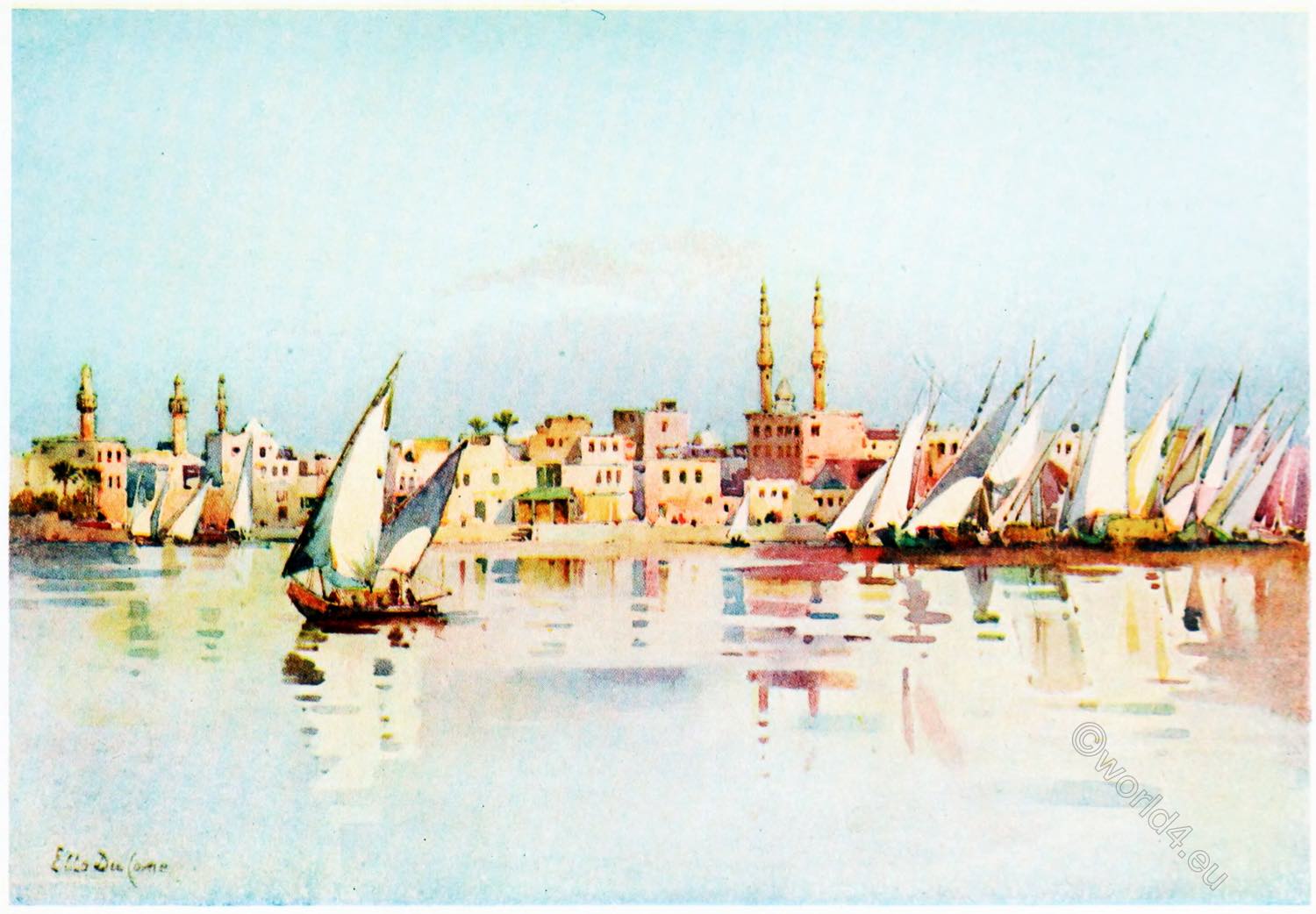

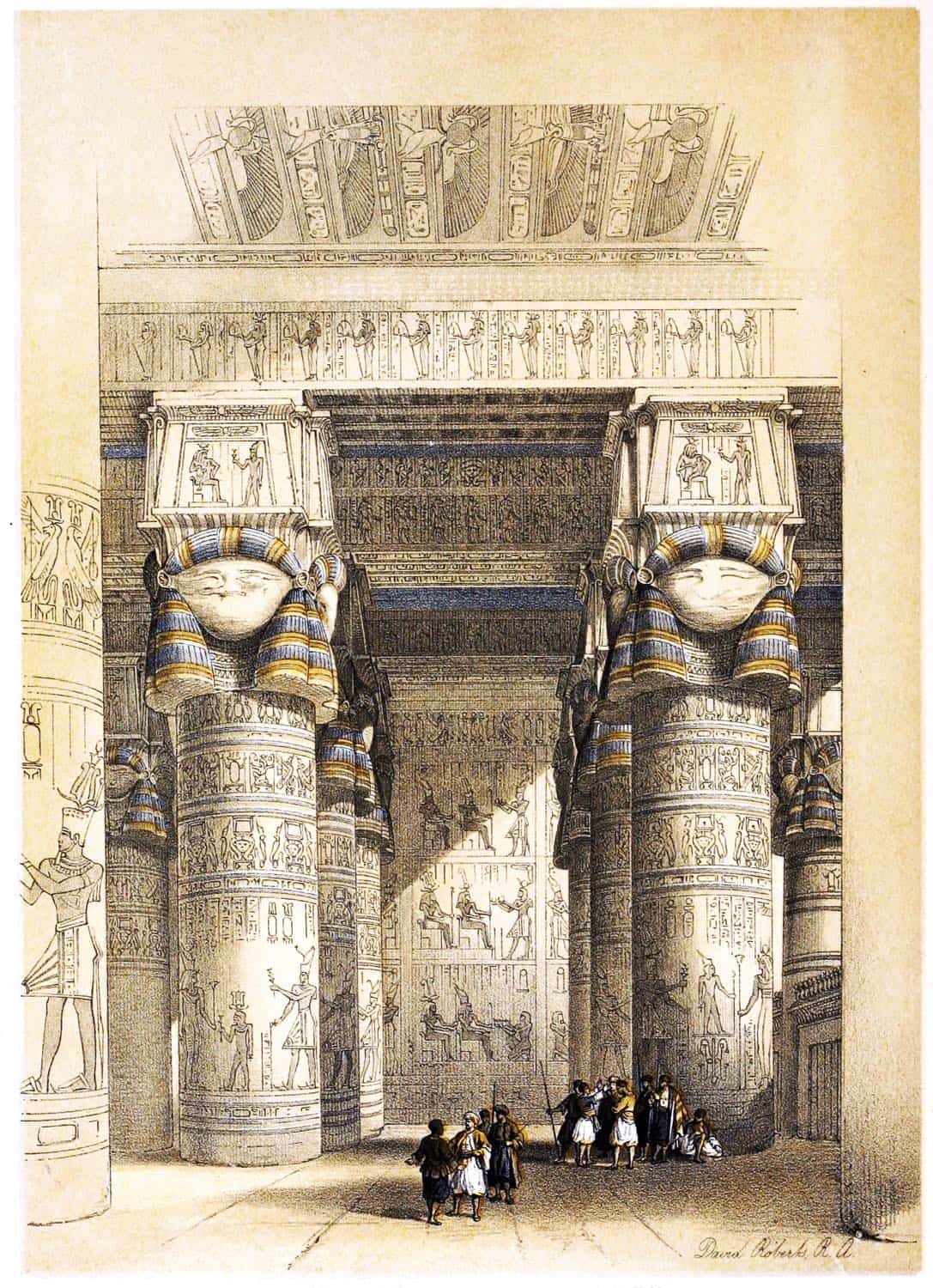

THE APPROACH TO PHILAE.

THIS is one of the few views which a photograph can render without, perhaps, greatly detracting from its artistic fame. Everybody has sketched it— many clever artists have painted it — Murray has engraved it for his “Guide,” and now, in these later days, the Sun himself condescends to pigmify it, and pop it bodily into the box which your artist provided. And it is a view which can bear all this treatment—this freedom of travelers—this robbery—above all, this unflattering mechanical picture-making, without loss of beauty or interest.

