Fashion in the time of William I. The Conquerer & Matilda of Flanders.

England. Reign of William I. 1066-1087.

Nobility-Men

All trace of Scandinavian elements in Art and Costume had disappeared from the Norman race in France by the eleventh century, but they still retained the fierce and turbulent nature, and ardour for war, characteristic of their race. Their costume was like that in use in all other countries in Western Europe, and much influenced by the fashions of Byzantium.

Many interesting details of this period can be gleaned from the Bayeux Tapestry. Copies are to be found in many museums;*) For the most part the costumes depicted are military in character, and the English are represented wearing Norman military accoutrements; but this is an ingenuous mistake on the part of the queen and her ladies, who were not present on the battlefield, but assumed that the English must have been dressed in the same manner as their own countrymen. Some civilians are included, but only two women.

*) The Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, is one.

William I. (born at Falaise, 1027) was exceedingly tall, with a finely proportioned figure. His face was handsome, he had an aquiline nose, quick grey eyes, high forehead, and dark moderately short hair, but his countenance was stern and commanding. When he chose, he could assume a very winning smile, so that few could resist him, but when angry no one dare approach him. By nature he is said to have been cruel, but most of his actions prove him a just judge, a man of great discernment, and even sympathetic.

The death of the handsome Earl Waltheof in 1076 has been laid at William’s door, but the treachery of Waltheof’s wife, Judith, and the greed of his enemies are much more to blame.

See also:

- The armorial bearings of the Monarchs of The Royal House of Normandy.

- Fashion in the time of William II. 1087-1100. England Anglo-Norman.

In middle age William became bald, and in later life very corpulent. As he rode round the burning city of Mantes, which he had taken, his horse reared and threw him against the pommel of his saddle, inflicting internal injuries. He was removed to Rouen, where he expired on the ides (9th) of September, 1087, and was interred in the Abbey of S. Stephen, Caen.

The physicians and others who were present at the death of the Conqueror lost their wits. Alarmed by their anticipation of troubles in the near future, the wealthiest of them mounted their horses and departed in haste to secure their own property. But the inferior attendants, observing that their masters had disappeared, laid hands on the arms, the plate, the robes, the linen, and all the royal furniture, and leaving the corpse almost naked on the floor hastened away.

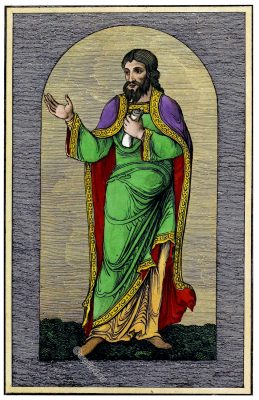

The state garments of kings at this period can be seen in Fig. 7. It is the type of dress worn by William I. as well as by other kings in Western Europe. The costume consists of at least five garments.

Under the mantle referred to below is worn the dalmatic-vestment of ecclesiastical significance forming part of his regal costume-with wide sleeves. Fig. 8 gives its shape. It is of silk, with an embroidered border of silk and gold decorating the edge, the sleeves, and round the neck. Sometimes a design was powdered, diaper-wise, over the whole garment. A narrow belt encircles the waist, often studded with gold and jewels, the width of the dalmatic being drawn in by it and slightly bulging over it.

The under-tunic is of rich material, and about the same length as the dalmatic-to just above the ankles. Under this again would be worn one, two or perhaps three under tunics or shertes (shertes: A tunic worn under other clothing).

The sherte worn by the nobility and wealthy upper classes at this period assumed the familiar shape of the shirt of modern times. It was cut straight and descended to the knees, having slits at the sides. Often the slits were at the front and back, and sometimes at the sides as well.

The sleeves were close, and reached to the wrists where they were frequently rucked. This garment was made of finely woven linen “chainsil “-and was invariably white. The Norman nobility set the vogue of ornamenting it by colored stitching to form a substantial neckband. This stitching was repeated at the wrists.

