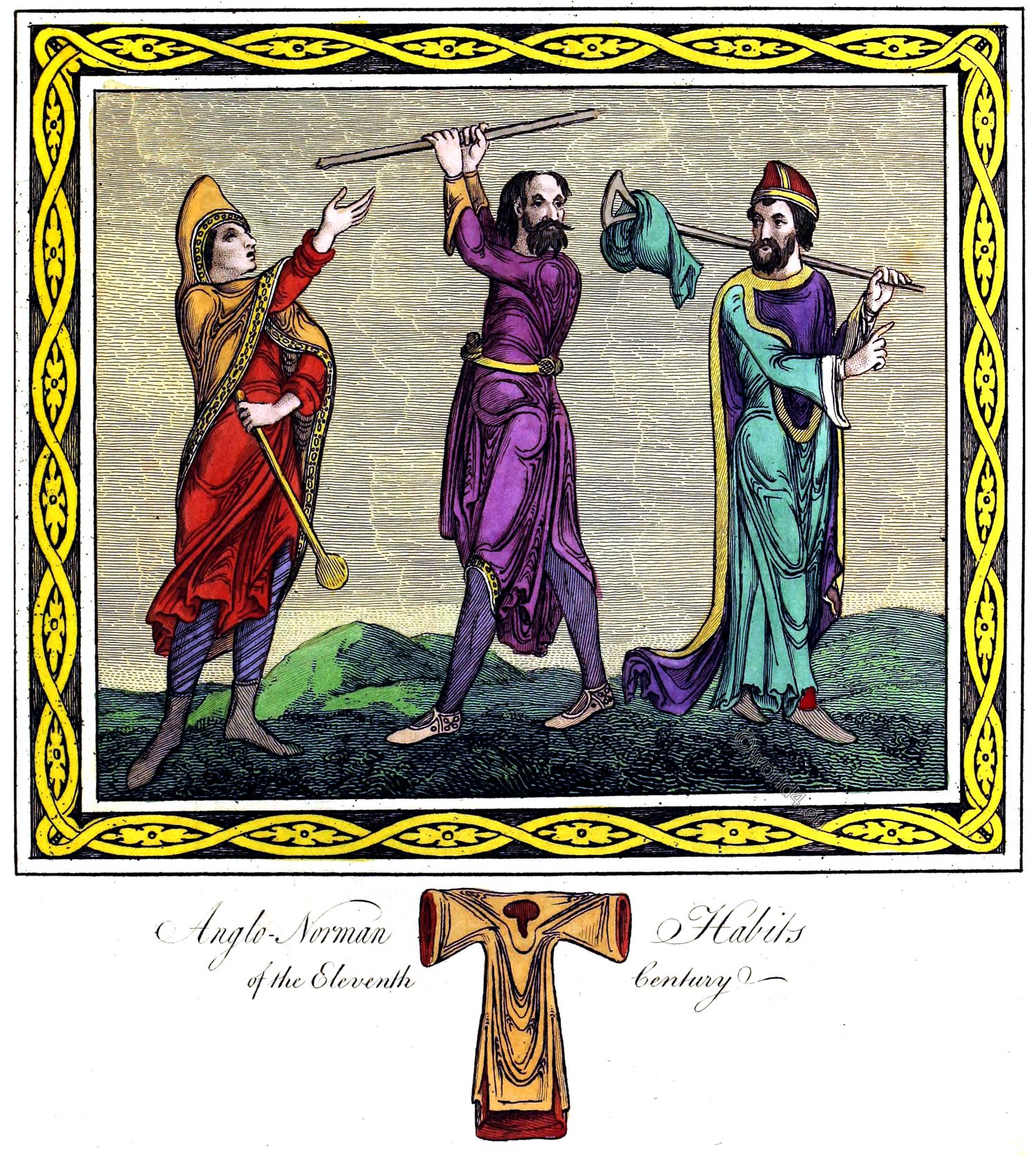

The dress of the Anglo-Saxon man.

Head-gear.— Banded Phrygian cap.

Cloak.— Of blue cloth embroidered.

Tunica.— Green cloth embroidered.

Stockings.— Red cloth cross-gartered yellow.

(Photographed direct from examples used in the Author’s lecture upon Mediaeval Costumes and Head-dresses.

The British Anglo-Saxon costume period, c. 460 to 1066.