We recollect to have exhausted, in a previous article, our philosophy of the combination of causes which give to the Island of Philae its just fame for impressive loveliness: several of those features may be gathered from a study of this picture.

Observe, especially, the peculiarly bold and quaint formation of the granite rock, and the singularly harmonious effect of the old Egyptian architecture, rising, like a vision of a giant fairy-land, from the midst of these weird stones and waters;—for one becomes accustomed to look upon the old river itself—from its physical peculiarities, and its ruins, and its crocodiles—as being, at any rate, largely implicated in all these mysteries and wonders.

How well do I recollect that it was a moment of happy excitement when our party, after being hauled up the cataract, reached the point from which my view is taken. In all sincerity, we were deeply impressed by the combined beauty and interest ol the scene. It has been well, but too often, said that the priests of old Egypt judiciously chose this spot as the seat of their most sacred and mysterious rites.

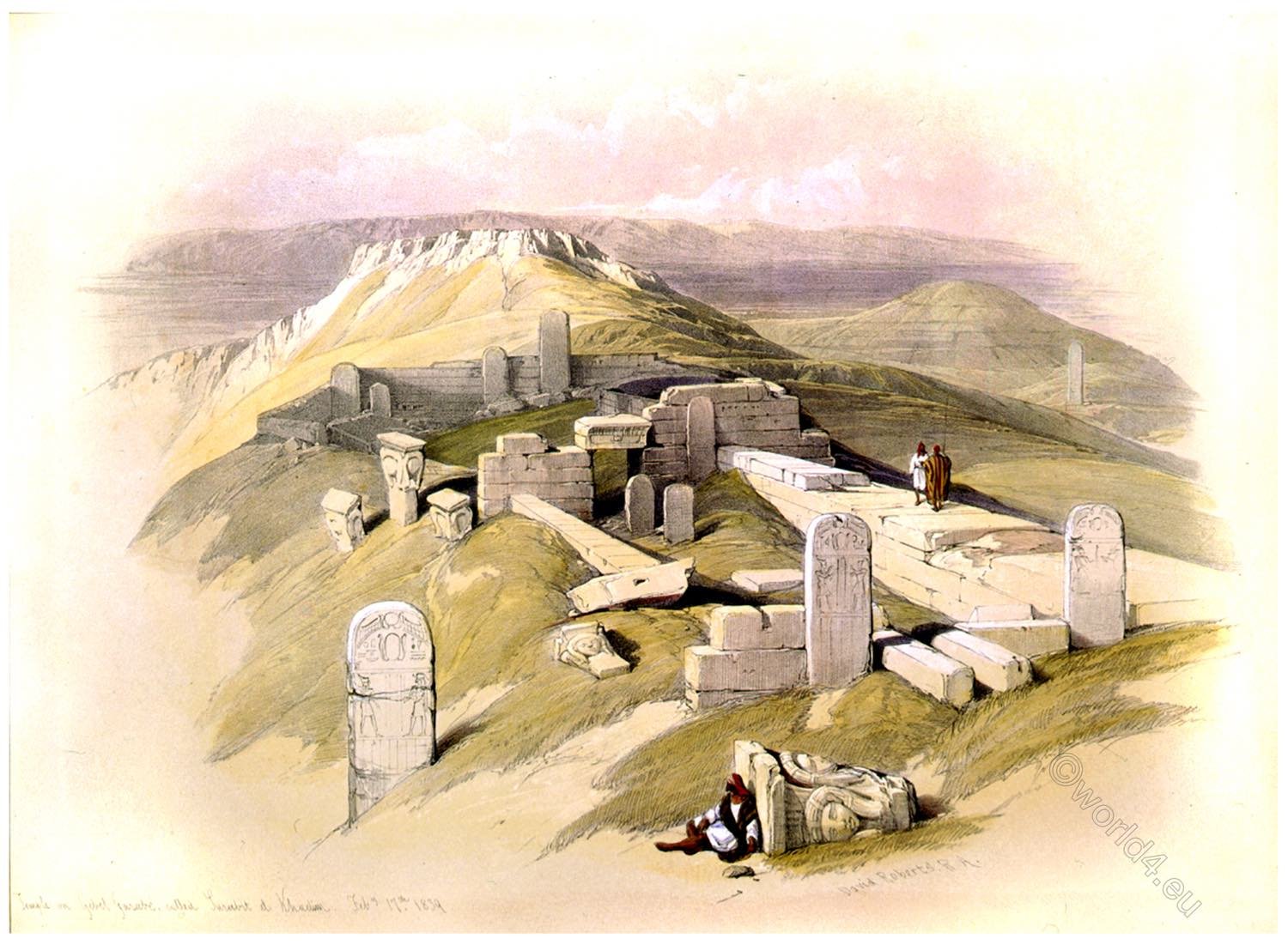

It was well feigned to be the burial-place of Osiris; and the oath, “By him who sleeps in Philae,” was an oath of solemn sounding, and poetic significance. I think I recollect, too, that the place was ingeniously rendered yet more sacred by the necessary resurrection of this deity. His consort, Isis, was also appropriately worshipped here; and, not less consistently followed, in due time, to complete the honor and sanctity of the spot, the birth of their son, the god Horus.