Worn as an occasional additional luxury, and for warmth, a garment of silk or wool was sometimes used over the sherte, and beneath the under-tunic: it was shaped like the sherte, save that the sleeves very often only came to the elbows. When used by the best-dressed people, it was decorated at the edges with needlework.

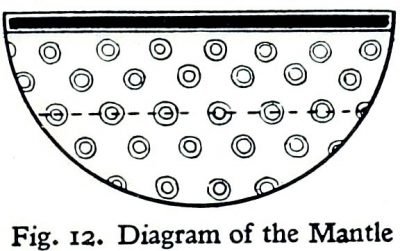

Among the French this garment was known as the JUBE and the blouse worn to-day by the French working-class is its lineal descendant. Over the king’s shoulders is draped the semicircular or rectangular cloke, now called in Norman French the “Manteau” or MANTLE. It has an embroidered or gold border, and this garment, like the dalmatic, could have a pattern dispersed over its area. The mantle could be fastened in front, or on the right shoulder, with a clasp or fibula, or tied with cords having metal ornaments at their extremities.

William wears a crown (see Fig. 7) on full State occasions, as he did notably at the three great feasts: Easter at Winchester, Pentecost at Westminster, and Christmas at Gloucester. The legs are clothed with hose, or, as they were sometimes called in Norman French, CHAUSSES. They are made of cloth, linen, cotton or silk, and often knitted. The shoes are described under Footgear.

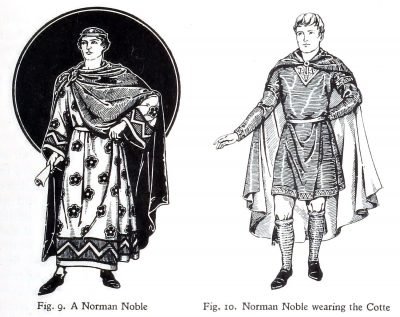

Fig. 9 represents a Norman noble who is dressed in a somewhat similar style. Here the wide-sleeved tunic has a design worked over its surface, in addition to borders at the edge and on the sleeves.

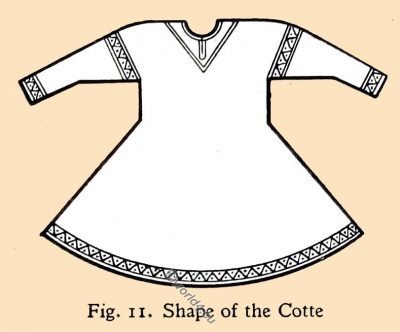

About this time the tunic received various names in the Norman French language. When short it was called the COTTE; when long, the ROBE; and a little later, when the tunic became a super tunic – the SURCOTE. Fig. 10 shows a Norman noble in everyday dress, wearing the cotte. Its shape is seen in Fig. 11. It should be noticed that the lines on the shoulder and arm are at different angles from those of preceding diagrams of tunics: this arrangement necessitated either two seams to the sleeve, or joining by a seam to the shoulder, often masked by a band of embroidery. The semicircular mantle in this example is worn fastened in front.

On the legs braies are worn, and over them hose, which appear to be knitted. They are tied below the knees by GARTERS with fringed ends, and the tops of the hose are rolled down over them. This type of leg-covering appears many times in the Bayeux Tapestry.

Nobility- Women

Matilda of Flanders, born 1031 (About the birth of Mathilde neither the place nor the date have survived.), was the daughter of Baldwin V., Count of Flanders, and a descendant of AElfred the Great. She was married in 1049 to William, Duke of Normandy (William the Conqueror), in the Abbey Church of Notre Dame d’Eu. Crowned Queen of England 1068.

It has been said of her that she was very fair and graceful, uniting beauty with gentle breeding, and possessing purity of mind and manners. Magnificent and liberal in her gifts, she greatly encouraged the Arts-architecture, painting, embroidery, literature and poetry.