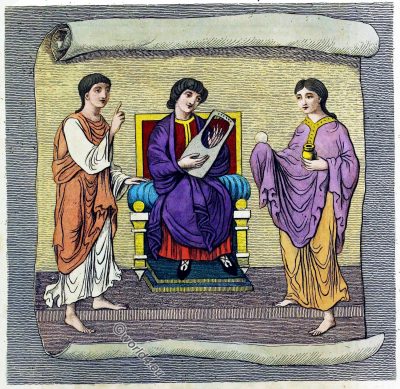

With the advent of this period we leave to a certain extent the region of conjecture, and enter within the bounds of certainty, inasmuch as the material for reconstructing the Saxon Period is of a much more tangible character than that afforded by the British. There are practically three authorities from which we derive information, namely, the Sagas, the contents of Saxon barrows, and the MSS. Unfortunately the Sagas deal as a rule with the heroic deeds of Scandinavian heroes, and although they furnish us with what may be termed minute details of military equipment, there are practically no references of any value to the civil or ecclesiastical garments of the men, or to the costume of the women.

The second source, the Saxon barrows, only affords us information concerning the gold, silver, and other ornaments, together with the military arms of our Saxon ancestors; and although this is valuable to a great extent, we have to rely finally for precise knowledge of dresses and decorations to the many priceless manuscripts which are preserved in the British Museum and elsewhere.

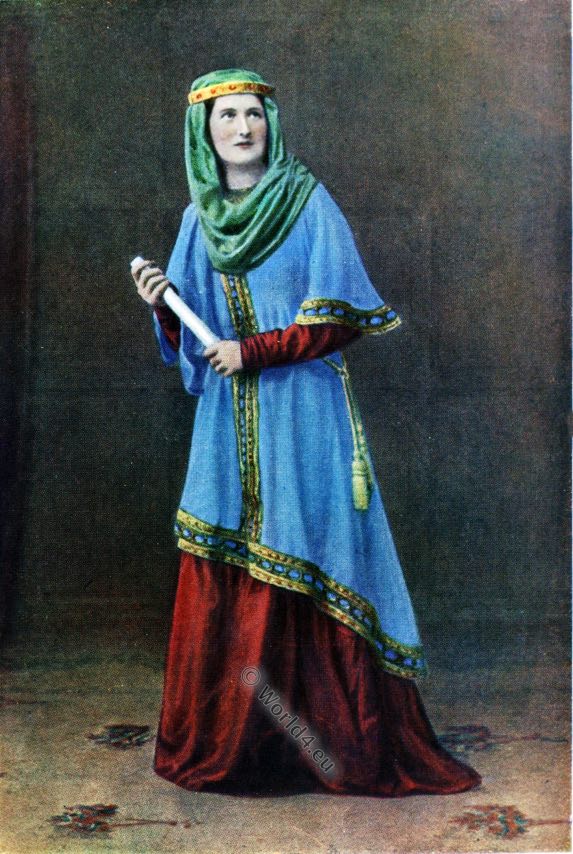

The dress of the Anglo-Saxon lady.

Head-rail.—Soft green silk with jewelled band.

Tunica.—Of blue woollen material, edged with embroidery.

Gunna.—Red cloth.

(Photographed direct from examples used in the Author’s lecture upon

” Mediaeval Costumes and Head-dresses.”)

The Anglo-Saxons commenced their conquests during the fifth century, but it was not until the year 720 that the earliest MS. preserved to us saw the light; there are consequently more than two centuries during which we have no reliable details. Spelman, in his “Councils,” refers to a meeting at the end of the eighth century, in which a speaker chides the Saxons for the manner in which they wore their dress, intimating that the nation had changed its style of clothing upon its conversion to Christianity. As a consequence, the description of the Saxon dress must be accepted as that which prevailed after the time of St. Augustine, and not to that worn before 597.

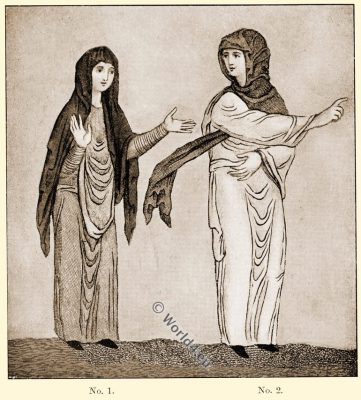

Saxon rustics.

No. 1. (Harl. MS. 603.) No. 2. (Cott, MS. Claudius B iv.) No. 3. (Bod. MS. Junius xi.)

