NAPLES

FROM THE CASTLE OF ST. ELMO.

PLATE XL.

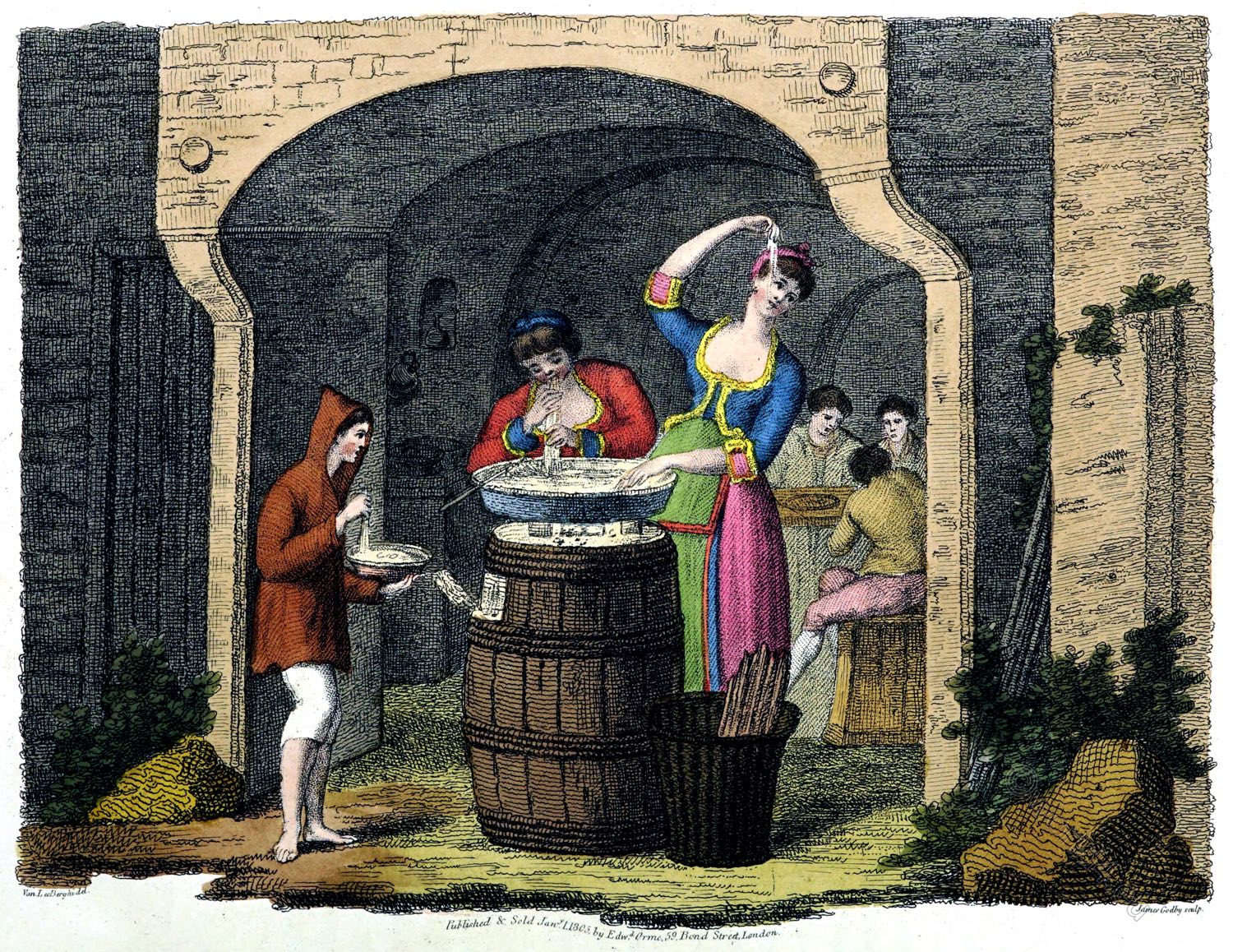

Great part of the road from Rome to Naples passes over the ancient Appian way; the distance is about one hundred and fifty miles, sufficient, we may imagine, to prepare the mind of the traveller for some alteration of character in the inhabitants, as well as scenery: but it will be scarcely possible for him to conceive the total contrast between those two cities. He will have left the abode of dullness and monastic monotony, of which the deserted regions are every where too large for their secluded inhabitants; and he will arrive at the capital of gaiety, bustle, and confusion, where an exuberant population seems poured out upon the public quays, and where parading the streets seems to be the principal occupation of every individual.