Matilda was the first queen of England to sign herself “Regina,” although Anglo-Saxon historians, who wrote in Latin, used the word “Regina” in order to avoid introducing so barbarous a word as “Quen” into the Latin text: the king’s wife had been known prior to Matilda’s time as “The Lady his Companion,” or “Quen.”

Matilda of Flanders died 1083, and was buried between the choir and the altar of the Abbey Church of the Holy Trinity, Caen.

THE CHILDREN OF WILLIAM AND MATILDA.

- Robert Curthose, married Sybilla, whose son William, called “Clito” or Royal Heir, was slain at Alost 1128. Robert died in Cardiff Castle 1134.

- William Rufus.

- Henry Beauclerc.

- Cicelie, a nun of Holy Trinity, Caen.

- Constance, married Alan Fergan, Earl of Brittany.

- Alice or Eadwige, contracted to King Harold.

- Adela, married Stephen, Count of Blois, and was the mother of King Stephen and of Henry, Bishop of Winchester.

- Agatha, betrothed to Alphonso VI., King of Leon and afterwards of Castile.

It is said that “contemporary” painted portraits of William and Matilda were carefully preserved on the walls of S. Stephen’s, Caen, until destroyed by the Revolutionists at the close of the eighteenth century; but the copies which may be seen to-day, published in Montfaucon’s Monumens Monarchie Francois, prove them to be works of the thirteenth century.

Queen Matilda was dressed in a manner similar to all other great ladies of Western Europe, including the English. Only one new detail of feminine costume was introduced at this time – that was the girdle. In her will, in the register of the Abbey of the Holy Trinity at Caen, kept in the National Library in Paris, we have mention of some items of Matilda’s wardrobe:

“I give to the Abbey of the Holy Trinity my gown worked at Winchester by Alderet’s wife, and the mantle embroidered with gold which is in my chamber, to make a cope. Of my two golden girdles, I give that which is ornamented with emblems for the purpose of suspending the lamp before the great altar. I give my large candelabra, made at S. Lo, my crown, my sceptre, my cups in their cases, another cup made in England, with all my horse trappings, and all my vessels, except those which I may have already disposed of in my lifetime; and lastly I give my lands of Quetchou in Cotentin (Normandy), with two dwellings in England. And I have made all these bequests with the consent of my husband.“

It will be seen from this will that the queen greatly valued her gown worked by Alderet’s wife, an Anglo-Saxon woman. The royal mantle embroidered with jewels worn by her at her marriage, and probably at her coronation, was kept in the treasury at the Cathedral of Bayeux. It is mentioned in an inventory, dated 1476, of precious effects belonging to that church.

Plate I. (frontispiece) represents Queen Matilda, and is founded on this evidence and details derived from other sources. The gown, cut on the plan of the Anglo-Saxon, is of fine cloth or silk, embroidered in vermilion and gold “by Alderet’s wife.”

It has close sleeves to the wrist, where they finish with a band of similar embroidery; the neck is outlined with the same. The waist is slightly drawn in, and loosely encircling the figure is the girdle, a new article of attire introduced into England at this time. Girdles were made of strands of cord, in gold, silver, or colored wool, kept together at intervals by metal ornaments, jeweled, or set with enamels and jewels. These ornaments sometimes had emblems upon them.

The strands of gold or wool were often connected by knots or twists of wool or gold thread, the loose ends forming tassels. These girdles were generally worn double, with the tasseled ends passing through the looped end at the front.

Alternatively, the girdle might be composed of a strip of cloth, possibly stitched with a different color. More elaborate ones would be made of a twist of silk, plaited with gold. Plate I. shows a gold girdle, strung with gold and enamel ornaments.

The mantle of blue cloth, cut in a semicircle, Fig. 12, has a rich border of crimson embroidered in gold; it is lined with another color, and fastened across the shoulders by cords connecting circular ornaments.

The undergarments of wealthy women consisted of an under-gown, made of rich material, and cut like the over one except that it would not be so full in the skirt part. When the over-gown had close sleeves it is very probable the under one was without them. Under this again another gown, called in Norman French the “Camise,” (from Arabic qamīs, from Late Latin camisia) was worn, and possibly a second camise under this.