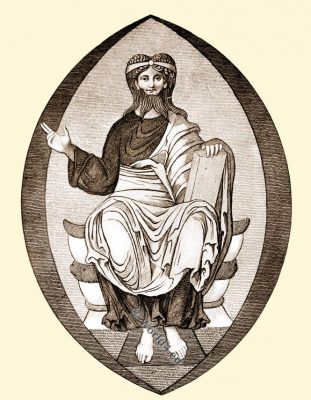

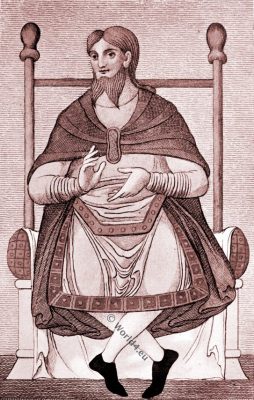

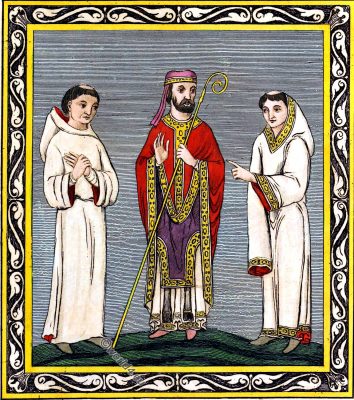

The Anglo-Saxon civil costume

Men dress

The garment worn next to the skin, or the justaucorps, appears to have been universal among all ranks, even to the humblest, who at times possessed no other clothing. For example, the Saxon rustic shown in Fig. 3, PL. No. 1, taken from Harl. MS. 603, dating from the reign of Harold II., is thus habited, and a still earlier example, No. 2, possesses but one garment. Of course it may be claimed that these figures are dressed in tunics. It was always made of linen, the wearing of a woollen garment next the skin being enjoined at that period as a severe penance.

No. 1. (Cott. MS. Claud. B iv.) No. 2. (Bod. MS. Junius xi.) No. 3. (Cott. Ms. Claud. B iv.)

The Tunica

This was of two kinds—the short, which was practically worn by all classes of people, and the long, which was generally considered as a mark of superior rank. The short tunica in the earlier period was simply provided with an opening for the passage of the head (Fig. 4, PL, No. 1), but in later examples it was open for a short distance from the neck, and laced up in front when adjusted, No. 2.

The sleeve was cut with the garment, having one seam only, and a very marked peculiarity of Saxon sleeves which may even be traced for nearly two centuries after the period, is the extraordinary rucking upon the forearm. This is explained by the fact that, during cold weather, the sleeves could be drawn over the hands to provide warmth. The hem reached to just below the knees, and subsequently became decorated with a worked border, which was carried up the two sides where the openings occurred, as in No. 3.

Around the waist a girdle was worn, seldom shown in the engravings, inasmuch as the tunica was pulled up through it, and fell in folds over it, giving the strange appearance which is such a marked feature of the waist. When indulging in very violent exercise, such as sword-play, throwing the lance, &c, more of the tunica worked up through the girdle on the right side than on the left, thus giving a slanting appearance to the hem. This striking point was promptly copied by the ladies (Fig. 21, PL).

The lavish ornamentation bestowed upon the garment in the later part of the period is indicated in No. 3. The tunica was not always cut up at the side. It is perfectly permissible to suppose that the smock-frock, or carter’s gown, of the present day, with its peculiar needlework, may be a direct descendant of the Saxon tunica.

The Mantle

Probably the most distinctive feature of the Saxons of both sexes was the mantle, flowing in graceful folds, and in sweeping curves of beauty. It was not always adjusted after a stereotyped fashion, but much was left to individual taste; the mode of fastening, however, was either in the centre of the chest, or upon one or both shoulders.

The shape of this mantle was that shown in Fig. 5, PL. No. 1; although plain in the earlier years, it finally became decorated (Fig. 6, PL). An example in which it is shown fastened upon the chest is given in Fig. 7, PL. where it is very voluminous; upon both shoulders in Fig. 5, PL. No. 2, and upon one shoulder in Fig. 9, PL.

Occasionally the mantle was made in a circular form, with a hole for the head not placed in the centre, as shown in Fig. 5, PL, No. 1. Upon comparing Fig. 5, PL, No. 4, which is of the eighth century, with No. 2, which dates from the tenth, it will be gleaned that the mantle eventually became much smaller; but this must not be taken as universal, inasmuch as persons of distinction and elderly people frequently wore mantles of great length, sometimes reaching the ground, over the long tunicas which they also affected.

The method of fastening the mantle was generally by means of fibulas or brooches, often of very elaborate workmanship, method used by the Druids for fastening the mantle had not fallen into disuse, we give an illustration from the Harl. MS. 603 (Fig. 8), where the mantle is distinctly seen to be pulled up through a ring on the right shoulder (see also Fig. 9, PL).

That the fastening was not always undone when it was removed is proved by an illustration in the above MS. representing the encounter between David and Goliath, in which David has thrown his mantle upon the ground still fastened with the brooch (Fig. 6, PL).

