ALEXANDRIA.

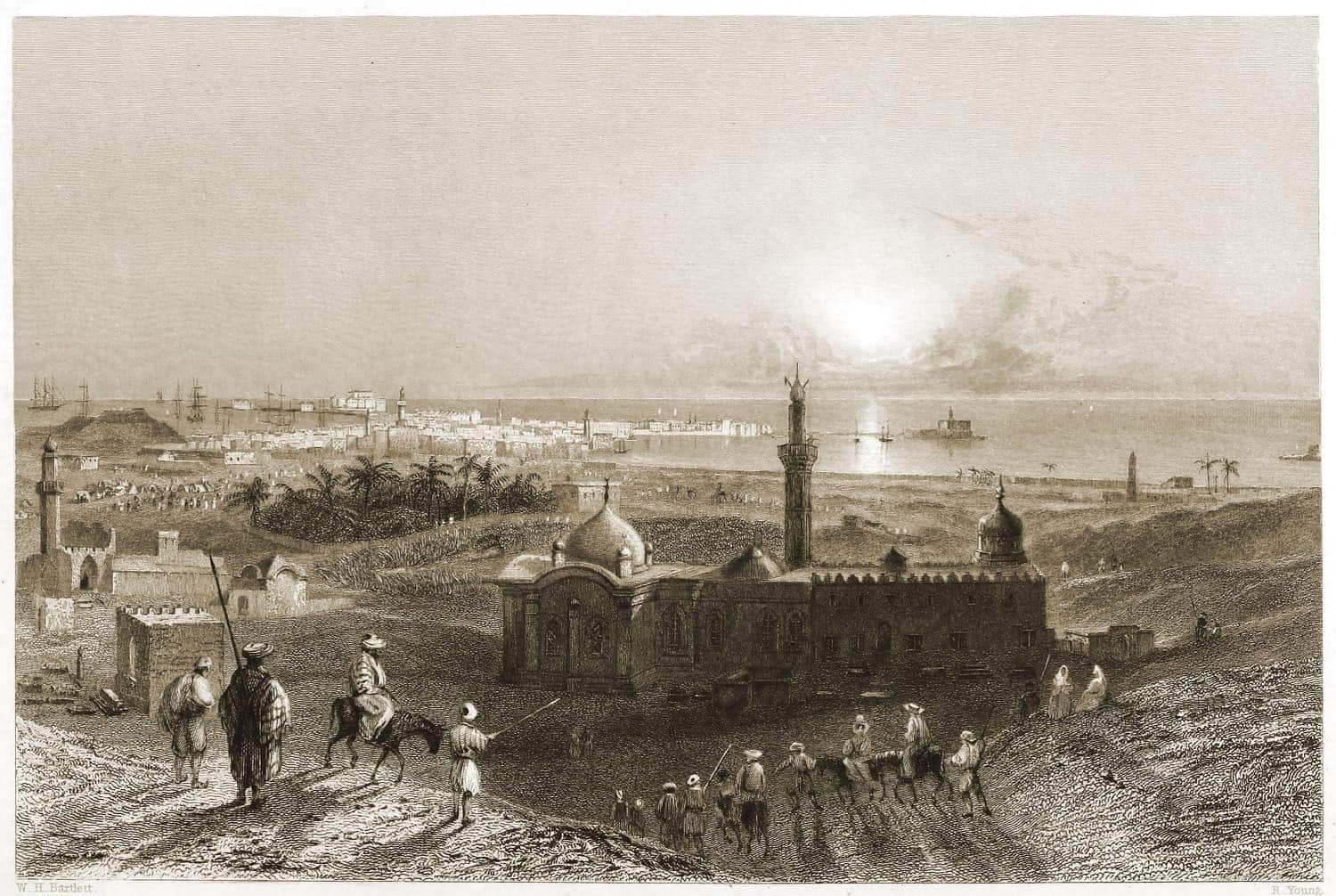

The sad town, and dreary vicinity, are seen to advantage in the lovely moonlight of Egypt. On the left, in the distance, is the large harbor, the men-of-war, and the palace of the pasha at the extremity, and the fort: to the right is the city, the dwellings of the consuls and merchants, the old harbor and its castle. The large building in front is a handsome mosque, erected by the pasha, and a tomb to receive hereafter his remains. The interest of this town is soon exhausted by the traveller, who in a few/days becomes weary of its dulness and desolation: not a single pleasant walk or ride without the gates, into the fiat, sandy, stripe of country, without trees or gardens. Its climate is not always the pure and brilliant one pictured by the fancy: even in June, the air on the banks of the canals is, in the morning, damp and foggy; in winter the rains are often heavy, the narrow and wretched streets full of pools, and unpaved.