The veil in Plate 1 is rectangular, made of very soft, floating material, chainsil, gauze, etc.-embroidered with gold. The crown and scepter are made of gold, and simple in design.

Fig. 13 shows a noble lady of this reign. Her gown is similar to the one just described.

Norman and English ladies wore a long undergarment to the feet. If worn with a wide-sleeved over-robe, the under one would have tight sleeves rucked at the wrists. The overgarment would be of the same length, and both were cut to fit a little more closely than hitherto round the waist and bust, the skirts widening out towards the hem. The sleeves to the overgarment might be close or wide. Its shape is the same as shown under Anglo-Saxon costume.

The Norman or Old French name for this garment was “robe.” This drawing shows the embroidery ornamenting the neck, wrists and upper arm. The last was placed at the edge of, or over, the seam which joined the sleeve to the body part, a seam having become necessary now that the body part fitted closer to the armpit. This lady is wearing a girdle of silk twisted with gold. A mantle would be worn for full dress, attached across the shoulders with cords, while to complete the costume a circular veil would be worn, surmounted by a fillet.

On the head, and round the neck, it was the custom to drape a circular, semicircular, or oblong veil of some soft material, always colored, and often embroidered. The head cloth or headdress was called COUVRE-CHEF by the Normans, the origin of our “kerchief.” It was also made of fine linen or cambric, draped over the head, and hanging on each side of the face. If the veil was a rectangle, one of the ends, more often than not the right, was thrown over the opposite shoulder, and had almost the same effect as the Anglo-Saxon circular veil. The circular veil with a hole for the face cut in its area became obsolete.

The Camise or Chemise (Norman French)

(Smock, Anglo-Saxon.) An undergarment falling to the feet or ankles, with close-fitting sleeves, cut on the same lines as the gown. It was generally worn next to the skin. Mention of this garment in its simpler form has been made from time to time, but it became more complicated towards the end of the eleventh century.

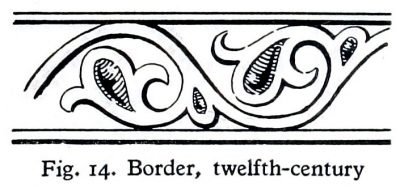

Fig. 14. Border of Chemise, twelfth-century

The part that covered the shoulders was gathered into a gauging, run on small cords or braids in several rows. This composed the neckband, which usually continued a little way down on to the chest. At the throat it was secured by a button and cord loop.

This neck band was frequently decorated with stitching in colors or gold, and often showed above the neck of the gown. The sleeves were finished off in the same way at the wrists, and on the forearm the full material was gauffered so that the sleeve clung close to the arm. A camise of the first half of the twelfth century is shown in Fig. 71: attention is called to the yoke on the shoulder.

The camise was made of various materials: fine wool, linen-particularly chainsil, or silk, when worn by the wealthy and upper classes. The middle and lower classes wore the camise of wool or linen material of inferior make, with less elaborate decoration.

MIDDLE AND LOWER CLASSES

Temp. William I. 1066-1087

Men. As regards the English of this period, the principal article of dress was, as usual, the tunic or cotte. These tunics were cut either moderately tight-fitting round the body, or loose, with the skirt part cut on the circle or square, and closed or slit up the sides.

The sleeves were either wide, showing the close sleeve of the sherte or the bare arm, or else close-fitting. The neck was a little more open than was usual before the Conquest; and sometimes slit downwards in front for about four or six inches, to show the neckband of the sherte.

It was usual to finish the neck, sleeves, and the edge of the tunic with a band of conventional embroidery in coloured stitching in wool, or with a band of different-coloured cloth, according to the position and means of the wearer.

The tunic was confined at the waist by a belt of leather, cord, or roll of material, and if the tunic was full enough it bulged over the belt. When the tight tunic was worn, it was not uncommon to leave it ungirded, as of yore; the tunic was then pulled in rather tight at the waist.

