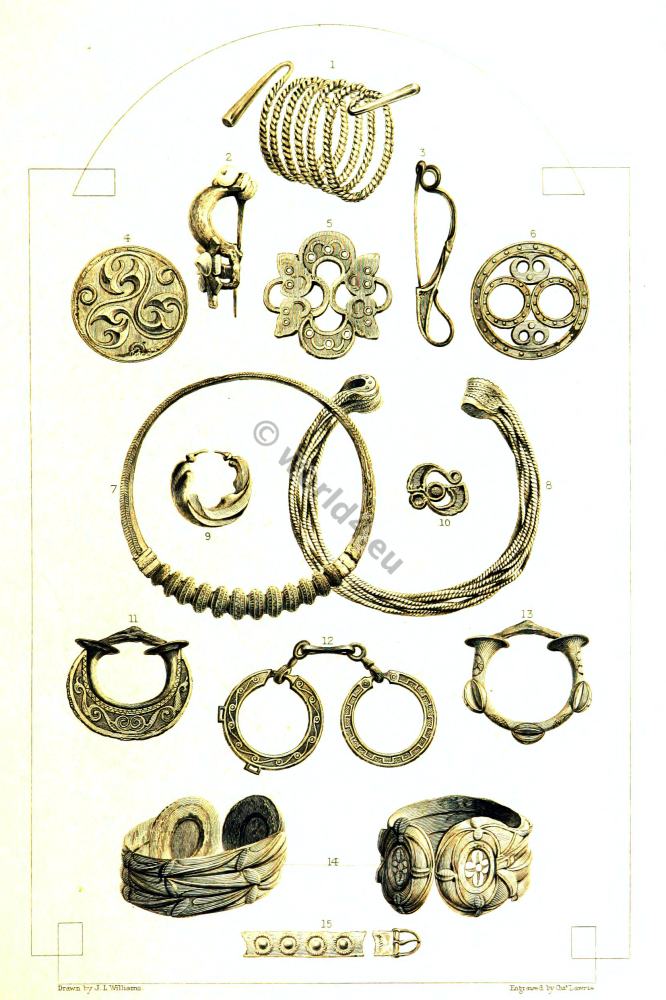

ANGLO-SAXON RELICS. PERSONAL ORNAMENTS, ETC., OF GOLD AND BRONZE.

- Enamelled Ring of King Æthelwulf ; in British Museum.

- Brooch set with garnets and enamelled, and enriched with filagree; found at Sarre, in Kent, and now in British Museum.

- 3, 3. Pins enriched with engraving; found in the river Witham, now in British Museum.

- Bronze Cross, the ornament in centre blue and white enamel, with gold mount; near Gravesend, now in British Museum.

- Gold Cross; found in Kent.

- Bronze Buckle, part gilt; found at Gilton, in Kent.

- Bronze Fibula; found at Badby, in Northamptonshire.

- Pendant of gold and enamel; in the Fausset Collection.

- Enamelled Pendant in the C. R. Smith Collection.5.

- Gold Ring; found at Bosington, Hants.

- Necklace; found at Sarre, in Kent, now in British Museum. The beads are of various colours white, yellow, green, amethyst, &c.; the pendant is beautifully enamelled, and the coins are of gold.

- Bronze Brooch, having four pearls and four wedge-shaped slices of garnet inlaid; found in a tumulus near Canterbury.

- Gold and Enamelled Brooch; found in Kent.

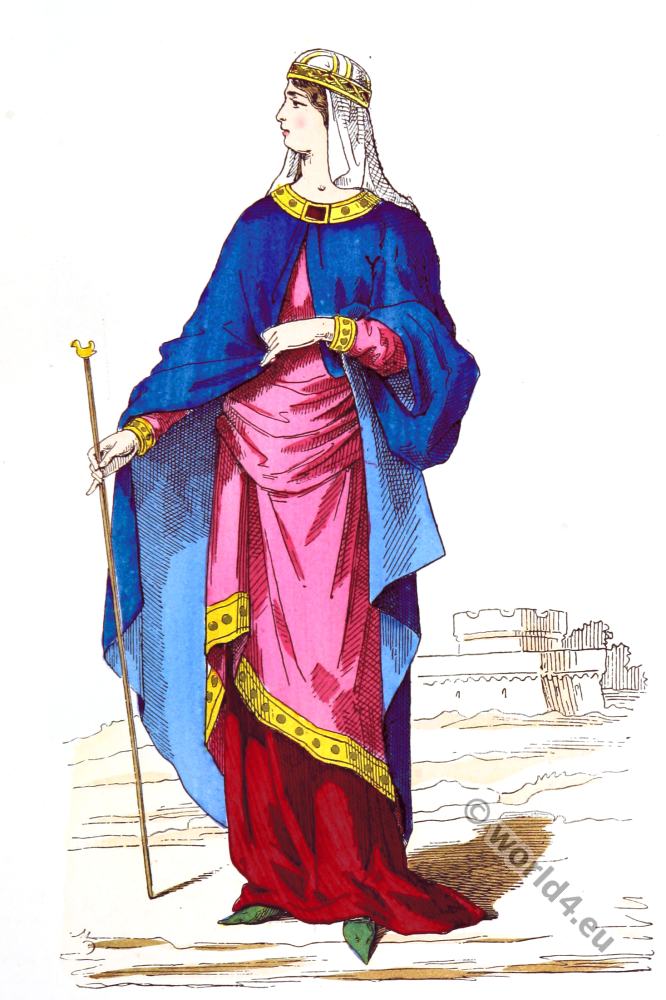

ANGLO-SAXON DRESS AND ORNAMENTS.

