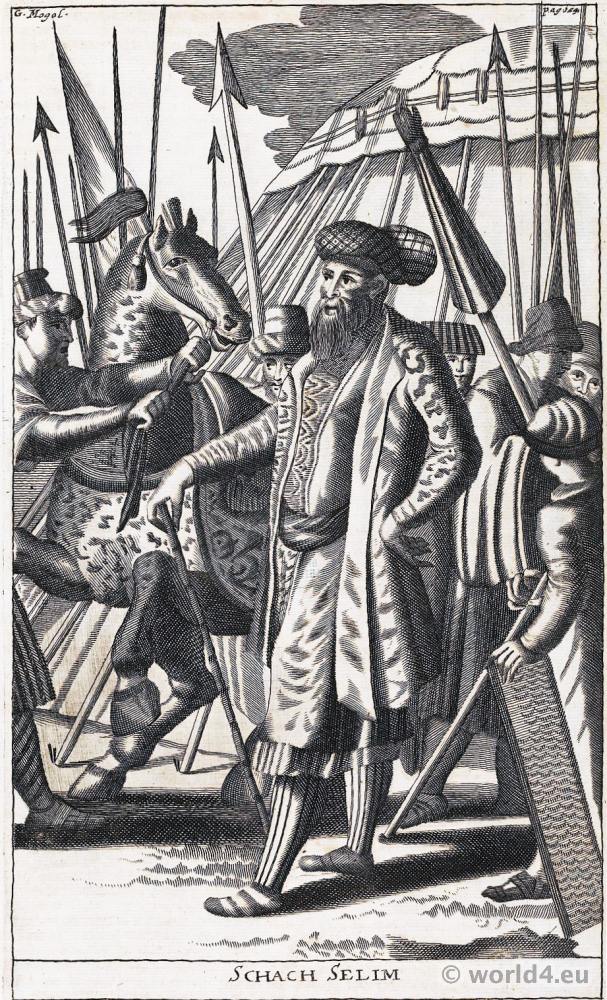

Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Mohammad Salim (1569 – 1627). Imperial name Jahangir.

Fifth Mughal Emperor Shah Shahabuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan (1592 – 1666). Builder of the Taj Mahal at Agra in memory of his third wife, Mumtaz Mahal.

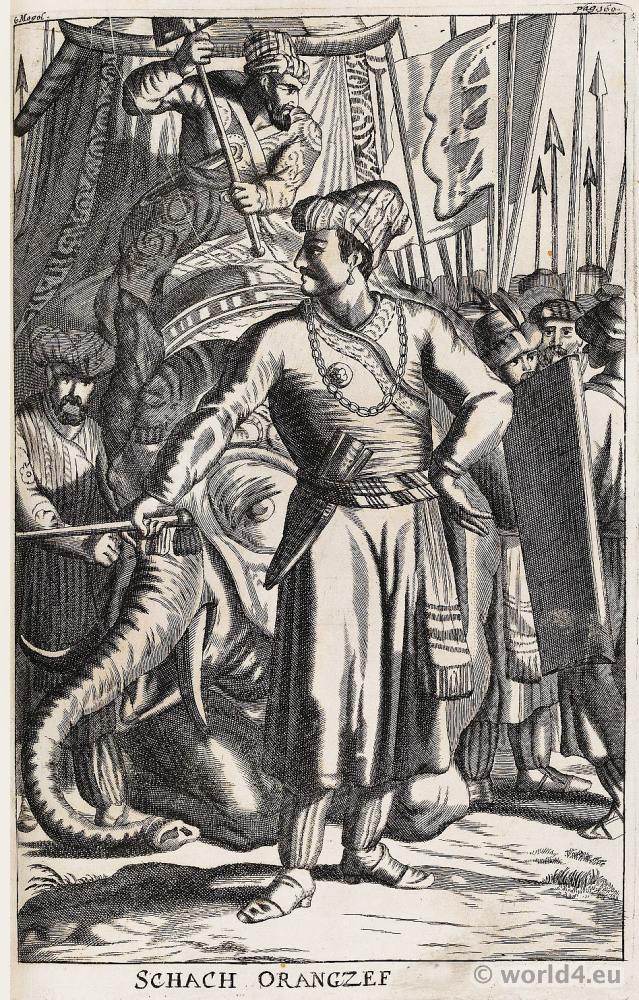

Sixth Mughal Emperor Shah Abul Muzaffar Muhi-ud-Din Mohammad Aurangzeb (1618 – 1707). Also known as Aurangzeb Alamgir and by his imperial title Alamgir.