A rainy day in Alexandria in December or January is one of the most disconsolate things in the world; the inmate of the inn looks out of his casement window, scarce knowing what to do with himself: shivering in the comfortless rooms and the sharp sea-winds, he sighs for his native fire-side, or for the sultriness of Egypt, which he will soon feel after leaving this town. After a Christmas dinner at the consul’s, the whole party, Spaniards, English, and Italians, were delighted to adjourn to another and smaller room, where a capital fire was blazing.

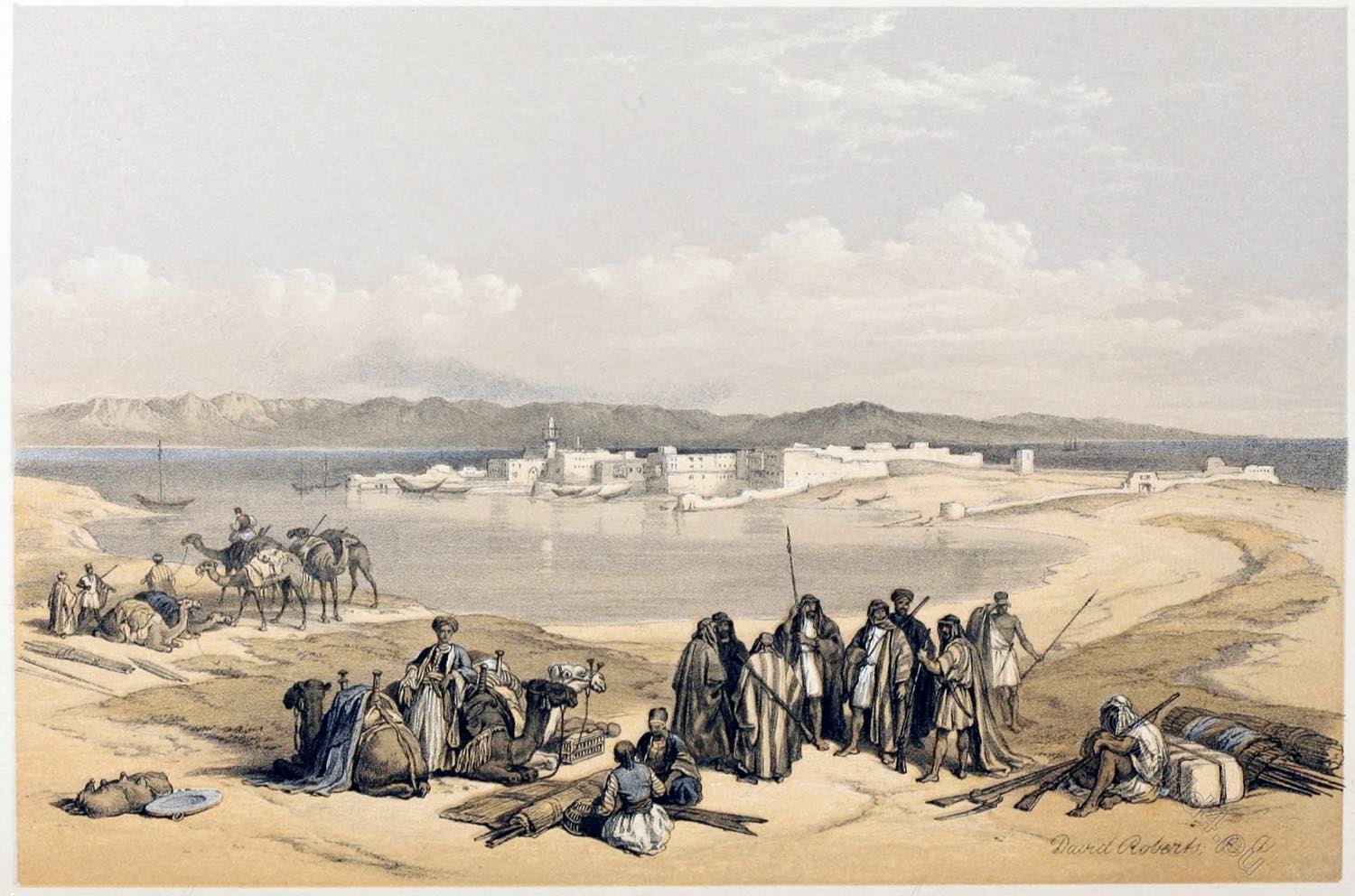

There is much commercial activity here, in striking contrast to the indolence and want of enterprise so apparent throughout Egypt: ranges of storehouses, bales of goods, and piles of timber, often cover the beach: the numerous shipping give life to the scene, vessels of various forms and dimensions, belonging to different nations; the pasha’s sloops of war and sail of the line, the large European merchantmen: the Oriental small craft, with their curiously shaped rigging; the trim-built Greek vessels of admirable construction; and the clumsy Syrian germs which regularly navigate this dangerous coast, and in one of which, embarking for Acre, we had a tedious and comfortless voyage. The customhouse and arsenal, which is never without a ship of war on the stocks, are not far from the principal landing-place of the new port.