The great love of the Saxons and kindred races for display in dress and ornament led to a very, remarkable development of artistic skill in fashioning and decorating articles of jewelry, which were worn by men in greater profusion than by women.

There is no authentic record of the original costume of the Saxons on their invasion of Britain, but probably their dresses were so scanty as to need little description, and mainly consisted of coarse tunics, horse-hide leggings and jerkins, and barbarous ornaments. It is certain that the practice of tattooing the skin was not uncommon, and that both that and the maintenance of the barbarous costume was continued by some of the Anglo-Saxons as late as the latter part of the eighth century. But even at that time more luxurious and becoming apparel and choice ornaments had become general.

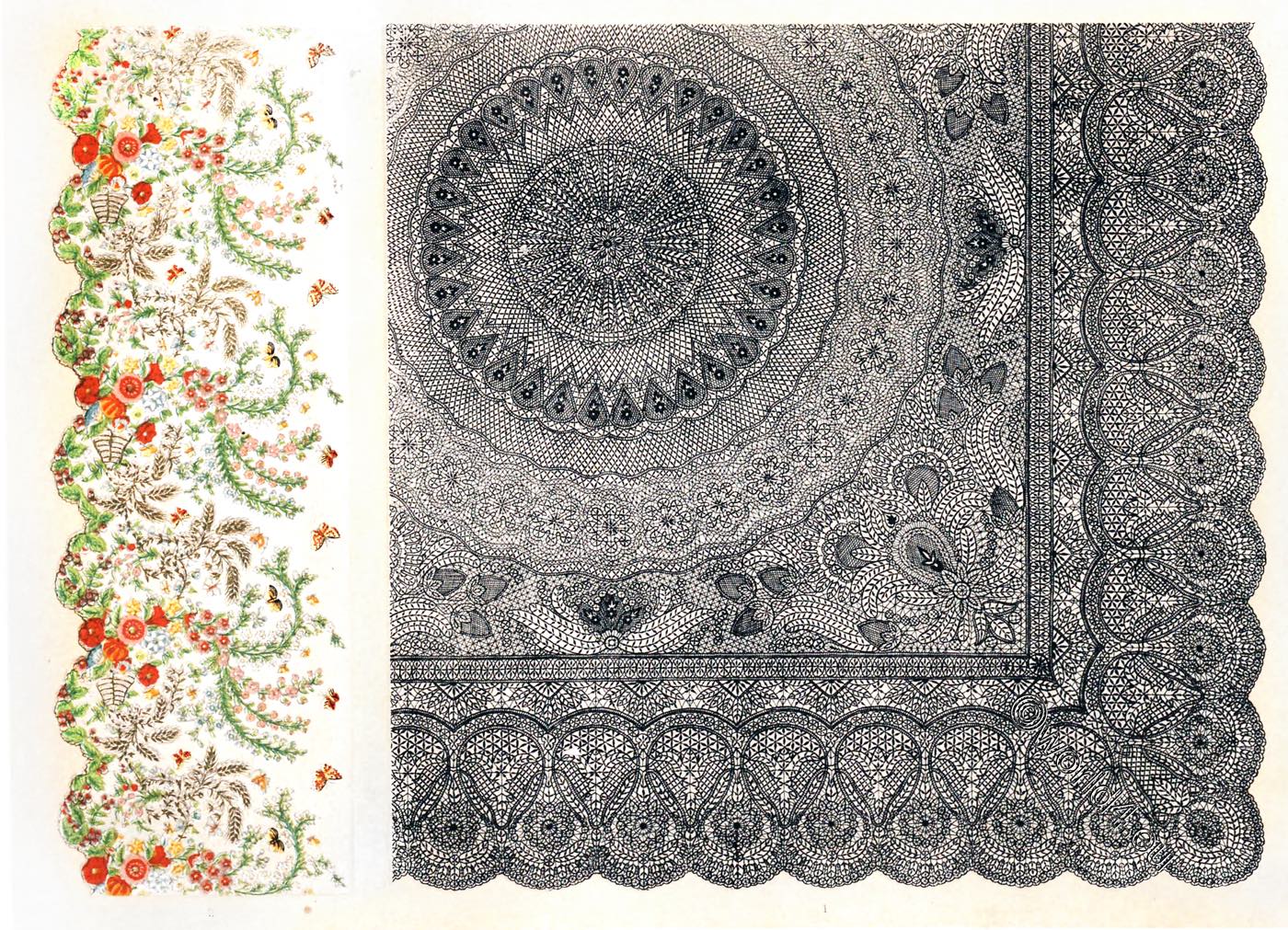

Of the Christianized Anglo-Saxons of that period Paulus Diaconus says:- “Their garments were loose and flowing, and chiefly made of linen adorned with broad borders, woven or embroidered with various colours.” This was doubtless the attire of the wealthy at that time, but we have very distinct accounts of the Anglo-Saxon costume at a later period; that is to say, in the time of Alfred the Great. There was little distinction in fashion between the garments of the nobles and those of the com- monalty, the distinction being in the material and texture.

