King Alfred’s Jewel, and the Ring of King Athelwulf.

FEW relics of antiquity are connected with more interesting historical associations than the jewel represented in our engraving. The inscription on the face, AELFRED MEE HEHT GEWYRLAN, i.e. “Alfred commanded me to be made,” and the circumstance of its having been found (about the close of the seventeenth century) in the isle of Athelney in Somersetshire, leave no room for doubting that it was lost by King Alfred in the lowest ebb of his changeful fortunes, when he took shelter in that spot from the pursuits of the Danes.

It was on this Occasion that the circumstance is pretended to have occurred which has been ever since so closely attached to Alfred’s memory, and of which the following account is given in an early Anglo-Saxon homily. “The King then went lurking through hedges and ways, through woods and fields, so that he through God’s guidance arrived safe at Athelney, and begged shelter in the house of a certain swain, and even diligently served him and his evil wife. It happened one day that this swain’s wife heated her oven, and the King sat thereby, warming himself by the fire, the family not knowing that he was the King. Then was the evil woman suddenly stirred up, and said to the King in angry mood, ‘Turn thou the loaves, that they burn not; for I see daily that thou art a great eater.’ He was quickly obedient to the evil woman, because he needs must.”

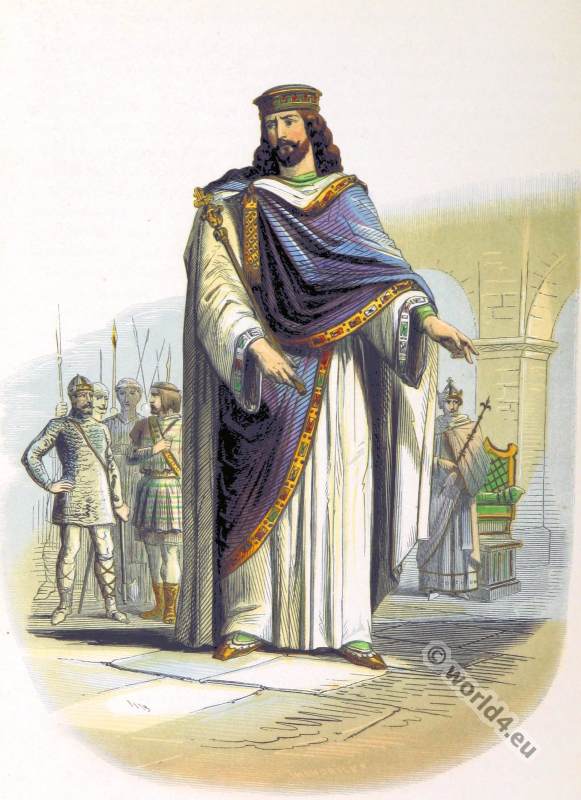

The Jewel which is connected so remarkably with this story, is now preserved in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. It is two inches and five eighths long, of gold, and containing within the inscription given above, a coloured vitreous paste representing, apparently, a male figure, holding in each hand what appears to be a sceptre (though probably only intended as ornaments), and covered with a crystal. Much unimportant discussion has arisen concerning the person thus represented. Round the outer edge is a purfled border of filligree work.

This remarkable ornament has been generally accounted to be an enamelled work, but it must be admitted that the rarity of existing specimens of so early a date is such, and our acquaintance with the processes of art employed at that period so limited, that the assertion can scarcely be made with confidence.

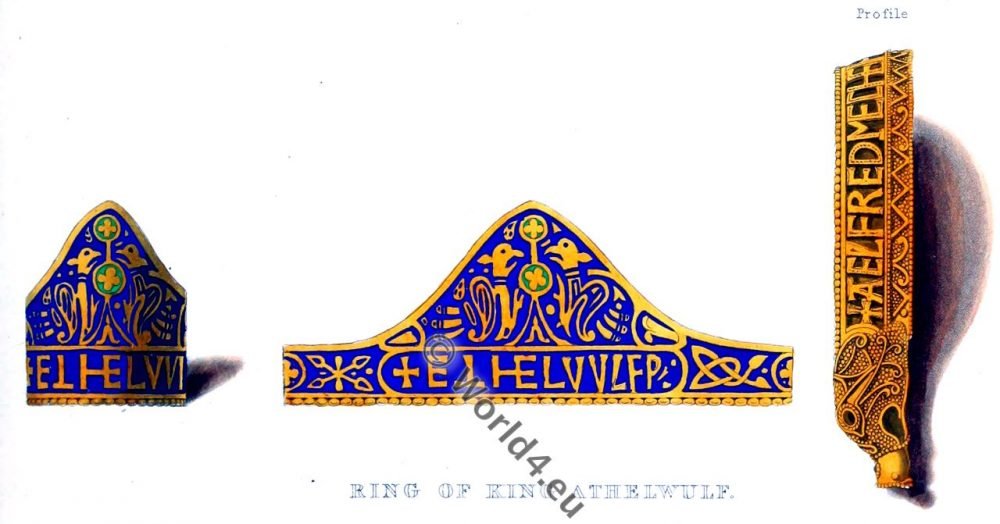

The most ancient specimen of what to all appearance is a true enamelled work is the ring of Athelwulf, the father of Alfred, preserved in the British Museum, and engraved on the accompanying plate. It exhibits the more ordinary process of the early enamellers, who chiselled out cavities on the face of the plate, to be filled by the fused pigment, leaving at intervals thin lines of metal, which, when the work was perfected, served as outlines to detach the variously coloured parts of the design.

In Alfred’s Jewel, and a very few other instances, this result is produced by thin disconnected fillets of metal, merely attached to the surface of the plate on which the colour is laid; and the coloured substance with which the lodgements thus formed are filled, seems to be rather a vitreous paste, than a true enamel. The comparison of a remarkable specimen recently discovered in London, and represented in Archaeologia, vol. xxix. pi. x. is in no small degree interesting; both are possibly productions of the artificers, whom Alfred is said to have brought to England.

The reverse of Alfred’s Jewel presents, on a matted ground, a kind of flower, with three branches; it is flat, and from that circumstance it has been concluded that the ornament was destined to be worn attached to a collar; but as the design would in that case have been seen reversed, some other intention must be sought, which, from our slender acquaintance with the personal ornaments of the Anglo-Saxon times, is not obvious.

Our initial letter is taken from a magnificent manuscript bible in Latin, and now preserved in the British Museum, MS. Additional. No. 10,546. It is a very large folio volume, consisting of four hundred and forty-nine leaves of extremely fine vellum, written in a beautiful and distinct minuscule letter, in double columns. It is embellished with four large paintings, and numerous richly ornamented initial letters. On the reverse of the last leaf are some Latin verses, stating that this noble volume was made under the superintendence of Alcuin, to be presented by him to Charlemagne:-

“Codicis istius quot sint in corpore sancto

Depictae formis litterulae variis

Mercedes habeat, Christo donante, per aevum

Is Carolus qui jam scribere jussit eum!

Haec dator aeternus cunctorum, Christe, bonorum

Munera de donis accipe sancta tuis,

Quae pater Albinus, devoto pectore supplex,

Nominis ad laudem obtulit ecce tui,

Quam tua perpetuis conservet dextra diebus,

Ut felix tecum vivat in arce poli.

Pro me, quisque legas versus, orare memento,

Alchuine dicor ego ; tu sine fine vale!

This Bible was bought by the British Museum in 1836 for the sum of seven hundred and fifty pounds. A full description and history of it by Sir Frederick Madden, will be found in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1836.

Source: Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages by Henry Shaw F.S.A. London William Pickering 1843.