The Stockings

All Scandinavian nations wore short trousers reaching to mid-thigh, and the stockings of thin cloth were frequently made sufficiently long to join them; but the prevailing mode, and one which lasted for many years, was to wear short stockings reaching nearly to the knees, where they finished generally in the shape of the top part of a Hessian boot (Fig. 10, PL), but occasionally passed horizontally round the leg, and even at times downwards from the back.

Where no stockings are seen it invariably signifies that the long variety were used, the upper part not being visible. The exception to this was the rustic, who is very rarely shown with any stockings at all.

The Cross-Gartering

Like the Franks, Normans, and other Northern nations of Europe, the Saxons affected a style of cross-gartering which was often very elaborate. It consisted of strips of cloth of various colours, or, in the case of soldiers, strips of leather bound round the leg so as to form a pattern, and always terminating below the knee (Fig. 10, PL). In the case of persons of rank an ornament is sometimes shown at the knee (Fig. 11, PL).

The Shoes

The shoes of the Saxons [‘shoe’ and ‘thong’ are Saxon words] were of a simple character, and some had a series of openings across the instep.

Black half-boots turned over at the top and open from instep to toe; half-boots with double rows of studs from toe to top and round the ankle; and shoes of gold stuff with lattice-pattern embroidery were worn at court.

The general form of foot-gear was a low shoe, fastening up the front or the sides; occasionally a boot is shown, as in Fig. 12. The shoes appear to be universal, even the Saxon rustic being provided with them, although, as we have seen, he wore them without stockings.

The Caps

As a general rule the Saxons went bareheaded, but what may be termed the national covering was a cap of the Phrygian shape, made of leather or skin, with the hair outside in the case of the lower classes; and of cloth, more or less decorated with embroidery, among the upper. The same cap, strengthened with bands of steel, covered the head of the warrior. The pattern of this cap varied considerably, sometimes being high (Fig. 4, PL, No. 3), or low with a comb (Fig. 9, PI.).

A circular variety is shown upon a representation of King David. The members of the Witan and other personages of distinction affected a sugar-loaf cap, and we also find Saxon soldiers with a helmet of this shape (Fig. 9, PL).

Hair and beard

The Saxon men delighted in having long and flowing hair, in which they took a particular pride; only the very lowest classes had it cropped short. The beard was worn long and flowing, and a remarkable feature was the bifid form, which is so strongly emphasised in illuminations (Figs. 13 and 14, Pis.).

Although in many of these the beard and also the hair is rendered of a distinctly blue colour, it must not be imagined that a style prevailed for dyeing the hair, such a feature, if habitual, would certainly have been mentioned by contemporary writers.

Dress of the Anglo-Saxon Women

The Head-rail Head-dress to 1066

A remarkable feature of the costume of Anglo-Saxon ladies was the astonishing persistence of one particular style of dress over so many centuries. The earliest pictorial representation does not vary to any marked extent from the latest; practically the only alteration of any importance appears in the head-gear.

The Head-rail

This distinctive covering in the earlier form consisted of a piece of material—silk, cloth, or linen according to the social status of the wearer—which was approximately 2 1/2 yards in length and 3/4 yard wide. Its method of adjustment was to place one end of the rail loosely on the left shoulder, pass it over the head down to the right shoulder, under the chin, and round the back of the neck, and over the right shoulder again; the free end could either be left hanging loosely down in front, or the chest might be completely covered by taking one corner of the loose end and passing it over the left shoulder again (Fig. 15, PL).

A variation of this mode is perceived in the latter part of the period whereby the neck is exposed. In this case the rail was made only half its original length; the centre is placed upon the forehead and the two ends allowed to hang freely on either side (Fig. 15, PL). In order to keep the rail in position during gusty weather, and also perhaps for ornamentation, a narrow circlet seems to have been worn at times over it. An example of this occurs in Cott. MS. Vespasian A viii. (Fig. 16). The rail was of various colours, but apparently never white.

The Hair

Of the coiffure worn under the head-rail we have no illustration. The Bishop of Sherborne, who wrote in the eighth century, particularly mentions a woman having her twisted locks delicately curled by an iron; another is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon poem of “Judith” as having twisted locks; while from analogy with the continental nations, we may infer that they wore the hair in long plaits.

Among the jewellery mentioned in wills of that period, golden head-bands and half circlets occur, and from this one may gather that, although the head was always covered at home and abroad, the hair was by no means neglected. The term “fair-haired Saxons ” has led many astray when reproducing costume for female Saxon characters, and numerous examples have been seen upon the arenas of pageants of hair freely exposed. In the case of children this might be allowed, but certainly not with regard to adults. So rigorously is this rule enforced in all illuminations, that we have every right to suppose that it was a disgrace for a woman to appear in public with her head uncovered.

