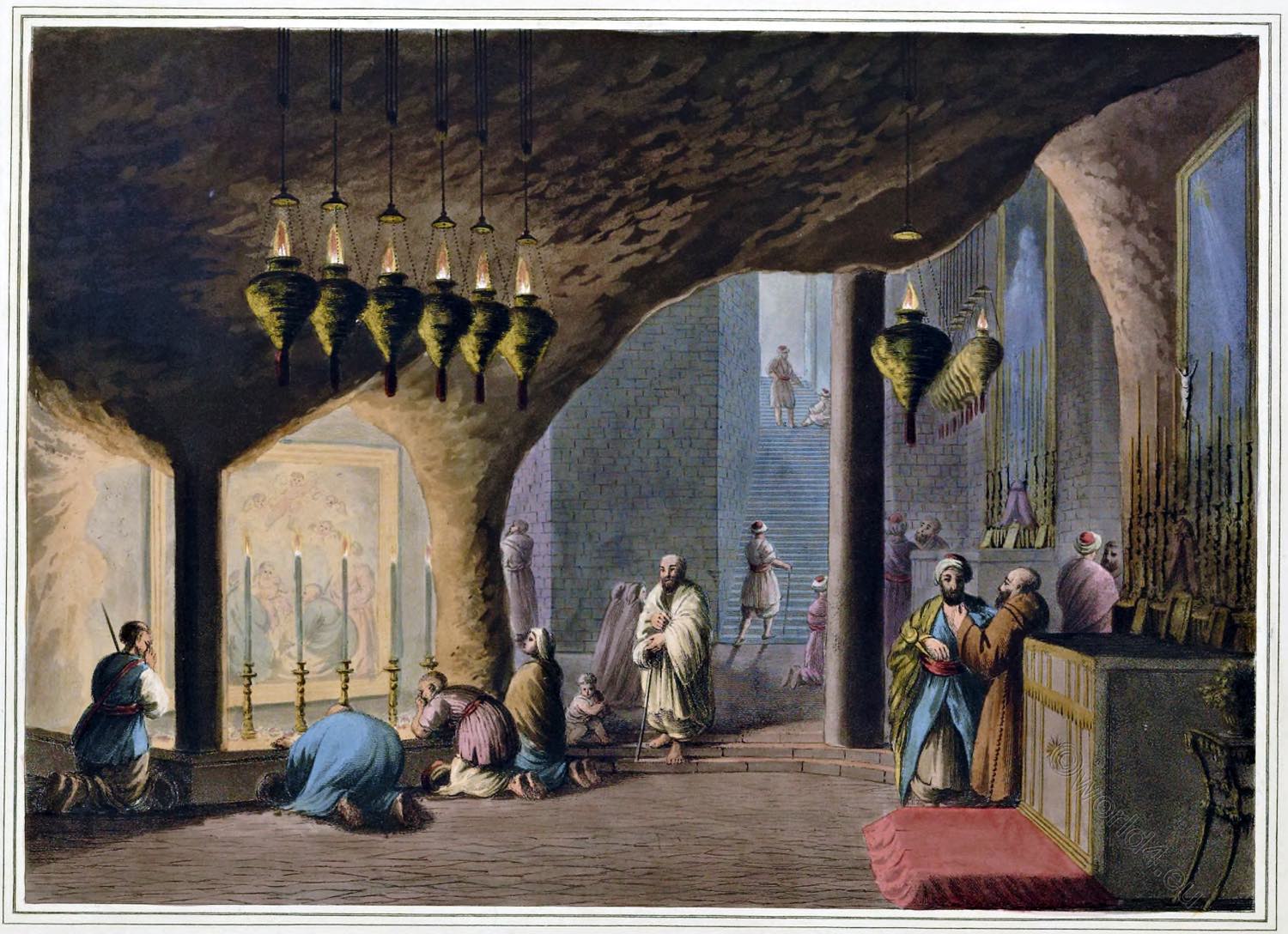

THE GREEK CHAPEL OF THE HOLY SEPULCHRE.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was nearly destroyed by fire in the year 1808; long neglected by the Latin Christians, it was repaired by Russia, which carefully cultivates its connexion with the Asiatic Greeks; and in consequence of this expenditure, the Greek monks have been put in possession of the most venerated parts of the edifice.