The best, indeed the only good houses in the place, are those of the European consuls and merchants; the apartments are often spacious and even comfortable, and looking on the sea, which is the only pleasant and cheerful object. The quays of the two ports are in a great measure formed of the materials of old Alexandria. The mosques, the public warehouses, and even the private dwellings, contain fragments of granite, marble, and other stones, which clearly indicate that they once belonged to ancient edifices. In dry weather, full of dust, and of mud when it rains, the unpaved streets offer a wretched promenade; the houses of the native inhabitants present an entrance-door and a blank wall to the street, with now and then a huge projecting window above, so closely latticed, and its apertures so small, that the inmates seem to be immured in a gloomy prison.

Alexandria is a place of considerable trade, being the chief port by which the products of Egypt are exchanged for those of the various countries of Europe, most of whom have a consul resident here. In 1827, 605 ships entered the port, and rather more than that number cleared out. In the following year, there were about 900 arrivals, and rather less departures. The particular arrivals of the latter year will give a better idea of the trade of Alexandria: 293 Austrian, 136 English, 139 French, 102 Ionian Islands, 23 Russian, 110 Sardinian, 34 Tuscan, 15 Spanish, 13 Swedish, 14 Sicilian; and the departures of vessels of these various countries were nearly equal in number.

The markets are tolerable in this place; ordinary provisions are excellent in quality, and of moderate price; figs, apricots, mulberries, and bananas, very plentiful; also, ices every evening in the Italian coffee-houses, to which large cargoes of snow are annually imported from Candia. Wine is very dear, being all imported: even the Sicilian Marcella wine, that sells in Italy at a shilling a bottle, brings treble here and in Cairo.

The town has no fresh water; the inhabitants have recourse to the cisterns, which are filled partly by the winter rains, and partly by water brought from the canal (Mahmoudiyah Canal). This canal, called the new canal, the ancient one of Cleopatra, was restored and completed by the present pasha, at a great expense, and still greater loss of life: out of the 150,000 Arabs, by whose incessant labors it was finished, 20,000 died of fatigue. These poor men, taken from their homes in Upper Egypt, from their hamlets and villages, were cheerful and unrepining in the midst of their severe and protracted toils. The writer often saw them toiling in the bed of the canal, in a most sultry day, and allowed no cessation of labour, save during their meal at noon. They were a very great multitude; instead of plaints and murmurs, they beguiled their tasks by a kind of wild and plaintive chant. Their meals, while at work, consisted only of bread and water, and each man received the amount of a penny a day; but money, even this small sum, is valuable on the Nile.

This canal unites Alexandria with the Nile, and joins the Rosetta branch of the river at Foua: its length is about forty miles: it is navigable by boats of considerable size, but is already much injured by deposits of mud. It has totally ruined the trade of Rosetta, but has, in a measure, converted Alexandria into the metropolis of Egypt, and made it the seat of government, and the centre of commerce.

Donkeys are the only conveyance: they are the hackney-coaches of this town and of Cairo; for no native or stranger thinks of walking in Egypt: they are, more especially in the latter city, a handsome race of little animals, very superior in agility, as well as beauty, to their brethren of Europe. The population of Alexandria amounts to 35,000; of these, 3000 are English; Maltese and Ionians under English protection: about 500 French, Germans, Swiss, and other natives of the Levant, are under French protection; about 1,500 Greeks, Italians, Austrians, and Spaniards: making a total of nearly 5000 foreigners.

Divine service is regularly performed on Sundays in a suitable apartment under the consular roof, which is neatly fitted up; but out of the numerous body of English residents, not more than a dozen generally attend: the place is termed “The Protestant English chapel;” the service is performed by a resident missionary, who was a Wesleyan.

There are three inns; the two largest kept by Italians. English travelers will find at the establishment of Mrs. Hume, on the plan of a boarding-house, a comfort and cleanliness which are strangers at the inns. There is every effort to please, with excellent accommodations: hours of eating are fixed early, as they are in most of the European houses. The guest of the consul here and at Cairo must consent to dine, at first much against his will, soon after noon: at the most sultry hour of the day, the table is covered with a hospitable and substantial meal, for breakfast in Egypt is taken early and sparingly a cup of coffee and a little bread. The evening meal is taken, as throughout the East, after sunset.

Source: Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor illustrated in a series of views drawn from nature by John Carne, William Henry Bartlett, William Purser. Published by Fisher Sons & Co. London, Paris & America. c. 1836.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.