So deeply sensitive was the Saxon woman with regard to this rule, that, as may be seen in Fig. 17, from Cott. MS. Claudius B iv., they wore the rail even after they had retired to rest, and a similar example may be noticed in the interesting woodcut from the Saxon MS. of Caedmon (Fig. 18). There are examples, we may add, of women with their hair exposed, but they always represent questionable characters, such as public dancers, minstrels, &c. (Fig. 19).

The Kirtle

Respecting this garment we have no illustrations given; it was an article of dress corresponding to a combined petticoat and bodice of the present day. It is quite possible, however, that this garment is intended to be shown in the representation of the Virgin Mary in Cott. MS. Vesp. A viii., dating from 966, being a grant of privileges made by King Edgar to Winchester.

The Gunna

The gunna is seen looped up, and the kirtle, of a darker colour, appears underneath. It is quite open to argument, however, that these may be the gunna and tunica respectively.

Incidentally it may be mentioned that the ladies always rode side-saddle, as in the fashion shown in the accompanying sketch (Fig. 20) from Cott. MS. Claudius B iv.

(Cott. MS. Claudius B iv.)

The Gunna.-The English term “gown” is a direct derivative from this Saxon word. The garment was fairly tight-fitting, but long and flowing round the feet. It was furnished with tight sleeves, which were very long and puckered upon the forearm. In the earlier centuries the gunna was plain, and only ornamented by a band of embroidery round the hem, but in the tenth and eleventh centuries the material itself was at times covered with a design, often very elaborate.

The Tunica

This article of dress, which roughly corresponded with that worn by the men, was a very characteristic Saxon garment. The sleeves invariably reached to the elbows, and had large openings. The shape at the neck was probably like that of the man, being encircled with a piece of embroidery, the latter being carried down the front, where it joined another piece which passed round the hem. A girdle as a rule confined the waist. It will be noticed by reference to Fig. 21, PL, adapted from Harl. MS. 2908, that the marked peculiarity of the lower hem of the man’s tunic, in working up on the right side, has been faithfully imitated in the dress.

As this is the first example noted in this work of the imitation of features in the masculine dress by the ladies, we may say that it is of constant occurrence in all ages, and that we shall meet with many examples during the mediaeval and later periods. It is the fashion, which has almost become stereotyped at the present day, to complain of the ladies copying the dress of the men; but surely we may argue, that what has always been we should expect to prevail now, and there is no guarantee for its discontinuance in the future. After all, it is a compliment, for imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

The Mantle

This covering for the shoulders was made after the fashion of the ecclesiastical chasuble, but with more material in it, which gave it the graceful folds not seen in the priestly vestment (Fig. 21, PL). They were frequently very handsomely embroidered.

The Travelling Cloak was of varying designs, of which two may be seen in Fig. 22, taken from Cott. MS. Claudius B iv. The long sleeves of the lady on the right are for the same purpose as those upon the gunna, namely, to protect the hands during cold weather. The umbrella was not unknown to the Anglo-Saxons; it was of peculiar shape, as shown in Fig. 23.

The Shoes

These are but seldom seen in any illustrations, but when they do appear they are invariably black, and close-fitting.

The Danes

The advent of the Danes did not affect the Saxon dress to any appreciable extent. They wore garments of the same pattern, and it was only by the colours that they could be distinguished. We glean from Saxon writers that black was the prevailing hue. The short period which marked their stay in England is very deficient in authorities upon costume, but the references in Saxon writers to “the black Danes” leads us to suppose that it was their favourite colour. Certain it is that they sailed under the black banner, the raven being their emblem, as befitted Northern pirates; but no superstition was attached to the colour, as we find that soon after their conquests in England they became as gay in their clothing as their neighbours.

They were extremely proud of their long hair, which they regularly combed once a day; as this is related by a Saxon writer, we may infer that the latter was not quite so careful in his toilet. The hair of King Canute descended upon his shoulders, and that of many of his courtiers to their waists. The full-length figures of Canute and his Queen Alfgyfe (Ælfgifu) are reproduced from the manuscript Register of Hyde Abbey (Fig. 24); the only noteworthy feature with regard to the King is the way in which the mantle is fastened by a cord having two large pendants or tassels at the extremities.

This feature is also seen depending from the cloak of the lady, who wears a golden circlet, indicative of her rank, under the head-rail. The reign of Edward the Confessor witnessed the introduction into England of the Norman style of dress by many of those attending his court, and we know it to be one of the principal causes of the disaffection which prevailed throughout the country among the Saxon nobility.