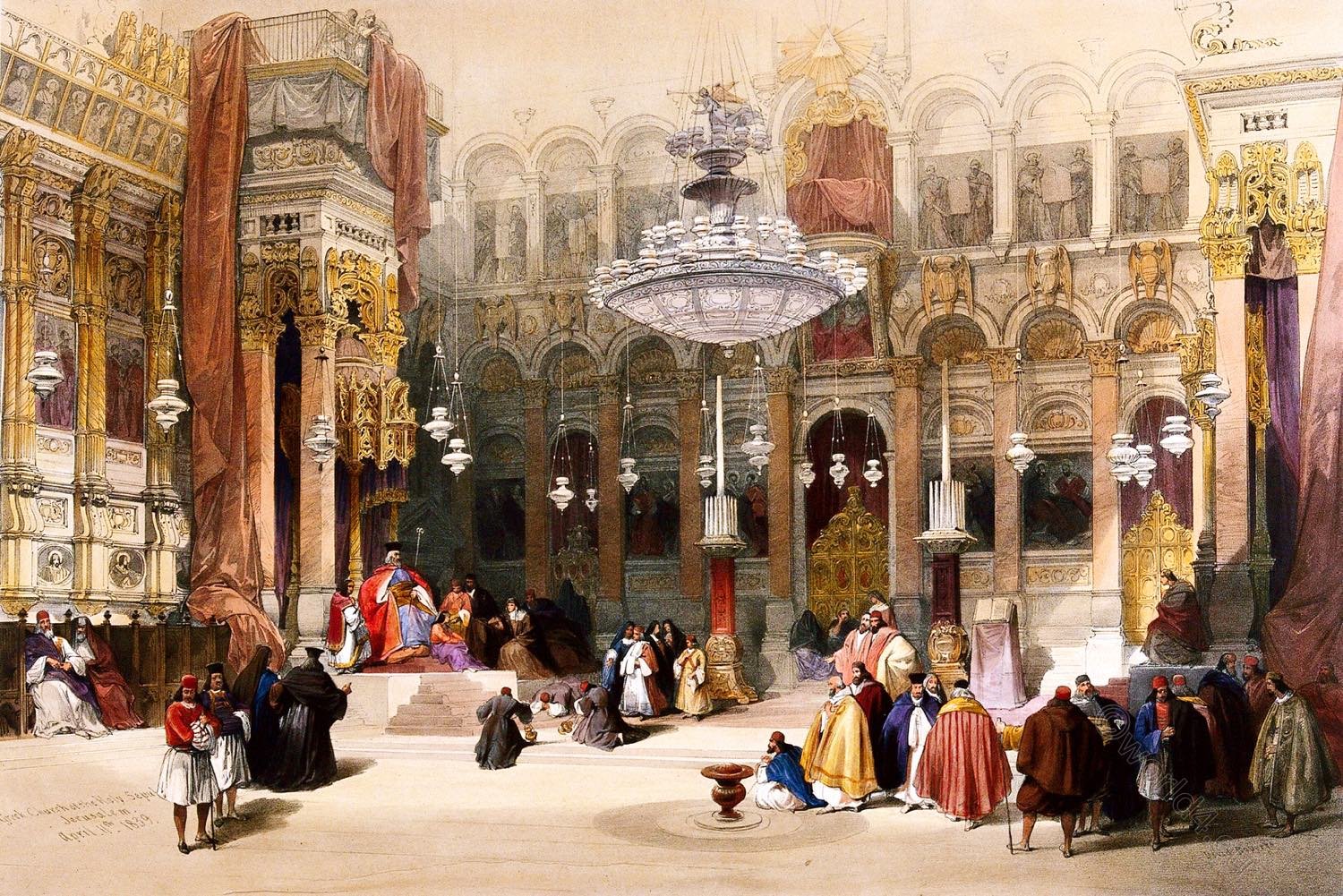

In the engraving the view is directed to the screen, which, as in all the churches of the Greek ritual, separates the nave from the altar. Though sculpture is rigidly excluded, pictures and other embellishments are largely employed. This chapel is lavishly ornamented; and though it exhibits a barbaric mixture of styles, Greek, Gothic, and Saracenic, the general effect is rich in the extreme. The profusion of gilding, the gold and silver lamps continually burning, and the elaborate decoration of every part, render the first view overpowering.