Under the tunic was worn the sherte or short garment, now common to all classes of both, sexes. When worn by women it was longer and called the camise. The lower classes had shertes and camises made of coarse linen in its natural hue. They fitted loosely, and had close sleeves rucked at the wrists.

Clokes were short, and long, square, circular, or semicircular, and worn as before- fastened with a brooch, or a metal ring on the right shoulder through which a part of the cloke was pushed and tied in a knot. Sometimes they were fastened in front. To these clokes a hood would be attached for use in inclement weather.

On the legs they wore close-fitting braies of cloth, wool, or linen, with or without cross gartering. Alternatively, loose braies reaching up to the knees were either tied at the ankle and knee, or cross gartered with leather or coloured cloth. Often ropes made of straw were used for this purpose. Gaiters of cloth or wool were in common use among the lower classes.

Fig. 42 is taken from the Bayeux Tapestry, and represents an Englishman or Norman of middle class, wearing a costume of the foregoing description, except that his legs are clothed in hose, having some ornamental stitching round the leg.

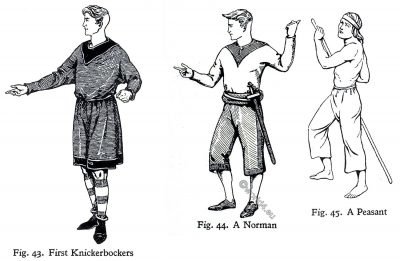

The artificers, workmen, shipbuilders, galleymen, stablemen, etc., brought over by William to assist in the disembarkation of his army, wore a useful garment consisting of a tunic with long sleeves and full KNICKERBOCKERS, with a belt round the waist.

These knickerbockers, in one piece with the tunic, descended to the knees, and cloth braies were worn on the lower part of the leg (Fig. 43). Often the knickers were separate, and worn with an ordinary sherte, the tails of which were tucked in at the waist. Knickers varied in shape; some were fairly full, suggesting a kilt; others were longer in the leg, but narrow, with a border down the outside of the leg and round the edge (Fig. 44).

There were also some very like football shorts; but in all cases the legs were covered with hose, striped round with different colours like football stockings, and in many cases crossgartered.

The knickerbockers had their origin in the long loose trousers worn by peasants living in England and in the centre of France, and much used by them during the course of the tenth, eleventh and twelfth centuries (Fig. 45).

There are curious examples of these long trousers worn by two figures of Welsh knights, carved upon the architraves of the south door of Kilpeck Church, Herefordshire (Fig. 46). (1) They wear Phrygian caps, close tunics that appear to be wadded, and trousers. Belts are knotted round their waists: one bears a sword, the other a mace. The present building was erected about 1134.

The lower classes usually went bare-headed, occasionally wearing a hood which came to a point at the top. When not in use this hood was thrown back on the shoulders.

(1) The parts of Herefordshire lying without Offa’s Dyke were regarded, until the reign of Henry VIII., as belonging to Wales.

HAIRDRESSING

Temp. William I. 1066-1087

Men. Many of the Norman gentry who accompanied Duke William on his expedition to England had their hair dressed in a very curious manner. The hair was allowed to grow to a moderate length on the top and in front, and was brushed forward. The back of the head was shaved, up to a horizontal line level with the tops of the ears.

Many examples are shown in a crude manner in the Bayeux Tapestry. Fig. 61 is a drawing derived from one of them (see also Figs. 43 and 44). We are told by Raoul Glaber (1 ) that the nobility of Aquitaine had been known for many generations before the Conquest for this extraordinary fashion.

This style of hairdressing was introduced into Northern France by the Aquitainian nobility in attendance on the Lady Constance, daughter of their earl, when she went to Paris in 998 to marry Robert the Pious. It originated, in a slightly different form, as far back as the 4th century, when it was in use among the early Franks.

(1) Historian of the eleventh century, born at the end of the tenth century, died at Cluny 1050.