This period also saw the introduction of new textiles and fresh designs, but the materials, which were essentially Saxon, consisted of linen, cloths of various textures, and silk, which was known to them as early as the eighth century. Their knowledge of embroidery was remarkable, and the figure given here, taken from the Benedictional of St. Ethelwold, must have been extremely beautiful (Fig. 25), for she wears an embroidered scarlet mantle over a gunna of gold tissue or cloth of gold.

The veil and shoes are also of the latter costly material. Appended are a few examples of the designs upon characteristic Saxon embroidery, with the sources from which they are obtained (Fig. 26). In order to demonstrate the passion for embroidery, Fig. 27 has been reproduced from MS. Tiberius C vi., which shows that not only did the upper classes make extensive use of this method of ornamentation, but they also permitted its use among their servitors.

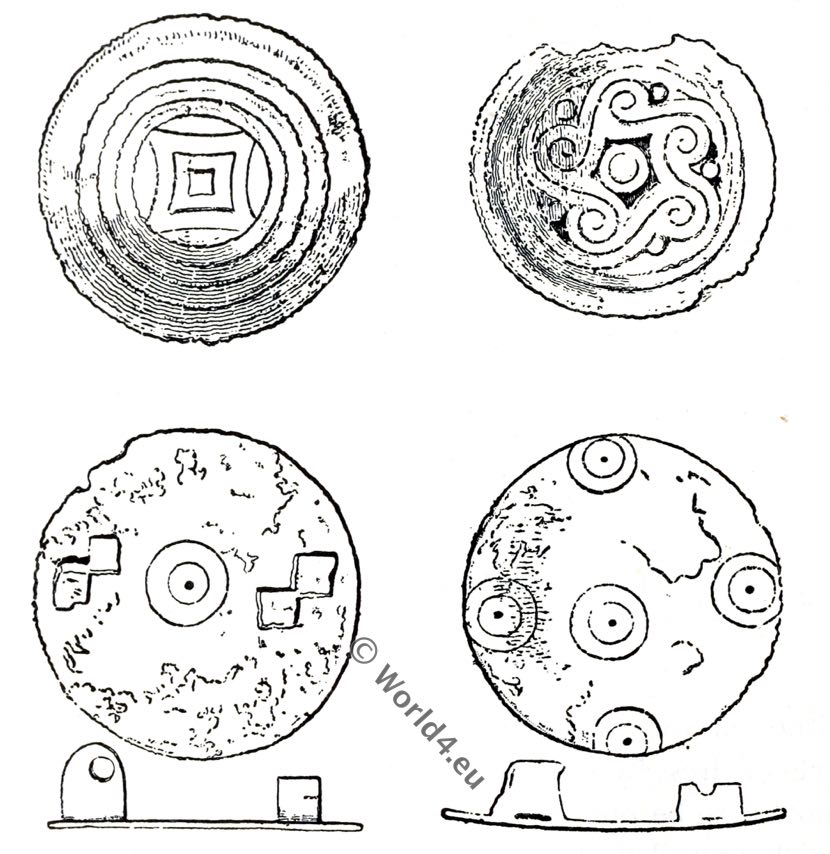

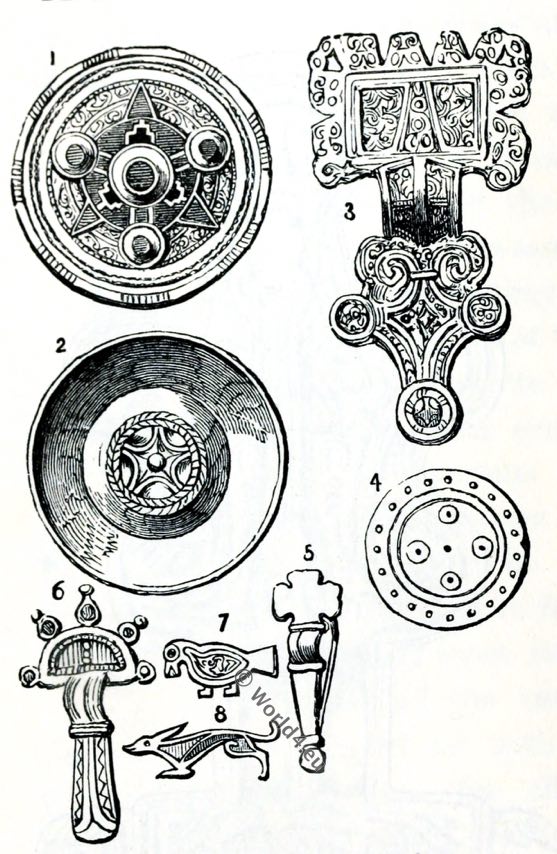

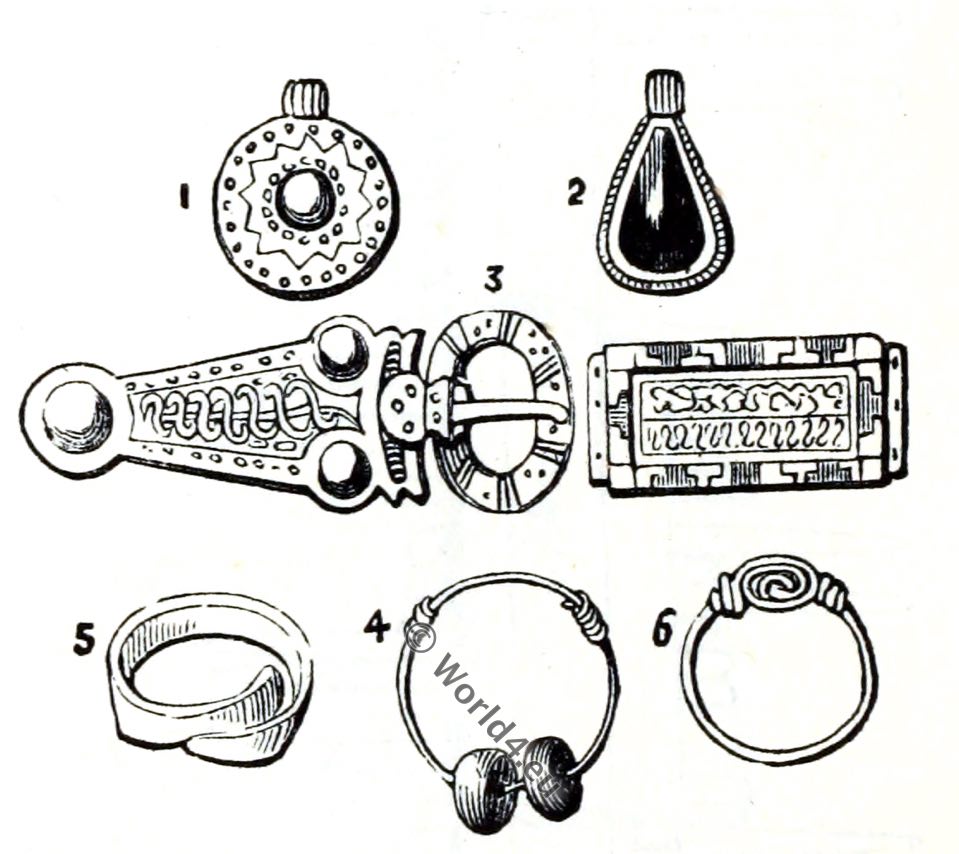

Saxon Ornaments, Jewlery

In the excavation of Saxon barrows many articles relating to the toilet and dress of both sexes have come to light, and there is hardly a museum in the country which does not contain examples. With such a wealth of material to hand, it is somewhat difficult to select specimens for illustration, but those found at a Saxon burying-place near Banbury are typical (Figs. 28, 29, 30) of the fibulae unearthed; they were generally disclosed in couples, each two corresponding to the right and left shoulders. They were mostly concave, and made of copper gilt, pure copper and brass.

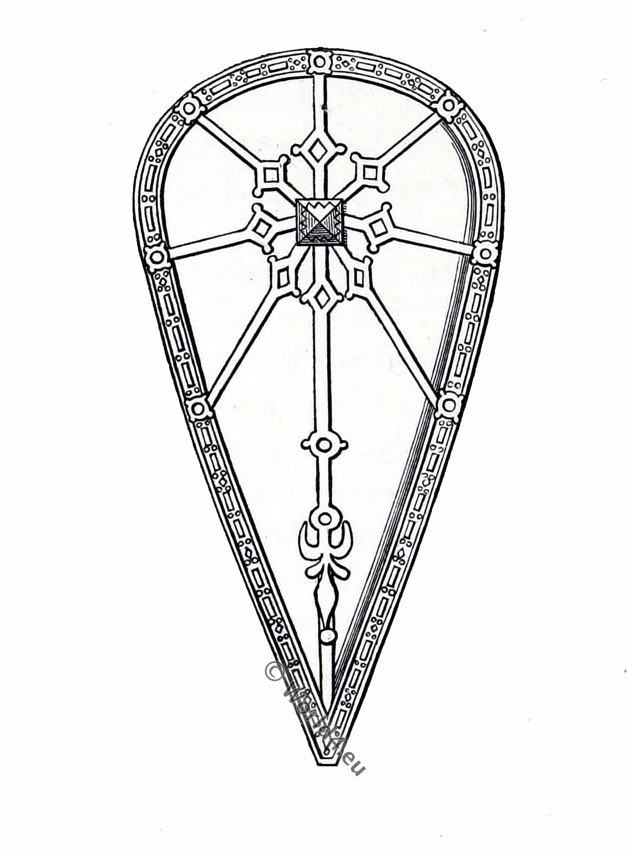

Anglo-Saxon shield 10th century

Fig. 28.—Saxon fibulae.