Near the centre stands a small vase, to which the Greeks attach great reverence, regarding it as the central spot of the earth, and call it the “Navel of the World.” Mr. Roberts’s Journal thus describes the scene as it met his own eye: “March 31, 1839 (Palm Sunday).— This is a great day at the Holy Sepulchre, and we witnessed the procession early in the morning. Perhaps after seeing the splendid sights of this kind in Spain, they were seen to disadvantage, still to me they were most interesting. The Latins took no part in the spectacle, being shut out on account of the plague, and holding no communication with the city.

“The first, therefore, in the ceremonial, were the Greeks. Entering from their convent by the grand entrance, they walked three times round the rotunda inclosing the Holy Sepulchre, chaunting the service, and each bearing a palm-branch. Their banners and dresses were splendid. Their two bishops wearing circular caps and sumptuous robes, were supported each by two dignitaries wearing similar robes, crimson velvet embroidered with gold. At the head of the procession was carried a representation of Christ on the Cross, which the pilgrims pressed forward to kiss. On entering the chapel, the chief bishop, ascending the steps to the central opening of the screen, gave his benediction to the multitude, holy water was sprinkled, and flowers were strewed on the steps leading to the Holy Sepulchre. The two bishops then seating themselves on gilded thrones on either side of the chapel, distributed baskets of consecrated bread.

“Next followed the procession of the Armenians their bishop wearing a mitre and a robe still more glittering than those of the Greeks, being covered with pearls and precious stones on a ground of crimson velvet. The Copts and Syrians joined this procession, being too few to form a separate one. The Copts carried a representation of Christ on the Cross and banners. But their appearance was poor, and their bishop bore but a staff of ivory, while those of the Greeks and Armenians were of chased gold set with gems.”

The point of time in the engraving is when the Armenian bishop has taken his place in front of the altar.