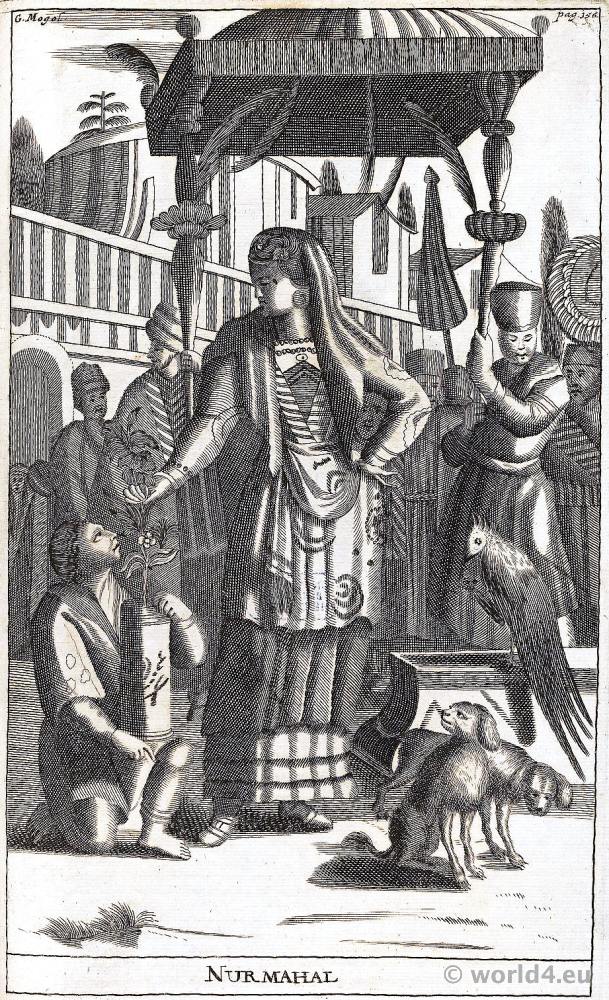

Mughal Empress Nur Jahan (1577 – 1645), called ‘Nur Mahal’ or ‘Light of the Palace’ Empress consort of Emperor Jahangir.

Humayun’s son Akbar, the most important Mughal ruler (reigned 1556-1605), who fortified the empire militarily, politically and economically, was a gifted statesman destined to wield the two racial elements into a cultural synthesis. He set out to remove all invidious distinctions between Muslims and non-Muslims. He meted out fair treatment to his Hindu subjects, appointed them to high posts and encouraged inter-racial marriages. He himself married two Rajput princesses. He pursued a policy of universal toleration by holding religious discourses. He was the first Mughal Emperor who did not sport a beard. All this gained him the love and reverence, the cooperation and goodwill of all his subjects and brought the Hindus and Muslims closer.

Not being fully satisfied with all these great social achievements, he tried to obliterate the communal differences in dress. His psychological insight told him that uniformity in appearance engendered a sense of belonging and a feeling of fraternity and harmony. As a step towards sartorial reform Akbar adopted a style of dress nearer to that of the Rajputs. The size of the turban was reduced and the kulah was detached from it. Earlier the Muslim jama had a frontal slit and was tied at the left side. Some women who had not fully overcome their initial shyness struck a compromise by wearing a ghagra instead of trousers beneath the skirt-slitted jama as they were apprehensive that the outlines of their limbs would show up through the frontal opening. Akbar ordered the jama to be made with round skirt without any slit and to be tied on the right side. Thus the new dress became a model of propriety and the fashion of the empire because the Emperor himself loved to wear his own innovated attire. In a reciprocal gesture some Rajputs also felt pride in imitating Iranian dresses. Each trying to become the other was an index of the flowering intimacy between the two communities.

Akbar also coined new and pleasing terms to be used in place of Persian names of various articles of dress: jama (coat) became sarab gati (that which covers the whole body); izar (trousers) was yar pairahan (companion of the coat); nim tanacha (jacket), tanzeb (adornment of the body); burqua (veil), chitragupita (face concealer); kulah (cap), sis shobha (adornment of the head); shal (shawl), parmnaram (that which is very soft); and paiafzar (shoes), charan dharan (that which covers the feet). Akbar also introduced the fashion of wearing the shawl doubled (doshalla).

After Akbar had ruled for four decades there was some change in the dress. The main elements of the costume were the coat, the turban and the trousers. Over a full sleeved undergarment was worn the half-sleeved long coat with three hanging V-shaped points in front and three at the back. The coat commonly known as jama was fitted tightly up to the waist and then like a skirt reached below the knees. At the chest it had two overlapping lapels. First the left lapel was taken beneath the right one and tied with its inner side by the help of ribbons already sewn in the garment. Then the right lapel was placed over the left and fastened by ribbons on the outer side of the left lapel. Numerous lapel flaps in a descending line were used on both sides of the chest. An Akbar type turban was worn. The waist was adorned by two bindings. A sash of gold brocade was displayed over a waistband of thin muslin. The motif on the hanging ends of the sash was geometrical, squares and triangles, and not floral. Trousers with puckers were visible below the lower edge of the jama.