At Rome he will have observed the beautiful remains of ancient taste presenting their fine forms in every quarter he visited, but perhaps eclipsed by buildings exhibiting the triumph of modern architecture, and the display of ecclesiastic wealth.

At Naples, the total absence of both these features cannot fail to be remarked, since there, no remains of ancient beauty or magnificence exist; while the modern edifices derive their importance entirely from their magnitude or internal decoration. The former is old, and in the last period of decline, with the mal aria, not however unknown to Horace, advancing its fatal prevalence; but the latter is at present more opulent, more populous, and in every respect more flourishing, than she has ever been during the most brilliant periods of her history.

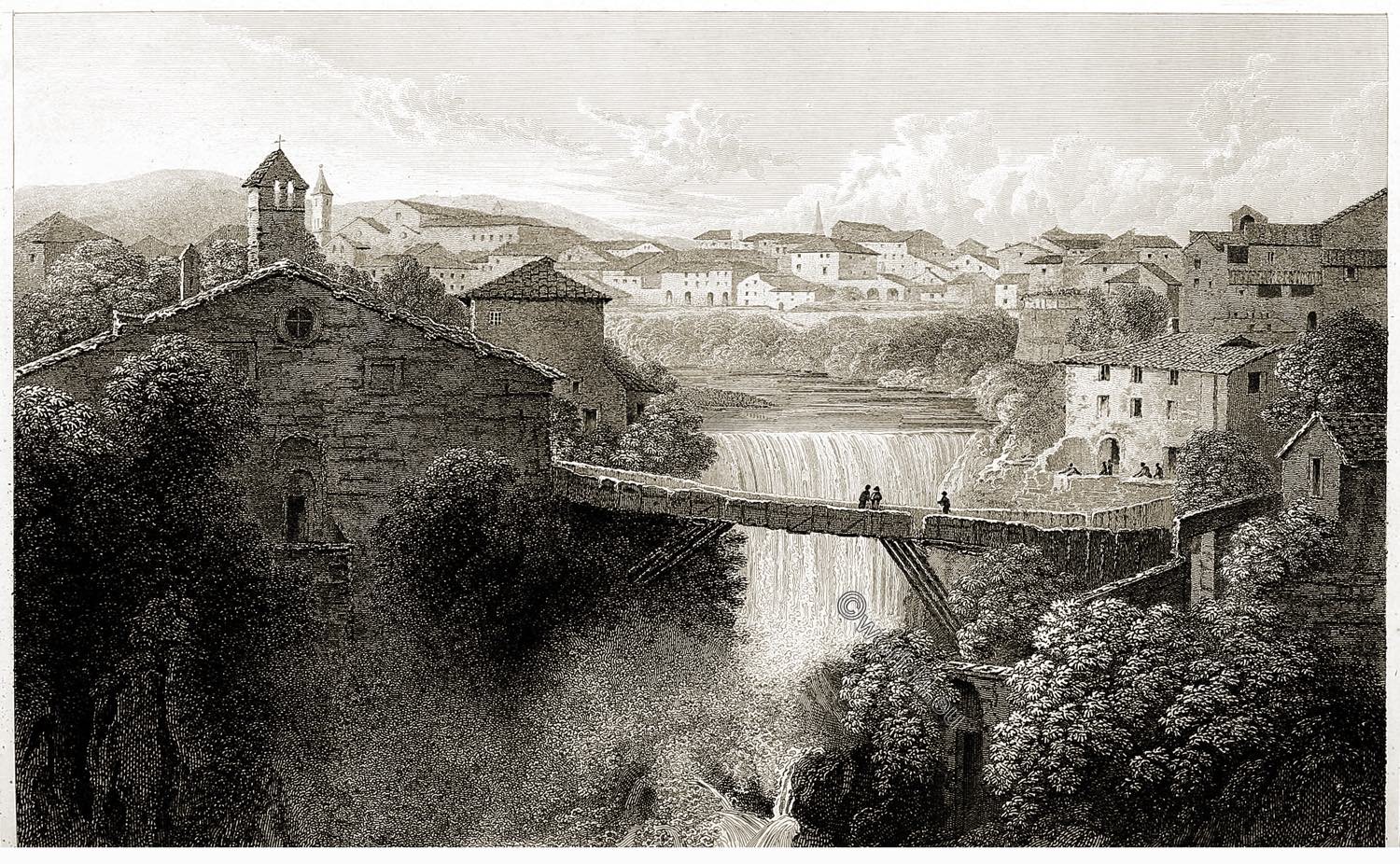

But Eustace has well observed that few cities stand in less need of architectural decoration or internal attractions, so beautiful its neighborhood, so delicious its climate:— before it spreads the sea, with its bays, promontories, and islands; behind it rises mountains and rocks, in every fantastic variety of form, always clothed with verdure.