Fig. 29.—Saxon fibulae.

Fig. 32.—Saxon ring of silver wire.

Fig. 35.—Anglo-Saxon fibulae. 1 and 6. South Saxon. 2. South Midlands. 3 and 5. East Anglia and east part of Mercia. 4. Cambridgeshire. 7. Isle of Wight. 8. Roman.

Fig. 36.—Anglo-Saxon buckle, rings, and earrings.

The pin shown is of brass, and the ring made of silver wire (Figs. 31, 32). Two bracelets were discovered upon the arms of the skeleton of a woman, consisting of plates of metal which had been sewn on leather straps. Here also a comb was disinterred; it is of bone with iron rivets, and the teeth were apparently in the same condition when buried as they now appear (Fig. 33). Most of the skeletons had from four to twenty -six beads round the neck, of amber, glass, jet, various stones, and coloured clay, some with designs upon them. The most costly of the ornaments found are the fibulae, and some have been discovered of the most beautiful character, made of gold set with garnets and other stones, with pins for affixing them.

When it is remembered that the Saxon costume was essentially loose-fitting, the use of fibulae for fastening the various parts will be at once perceived, and as many as four or five of these brooches have been found in one grave (Fig. 34).

It is interesting to note that a Saxon lady was interred in full costume, with all her jewellery, no matter how costly, similarly to the warrior who was buried with his weapons, shield, &c. There are distinct characteristics pertaining to the fibulae found in various parts of the country. For instance, a circular fibula shaped like a small saucer is found in Oxfordshire and the adjacent counties (Fig. 35); it is always of brass and strongly gilt; in the Midland counties and East Anglia, bronze fibulas of the pattern shown in No. 3, a smaller kind, as in No. 6, comes from Kent, where No 1, of gold, garnets, and turquoise embedded in mother-of-pearl, was also unearthed, probably the finest ever found.

Pendent ornaments like earrings are sometimes discovered, together with buckles, rings, &c. (Fig. 36). Many Saxon ladies appear to have been buried with chatelaines hanging from the waist-belt, from which depended scissors, combs, tweezers, knives in decorated sheaths, keys, &c. ; and with purses also hanging from the same belt.

It was on this Occasion that the circumstance is pretended to have occurred which has been ever since so closely attached to Alfred’s memory, and of which the following account is given in an early Anglo-Saxon homily. “The King then went lurking through hedges and ways, through woods and fields, so that he through God’s guidance arrived safe at Athelney, and begged shelter in the house of a certain swain, and even diligently served him and his evil wife. It happened one day that this swain’s wife heated her oven, and the King sat thereby, warming himself by the fire, the family not knowing that he was the King. Then was the evil woman suddenly stirred up, and said to the King in angry mood, ‘Turn thou the loaves, that they burn not; for I see daily that thou art a great eater.’ He was quickly obedient to the evil woman, because he needs must.”

Charles H. Ashdown

Franks Bequest Catalogue of the Finger Rings.

Edward the Confessor giving his Ring to the Beggar. Subject of a thirteenth-century tile in the Chapter House at Westminster.

The more prominent episodes and events in which rings have played a part are matters of common knowledge. All have heard of Edward the Confessor’s ring given to a beggar, taken to Rome, and returned just before the King’s death, to be removed from his coffin in A.n. 1163 and kept at Westminster for the cure of epilepsy. The ring given by Queen Elizabeth to the Earl of Essex is even better known, and is said to be still in existence.

(Polydore Vergil, Hist. AngL. Bk. viii; J. Kirchmann, Dc annulis, p. 212; E. A. Freeman, History of the Norman Conquest, ii, p. 519; iii, p. 34; H. R. Luard, Lives of Edward the Confessor, 185S, pp. 276, 373.)

Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks

Source:

- British costume during XIX venturies (Civil and Ecclesiastical) by Mrs. Charles H. Ashdown. Published by Thomas Nelson and Sons LTD, London.

- Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages by Henry Shaw F.S.A. London William Pickering 1843.

- A complete view of the dress and habits of the people of England by Joseph Strutt. London: H.G. Bohn, 1842.

- Selections Of The Ancient Costume Of Great Britain And Ireland, from the 7th to the 16th Century by Charles Hamilton Smith. London 1814.

- Arts and Crafts in the Middle Ages By JULIA DE WOLF ADDISON, 1903

- Franks Bequest Catalogue of the Finger Rings by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, K.C.B., 1912.