Picture above: Farrukhsiyar and Babur, by Auguste Racinet. Upper left corner: A Mogul woman who has colored her upper body and face yellow with saffron dye. Center: The Mogul Emperor Farouksiar, who died in 1719, and the Emperor Houmaioun (upper right corner), who died in 1556.

Towards the end of sixteenth century, the jama was made of a diaphanous cloth, so transparent as to make visible the trousers beneath. It was a garment for summer wear. Most Rajasthani men, both from upper and middle classes, wore almost the same style of dress as was prevalent in Mughal courts. The costume had three varieties of jama. The most common was the one reaching below the knee. The other had pointed ends, four around 1560 and six around 1580. Sometimes these points became very sharp and elongated, reaching almost to the ankles. There was a third type long enough to cover almost the whole of the trousers but it was not as popular as the first two. Sometimes the jama had full sleeves.

Most women in northern India, however, were hesitant to copy an exotic dress and continued to prefer the halfsleeved bodice (choli), the ankle-length skirt (ghagra) and the head-scarf (orhni). The upper garment was fully embroidered at the neck and sleeves and the tasselled ends of the transparent orhni were decorated with pompoms. Pompom, an ornamental ball of wool or silk, was very much in fashion. They were found on the strings that tied armlets and bracelets, on shoes at the end of dangling tassels, and on the hair. But wives of noblemen and officials and high ranking ladies, bewitched with the magnetic influence and beauty of the Mughal style, adopted the Mughal jama with flowing skirt, the tight trousers and the orhni. The ends of a decorated sash worn underneath the jama are visible.

The Fascination of the Mughal Empire.

The name “Mogul” as a designation for the rulers of northern India was probably formed in the 16th century by the Portuguese (Portuguese Grão Mogor or Grão Mogol “Grand Mogul”), who established a Jesuit mission at the court of Akbar as early as 1580, and later adopted by other European travellers to India. It is derived from the Persian مغول mughul and means “Mongolian”. Originally, “Mog(h)ulistan” denoted the Central Asian Chagatai Khanate. The latter was the home of Timur Lang, founder of the Timurid dynasty and direct ancestor of the first Mughal ruler Babur.

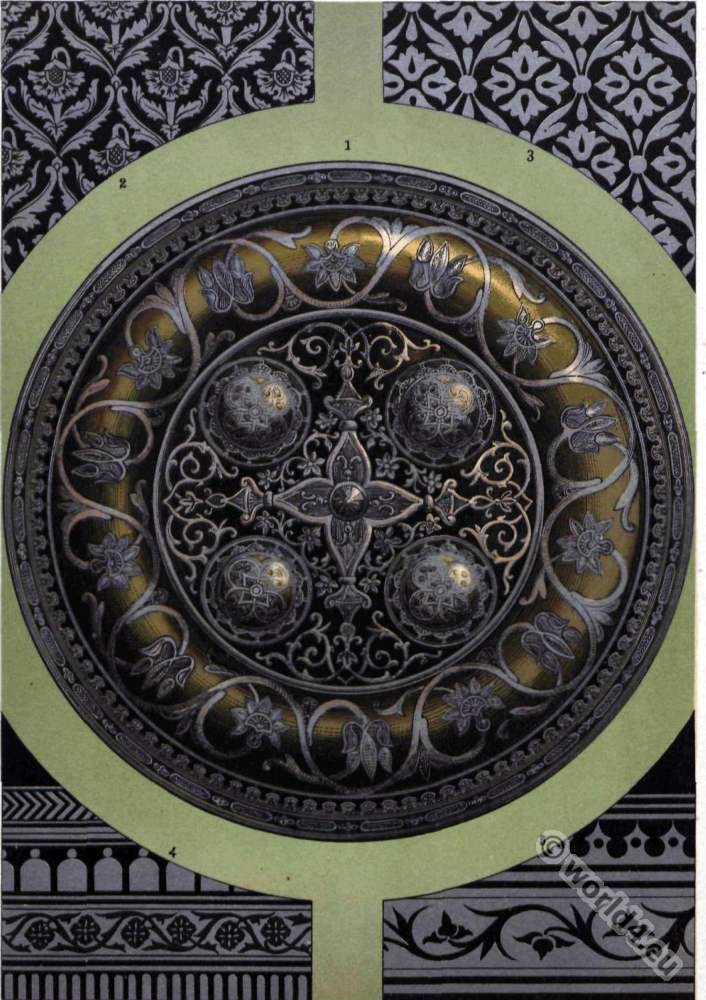

Indian art. 1. Shield. 2,3,4, and 5. details of decoration in jugs, dishes and basins.

Indian art. 1. Detail of an ewer belonging to the Baroness de Rothschild. 2. Ditto another belonging to M. Leonico Mahou.

Mughal Empire. Indian Helmet, shield and swords. Battle axe and Martel with Sheath.