On each side swell hills and hillocks, covered with groves, and gardens, and orchards, blooming with fruits and flowers. Every morning, gales springing from the sea, bring vigor and coolness, tempering the heats of summer with their freshness; every evening, breezes blow from the hills, sweeping the perfume of the country before them, and filling the nightly atmosphere with fragrance.

The city, in size and number of inhabitants, ranks, at present, as third in Europe; and, from her situation and superb show, may be considered the Queen of the Mediterranean: the feminine appellation she is justly entitled to, since at no period does she appear to have taken the slightest part in her own defense, but ever to have fallen to those who successfully entered the lists for her possession.

Naples was anciently distinguished into two separate portions, bearing the names of Palaepolis and Neapolis; the former indicating the more ancient city ruined by the Cumans, and the latter pointing out the portion afterwards rebuilt by that people, in conformity with the dictates of an oracle, which declared it to be the only means of putting an end to the ravages of a pestilence then infecting their city.

The whole was surrounded with walls, strong enough to afford the appearance of resistance to the meditated attacks of Hannibal, and sufficient to deter that leader from attempting its siege. Smarting under the effects of their want of success in the Samnite war, a voluntary loan, or rather forced gift, had been extorted from their pusillanimity by their Roman masters, as an earnest of their faith in the later contest.

From this period, to the expedition under Belisarius, Naples enjoyed a comparative state of tranquillity; and its neighborhood was principally distinguished as the retreat of the opulent Romans: but that general having taken, delivered it over to the pillage of his soldiery; though, as his office was to restore the tottering empire, he set up its sacked abodes; and the historians of the time declare him accordingly to have raised it from ruin.

Pope Innocent IV. here died, in the middle of the thirteenth century, having made it his residence, and strengthened its defences.