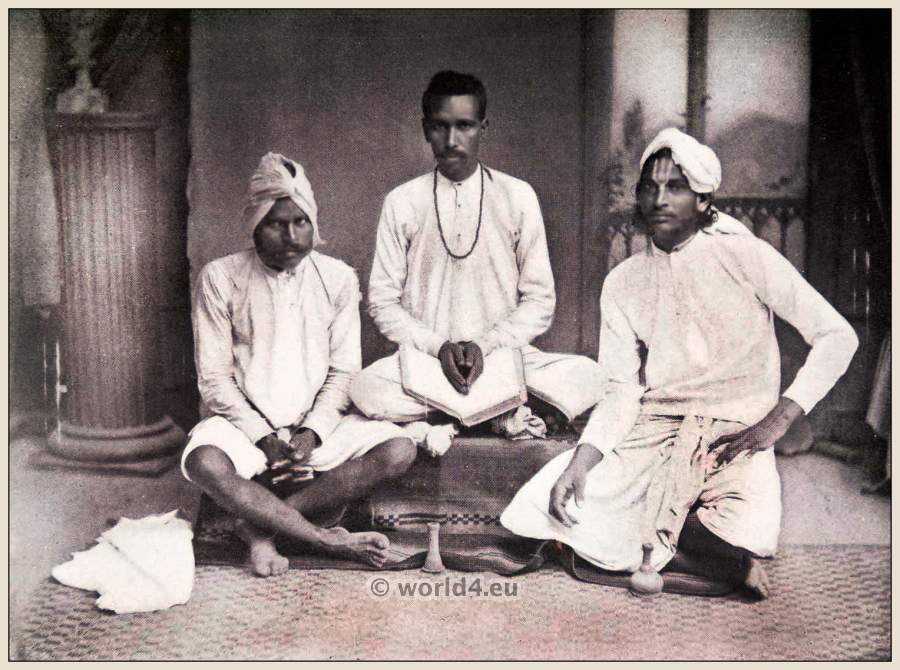

The ridge of granite rocks commencing here, then forming the first cataract, and losing itself six miles below, at Aswan, constitutes the boundary between Egypt and Nubia. Above this spot, the strip of cultivable land on each bank of the river is very small—perhaps not averaging more than a quarter of a mile in width. The inhabitants have been celebrated by many travelers for their beauty of figure and feature, and for the rich bronze color of their skins.

The item of feature I should be strongly inclined to dispute with any traveller not better qualified, by his opportunities, of forming a judgment than I myself have enjoyed. The women, for the most part, are severely hideous; the only interesting feature that I remarked in them is that they wear their black hair—stiff and shiny with a life-long accumulation of castor-oil—in innumerable little black twists, precisely as we see the hair-dress of women represented in the sculptures of three thousand years ago— a most striking illustration of the perpetuity of a singular national custom.

Some travelers—amongst them Dr. Brutsch— discern also a strong resemblance in the physiognomy of these natives, to that of the ordinary type of feature represented in Egyptian sculpture.

Source: Egypt and Palestine by Francis Frith, 1858. Publisher: London, James S. Virtue, City Road and Ivy Lane. New York: 26, John Street.

Continuing