Ornamented Weapons from East India. J.B. Waring’s “MASTERPIECES OF INDUSTRIAL ART & SCULPTURE” published by Day & Son in London in 1863. Dedicated to her Majesty, the Queen.

Above picture from: Ceremonies and Religious Customs of the Various Nations 1723. Engraver Bernard Picart. Publisher: Jean Frederic Bernard.

Although the name correctly refers to the Mongolian descent of the Indian dynasty, it does not take into account the more precise relationship to the Mongolian empire. This is expressed in the Persian proper noun گوركانى gūrkānī of the Mughals, which is derived from the Mongolian cüraegian “son-in-law” – an allusion to Timur’s marriage into the family of Genghis Khan. Accordingly, the Persian name for the Mughal dynasty is گورکانیان Gūrkānīyān. In Urdu, however, the Mughal Emperor is called مغل باد شاہ Mughal Bādšāh.

Above picture: Mughal emperor leading a Military Shipping. Babur setting out with his army.

Costume de Guerre du XVIe siècle. Empereur Mogol conduisant une Expédition Militaire.Ces fragments sont tirés d’une peinture représentant Djahir-el-din Mohammed, surnommé Bâber (le Tigre), roi et empereur des Indes, partant à la tête de son armée pour envahir la province de Mazindera, en Perse. X Auguste Racinet

These fragments are from a painting of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muḥammad (1483–1530), nicknamed Babur (Persian babr, meaning Tiger) reign 1526–1530, eldest son of Umar Sheikh Mirza. The King and Emperor of India, leaving at the head of his army to invade the province of Mazindera, Persia. He was the Indian emperor and founder of the Mughal dynasty of India, a descendant of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan and also of Timur (Tamerlane).

He was a military adventurer and soldier of distinction and a poet and diarist of genius, as well as a statesman. Babur is rightly considered the founder of the Indian Mughal Empire, even though the work of consolidating the empire was performed by his grandson Akbar.

Babur, moreover, provided the glamour of magnetic leadership that inspired the next two generations. Babur was a military adventurer of genius, an empire builder of good fortune, and an engaging personality. He was also a Turkey poet of considerable gifts that would have won him distinction apart from his political career.

He was a lover of nature who constructed gardens wherever he went and complemented beautiful spots by holding convivial parties. Finally, his prose memoirs, the Babur-nameh, have become a world classic of autobiography. They were translated from Turki into Persian in Akbar’s reign (1589) and were translated into English in two volumes in 1921-22 with the title Memoirs of Babur.

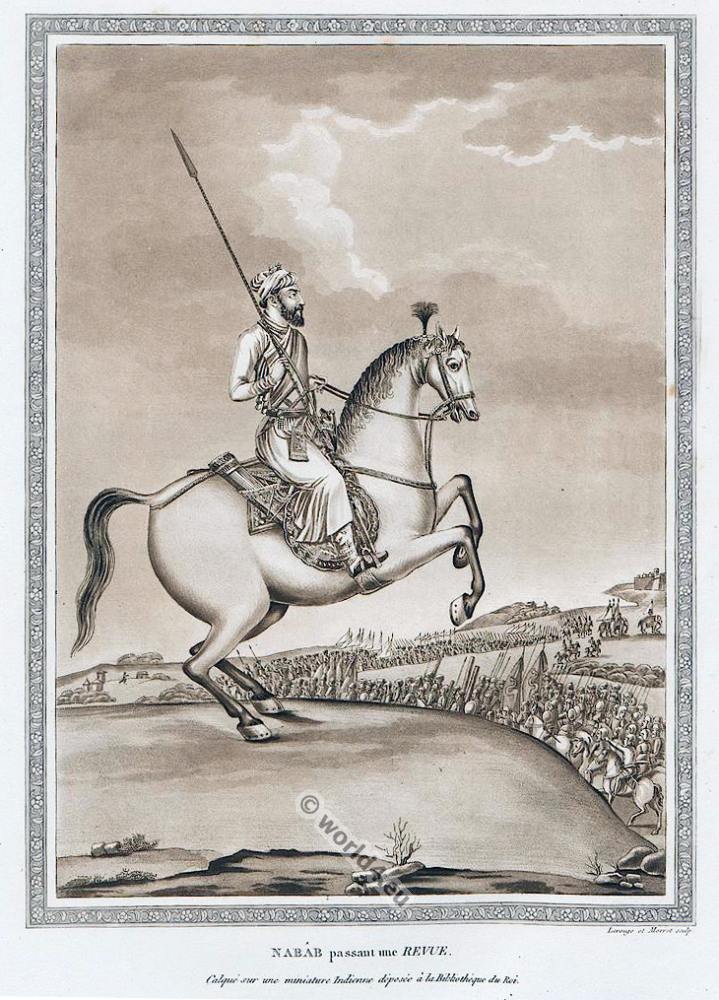

The Mogul is represented with all the attributes of the ruler, especially the parasol, carried over him. He is wearing a silk jacket, short sleeved, and a round shaped skirt, with ornamental design and large metal button-plate on his chest.