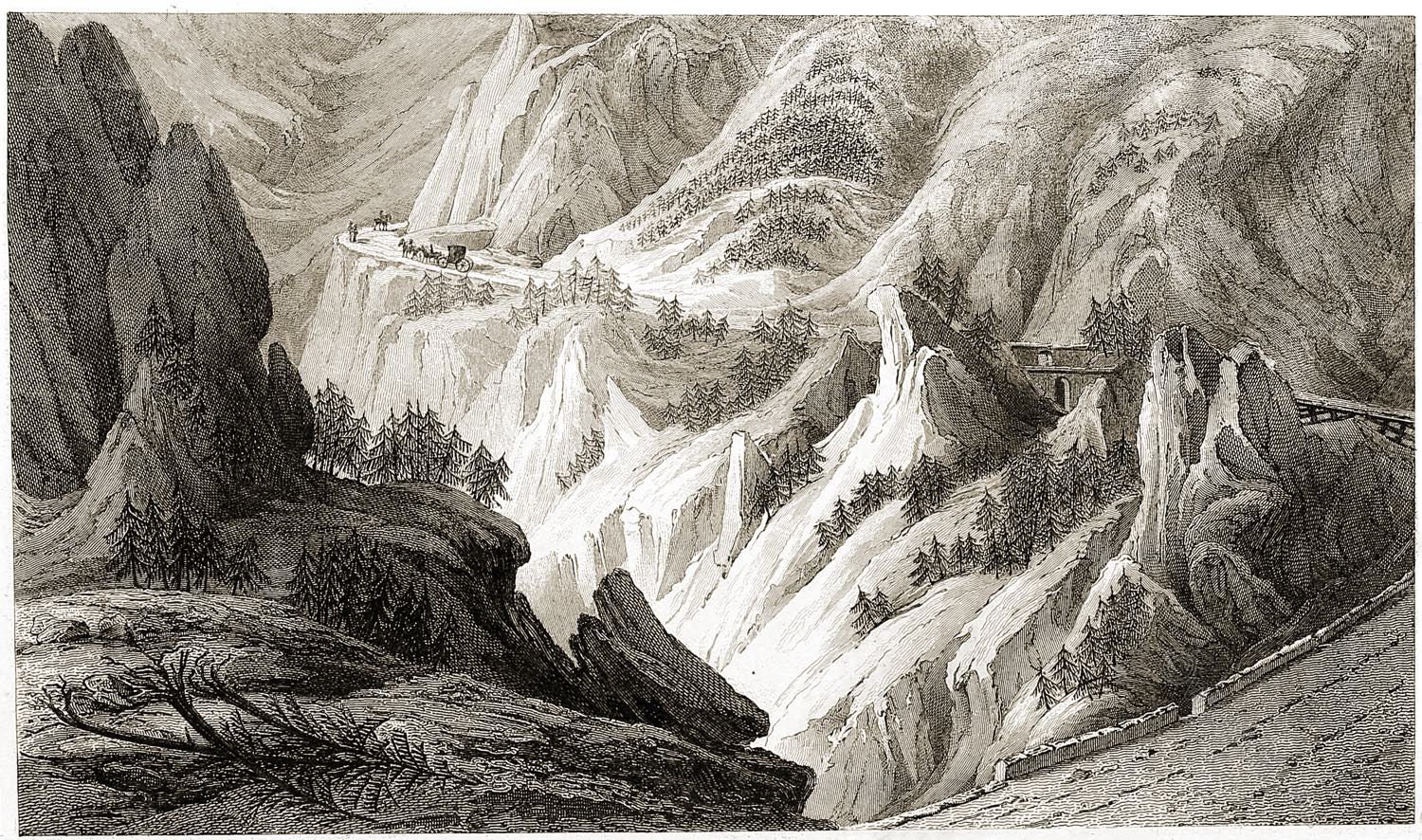

Charles of Anjou soon after added the Castel Nuovo, and his son raised the Castle St. Elmo, better calculated to keep in order a lazy population of 400,000 souls, than for defense against an extraneous enemy; although, as from its central and lofty situation, it completely commands the whole city of Naples, it has been at all periods considered of essential importance to its security.

The strength of this castle was, however, first made really efficient under Charles V. by means of ditches and other works cut out of the solid rock, while more modern science has improved the whole into a regular and important fortification.

Besides the Castle of St. Elmo, this hill was occupied by a convent of Carthusians, dedicated to St. Martin, and placed under the castle in a most agreeable and commanding situation; advantages which had originally occasioned the selection of its site for the erection of a royal palace, relinquished in the fourteenth century by Robert of Anjou, at the instance of his son Charles, to the religious order which afterwards enjoyed its possession.

This prince never reigned; but the monastery he began to erect, and the revenues with which he endowed the establishment, were perfected and augmented by his daughter, to whom, at his death, he left, with the kingdom, the charge of completing the undertaking.

The church is more modern, and adorned with pavements of marble, as well as a cupola of gilding and painting, besides some pieces by Spagnoletti, amongst which are the twelve apostles.— Giordano, Guido, and other masters, have likewise had a share in this part of its decoration.

The view from the terrace and gardens of the monastery, over the most delightfully placed city in Italy, is striking, but perhaps too extensive; Vesuvius, in the midst, conceals the plain of Nola, beyond which the mountains, rising from the cape of Sorento, bound the scene; and through the midst the bay sweeps its blue waves, bringing their perennial tribute of never- failing breezes to the most delicious climate of Europe.

From this spot the forked top of Vesuvius is perhaps more intelligible than upon a nearer inspection.

The more recent cone, whence the later eruptions have been ejected, appears to the right, clearly distinguishable from the remains of the original crater on the left, from the bosom of which the former appears to arise: the space between them is a valley, bending to the form of the mountain, and which was once remarkable for its vegetation, whence it was called Atrio di Cavalli; a name it has not lost, although the ravages of the volcano have reduced it to a scene of desolation, exhibiting nothing but the scoriae of repeated eruptions— perhaps the symbol of the fate awaiting the city below; since the volcano has certainly gone on progressively increasing in bulk from the period of its first phenomena, or rather from a period beyond the records of man.

Whether the stupendous form of Etna has existed from all ages, may afford matter for philosophic speculation.

Vesuvius is certainly in its infancy: its progress towards maturity may involve consequences which, if not alarming to those in its immediate vicinity, may at least serve to content the inhabitants of climes, which, although less genial, are at the same time free from apprehension of the calamities attending these tremendous workings of nature.

Source: Italian scenery from drawings made in 1817 by Elizabeth Frances Batty. London: Published by Rodwell & Martin, 1820.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.