As a contemporary fashion many Normans wore a natural head of hair, cut moderately short all round, as seen in Fig. 62 and Figs. 9 and 10. With the Normans it was the custom either to shave the face entirely or to shave the beard, except only so much of it as grew upon the upper lip.

To wear two locks of hair upon the upper lip (the moustache), without a beard upon the chin, was a fashion of the Normans (Northmen or Norsemen) from the time when they migrated to France in 912. They were worn very large and long, and the Norman-French name for these locks of hair was “guernons” or “gernons.”

Count Eustace of Boulogne had his upper lip decorated in this manner, and in consequence was surnamed “Aux-gernons.” He is represented in the Bayeux Tapestry, and Fig. 63 is drawn from this source.

A great friend of Duke William’s, Sir William de Percy, was also noted for his very beautiful gernons, and was nicknamed on this account “Alsgernon,” meaning William with the Locks. He was ancestor of the Dukes of Northumberland, and this name “Algernon” has been borne repeatedly by his posterity.

Closely cropped and shaven heads were abandoned by the Normans soon after they established themselves in this country, for a fashion in hairdressing of the opposite extreme.

When King William returned to Normandy in 1067 he was accompanied by many English nobles and prelates. Among these were Eadgar the Ætheling (d. 1120) (son of Eadward the Ætheling and grandson of Eadmund Ironside), brother of S. Margaret, Queen of Scotland, and heir of the royal line of Eustace of Boulogne English kings; Stigand, the ex-Archbishop of Canterbury; Fritheric, Abbat of St. Albans, and the Earls Eadwine, Morcar and Waltheof.

In the same company were some of the Norman nobles who had crossed the Channel with William only six months previously. They kept the feast of Easter at the Abbey of Holy Trinity, Fécamp, where a great number of bishops, abbats and local Norman and French nobles assembled. They looked with admiration and curiosity upon the long-yellow-haired English, and before long they were converted to this fashion of wearing long hair flowing on the shoulders, a change which soon spread over the whole of France.

FOOTGEAR

Temp. William I. 1066-1087

Footgear worn during the reign of William I. was quite normal, following the shape of the foot, as seen in the various drawings of figures under this reign.

High boots- pedules, and later, buskins formed part of the coronation equipment of emperors and kings of this and earlier times, a practice continued from Roman days, when official boots were the distinguishing mark of magistrates and patricians and, later, of the emperor.

They also formed part of ecclesiastical vestments from the sixth century onwards. Such footgear was made of silk and richly embroidered with gold and set with precious stones. They fastened up the front with ornaments, and when of a flexible nature were sometimes tied below the knee with tasseled strings.

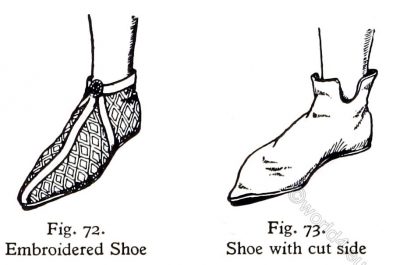

Shoes worn with State and full dress were very rich, made of colored leather, cloth or silk, ornamented with bands of gold. Sometimes the foundation was embroidered, chiefly in squares, lozenges or circles (Fig. 72). In some examples of this time the vamp takes a curved line over the top of the instep without any fastening, the foot being slipped in more easily in consequence (Figs. 10 and 44). In others it rises still higher to above the ankle, the top part being rolled over (Fig. 43). Occasionally this top part had a piece cut out at the sides to make it easier to draw on to the foot (Figs. 9 and 73).

Source:

- Costume & Fashion. The Evolution of European Dress through the Earlier Ages by Herbert Norris. Published 1924.

- A complete view of the dress and habits of the people of England by Joseph Strutt. London: H.G. Bohn, 1842.

- English costume painted & described by Dion Clayton Calthrop. Published by Adam & Charles Black. London 1907.

- The Connoisseur. Volume 9. London 1901.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.