The jacked is padded to protect against the arrows and his knees are also protected by metal plates. In his right hand, he is holding one of the offensive weapons of the time, a spear, with ends being finished with decorated metal, on the left side he wears a saber and on his belt, a quiver with feather arrows is attached.

The soldier behind him carries a hammer like weapon, which could also be a heavy wood club, he is holding it with both his hands, indicating the heaviness of the weapon. The mogul’s horse is entirely protected with armor of overlapped blades.

An interesting feature is that he does not were the rider’s boots but his personal slippers. Another interesting feature of this painting is the lack of elephants in his army. Before the ruler, we see a number of infantrymen who proceed him and by shouting create a necessary room for him to pass.”

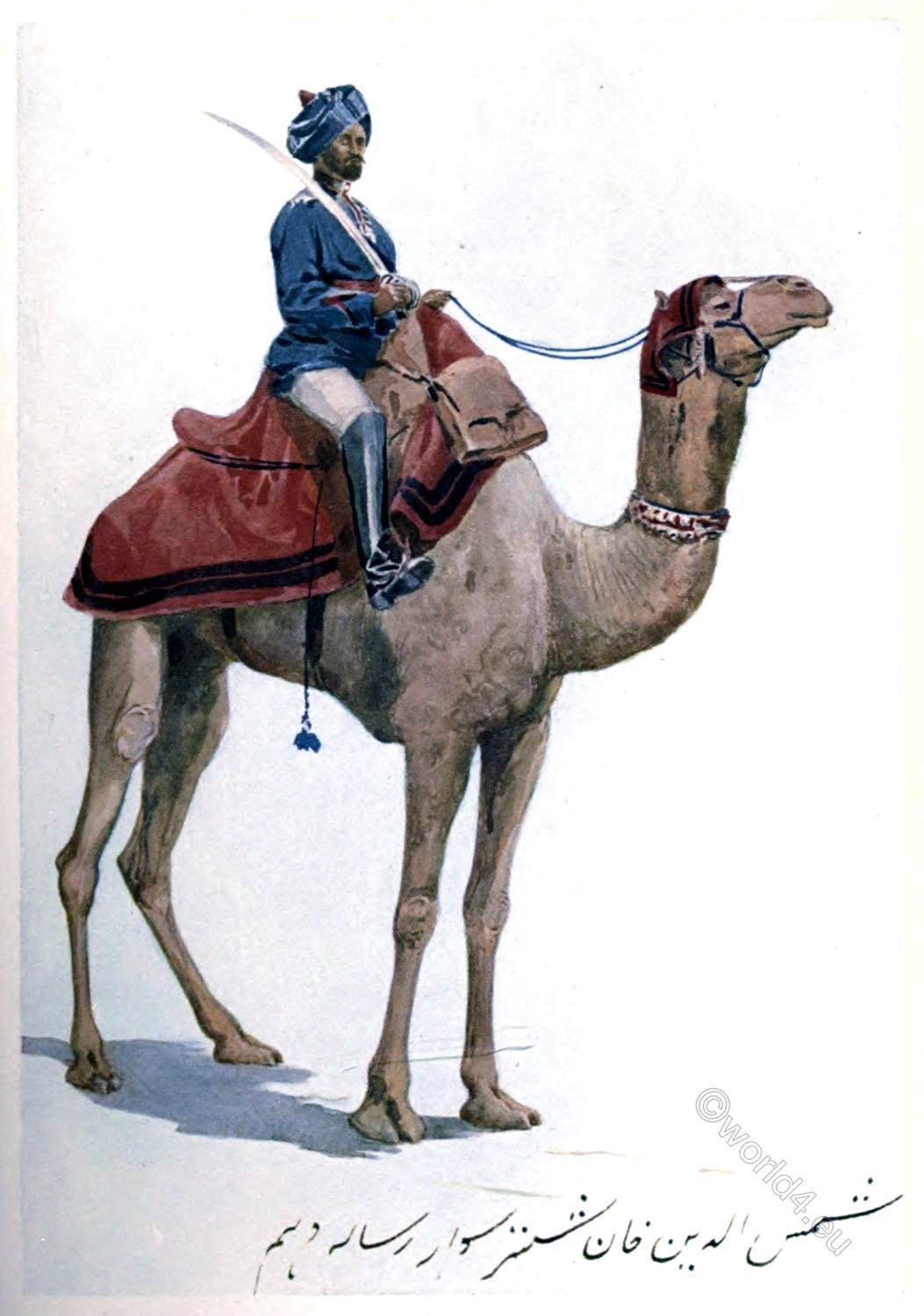

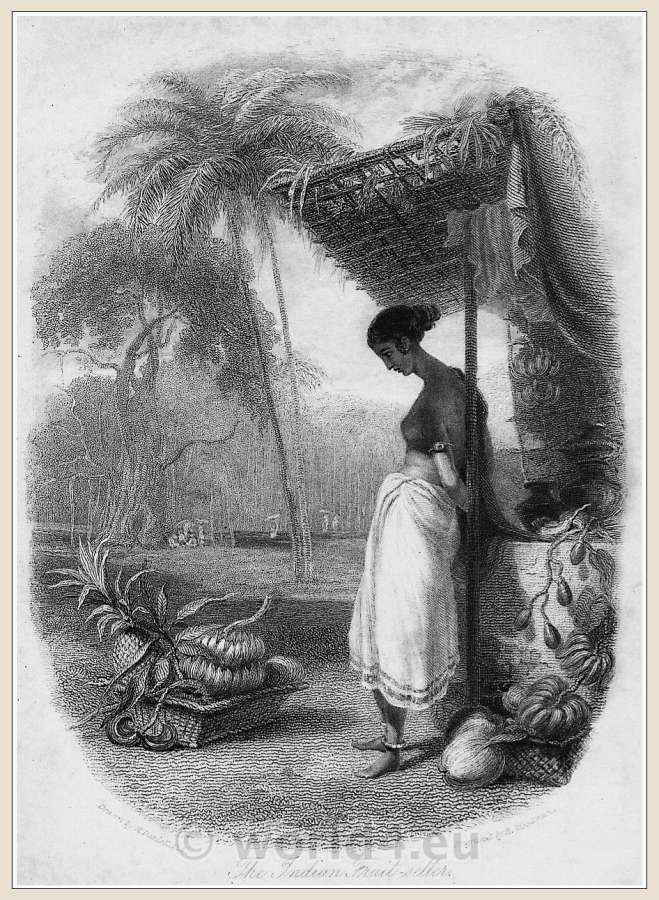

Above: India in words and pictures: a description of the Indian Empire by Emil Schlagintweit, 1881.

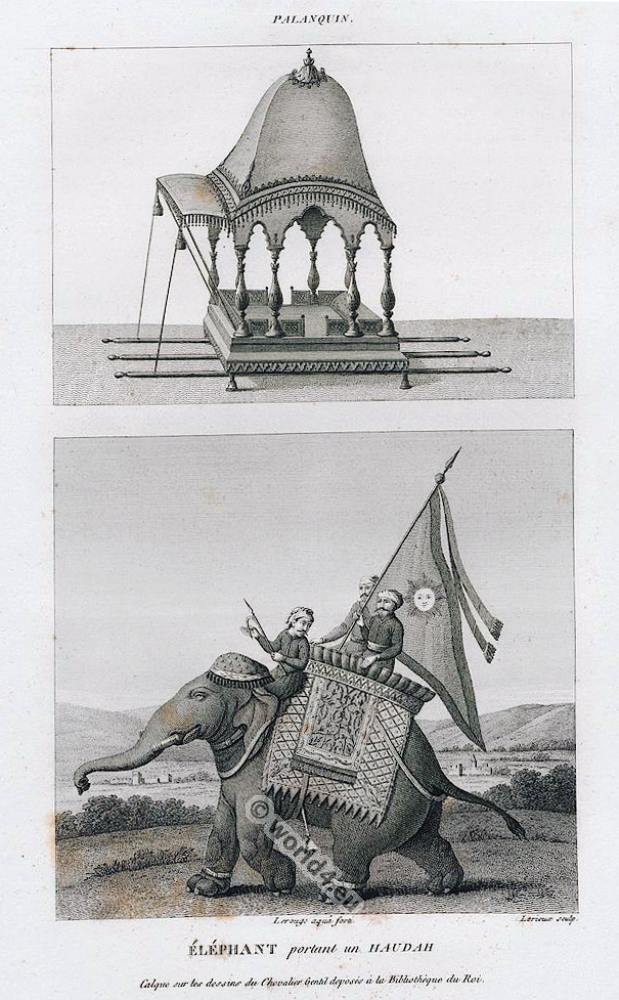

Above pictures from the book: Asia, or: Detailed Description Of The Empire of the Great Mongols (Moghuls) and a great part of the Indies, by Olfert Dapper in 1681.