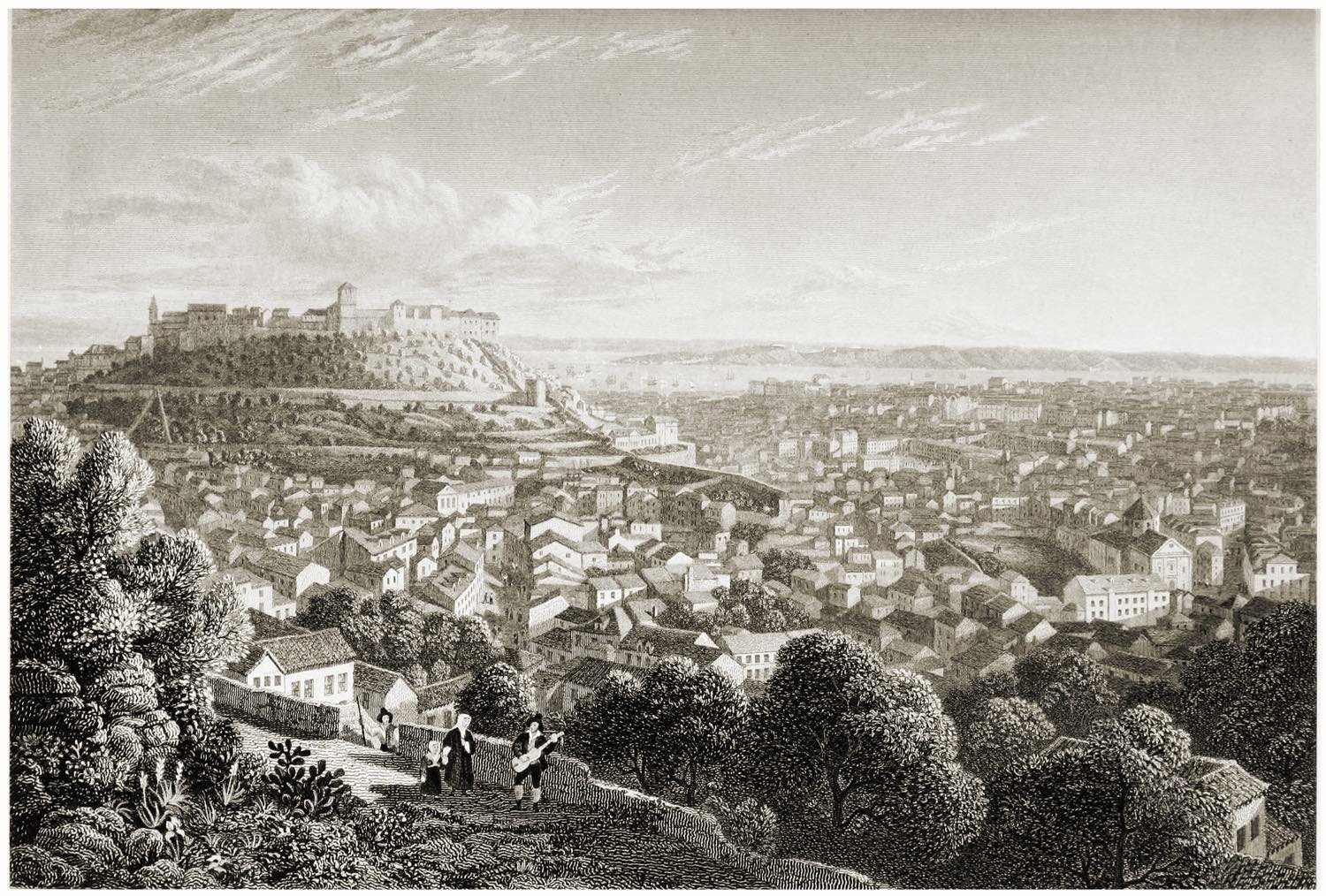

THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY SEPULCHRE.

THE artist has sketched for us the present appearance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. Directly across the street from this amorphous structure is a hotel; Mr. Cornwell’s rooms faced the church front, so that we in regarding this picture are seeing what the artist saw from his lodgings every day.

In Palestine, when a building is erected, it does not occur to anyone to take away ruins and rubbish that may surround it. As the tree falls, so shall it lie. Thus new and old touch elbows; everywhere in Palestine the incongruous is the normal. The main portion of this church is almost a part of the ruins that hedge it in. At the extreme upper left, you see an arch that has broken down, like the bridge at Avignon. It was not left, however, for any romantic or sentimental reason, but simply because the builders did not take the trouble to remove it, and no one else seems to have felt the necessity of doing so. Such is the prevailing custom in that untidy land.

The space in front of the church is as animated as the Piazza of St. Mark’s in Venice. Mr. Cornwell says that the scene he has reproduced is typical; every day that he was in Jerusalem it looked just about like this. Religious processions, social gatherings, sordid barter, general gossip all find a place here; in the left foreground one sees a group of dark figures. They are priests of some order, who assemble here daily; to do what? To gamble. Surprised by this spectacle, the artist inquired of a bystander, and he was informed that the priests spent their whole time here rolling dice.

This would perhaps seem more shocking if it did not take us back in history to the greatest of all dramas, here enacted, where the indifferent soldiers gambled for the garments of the King.

Source:

- The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, & Nubia, by David Roberts, George Croly, William Brockedon. London: Lithographed, printed and published by Day & Son, lithographers to the Queen. Cate Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1855.

- The City of the great king and other places in the Holy Land. Pictured by Dean Cornwell and described by William Lyon Phelps. Society of the Four Arts King Library, 1926.

Continuing