Over a linen shirt they wore a tunic of linen or woollen descending to the knee, and open at the neck, and sometimes at the sides also. The sleeves of this garment reached to the wrists, and were either made to fit closely or were puckered into folds or creases. Occasionally the edges and the collars of these tunics were ornamented with needle-work, and it would appear to have been the original of the “smock-frock” of our agricultural population. 1)

The legs were encased in drawers or trousers which first reached no further than above theknee, but were afterwards made long like pantaloons and of one piece with stockings. These stockings were bandaged or cross gartered from ankle to knee with strips of coloured cloth or leather, while the shoes closely resembled those worn at the present day, and were fastened by two thongs, or thwangs.

Over the tunic was thrown a short cloak or mantle, gathered up and fastened at the breast or shoulder with a broach or a buckle. Nobles and distinguished persons substituted for this mantle a long tunic falling below the knee, and over it a surcoat with short wide sleeves and an aperture at top to admit the head. These were frequently of richly embroidered silk, and were lined with the fur of the beaver, sable, or fox. For high and low the covering of the head was a kind of Phrygian cap- but strangely enough this was usually worn in the house, while the long fair curly hair of which the Anglo-Saxons were so proud was considered to be sufficient protection in the open air in fine weather.

The relics of Anglo-Saxon jewelry and personal ornaments discovered in various places are so numerous as to enable us to estimate the artistic skill which was expended on such baubles, the work frequently consisting of ingenious involutions of knots and borders of a running pattern.

These ornaments consist chiefly of pins, buckles, fibulae or brooches, and necklaces, the latter being frequently composed of beads of very quaint device and fine colours. These beads are sometimes of various sizes and different degrees of opacity; some are banded, and others have projecting bosses or knobs of a different colour from the groundwork, the predominant hue being deep blue; but pale green, red, yellow, and brown tints are found both in the beads and their stripes or patterns, some of which form a kind of zigzag line, while the beads themselves are of all shapes, many of them being formed with facets, while others are made of a kind of coloured paste, and bear more elaborate designs.

The metal brooches or buckles were formed of gilded bronze as well as of the precious metals, and gems were occasionally set in them. The necklaces worn by women were occasionally of garnets, and finger rings were some of them formed like spirals, so that they closed on the finger. Hair-pins of great beauty of design have also been discovered.

It has already been mentioned that the nobles seemed more addicted to finery than their ladies, yet the dress of an Anglo-Saxon lady was particularly graceful, modest, and suggestive of dignity. The outer gunna, or gown, was a simple long tunic reaching nearly to the ground, and with wide sleeves falling to the elbows. It was mostly made of linen, and on the white ground the skill of the wearer could be exercised in order to enrich it with needle-work and embroidery in various colours and patterns. Over the gown a cloak or mantle was worn when the lady went abroad.

Beneath the gown was a more closely fitting tunic, with sleeves to the wrist, while the head-dress consisted of a veil or scarf of silk or linen, either wrapped round the head or fastened with a brooch at the forehead, and suffered to fall loosely about the neck and shoulders, the ends of it descending on each side as low as the knee.

Black shoes, and doubtless stockings of linen or woolen, completed the costume. The head-gear was sometimes confined by half-circles or fillets of gold; and ear-rings, necklaces, jewelled crosses, worn as lockets, and girdles, often richly set with gold or precious stones, formed the ornaments of a lady of distinction.

To great skill at needle-work and in the management of the household, the Saxon ladies frequently added considerable learning, and their purity of character added to the influence which they exercised, while at the same time the high position accorded to them in the social organization caused their fair fame to be protected.

In truth the Saxons had little to learn from the Normans with regard to that part of chivalry which concerns the vindication of the honour and reputation of the gentler sex. It is doubtless due to the influence and high education of the Saxon ladies that many of their lords were not debased by the pagan superstitions which lingered long after the establishment of Christianity.

Following the earnest instructions of Gregory, the early missionaries, instead of attempting to abolish the more innocent of the heathen observances and to forbid the keeping of certain festivals, associated them with some of the saints’ days or historical events of the church, or with monastic legends. Nowhere had there been so little change, in the names of days and festivals, and even now the days of our week retain the appellation taken from the old Scandinavian deities, while Easter, the great festival of the church, continued (it is said) to be so called from Eostre, the planet which represented the Venus or the Lucifer of ancient Rome.

1) Much interesting information on this subject is to be found in The Comprehensive History of England, by Charles Macfarlane and the Rev. Thomas Thomson.

Source: “Pictures and Royal Portraits illustrative of English and Scottish History. From the Introduction of Christianity to the Present time.” Author: Thomas Archer. Published in London, 1878 by Blackie & Son.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.