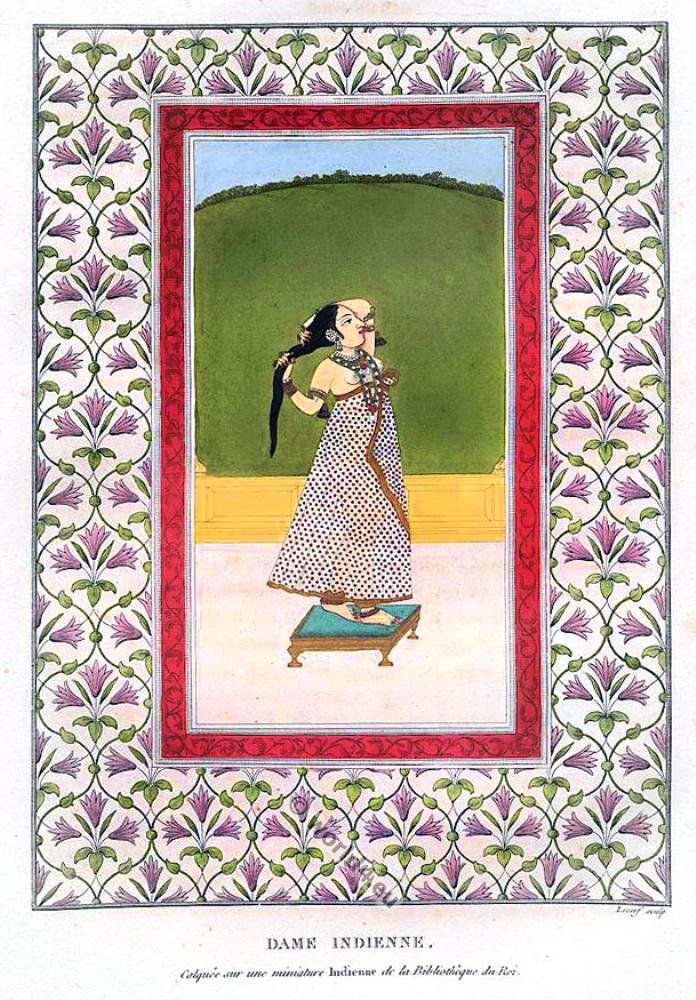

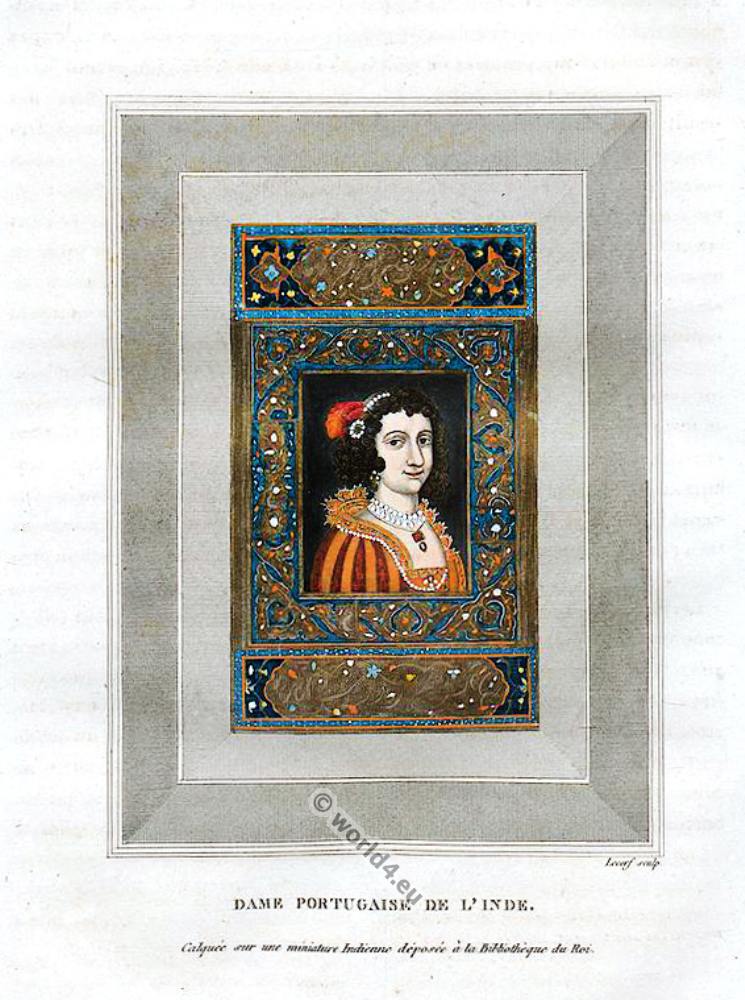

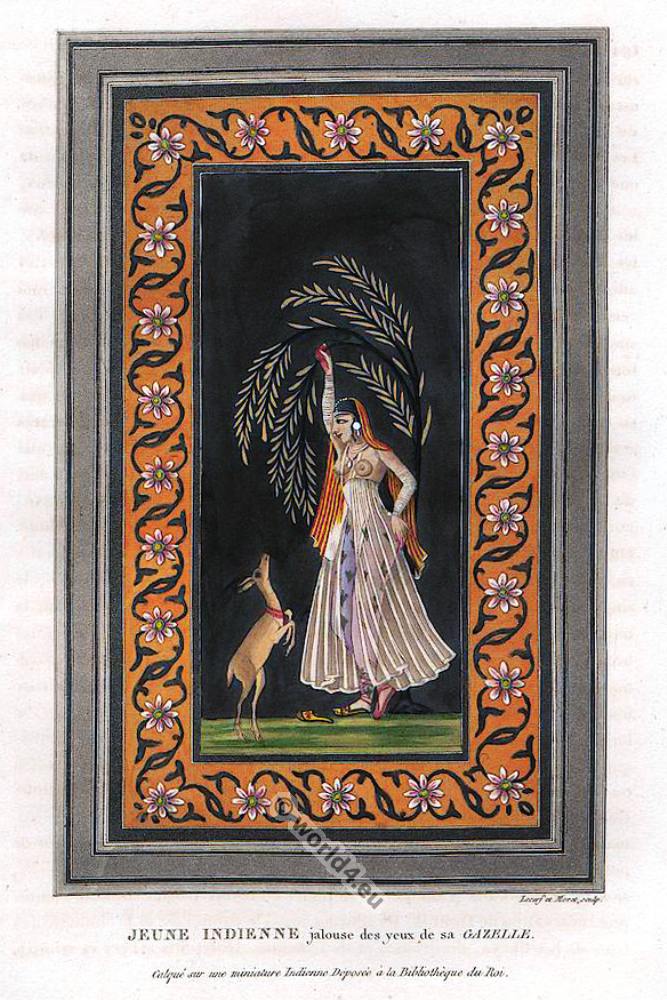

Mughal miniature paintings.

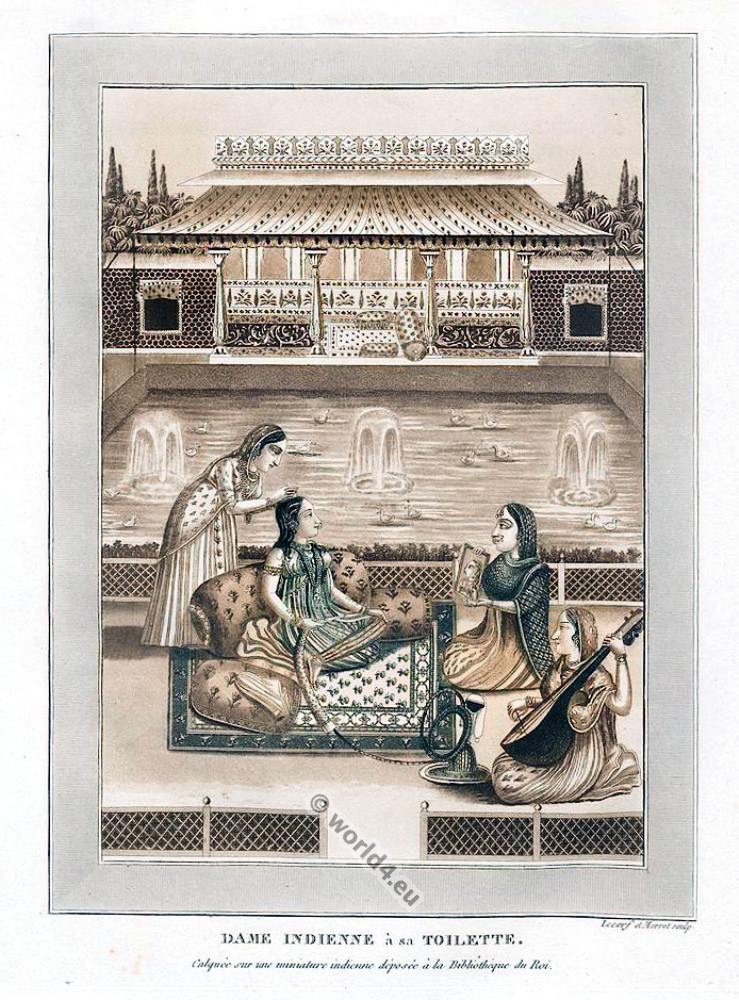

Above pictures from the book: Monuments anciens et modernes de l’Hindoustan, decrits sous le double rapport archaeologique et pittoresque, et precedes d’une notice geographique, d’une notice historique, et d’un discours sur la religion, la legislation et les moeurs des hindous. Louis Mathieu Langlès. Paris: P. Didot, 1821.

Literature:

- Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire. Published to accompany a major British Library exhibition, Mughal India showcases the British Library’s extensive collection of illustrated manuscripts and paintings commissioned by Mughal emperors and other officials.

- Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India

- Indian Textiles (Revised and Expanded Edition)

- Handmade in India: A Geographic Encyclopedia of India Handicrafts

- Nomadic Embroideries: India’s Tribal Textile Art

- Ralli Quilts: Traditional Textiles from Pakistan and India (Schiffer Book for Designers and Collectors)

- V&A Pattern: Indian Florals: (Hardcover with CD)

- Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West

- Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500 to 1800

- Les civilisations de l’Inde by Gustave Le Bon. Paris: Firmin-Didot et cie, 1887.